Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFrom the roughest of Brooklyn’s Jewish ghettos came one of the smoothest comics of all time: Phil Silvers, loved and laughed at by pals such as Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, and Bing Crosby. Eighteen years after Silvers’s death, his Sergeant Bilko TV series still crackles with a proto-Seinfeldian wit

April 2003 David KampFrom the roughest of Brooklyn’s Jewish ghettos came one of the smoothest comics of all time: Phil Silvers, loved and laughed at by pals such as Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, and Bing Crosby. Eighteen years after Silvers’s death, his Sergeant Bilko TV series still crackles with a proto-Seinfeldian wit

April 2003 David KampThe more time you spend in the company of comedy’s senior citizenry, that august fraternal Jewish order with chapters in Manhattan, Beverly Hills, Boca Raton, Las Vegas, and the Actors’ Fund Nursing Home in Englewood, New Jersey, the more accustomed you become to hearing this boast: “Me, I was the only one who could bust Sinatra’s chops. The others, they were all terrified of him, wouldn’t say nothing to him. But I gave him shit all the time. And you know what? Frank loved it.” Frank, conveniently, is unavailable to confirm or refute this claim, which lends the whole exercise a certain dubiousness, an unseemly air of grasping for immortality-by-proxy. But Phil Silvers, a true immortal, never had to stoop to such depths—he busted Sinatra’s chops and thought nothing of it. And Frank did love it. On U.S.O. tours, at private parties, at Hollywood events, they’d go into an old burlesque routine, called “The Singing Lesson,” in which Silvers dressed down Sinatra for his shabby technique—slapping the singer’s cheeks, molding his mouth, holding in his stomach, exasperatingly imploring, “No, no, no, no, no, no! From the diaphragm. From the DYEa-FRAY-um!, ” until, finally, Sinatra produced a squawk so strangulatedly atonal that Silvers had him convinced he couldn’t sing at all.

It was a rare talent who could carry off a bit in which he was the sharpie and Sinatra the patsy, and an even rarer talent who could do this while looking, as Silvers did, like an accountant: black horn-rimmed glasses, pillowy, feminine features, and a huge, hairless cranium that protruded from the lower half of his head like a soft-boiled egg from its cup. But Silvers had a con man’s suavity and cheek that belied his Poindexter appearance. His unctuously delivered catchphrase, “Glad to see ya!”—which is better represented in print as “Gladda-seeyaaa!,” gliding along rivulets of WD-40—was a stall tactic, his way of taking a moment to size up the person he was allegedly glad to see and figuring out which angle to work. In real life, Silvers’s gift for ingratiating patter enabled him to engage figures who, like Sinatra, scared the hell out of most people: the Murder Inc. gangsters who controlled his childhood turf in Brownsville, Brooklyn, the screamers who ran the Hollywood studios, the boxers whose fights he attended religiously. In performance, Silvers put his slickness to use in the service of a variety of brilliant, fast-talking schemers, the most famous and enduring of whom is Master Sergeant Ernest G. Bilko, the protagonist of his hit 1950s TV series, The Phil Silvers Show, later known simply as Sergeant Bilko in syndication.

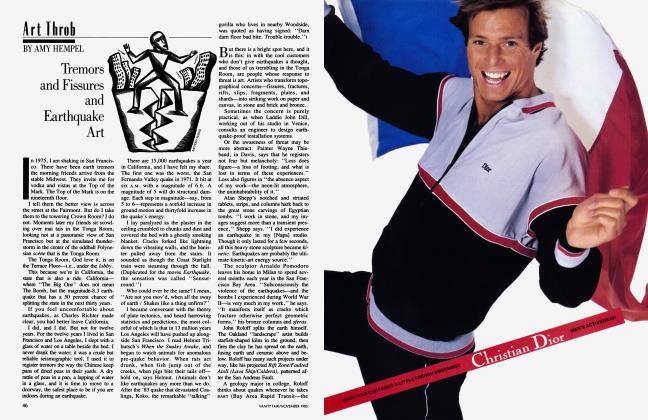

"There was something fluid, liquid, flowing about himwicked, yet wonderfully sott, remembers Dick Cavett

Ernie Bilko is one of the great comic personae to have been concocted in the 20th century, up there with Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp and Julius Marx’s Groucho. “It’s impossible to describe Silvers’s style to someone who hasn’t seen him, because he was just not like any other comic. There was something fluid, liquid, flowing about him—wicked, yet wonderfully soft,” says Dick Cavett, who landed a bit role in a Bilko episode in his aspiring-actor days and later interviewed Silvers on his PBS talk show. Though Bilko was nominally in charge of the maintenance of the motor pool at the mythical Fort Baxter in Roseville, Kansas, he occupied himself and his platoon with poker games, get-rich-quick schemes, and elaborate plots to bilk the army bureaucracy out of all the perks and unearned entitlements he could get. (The show’s sports-mad creator, Nat Hiken, lifted the character’s name from a major-league ballplayer, Steve Bilko, because he liked the resonance.) The Phil Silvers Show was fast and grubby, with flubbed lines kept in as long as the feel of the scene was right, and a supporting cast so comically rough-looking that you’d swear the show’s producers had gone trawling through betting parlors and boxing gyms—which, as it happens, is pretty close to the truth. Silvers played Bilko as a charming, benign duke of deception, addicted more to luxury than criminality—he wore silk Chinese pajamas in the comfort of his own barracks and magnanimously treated his two deputies, Corporals Henshaw and Barbella, like trusted concieiges in his personal Ritz-Carlton. His chief dupe, Colonel Hall (played by the jelly-jowled Paul Ford, the Margaret Dumont to Silvers’s Groucho), was a sympathetic foil rather than a villain, and the multi-ethnic collection of ugly mugs in the platoon were Bilko’s adoring acolytes, agog at his chicaning genius; in every episode, there’s at least one scene in which they’re all arrayed around Bilko in a halo, like the apostles in a Caravaggio, their heads cocked eagerly to hear the Sarge’s latest poyels of wizdum.

As any aficionado knows, there are few experiences as uncomplicatedly pleasurable as taking in a vintage Bilko episode and watching Silvers tie himself up in situational knots. “It is like going back to a good book—you dip into the old shows, and they are absolutely impeccable,” says the English director and playwright Mike Leigh, who pronounces himself “an unreconstituted Bilko groupie.” His favorite episode, “Doberman’s Sister,” is a worthy example. Family visiting day is approaching at the barracks, and each of the men must commit to a date with a fellow G.I.’s sister for the big dance, and no one wants to pair off with the sister of the platoon’s ugliest member, Duane Doberman. Bilko solves this problem by devising, on the spot, a bit of pseudoscience called Musselman’s Law and Theory of Family Equalization: “Musselman was a scientist. He devoted his life to this research. And he came up with the simple statement, which I’ll tell you in simple, basic English: the uglier the brother, the more beautiful the sister.” Naturally, the men are left panting at the prospect of dating Doberman’s sister, leading to a wonderful series of dream sequences in which Doberman presents various bullet-bra’d knockouts as his kin. As the anticipation builds to a fever pitch, Bilko himself begins to believe in Musselman’s Law, and ditches his own beautiful date in order to hustle off to the bus station to intercept Doberman’s sister—who turns out to be Maurice Gosfield, the troglodytic actor who played Doberman, in drag.

In just four years, from 1955 to ’59, Silvers and his co-conspirators produced an astounding 144 episodes of the Bilko show, all shot in New York and all suffused with a streetwise, writtenin-Lindy’s zip that vanished from situation comedy when television’s operations moved west. Not that you’d know any of this from turning on your set today. Curiously, The Phil Silvers Show is overlooked by the classic-TV industry that keeps I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners perpetually in the public consciousness, familiar even to Nintendo kids; the last time the Silvers show aired nationally was in 1998 on the TV Land cable channel, which has no current plans to bring the show back. This lack of attention is all the more regrettable because the program has dated the least of the black-and-white 50s warhorses. With its nakedly self-interested protagonist and its spring-loaded plotlines, which always build up to a finish in which Bilko’s scheme du jour explodes in his face like a trick cigar, The Phil Silvers Show is a clear antecedent to Seinfeld and Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm, the hippest and most formula-forward TV comedies of recent years. “Phil was just a sharpshooter—very, very hip,” says Red Buttons, whose friendship with Silvers dated all the way back to their days working in burlesque in the late 1930s. “Bing Crosby was the hippest of the singers, and Phil, I think, was the hippest of the comedians. He was today and tomorrow, not yesterday.”

Buttons theorizes that Silvers’s posthumous profile has suffered for the fact that he never got to take a post-career victory lap. He died in 1985 at the age of 74, just when most of his contemporaries were entering that period when, by simple virtue of their longevity, they’d receive compulsory standing O’s just for tottering out onstage at awards shows. “He just wasn’t around long enough,” Buttons says. “If Phil had been able to catch another 20 years in the business, which most of the guys seem to be doing—Milton Berle, 93; Henny Youngman, 91; George Bums, a big number—he would have been royalty.”

As it is, Silvers enjoys his most exalted status in Great Britain, of all places, where the BBC has never stopped airing the Bilko show since the program had its British premiere in 1957. (He’s also the only American actor to have appeared in a major role in one of the Carry On slapstick comedies that were filmed in England in the 1960s; he played—what else?—an army sergeant in Carry On up the Legion.) “Over here, Bilko is perceived as the Rolls-Royce of American TV comedy,” says the author Mark Lewisohn, who, though better known as the world’s foremost Beatles expert, is also a television historian who was tapped to select episodes and write the liner notes for The Phil Silvers Show’s U.K. release on video. “Everyone I know who loves Bilko loves it for its sheer speed,” he says. “Maybe that’s something the British respond to.” Kenneth Tynan, Britain’s dean of provocateur critics, certainly did, warmly describing Silvers in his diaries as a “matchless, whiplash clown” and regretting that he never devoted an essay to the great comic. Leigh allows that his own good-humored verite sensibility, as witnessed in his blobby-bodied cuppa-tea dramas Secrets and Lies and All or Nothing, owes at least a little to his lifelong Bilko habit. “It is one of the things that has shaped me,” he says. “Taking characters that people recognize, not generalizations or caricatures, and placing them in heightened but plausible situations.”

It was another British fan, a woman, who unwittingly gave Silvers his last significant worldwide exposure, two years after his death. The woman, visiting Tibet as a tourist, was roughed up outside of Lhasa by a Chinese soldier who mistook the bald, bespectacled figure on her T-shirt—Silvers as Bilko—for the exiled Dalai Lama. As the soldier sought to arrest the woman for her flagrant act of political provocation, a group of Tibetan bystanders gathered around, sympathetic to the woman but no less confused; pointing excitedly at her shirt, they chanted, “Dalai Lama! Dalai Lama!” Well, Silvers was transcendent.

T he Phil Silvers Show was the culmination of a show-business career that took years to lift off into the big time. Silvers started out as a boy singer in Brooklyn movie houses, belting out flapper-era novelty hits like “Big Boy” (“They all say that since he kissed old widder Johnson / Now she thinks she’s Gloria Swanson!”) whenever the projector broke down. At one of his first proper paying engagements, a beer-hall party in honor of a justsprung Murder Inc. enforcer named Little Doggie, two hoodlums stormed in and carried out a hit on a third; the victim fell dead at Silvers’s feet as he sang. He was eight at the time.

Silvers’s parents had come to New York from Russia, where they’d been on the run from the Cossacks, evidently because his father, Saul, had brained a soldier with a shovel for making a move toward his wife, Sarah. Phil, Fischl to his parents, was the eighth and last of Saul and Sarah’s children to be born, in 1911, by which time the family had relocated from the tenements of Manhattan’s Lower East Side to Brownsville, the roughest of Brooklyn’s Jewish ghettos. (Silvers’s real surname was Silver, minus the final s, and not Silversmith, as is stated in most reference guides. The mistake probably arises from the fact that his father had worked as a tinsmith.) In Brownsville, Silvers’s local heroes were gangsters like the Amberg boys, Pretty Boy and Hymie, and Benny Siegel, better known as Bugsy, with whom he later became friends on the West Coast. Though his own criminal activities never advanced beyond the juvenile petty thievery endemic to Brownsville, Silvers always retained a certain groupie-ish admiration for Jewish tough guys. “What was my attraction to Bugsy Siegel?” he said to Dick Cavett in 1981. “I was so sick of the nonmilitant Jew. No one came into my neighborhood and said ‘Jew bastard’ and walked away.” Despite his outward appearance, Silvers spent his entire life exulting in rough, sweaty, manly-man milieus, compulsively attending prizefights, baseball games, and horse races, and betting on anything someone would take a wager on. And though he wore the horn-rimmed glasses from his teen years onward, he never once played a nebbish.

"He wasn't on the make," recalls Jo-Carroll Dennison. "He made me laugh, and didn’t try to get me into bed.

With the arrival of puberty, the pleasant timbre of Silvers’s singing voice vanished, and he assumed he was finished in show business. But Joe Morris, a fading vaudeville star who had heard Silvers sing, tapped him to appear in his latest show, Any Apartment. The show was, bizarrely, a comic autobiographical playlet that starred and concerned Morris and his ex-wife, Flo Campbell, former headliners whose marriage and act fell apart when, at the peak of their fame, Morris fathered a child out of wedlock. From age 14 to 20, Silvers, wearing short pants, played Morris’s illegitimate son, touring Any Apartment endlessly around the Northeast vaudeville circuit. But by 1931, vaudeville was on its last legs, Flo Campbell was going deaf and hurting the act, and Silvers was almost six feet tall and no longer able to abide the shorts. He quit the act, realizing too late that it was the height of the Great Depression and that there weren’t any acting jobs out there that paid the kind of money he’d been making with Morris and Campbell.

About the only steady work to be had was in burlesque, the low-comedy revue format that, in the grips of the Depression, had become increasingly reliant on strippers to draw in customers. For Silvers, it was a comedown from vaudeville, but, as he related in his memoir, This Laugh Is on Me, “burlesque gave me a lot of freedom. I could improvise anything I wished— a new bit here, a couple of lines there didn’t matter to others in the scene, as long as it all got us to the blackout.” In burlesque, there was no new material per se, only new variations on a finite number of hoary sketches that had been passed down from one generation of comics to the next, seemingly since the time of Plautus. Two comics who had never before worked together could simply rattle off some sketch titles—“Pullman Scene,” “Sam, u Made the Pants Too Long,” “Fireman, Save My Wife”—and instantly conjure an act to put onstage. (Some burlesque comics were actually known by the names of their trademark sketches, e.g., Harry “Hello, Jake” Fields and Peanuts “What the Hay” Bone.) Silvers knew he was better than this material, but he also knew that it could be a means to a better end, as it had been for Eddie Cantor, Bert Lahr, and Abbott and Costello, whose famous “Who’s on First?” routine was actually an old burlesque bit that they’d appropriated as their own.

Silvers found a mentor in Herbie Faye, a bald, hollow-eyed veteran of the strip houses, and a best friend in Rags Ragland, a hard-drinking Kentuckian who’d failed as a boxer and decided to give comedy a try. From Faye he learned the ropes and etiquettes—never move on someone else’s line; don’t date the strippers, they go with the straight men—and with Ragland he perfected some bits that he would recycle throughout his career, chief among them the “Singing Lesson” sketch he later performed with Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Perry Como, and any other famous crooner he found himself standing opposite. Silvers also forged friendships with Milton Berle, Jackie Gleason, Red Skelton, and Red Buttons, all of whom, like him, were young comics on the make in the 1930s working at the Gaiety, the burlesque palace at 46th and Broadway, and trading jokes about the shabby Times Square flophouses they were living in. How small were the rooms in these joints? One guy put his key in the lock and broke a window. Rim shot! Another guy dropped his toupee on the floor and all of a sudden he had wall-to-wall carpeting. Cymbal crash! Then there was the guy who called the desk clerk and complained, “I gotta leak in my tub!” To which the desk clerk replied, “Go ahead, it’s your tub.” Ba-dum-bump!

In burlesque, the comic sketches functioned essentially as time killers between stripteases. “You opened with a chorus number, followed by a [comic] scene, followed by the first strip, followed by another scene and another strip and so on—about four strips a show, and shows were usually, like, an hour and a half,” says Buttons, one of the last survivors of this gauntlet. Since the all-male audiences weren’t there primarily to laugh, when they did laugh, you knew you had something. Silvers made them laugh more often than most, his youthful hyperactivity offering relief from the tired, vulgar shtick of the fossilized baggypants lifers around him. “Phil was a trailblazer,” says Buttons. “He worked in clean clothes, which was not the norm. The burlesque men generally wore costumey, oversized clothing: big, oversized shoes and such—clown stuff. Or the other way, undersized. It was telltale, like walking out and saying, ‘O.K., I’m a comedian.’ But Phil dressed almost like a straight man.”

As his profile rose, Silvers became a favorite of H. K. Minsky and his nephew Harold, the Shuberts of shtick-and-strip, who owned the Gaiety and several other burlesque houses.

He was also beloved by the strippers, who felt a compulsion to sexually educate the sweet kid with the boyishe punim. Sherry Britton, one of the leading ecdysiasts of this period, says she was never involved with Silvers, but remembers him as “one of the gentlemen of burlesque—he wasn’t crude and rude or cruel. The difficulty about most burlesque people was that they had no self-respect or respect for each other. Phil was different.”

Still, all the romanticizing in the world of burlesque-as-exhilarating-demimonde couldn’t mitigate the fact that it was, at times, a debasing way to make a living. “It was disgusting,” says Britton, “because there was a great deal of masturbation going on, and you couldn’t miss it from the stage. You saw the different styles that these men had—some with hats covering, some with coats, some with newspapers, some naked and spewing their seed on the concrete floor of the theater. And then we’d have to go out later, and we’d slip and slide in all this.” By 1939, Silvers was a burlesque topliner—a first banana, in the vernacular of the trade—but he knew he had to move on. When he was offered a small part in Yokel Boy, a new Broadway musical starring Buddy Ebsen, he jumped at the chance, even though the $150-a-week pay was a comedown from the $275 the Minskys paid him.

Yokel Boy was an unfocused mess of a show that had been concocted by Lew Brown, a well-known songwriter. Ebsen, returning to Broadway after an ignominious stint out West with MGM—he’d been cast as the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz, only to be let go after he had an allergic reaction to the silver makeup-played a hillbilly dancer who is discovered by a famous director. The director role went to Jack Pearl, an old vaudeville trouper whose distinctly antiquated specialty was funny Dutch and German accents. Silvers had a bit role as the director’s assistant. When the show bombed in out-of-town tryouts, Pearl quit. Lew Brown and his writers, sensing the untapped talent they had on hand, hastily reconceived the show around Silvers, discarding the director character and placing Ebsen’s yokel boy in the hands of a brash Hollywood press agent named Punko Parks—a proto-Bilko who was the template, Silvers later said, for the “aggressive, smiling, call-a-tall-man-Shorty manipulator” he would play for the rest of his life. Alas, that description was about as far as the writers got, conceptually, before it was time for Silvers to take the stage in his new role. “He went out on opening night and adlibbed his whole part,” says Ebsen, still hanging in there at age 95. “He was playing Phil Silvers—‘ya, glad to see yak And he kept talking, and you didn’t have to say anything. You just shook your head ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ and he kept talking. And he was a big hit. He hugged me later and said, ‘Thanks for holding still’—which was all I did while he talked his part around me.” Yokel Boy was not a major triumph, but it lingered long enough, about six months, to give Silvers the credibility and visibility he needed. “It established Phil Silvers as somebody,” says Ebsen, “ ’cause no one had ever heard of him, being from burlesque.” Louis B. Mayer caught the show while he was in New York, and was sufficiently impressed to offer Silvers a $550-a-week contract at MGM.

Silvers spent most of the 1940s in Hollywood, but professionally they were unfulfilling years. Following standard procedure, MGM’s casting department ordered him to do a screen test, but, preposterously, they asked him to read for the straight role of an English vicar in Robert Z. Leonard’s 1940 version of Pride and Prejudice. Silvers’s Brooklyn locutions rendered the scene unintentionally funny—“My dear Dame Elizabeth, your modesty does you no dis-soy-vice”—and he believed that the test, which he later pulled strings to have destroyed, derailed his early film career. “It was the damnedest thing,” says the clarinetist Artie Shaw, who was a Hollywood friend of Silvers’s and actually saw the screen test. “It was funny, but [directors] didn’t think it was funny; they thought, This guy can’t act. They didn’t know he was a funny man. He wore glasses, so they just thought, Treat him as a serious prime minister or something.”

Silvers couldn’t get a part in the movies, but, well compensated by MGM and expert at schmoozing, he kept busy entertaining at Hollywood parties and being every big star’s favorite goofball buddy. “He was hilarious in a living room—much funnier than he was doing dialogue in a movie or TV,” says Jo-Carroll Dennison, Silvers’s first wife, who had been signed to a Twentieth Century Fox contract after she won the 1942 Miss America pageant. “Phil was friends with all the groups—the Sinatra group, the Gene Kelly group, the Groucho group,” Dennison says. “Groucho and George Bums, their group I didn’t like—their humor was cruel. But the Gene Kelly group was unique, in that people dropped by every Saturday night. You never knew who you were gonna see: Judy Garland, Noel Coward, Paul Robeson, Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, Saul Chaplin. They liked to play volleyball in the backyard, and they danced and did charades. Bing Crosby’s group was more staid—songwriters like Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen, and comedy writers. And Sinatra was much the same thing: comedy writers, songwriters.”

Silvers, a wanna-be musician who tootled on a clarinet for fun, collected songwriters as friends. He’d been close to Saul Chaplin and Sammy Cahn since they’d all worked summers together in the Catskills in the early 1930s, and reveled in knowing the likes of Jerome Kern, Jule Styne, Johnny Mercer, Burke, and Van Heusen. It was an idle comment at the home of Burke, the lyricist of “Misty,” that led to Silvers’s sole songwriting credit. When Silvers described Burke’s wife as “Bessie with the laughing face,” Van Heusen, Burke’s frequent writing partner, commented, “Good title for a song.” Burke replied, “It’s my day off—you two guys do it,” leaving Silvers to do the job with Van Heusen. A few days later, at Sinatra’s daughter Nancy’s birthday party, Silvers presented the finished song with “Nancy” substituted for “Bessie.” Sinatra liked the song so much he made it part of his concert repertoire, and the rest is big-room history.

Encouraged by his friends, Silvers was soon doing his antic living-room shtick in nightclubs such as Ciro’s and Charlie Foy’s Supper Club, first solo, and then, when Rags Ragland rolled into town to do character parts in the movies, as half of a duo. But even as he became the consummate insiders’ star, a chic namedrop even for the studio heads—Mayer asked him to perform at a company function, Paramount’s Buddy DeSylva told Silvers he was his favorite comedian, and Columbia’s Harry Cohn tapped Silvers to help him coordinate his studio’s segment of a wartime show for servicemen—none of the big bosses had any real use for him in pictures. Darryl Zanuck, of Twentieth Century Fox, was the most obliging, signing up Silvers after his MGM contract expired and keeping him at the studio for nine years. But in movie after movie, from Footlight Serenade to My Gal Sal to Coney Island, Silvers kept playing the same role, the affable best pal of the male lead and brother-confessor confidant of the female lead—a stock character he called Blinky. “I’d follow John Payne or Victor Mature around, and I had the same opening line in every picture,” he remembered in 1981. “Somewhere in the middle of the first act, I’d come running in and say, ‘I’ve got the stuff in the car!’ To this day, I don’t know what the stuff in the car was.” A sympathetic Gene Kelly cast Silvers in two of his better musicals, Cover Girl and Summer Stock, but still in undeniably Blinkyish roles.

Silvers played Blinky in real life, too. When Judy Garland had the hots for Artie Shaw, it was Silvers to whom she mooned about her unrequited love for the clarinetist, and it was to Silvers that Shaw frequently left the job of cleaning up the messes he made with his womanizing. Shaw, who rivaled Orson Welles as the cocksman supreme of the 1940s, was unofficially engaged to Betty Grable when, in 1940, he eloped with Lana Turner to Las Vegas—Silvers had only just introduced them on the set of MGM’s Two Girls on Broadway, where Turner was wearing a dress Shaw remembers as “so tight you could see every pore in her body.” After the elopement, it fell to Silvers to dry the tears of both Grable and Garland. “He told Betty about me marrying Lana. She hadn’t heard about it,” Shaw says. “And she said, ‘It must have come on him suddenly.’ Come on him— Betty was not the smartest girl in the world. Yeah, Phil was always around, just the kind of capon part he played in the movies. It’s as if he were ball-less.”

Even Dennison, to whom Silvers was married for five years, says her initial attraction to him was that “he wasn’t on the make. He was just fun to be with, made me laugh, and didn’t try to get me into bed.” For all of his assignations with strippers in burlesque, Silvers wasn’t confident about his looks and relied on his sense of humor to charm women, which made him an ideal platonic date—Audrey Hepburn regularly sought him out as her escort for premieres—if not an ideal husband. Dennison says their marriage unraveled because, as kindly and funny as he was, Silvers was clueless about romance and the day-to-day responsibilities of being in a relationship. They married in a civil ceremony on a Friday, “and I had gotten all these nice black nightgowns and negligees with fur, and mules—the whole thing—for my big wedding night, which I expected to be very romantic. And, instead, it was Friday, so Phil expected that we would go to the American Legion fights. And I hated the fights. Danny Kaye happened by to give us a wedding present, and I was in tears, and Danny said, ‘What’s happening?’ ‘Well, he wants to go to the fights, and it’s my wedding night.’ He was outraged: ‘u can’t do that, Phil!’ And Phil, in all innocence—clearly just totally bewildered by this whole thing—said, ‘But it’s Friday night! I always go to the fights on Friday night!’ That sums up our relationship, I think, better than anything else.”

It didn’t help that, just a few days after their wedding, Silvers accepted Frank Sinatra’s request to join him on a U.S.O. tour of Europe, leaving Dennison behind for several weeks. Nor did it help that Silvers was hooked on playing the ponies and shooting craps in Vegas, and was developing a rep as one of Hollywood’s A-list compulsive gamblers. His loving Jewish mother saved him by sending out his drab, responsible older brother, Harry, to manage his money and keep an eye on him—“Harry the Nudnik, we called him,” says Shaw—but Silvers was constantly fretting about cash flow and his debts to bookies. “Everybody knew Phil gambled—it was his reputation,” says Buttons. “Just like we all knew about Walter Matthau gambling. I mean, these guys would bet you on whether it’s gonna rain tomorrow, or which way the wind was blowing, or how many people are gonna walk through the front door of a restaurant. It was all-consuming, almost like a disease.

Silvers always did his best work in New York, and twice during his Hollywood years Broadway afforded him a chance to build upon what he’d accomplished in burlesque and Yokel Boy. In 1947, Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne put together a stage musical, called High Button Shoes, that was based on a nostalgic novel by Stephen Longstreet about his upbringing in New Jersey during the Taft years. As had happened with Yokel Boy, the writers reconceived the show when Silvers got involved, building it up around a previously minor character named Harrison Floy—“a flamboyant scamp with great dreams, a Bilko in spats,” as Silvers described him. George Abbott, the leading stage director of the period, came aboard as the director and script doctor, and Jerome Robbins as the choreographer. But despite the show’s promising pedigree, it, like Yokel Boy, struggled in outof-town tryouts, and Silvers once again took it upon himself to ad-lib the show into hitdom, drawing upon old bits he’d done in burlesque. High Button Shoes ran for 727 performances in New York.

Top Banana, Silvers’s triumphant moment onstage, came four years later. Hy Kraft, a writer acquaintance of Silvers’s, had come up with the idea of doing a musical about a comedian; it was called Jest for Laughs, and Johnny Mercer had agreed to write the songs. Silvers found Kraft’s material to be as corny as his working title and suggested that he and Kraft come up with a new angle. At the time, Milton Berle was enjoying his first flush of success as Mr. Television. Silvers thought it would be funny to parody his old friend and do a show about a tightly wound former burlesque comic (renamed Jerry Biffle to avoid libel suits) who had now become a huge, difficult television star. Rose Marie, the female lead in the show, remembers its conception’s being every bit as seat-of-the-pants as Silvers’s previous Broadway adventures. “Phil called and said, ‘I want you to do this show with me,”’ she says. “I said, ‘Well, send me a script.’ It wasn’t even a show—it was 12 pages! I said, ‘Where the hell’s the show?’ And he said, ‘Well, we’ll do it as we do it.’”

"Most burlesque people had no self-respect or respect for each other. But Phil was different,"says Sherry Britton.

Unlike Yokel Boy and High Button Shoes, though, which received emergency infusions of burlesquerie, Top Banana was, from almost the get-go, a willful evocation of Gaiety-style hysteria, with some early television satire thrown in. (Though “first banana” was the proper term for a leading comic in burlesque, Mercer thought “top banana” had a better ring to it.) “Phil called every burlesque comic in the world to be in it, which was unbelievable,” says Rose Marie. He enlisted his former mentor, Herbie Faye, as well as Faye’s brother Joey and Jack Albertson, a confrere from his early days with the Minskys (who later resurfaced in Chico and the Man). Walter Dare Wahl, an aged comedian and former wrestling champion who’d done a great bit decades earlier in vaudeville in which his limbs became hopelessly entangled with his partner’s, was exhumed from obscurity to play Jerry Biffle’s masseur, just so he and Silvers could revive the bit.

The only sticky business was how to break the news of the show to Berle. Silvers had a date to play golf with him, and, in the course of the game, Berle asked about the new musical he’d heard about. Silvers, with a degree of hesitancy, explained that it was “about a guy who’s been ‘on’ all his life. His only goal is the laugh.... Everything to him is a comedy bit. If he has a girl, it’s the girl bit— He never listens to anyone’s conversation— he’s just thinking of what he’ll say next. The poor guy never had a chance to develop in any other areas.” Berle, after a pause, replied, all smiles, “I’ll be a sonovabitch—I know guys just like that!”

Top Banana, whose book and songs were developed on the fly during rehearsals, proved to be one of the most explosively funny and well-reviewed musicals ever to play on Broadway. For Mel Brooks, who was a young writer at Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows at the time, seeing the musical was a defining experience. “What can I tell you? He had more pep and energy than I’ve ever seen in a leading comic,” Brooks says. “He got in the middle of the two guys doing an old-fashioned stuck-together—hands, arms—and he was literally hysterical. I can’t even describe it. Top Banana taught me a lot about how to write a Broadway show to get really big laughs. When I was writing The Producers, I said, ‘I’ve gotta bring that back to the theater.’ It was a mandate to me.”

"Off-camera, he'd sit by himself and just be musing. It seemed like he wanted to be friendly, but it wasn’t in his nature."

Playing for a little under a year on Broadway and a further two years on national tour, Top Banana looked to be a career high-water mark for Silvers. Yet he wasn’t particularly content. He was frustrated by Hollywood’s misuse of him, his gambling still bedeviled him, he was often stricken with pre-show hot sweats and anxiety attacks he called “the whammies,” and he was not helped by psychotherapy— though his newfound interest in the writings of Sigmund Freud and Baruch Spinoza did produce a fortuitous moment onstage. During one performance of Top Banana, he accidentally addressed a young male cast member as “Honey”; catching himself, he explained that he’d made a Freudian slip, then launched into a protracted, extemporaneous monologue about a famous debate between Freud and Spinoza, who in reality had lived two centuries apart. After an awesome, prolix display of psychological gobbledygook that had everyone onstage getting nervous—“It went on a good five minutes,” Rose Marie says—Silvers wound up his ad-lib by announcing that Freud finally convinced Spinoza of his argument, and fed his bewildered castmate the prompt “You know how?” The young man obligingly asked, “How?” “He hit him!” Silvers replied. “It got the biggest scream you’ve ever heard,” says Rose Marie. The FreudSpinoza bit was permanently written into the show.

When Top Banana finally ended its run, Silvers bided his time in another Blinky part, in the half-cocked Doris Day movie Lucky Me. The same year, 1954, he agreed to be an M.C. at the annual White House Correspondents Dinner, which turned out to be the more auspicious engagement—he knocked ’em dead, convulsing Eisenhower and catching the attention of another audience member, Hubbell Robinson Jr., the head of programming at CBS. A few days later, Robinson called Silvers to propose that he develop a new half-hour sitcom with the writer Nat Hiken.

It was a shrewd pairing—Hiken, if quieter and more intellectual than Silvers, had the same shtetl blood coursing through his veins (though he had grown up in Milwaukee rather than Brooklyn) and, like Silvers, felt insufficiently respected in middle age. Hiken had labored for years as the great unsung comedy writer of the broadcast industry, working first for the radio comedian Fred Allen and then, in the early 50s, for Martha Raye’s variety program on NBC. Though his fellow writers recognized him as a borderline genius, Hiken was frustrated by the lack of credit accorded him, particularly by Allen, who was notorious for claiming he wrote all his own material. Hiken was an amateur pilot, and one of his running jokes was that he once had to make an emergency landing on a remote Indian reservation near the Grand Canyon, where the chief asked him what he did for a living. When he told the chief that he wrote for The Fred Allen Show, he claims, the chief laughed dismissively and replied, through a translator, “Everyone know Fred Allen write his own material!”

The very first concept that Hiken came up with was to make Silvers a sergeant in a U.S. Army camp, an idea Silvers initially dismissed as too “Abbott and Costello ... dumb drills, guys bumping into each other and their pants falling down.” But Silvers soon came around to the idea, recognizing the chance to continue the Punko Parks-Harrison Floy-Jerry Biffle line of connivers. He’d once again have a chance to incorporate all his old burlesque tricks, but, this time, within a framework of intricate, twisty plots, Hiken’s forte. Hiken, for his part, wisely recognized that Silvers, no matter what the role, always essentially played Phil Silvers. Though the show was more tightly plotted and adlib-averse than anything Silvers had done before, Hiken made a point of drawing upon Silvers’s own quirks and foibles, in particular his gambling habit, to shape Ernie Bilko.

The program’s original title, in fact, was You’ll Never Get Rich, and in one of the best episodes of the first season, “The Twitch,” Hiken was particularly to the point. The premise was that Colonel Hall had become disgusted with the epidemic gambling and poker playing in Bilko’s platoon, and was bringing in a clean-cut captain to put the fellas right. (Clean-cut captains on Bilko are like the young ensigns in red tunics on Star Trek—you know from the beginning of the episode that they’re doomed.) The captain’s plan was to culturally educate the boys by having his proper wife (played by Charlotte Rae) deliver a lecture on Beethoven. Bilko knew he had to get his men to attend the lecture, but didn’t know how to swing it—until he noticed that the captain’s wife had a nervous tic, a habit of periodically tugging at her girdle. Soon enough, he’d organized a betting pool, first at Fort Baxter, then extending to army bases across the country, on how many times the woman would twitch during her lecture. The climactic scene is sublimely funny, with the woman delightedly addressing a packed hall but puzzling over the men’s periodic unison pronouncements of “One ... Two ... Three ... Four ...” Bilko’s shenanigans are ultimately foiled, as all Bilko shenanigans must be, when Colonel Hall walks in on some soldiers who are illicitly broadcasting the twitch count on the radio, ball-game-style, to the other army bases.

Terrific as Hiken was at plotting, he was equally good at casting—like The Sopranos David Chase, he loved un-Hollywood faces and was adept at getting the most out of both seasoned character actors and nonperformers who just looked right. When he was working on Martha Raye’s show, he’d successfully made use of the comic-sketch ability of the boxer Rocky Graziano. For The Phil Silvers Show, Graziano acted as a de facto casting assistant, bringing aboard the gnarled but handsome middleweight Walter Cartier to play one private, Dillingham, and enlisting his own former manager, a slab-featured pug-mug named Jack Healy, to play Private Mullen. “Mullen, he was a wiseguy,” says Mickey Freeman, the pip-squeak stand-up comic who played the banty private Fielding Zimmerman. “He brought Rocky Graziano to the Mob and they gave him points. But he was a very nice man.” When Harry Clark, the gruff, burly actor who played the company cook, died midway through the first season, the show’s producers asked Freeman to help track down a fellow stand-up comic, an obscure, low-rent gagman named Joe E. Ross—“which was like Noel Coward saying, ‘Can I get Sadie Banks?,’ who was a burlesque girl,” Freeman says. “Joe E. was not a great comic. But he had a quality—rough.” Ross was duly located in Hawaii, where he was working in a strip club. After he arrived in New York to take the part of company cook Sergeant Rupert Ritzik, he confided to Freeman that he’d been mid-coitus with a lady acrobat when the casting agent called, and wasn’t sure if he should have accepted CBS’s offer. “He said, ‘What am I doing?,”’ Freeman says. “T’ve got the sun, I’ve got the ocean, and I’ve got the acrobat—what else do I need?”’ Ross ended up staying for Bilko’s entire run and co-starring with Fred Gwynne in Hiken’s next series, Car 54, Where Are You?

Even the professionals in the Phil Silvers Show cast were humorously misshapen—the broken-nosed comic Billy Sands, who played Private Paparelli; the pudgy, bug-eyed character actor Maurice Brenner, who played Private Fleischman; and good old Herbie Faye, brought in by the ever loyal Silvers to play Corporal Fender. Hiken also recruited a few actors who’d done service in other militarythemed shows. Paul Ford had already played his share of addled officers before becoming Colonel Hall, and was appearing as another colonel on Broadway in The Teahouse of the August Moon. Allan Melvin and Harvey Lembeck, the beanpole-fireplug combo who played Bilko’s two henchmen, Corporals Henshaw and Barbella, were both plucked from the Broadway play Stalag 17, where they were also playing soldiers. (And lest you think of John Frankenheimer’s 1962 film The Manchurian Candidate as an unremittingly sober Cold War exercise, note that two of the brainwashed soldiers in that movie are named ... Melvin and Lembeck.) Audaciously for the time, Hiken, who wanted the platoon to look like a real army platoon, cast a couple of black actors, P. Jay Sidney and Terry Carter, as Privates Palmer and Sugarman, even though this discomfited some advertisers in the South.

The final assemblage of talent simultaneously impressed for being so compellingly street-real and begged some serious suspension of disbelief—particularly the idea of the weedy, 5 6-year-old Faye passing for an enlisted man. But the whole thing worked in a glorious, deze-and-doze, Runyonesque sort of way. “Nat Hiken had a genius for putting together a group of people who were perfect in what they did. All of us were absolutely right for what we were doing, if not for anything else,” says Brenner, who, along with Freeman and Melvin, survives as a keeper of the Bilko flame. The eldest of Silvers’s five daughters, Tracey, was born during the show’s run—he had married his second wife, a Revlon model named Evelyn Patrick, in 1956—and she remembers referring to her father’s program as “Daddy and the Dirty Men.”

T he Phil Silvers Show faced one major crisis on the way to its premiere on September 20, 1955: CBS scheduled it for Tuesday night at 8:30—opposite Berle’s blockbuster variety series on NBC, which was a television fixture, having been on the air for six years. Even Berle felt sorry for Silvers when he heard the news. “I’ll kill you,” he said, more out of concern than competition. “For your sake, move the night!” Indeed, the Berle show walloped the Silvers show the first few weeks, winning in the ratings by an almost two-to-one ratio. But after a few weeks, as word of mouth spread, and after Silvers made a guest appearance with the Fort Baxter platoon on The Ed Sullivan Show, the numbers started to shift, and soon Berle was the one getting trounced. It turned out to be the death knell for Berle’s run as King of Tuesday Night, a circumstance he handled with remarkable magnanimity, particularly given that Silvers had zinged him before with Top Banana. “Milton sent a telegram: I TOLD YOU TO MOVE TO ANOTHER NIGHT!” says Tracey Silvers. “It was bizarre, because you think they would have fallen out. But Milton and my dad were around each other when they were children—they had a whole life history together. The great thing about them was, at the Hillcrest Country Club [just south of Beverly Hills], which everyone belonged to at the time, there would be this table of Phil Silvers, Jack Benny, and Milton Berle, and they would sit around and help each other with their acts: this brotherhood of comedians. Try to imagine, you know, Jim Carrey and Steve Martin sitting around, helping each other. It’s almost incomprehensible.”

Life on the set of The Phil Silvers Show, which was rehearsed above Lindy’s restaurant on West 52nd Street and filmed at the old DuMont television studio on East 67th, was exactly what you’d have expected of a mostly stag show set on an army base. “The minute we were through with a scene, we all raced to a table to play poker,” says Brenner. “The game went on for years, nickel and dime,” says Freeman. “We played that stake just so it would not become too involved. And Phil used to come out and say, ‘Can I play here?’ We said, ‘Yeah. But inside, you’re a star—out here, you’re unemployed.’ So he used to sit and play with us, nickel and dime. However, he’d say to me, ‘I’ll give you half the nickel on hearts, half the nickel on spades.’ He had the whole board covered with different bets.”

The boys were all suitably awed by Silvers’s talent; if you watch some episodes closely, you can see G.I.’s laboring mightily in the background to stifle laughs as they watch him perform. Melvin found Silvers’s scenes with Colonel Hall especially priceless, particularly the running gag in which Bilko sought to win the colonel’s favor by showering his easily flattered wife (Hope Sansberry) with over-the-top compliments. “Phil’s association with the colonel I found so amusing—that he would do these little dodges of his,” Melvin says. “But he was always so aware that the colonel was going to get hip to it. And then the bit with the wife. [Perfect Bilko impression.] ‘Colonel, you didn’t tell me there was a movie star on the post—heavens, it’s Mrs. Hall!’ ‘Colonel, you didn’t tell me your daughter was visiting for the weekend—why, bless my soul, it’s Mrs. Hall!”’ (At times, Bilko’s flattery of Mrs. Hall verges on gay camp. In “The Twitch,” he gushes madly, “You make a sofa a throne! When are you going to get one of those Italian boy cuts and drive the post out of its mind?”)

Even in these fun times, though, the cast members noticed, as Rose Marie had backstage at Top Banana, that Silvers was occasionally gripped by a palpable melancholia. “It was strange with Phil,” says Melvin, a TV lifer who went on to play Sam the Butcher on The Brady Bunch, and Archie Bunker’s friend Barney on All in the Family. “You know how sort of bombastic and open and wild he was on-camera. When he was off-camera, he’d sort of sit by himself and he’d just be ... musing. I used to go and sit and chat with him. And it seemed like he wanted to be friendly and open, but it just wasn’t in his nature.”

But Silvers did join the guys in their amusement over Maurice Gosfield, otherwise known as Private Duane Doberman, who had a name fit for a symphony conductor but the face of a dyspeptic, overfed marmoset. The show’s other Maurice, Brenner, had already been cast to play the part of Doberman, but as soon as Gosfield walked into an open casting call—a short, plump, appallingly hideous man with a high, raspy voice and a perpetual grimace—Hiken knew he had the right man for the job. Many of the best Bilko episodes are constructed around Gosfield, an actor of extremely limited range whom Hiken deployed deftly as both a sight gag (Doberman is mistakenly chosen to be the face of the U.S. Army on a recruiting poster) and a teddy-bear object of sympathy (Doberman hangs his head balefully when no one wants to date his sister). “Doberman used to destroy Phil,” says Melvin. “Phil looked at Doberman as a kind of ... he didn’t know what he was, or how he functioned. He always had the head cocked to his side, and he’d sort of crab over—there were never any definite steps or anything. His movements, and his whole persona, were sort of baffling.” And Gosfield was every bit as slovenly in real life as his forlorn character was—“notorious for breaking wind,” says Brenner. “The smell would spread, and it was so bad, Nat would take one whiff and say, ‘All right, let’s take 10 minutes.’ Just to let the room clear.”

As soon as The Phil Silvers Show became a hit, Doberman became the most popular character on the show. Gosfield received more fan mail than even Silvers, and was in high demand in society circles as a sort of found-object source of amusement. “The Beautiful People of New York invited him to their cocktail parties; he was the rage of the playboys on Fire Island,” wrote Silvers in his memoir. Silvers took this circumstance in stride in public; in the pre-show warm-ups before the live audience, he’d bring Gosfield out and introduce him as “the real star of our show.” But privately he was a little miffed that all this attention was being lavished on a man who was essentially a nonperformer (Gosfield, though he could barely blurt out his lines, was even nominated for an Emmy one year), and in his memoir Silvers noted with irritation that Gosfield came to believe he was actually a great actor, and started to carry himself with hauteur: “Off camera, Dobie thought of himself as Cary Grant playing a short, plump man.” After The Phil Silvers Show, the only serious employment Gosfield found was as the voice of Benny the Ball in the HannaBarbera cartoon Top Cat— essentially Bilko transposed to a feline realm—and he was the first of the series regulars to die, in 1964.

The Phil Silvers Show whizzed by quickly, both in terms of its breakneck pace—most of the half-hour episodes were shot live, in sequence, in long takes, in less than an hour—and in its time on the air as an original series. By 1959, just four years after it had started filming, Silvers and the boys were done. CBS pulled the show for financial reasons. Though it was getting better Nielsen ratings than ever— even as its quality had slipped a bit, owing to Hiken’s burnout-induced departure halfway through its run—it was expensive to produce owing to its large cast, and CBS’s executives thought they could score a more lucrative syndication deal for the show while it was still hot. (This was before networks realized that a series could run in daily syndication even as it continued to film new episodes for nighttime viewing.) The platoon dispersed, and Silvers went back to Broadway, starring in Do Re Mi, a minor musical hit with songs by Jule Styne, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green.

In his post-Bilko years, Silvers became, and remained until his death, a Californian—a move that enabled him to while away the hours at the Hillcrest Country Club and the Nate ’n A1 delicatessen with his comedian friends, most of whom had also relocated to palmy Beverly Hills; Berle lived two houses down from him on Alpine Drive. But karmically, L.A. was unfavorable to Silvers, who had a history of flourishing in New York and struggling in Hollywood. His California years were not without their moments—he was one of the few comics who were actually funny in It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Stanley Kramer’s all-star UltraPanavision bloatathon, and he had a charming reunion with Buddy Ebsen when he took a recurring role as a con man on The Beverly Hillbillies—but he failed in his 1963 attempt at another TV series, The New Phil Silvers Show, which had him playing a foreman in a factory, and his personal life got messier as the 60s went on. He developed glaucoma in both eyes, which adversely affected his balance and agility as a performer, and he plunged into a deep depression from which he never completely recovered. He also continued to gamble incessantly. The Silvers family never wanted for anything materially; between good management and Silvers’s 50 percent ownership of Gilligan’s Island, which he co-produced with Sherwood Schwartz, solvency was not a problem. But Silvers’s thrall to his addiction, compounded by his depression, made him unpleasant company sometimes. Frank Capitelli, the longtime maitre d’ of the New rk branch of the Friars Club, remembers Silvers as “not my cup of tea, not a happy man. When you gamble, you are not a happy person.”

"He became the kind of angry that a lot of comics become," recalls Freddie Fields. "He'd get unreal."

Evidently, it all got to be too much for Silvers’s wife, Evelyn, who literally set his packed belongings out on the front lawn one day in 1966. He came home from the Hillcrest club and was totally blindsided, just as he’d been in the late 40s when Dennison asked him for a divorce. “He was stunned, and I think it was just something he never got over,” says his daughter Tracey. “My dad would have stayed with my mom. And he would have stayed with Jo-Carroll.” After a lifetime of living in hotels, working nights, and playing cards till sunrise with the guys in the orchestra pit, Silvers never quite adapted to being husband material. (Evelyn Silvers, who still lives in Beverly Hills, declined to be interviewed for this article.)

This, however, did not preclude his being a good parent to his five daughters. Silvers always had a natural rapport with children. “When I was a little boy, I used to see him all the time at my parents’ house in Palm Springs,” says Frank Sinatra Jr. “And I loved seeing him. He’d go ‘Woof, woof’ at me, and I used to go ‘Scram, doggy!’ and giggle.” Judy Garland, witnessing Silvers’s ease with kids, chose him to be Liza Minnelli’s godfather. His own children, too, considered him the ideal playful, doting grown-up. “He would have been a content bachelor, but having children was a great thing for him,” says Tracey Silvers. “Because he liked children—he didn’t feel uncomfortable around them. He would play these little-kid tricks on us all the time. My sister worked at a movie theater once, selling tickets in the little booth out front, and he’d come with his clarinet and stand under the marquee, serenading her while she sold tickets. And though he was gone a lot, when he was there, he was very there. When I was up sick in the middle of the night, it was my dad with me, not my mom. And if you wanted to discuss a problem with him, he would sit down and really discuss it with you—he would have a serious, deep conversation and try to help you.”

In 1972, Silvers enjoyed one last, brief career upswing—in New York, naturally. He returned to Broadway as the lead in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (a role that he’d passed on a decade earlier, opening the door for Zero Mostel) and became the first-ever performer to win the best-actor Tony in a revival. At the awards ceremony, Silvers, perhaps recognizing that this might be his big valedictory moment, delivered a rambling, emotional acceptance speech. A few days later, he suffered a debilitating stroke that paralyzed his entire left side and closed down the show. Though he regained his ability to move and speak through intensive therapy, “it was the beginning of the end for him,” says Freddie Fields, who’d been Silvers’s agent and close friend since the Bilko years. “He became the kind of angry that a lot of comics become. He would lash out: ‘Why couldn’t I do that?’ ‘Why didn’t I get a chance at that?’ ‘Why is Paul Newman playing Butch Cassidy?’ He’d get unreal. And it was a pressure on me, because I didn’t have a relationship with him where I could go out and say, ‘Hey, listen, asshole, go fuck yourself.’ The truth is not in an agent’s vocabulary at that time.” When Kenneth Tynan, unaware of the stroke, saw Silvers in a touring production of A Funny Thing in England two years later, he initially suspected Silvers of being hung over, which he found odd, knowing that the comic hardly ever drank. He was saddened to see the old-timer struggling, and, after a post-show supper with Silvers during which the two former phenoms reminisced about days gone by (“Like many of these Jewish non-drinkers, he has total recall,” Tynan wrote), the critic confided to his diary, “I have the bleak and comfortless premonition that he may not have long to live.” (In fact, Silvers outlived Tynan by five years.)

Tracey Silvers says her father was “very happy and very sad” at the end of his life. It got him down that he was wifeless and not working, but, unlike many faded midcentury stars, he did not regard the 60s, 70s, and 80s as a blaring, incomprehensible sensory assault on everything he held dear. He enjoyed the music of the Beatles, she says, admired Michael J. Fox’s work on Family Ties, and “thought Airplane! was hysterical.” His acting career ended on a poignant note, with a guest spot on ABC’s Happy Days late in that show’s run. His daughter Cathy had a recurring role as Joanie Cunningham’s best friend, Jenny Piccalo, and Silvers appeared as Mr. Piccalo, her dad.

Thereafter, Silvers, who looked much older than his 70-odd years, lived the retiree’s life in his apartment in the Century Towers, an enormous condominium complex built on what was once the Twentieth Century Fox back lot. There, upon the very same acreage where he’d served time as Blinky, Silvers, usually in the company of his daughter Tracey and her husband, an independent filmmaker named Iren Koster, spent his final days watching movies and eating copious quantities of Mallomars, his favorite snack. It was Koster who found Silvers the afternoon he died. He’d been napping, and he lay in bed, his arms neatly folded on his chest, his bald head covered by the wool knit cap he wore to keep warm, his face caught in a beatific smile—as if he’d been dreaming of a perfect ad-lib at the Gaiety, or of hitting a four-horse parlay at Belmont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now