Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSMALL IS BEAUTIFUL

TOYS

Thanks to obsessions such as Latrell Sprewell's scalp and Adam Sandler's teeth, Todd McFarlane's adultoriented action figures are more than just plastic replicas of pop-culture stars or characters— they're sort of art! The man who once showed Marvel a few things about comic books has now muscled into a $1.26 billion market alongside Hasbro and Mattel

BRUCE HANDY

Did you know we're living through a golden age for action figures? Don't scoff. I'll give you an example:

The film Little Nicky, a wearying comedy in which Adam Sandler plays the Devil's son, was released in November 2000. Having cost New Line Cinema an estimated $80 million to produce, plus some $35 million more for marketing, the film took in just under $40 million in the U.S.—thus serving neither art nor commerce. But you should see the action figures. They didn't sell much either, but they are genuine pop masterworks, displaying a level of craft that goes way beyond what you'd expect, or even deserve, from a toy retailing for somewhere between $8 and $10 and based on a flop to boot. It's not just that the Sandler dolls actually look like him, although that in itself is an accomplishment given that (a) the faces of these six-or-so-inch figures are not much bigger than George Washington's on a quarter, and (b) part of Sandler's appeal is that he looks like a hundred guys you went to high school with and no one in particular; it's that the attention to detail is so patently neurotic. Each of Sandler's teeny teeth in his teeny gaping mouth has been articulated and given its own micro-dab of paint, as have his little red-brown lips and little pink tongue, not to mention his even tinier black pupils and brown irises. One figure's oversize down coat has been exquisitely sculpted in all its delicate puffiness, a convincing simulation of downy "loft" that, one imagines, is not an easy effect to pull off in the medium of injection-molded polyvinyl chloride.

But the masterpiece of this set of seven figures (collect them all on eBay for around $30; I did) is Mr. Beefy, the movie's talking bulldog. Individual hairs have been carved into Mr. Beefy's coat, a rendering that—combined with a subtle yet elaborate paint job, a series of brownish-tannish-coppery washes approximating the sheen of living dog fur—gives him a feathery, almost hallucinatory effect, similar to a late-stage van Gogh. Better yet, and unlike any van Gogh, Mr. Beefy shoots a barbed, medievallooking missile out of his penis sheath when you lift his leg. It's the sort of feature that adds what the toy industry calls "playability." As the packaging helpfully notes: "Ages 13+."

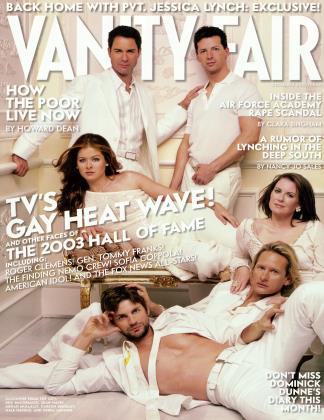

When the action figures are better than the movie, a cultural sea change is taking place. The Little Nicky figures were made by McFarlane Toys, a nine-year-old company that has also produced equally exacting and, in their way, lovely figures based on characters from Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Escape from L.A., Edward Scissorhands, the Matrix trilogy, the first two Austin Powers movies, and the last two Terminators. McFarlane makes figures of our more colorful rock stars, too (Alice Cooper, Ozzy Osbourne, the members of Kiss and Metallica). And then there are the McFarlane Sports Picks figures of professional football, baseball, basketball, and hockey players, not to mention a brandnew series of NASCAR drivers, as well as the occasional oddball one-offs—the Bob and Doug McKenzie action figures, based on the old SCTV characters, or the new "Twisted Land of Oz" set that includes a buxom, corseted, leather-hooded Dorothy held captive by two evil-baby Munchkins, one of whom has just branded her exposed right thigh.

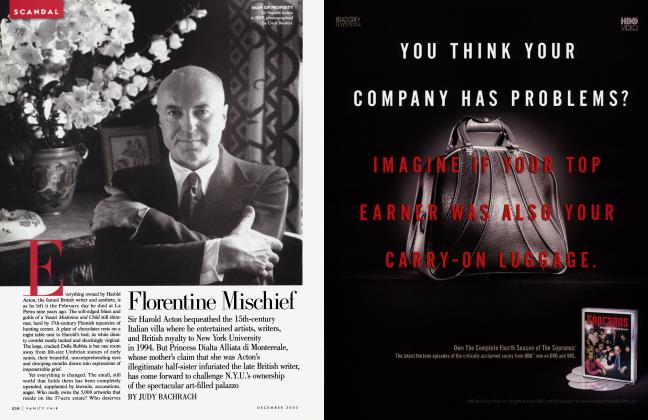

McFarlane Toys is owned by Todd McFarlane, an unusually successful comic-book artist—he brought Spider-Man to record levels of popularity in the early 90s, and subsequently created the Gothic superhero Spawn—who has had even greater success, and perhaps discovered his truest genius, making action figures that will not likely find their way into the sticky hands of actual children. McFarlane, 42, is legendarily hardheaded; as one of his peers says, "He's not a guy who plays well with others." But even people who don't particularly like him will grant that he is as important in his field as Picasso and Charlie Parker were in theirs, and they weren't always easy to get along with, either.

Of course, you always get style points for lavishing production values on an art form most practitioners treat like dreck; that's as true of action figures as it is of pom or Christian rock. But if you speak to people who make it their business to know something about action figures—toy sellers, toy analysts, toy journalists, McFarlane's competitors, guys who work in comicbook stores—they will tell you that McFarlane "revolutionized" action figures, that he "raised the bar" for what an action figure can be, that he "transformed" the way action figures are marketed and sold.

What "raising the bar" for action figures means, I suspect, will not be immediately clear to most readers, but if you are somewhere between the ages of 20 and 40 and think back to the action figures from your own childhood, or your brother's, or the kid's down the street who wore Spock ears and got caught masturbating that time, you will recall homely hunks of plastic sculpted in stiff, dead-person poses, malproportioned, slapped with crude paint jobs. And no matter who they were supposed to be—Rambo, He-Man, Wayne Gretzky, Superman, or Fonzie— they all had the generic features of a male soapopera star: smooth, blandly handsome, inexpressive. At best. When I recently visited McFarlane's main offices in Arizona, Christine Finch, the company's head of licensing, showed me a competitor's Dan Marino figure that looked like it was suffering from acromegaly.

"McFarlane really created the category of upscale figures," says Douglas Goldstein, senior editor of the action-figure magazine ToyFare. "It is no longer acceptable to say, 'Well, this is a toy of the character.' Now fans insist on as good a representation as possible." Or, as Chris Byrne, the editor of Toy Report, a weekly trade publication, puts it: "The sculpting McFarlane has done, the detail in the Figures—if you put one of his figures against a Star Wars figure from the 70s, the Star Wars figure looks like a lump of plastic." This is not said lightly because, in action-figure circles, vintage Star Wars figures are as close to sacred as lumps of plastic get. "Thank God the other guys did it so wrong that me getting it right is considered genius," says McFarlane himself, whom I interviewed, in part, between bites of a pastrami sub as he sat on the floor of the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport, waiting out a rare fog delay for a flight to Los Angeles, where he was scheduled to make a promotional appearance on Fox Sports Net's The Best Damn Sports Show Period. Aside from insisting that his action figures ought to genuinely look like whoever they're supposed to be, McFarlane's real stroke of genius, as a toy-maker, was realizing that there was a profitable niche in making tchotchkes for post-adolescents—viewers of The Best Damn Sports Show Period, say—who would sooner die than be caught buying a Hummel figurine or a Beanie Baby but would still like to share their lives with a six-inch little-buddy version of their favorite quarterback or slasher-movie psycho.

McFARLANE'S COMPETITORS WILL TELL YOU THAT HE "REVOLUTIONIZED" ACTION FIGURES, THAT HE "RAISED THE BAR" FOR WHAT AN ACTION FIGURE CAN BE.

McFarlane explains his business model this way: "It's about creating a toy that, if you had it on your shelf, somebody wouldn't say, 'Are you collecting toys? How old are you? Are you mentally arrested?'" Though there was a small but established adult collectors' market when McFarlane launched his first line of figures, in 1994, he was told again and again that one couldn't design toys strictly with grown-ups in mind. His response: "u can if you (a) pick the right subject matter and (b) make it worthy of a 22-year-old." McFarlane doesn't "do" focus groups, but he understands his brand's "emotional connect," as marketers like to say. Take the 22-year-old, new to the workforce, who graces the top of his cubicle divider at work with a McFarlane Austin Powers or maybe one of the company's darker figures—the Dorothy-as-fetish-object, say, or the mutant Toto, who, aside from his skinless face, looks like a cross between a toad and a triceratops. The toy becomes a symbol, a totem that says, in McFarlane's exegesis, "I am not 50 years old and I am not tired. I don't know the words 'responsibility' and 'adulthood' quite as well as I should. I'm out from Mom and Dad's grasp, much as I love them, but I'm not going to be them."

Hard numbers can be difficult to come by in the fluky, hitdriven toy industry, which is dominated by Mattel and Hasbro, but one informed estimate has adults currently ringing up 30 to 40 percent of all action-figure purchases, a category that, in the reckoning of the Toy Industry Association and the NPD Group (a market-research firm), accounted for $1.26 billion in retail sales last year. (By way of comparison, "plush"—stuffed animals, to laypeople—was good for $1.56 billion.) McFarlane Toys is a privately held company and doesn't release sales figures; most analysts rank it among the top five makers of action figures, and even a smallish slice of that $1.26 billion pie—Sean McGowan, an analyst with Harris Nesbitt Gerard, estimates the company's revenues as being anywhere from $25 million to $125 million, though likely on the lower end of the scale—would be impressive for a company owned by one man with a narrow mandate. "I'm just going to do action figures," McFarlane said when he founded McFarlane Toys. "I'm going to be the king of Aisle 7."

"IT'S ABOUT CREATING A TOY THAT, IF YOU HAD IT ON YOUR SHELF, SOMEBODY WOULDN'T SAY, 'HOW OLD ARE YOU? ARE YOU MENTALLY ARRESTED?"'

McFarlane himself, though he is a superb draftsman and sometimes does concept sketches, is not a sculptor or designer of his company's action figures. His role at McFarlane Toys is akin to what Walt Disney's was at his own eponymous company: businessman, idea generator, impresario, nose for talent—the "creative force," as his press releases invariably put it.

The toys themselves are designed in northern New Jersey, in a cluster of buildings, including a former V.FW. hall and an ex-jail, that are littered with plasticine torsos, arms, heads, and legs from various monsters, movie stars, and ballplayers. The sculptors, most of whom are young men, tend to favor black T-shirts and long, lank hair; a recent visit put me in mind of Gepetto's workshop if Gepetto had been a Slayer fan. McFarlane, meanwhile, works out of nondescript, gray-carpeted corporate offices across the country in a Tempe, Arizona, industrial park. He critiques the sculptors' work (there are typically four sign-off points, sometimes more, in the 9-to-12-month journey from first sketch to Aisle 7 at WalMart) during lengthy phone calls and videoconferences.

Like most creative forces McFarlane is a taskmaster. "There would be times where Todd would be talking about a specific detail on a figure, and I hesitate to say 'harp on it,' but he would just go over and oyer one detail for 15 or 20 minutes," says H. Eric Mayse, a former McFarlane sculptor who is known professionally as Comboy. "One minuscule detail. But to him it mattered that much—he was that into it." (Mayse left McFarlane four years ago along with three colleagues to set up their own shop. Calling themselves the Four Horsemen, they are renowned in action-figure circles for having revived and upgraded Mattel's junky old Masters of the Universe toy line.)

In Arizona, I sat in on a conference call as McFarlane and a colleague in New Jersey went over some test figures that had been sent from one of the factories in China that mass-produce McFarlane's toys. (Thanks to the miracle of cheap overseas labor, McFarlane is able to keep the retail cost of most of his toys between $10 and $15.) The test figures were mostly from upcoming lines of N.B.A. and Major League Baseball stars, with a couple of movie characters thrown in. Over the course of 30 minutes and 18 figures, McFarlane brought up the following:

• Latrell Sprewell's scalp. Could it use an extra coat of paint, the better to set off his comrows?

• The whites of Kobe Bryant's eyes. Were they too small?

• Shaquille O'Neal's skin tone. Was it too dark?

• Baron Davis's lower lip. Had the paint job rendered it too big? ("He looks a little bit like one of the Fat Albert kids," McFarlane noted.)

• The skull plate of the alien from an Aliens and Predator set. It had been given a lacquery paint job to simulate the movie character's sliminess, but had it turned out too shiny and "toy-like"?

"Not that we're making toys," McFarlane added.

What really had him "twitched," as he put it, was the beard on Ichiro, the Seattle Mariners' usually sumameless right fielder. Through a painstaking combination of sculpting and paint applications the company's craftspeople had managed to capture the "subtlety" of Ichiro's scraggly facial hair, but McFarlane was concerned that the rendering's precision would be lost in manufacturing and asked that it be doublechecked weekly during the production process. Later, when I asked what the big deal was, McFarlane launched into a long soliloquy on action figures, facial hair, and the quest for realism that was almost heroic in its obsessive-compulsiveness. "If you were paying attention, you noticed a lot of my comments at this stage are about the face," McFarlane began, "because if you can sell the face the rest of it will go with you. But when you get a face that's only a half an inch tall, the slightest brush stroke changes the look of somebody. It's not only getting the likeness. With Ichiro, the toughest thing is that he, like a lot of Asian men, can't quite grow a beard. So he has this potty sort of mustache, beard, sideburns—it sort of goes in and out. What he has is a bad three-day-growth thing. And if you don't get it right, if it looks like the thickness of his mustache is the same as his sideburns, then it's not him. So what I was seeing on the test figure was they actually painted the hair dark and thick and they were actually getting the subtlety of it. What we do is we actually take little needles and we put little specking in there. We used to sort of try and carve beards. But as soon as they paint it, it looks clunky, too heavy. Facial hair, you can see through it— how do you get a subtlety to it? It can't match the hair on your head because the hair on your head is long hair ..."

He went on for a while longer, and I've edited what's here, but you get the point.

Infortunately, the dream of perfect verisimilitude is often disturbed by the subjects themselves. "Basketball guys are a pain," McFarlane says, "because sometimes they're adding tattoos even as you're manufacturing them. You're like, 'Allen Iverson, you've got to stop! We're two behind already.'" And then there is the occasionally delicate matter of getting celebrities to sign off on their own likenesses. "How many people actually see themselves the way that everybody else sees them? Sometimes the ladies see themselves a little more voluptuous and the guys who have a hook nose don't see that. The problem sometimes is that you actually get it too accurate." According to a McFarlane employee, Johnny Depp, moonfaced by movie-star standards, requested that the face of one of his movie figures be narrowed. Sharon Osbourne, who was handling the sign-offs for McFarlane's 1999 Ozzy Osbourne figure, insisted that her husband's body be sculpted more and more buffly to the point that the finished figure had a near-steroidal physique. Jerry Garcia's widow, Deborah Garcia, accomplished a similar feat for the late, famously pillowy guitarist, who was McFarlane-ized in 2001.

Anyway, as Rodin could have also told you, an accurate likeness will get you only so far. There are issues of pose and gesture and import—of art, for lack of a better word. McFarlane was off on another riff: "Too many companies accept that their toy is what it is by a checklist. Superman—does he have black hair? Uh-huh. Has he got a red cape? Does he have blue long johns? Does he have an S on his chest? Yep. You put all that stuff on there, it's Superman. I don't believe that to be true. Beyond all that, Superman to me needs to look like a king. He needs to be regal. If Superman ever walked into a room in his costume, it would feel like King Arthur walking up to the Round Table—I mean, you go, 'That's the leader.' If you just make this vanilla-looking man in a vanilla stance, and then you put the red cape on, the costume's right, but I don't think the attitude and body language and the dynamics are who Superman actually is. You've got to sort of capture the essence of these people, too."

At this point, we've moved pretty far afield from traditional definitions of playthings, which begs the philosophical question: what exactly is an action figure? A posable piece of plastic would be the reductive answer. But the action figure is best defined by what it is not, and what it is not, everyone in the business will tell you, is a doll. Dolls are girl toys—even when they are trained killing machines, which was the dilemma Hasbro faced in 1963 when it invented G.I. Joe, who, despite the literally trademarked scar on his right cheek, was essentially a Barbie for boys. (Like Barbie, Joe was expected to generate most of his revenue through the sale of accessories.) Faced with having to call their new toy something, G.I. Joe's makers coined the term "action figure." Language is control, as Orwell knew, and having thus convinced boys there was nothing femmy afoot, Hasbro introduced Joe to the marketplace in 1964; within three years he was the best-selling toy among 5to 12-year-olds, almost singlehandedly establishing new "play patterns" for boys, who now had a rugged, pint-size friend they could unembarrassingly bond with and carry around the neighborhood. (In 1989, a U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that, for purposes of calculating import tariffs, Joe really was a doll, but don't tell Mikey and Scooter.)

Action figures based on characters from TV shows and movies had become popular by the 1970s (the toy company Mego licensed everything from no-brainer properties such as Planet of the Apes and Starsky and Hutch to the less obviously "toyetic" Sonny and Cher). But the release of Star Wars in May 1977 transformed the action-figure business nearly as radically as it did Hollywood. When Kenner wasn't able to get its Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia figures into stores in time for Christmas that yearmovies weren't milked as quickly and ruthlessly then as they are today—the company instead manufactured empty packages with I.O.U. certificates promising delivery of the actual toys by spring. Despite the well-known buy-me-it-now focus of young consumers, Kenner still managed to move hundreds of thousands of I.O.U.'s, selling out in many stores.

"BASKETBALL GUYS ARE A PAIN BECAUSE THEY'RE ADDING TATTOOS EVEN AS YOU'RE MANUFACTURING THEM. YOU'RE LIKE, 'ALLEN IVERSON, YOU'VE GOT TO STOP!'"

It wasn't just the desirability that comes with any hit; the movie's fanciful, vividly designed characters lent themselves to action figures in a way that earlier blockbusters hadn't. As Douglas Goldstein, the ToyFare senior editor, points out, "Over the past three or four decades, entertainment has become a lot flashier, which has lent itself to people desiring product. Star Wars or even a Battlestar Galactica were so colorful, with such colorful characters, that the toys became special, whereas, before the age of special effects, entertainment was basically just people. When kids were watching all the cowboy-and-indian shows in the 50s, they were watching people. Once you have a couple cowboy toys, do you need another licensed one?" But what about James Bond, the character who launched the first modern movie franchise and was turned into a doll after Thunderball came out in 1965? Why didn't that take off? "James Bond is just a guy in a suit," says Goldstein. That is not a good thing in action-figure terms. Indeed, McFarlane offers a similar critique when explaining why he declined to bid on the license to make action figures for the most recent 007 movie: "Bond's not sexy enough to me. A guy in a three-piece suit? How many poses can you put him in? I just can't wrap my head around it."

McFarlane does have a life. He is married to his high-school sweetheart (though born in Calgary he spent most of his childhood in Southern California), and the couple has three children, two girls, 12 and 9, and a boy, 4. He is also a Renaissance man of sorts. Aside from making action figures and publishing comic books (he still inks the covers for Spawn), he has produced a Spawn movie (released by New Line Cinema in 1997 to poor reviews and decent box office) and an animated Spawn series for HBO (for which he won an Emmy). He also directs music videos (he won a Grammy for Korn's "Freak on a Leash"), and currently hosts an Internet radio show for Major League Baseball. He is a minority owner (reportedly 2 percent) of the N.H.L.'s Edmonton Oilers and is probably most famous, among people who don't go to comic-book conventions or wait in line at Toys 'R' Us to get their N.F.L. action figures signed, for having paid $3.2 million at auction for the baseball Mark McGwire hit for his then record 70th home run in 1998. The fact that "The Ball," as everyone in McFarlane's employ refers to it, may have lost some if not most of its value when Barry Bonds hit 73 homers in 2001 doesn't seem to faze him; as he cheerfully points out, by offering the winning bid he had, by definition, already paid more than anyone else thought it was worth. This truism presumably still held last June when he bought Bonds's recordbreaking ball for a comparatively rational $450,000.

McFarlane radiates the easy swagger and the self-deprecatingbut-not-really humor of someone whose cocksureness has largely been rewarded in life; if you can picture George W. Bush in tight jeans, black loafers, a blue ribbed T-shirt, and a silver chain necklace—and you may not want to—you will have some sense of McFarlane as a presence. He still has the wiry body and coiled energy of the aspiring major-league outfielder he had been when he broke his ankle sliding into home while on a baseball scholarship at Eastern Washington University (necessitating a career change to comics, his second love). He talks fast, and when he gets worked up—about the greediness of lawyers, say, or the imbecility of making hockey action figures with their jerseys tucked in, the way Hasbro used to ("Do hockey players tuck in their jerseys? No. Not in a million years!")—his face hardens and he starts to look like the sort of beady-eyed, back-alley thug Spider-Man would make short work of.

Back when he was drawing that character for Marvel Comics in the 80s and early 90s, McFarlane was the highestpaid artist in the industry, making nearly $2 million a year in a profession noted for generating more bitterness than wealth. His calling card was his bold and spectacularly detailed drawing style, which is echoed in the action figures. He gave Spider-Man a new physical dynamism, along with bigger, buglike eyes, but became especially famous among fans for his take on the character's webbing: not only did he render every strand, but he gave it a knotty, fluid, more biological look. (Some might describe it as "spoogey.") Under McFarlane, The Amazing Spider-Man became the industry's best-selling title. In 1991, when this was still an unambiguous tribute, People magazine described him as "the comic-book equivalent of a Robert Redford or a Madonna."

But McFarlane wanted to own the rights to his own material. When colleagues heard he was leaving Marvel they assumed he was going to DC, the only other major player in the business. Instead, he and six other disaffected Marvel artists started their own publishing corporation, Image Comics. (A sports-world equivalent would be Derek Jeter and Jason Giambi leaving the Yankees not for the Red Sox or A's but to form their own team, and in a place like Albany.) McFarlane began publishing Spawn in 1992. The title character, whom McFarlane had conceived back when he was in high school, is a supersecret government assassin who, having been killed by his superiors, goes to hell, but is then sent back to earth as a kind of advance man for the forces of darkness; he's not really a bad guy—he only agrees to help out hell so he can see his wife again. (Still following?) McFarlane loyalists snapped up 1.7 million copies of the first issue, a record for an independent comic. The selling point, aside from McFarlane's hyper-detailed, almost hallucinatory art, was a ponderous tone that took the adolescent mopiness of the average contemporary superherocheerful crime fighters pretty much died out in the 60s—and inflated it to epic proportions; what The Odyssey is to sailboat trips, Spawn is to brooding.

Its success nudged McFarlane into toy-making. With six or so issues under his belt, he was being approached by all kinds of manufacturers looking to license Spawn. "They all thought it would be good for pajamas and Colorforms and coloring books and all this silly stuff—without reading the book. I could always tell. I'd go, 'You're from a coloring-book company? Have you read this book? The guy's from the pit of hell.' They'd go, 'Oh.'" Needless to say, the coloring-book and pajama representatives didn't call back. Action figures were a more obvious fit, however, and toy-makers more persistent suitors, but, as McFarlane puts it, "They were just going to sell Spawn the exact same way they sold their Sesame Street toys." Unimpressed as well with the financial terms he was being offered, McFarlane looked into the feasibility of making his own Spawn figures by calling on a few connections he had in toys and manufacturing (including a minority partner whom McFarlane later bought out). "We all kind of laughed," says Terry Fitzgerald, who started out filling in the backgrounds on McFarlane's comics and now oversees McFarlane's movie, music, video-game, and TV interests. "First Todd is crazy enough to start a comic-book company and take on million-dollar companies like DC and Marvel. And then he's stupid enough to start a toy company and take on billion-dollar companies like Hasbro and Mattel."

"JAMES BOND'S NOT SEXY ENOUGH TO ME. A GUY IN A THREE-PIECE SUIT? HOW MANY POSES CAN YOU PUT HIM IN? I JUST CAN'T WRAP MY HEAD AROUND IT."

"If you're going to try and go up against the giants, you've got to find something that they can't do," says McFarlane. "They were trying to maximize their profits and, I thought, trying to cheat the customer. So I go, 'What they won't do is spend the extra 5 cents, 10 cents, 12 cents, here, here, and here. It's not that they can't build the mousetrap any better than me—it's that they're only spending 60 cents. So if I spend a buck, I should be able to build a better mousetrap.'" Within a few months of deciding to get into the business, he was showing off prototype figures at Toy Fair, the industry's annual trade show in New York. At that time, it was far from certain whether the toys would actually be manufactured; one key was generating advance orders. As McFarlane remembers his first Toy Fair, "We were in this showroom that had 20 guys like me, all sort of hawking their stuff, where somebody like Hasbro had a whole floor. We were like one office divided by 20. The buyer from Toys 'R' Us came in. There was a hush. It was like Moses was coming into the room. He walked through and everybody's like, 'Pick me! Pick me/'" According to Fitzgerald, the buyer "turned out to be a Spawn fan, knew all the comics. He said, 'I'll give you a small order. If I sell it, great. If not, well... ' He knew full well that toys might not even see the light of day, so what did he care?" But it was the Toys 'R' Us order that gave what was then called Todd Toys credibility and got the company off the ground. That first Spawn line remains one of its all-time best-sellers.

"IT'S NOT LIKE I'M TRYING TO SELL TO MOM HERE. IF I WANTED THIS TO APPEAL TO 47-YEAR-OLD MOTHERS, I WOULD HAVE GIVEN THEM LUCILLE BALL TOYS."

In 1997, McFarlane Toys launched its first series of non-comicbook (though still cartoonish) figures: the four members of Kiss. Jocks—now one of the company's biggest revenue producers— were a harder category to crack. "Todd is a big sports fan, so all we talked about was how we could get into that business," says Ed Frank, McFarlane's chief designer. "It's Catch-22 when you try to get a sports license, and that is they want to see what you did before. It's like, 'How can I show you what I did before when I don't have the license to do it?' But we said, 'You know what? There are sports movies.'' And Slap Shot was our favorite. We loved it." Producing a set of figures based on the Hanson brothers, the trio of Coke-bottle-lensed hockey goons from the 1977 Paul Newman comedy, may not have made a ton of sense microeconomically but it got McFarlane's foot in the door. Buying the McGwire ball helped too, at least as an icebreaker in meetings with sports executives.

McFarlane has taken a couple of stabs at making toys for actual children. There was a series of figures based on Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are, and McFarlane landed the license to Shrek after Hasbro passed. Neither line met sales expectations. "The 10-and-under crowd isn't looking for high-detailed, beautiful 'sculpt' toys. They want stuff to squeeze," says Chris Byrne, the toy analyst. The move into sports figures has helped McFarlane become more "Mom friendly" in the eyes of big retailers such as Wal-Mart and Target, which is arguably a good thing since some of the company's toys are expressly not. Two hot-selling lines of figures called Tortured Souls feature pierced and flayed victims designed in collaboration with the horror and fantasy novelist Clive Barker. They look like something Josef Mengele might have dreamed up in a more playful moment; if the description sounds offensive, that's sort of the point. "It's not like I'm trying to sell to Mom here," McFarlane says. "If I wanted this to appeal to 47-year-old mothers, I would have hit that target dead in the eye. I would have given them Lucille Ball toys." Instead, he's "looking for that 27-year-old who goes, 'Oh God—his chest is opened up. Cool, man!' It's the same reason you go to horror films, you know? It doesn't mean you're going to walk out and disembowel somebody. It's just stuff to look at."

This is a phrase, "It's just stuff," that McFarlane uses repeatedly, seemingly to deflect anyone trying to attach too much importance to what he does. He's not one for selfanalysis, but he obviously cares deeply about his creations. According to ICV2.com, a Web site devoted in part to comic-book news, he became visibly emotional last year while testifying during a trial in which he was being sued over the rights to some Spawn spin-off characters that had been created by another writer: "McFarlane was so upset ... that it appeared he might break down, but he was able to compose himself after taking a drink of water and remaining silent for a time. It was obvious that he has great love for his most important creation, and that it was the prospect of losing control of even a small piece of it that was most upsetting to him." (McFarlane indeed lost the suit, but is appealing.)

To my eye, McFarlane's figures still stand out on a toy-store shelf, but his competitors are gaining. Smaller firms such as Palisades Toys, Art Asylum, Playmates, and Mezco have been turning out impressive figures, and even lumbering Hasbro has gotten nice reviews for its recent Star Wars figures—a 12-inch Jango Fett won ToyFare's Toy of the Year for 2002—although one typically pedantic McFarlane employee I interviewed couldn't help pointing out that a Padme Amidala figure from Attack of the Clones has fewer gashes on her back than did Natalie Portman. Meanwhile, with the adult collector market burgeoning, the fight for new licenses has grown so fierce that even characters from barely remembered movies such as Big Touble in Little China, Legend, and Judge Dredd have become toys. You can also buy action figures of Jenna Jameson, Ted Bundy, George W. Bush, and Toshiro Mifune, to name four individuals of random accomplishment. And perhaps this was all inevitable in a society in which adulthood is deferred until the age of 35 or so.

I used to think that there was something pathetic about a toy that isn't played with, but I've learned that's a sentimental notion out of Toy Story. A couple of months after I listened to McFarlane obsess over Ichiro's facial hair, I strolled into a toy store and found the finished figure on sale. I was amused and surprised— and pleased—to see that his beard and mustache had survived the manufacturing process with all due pottiness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now