Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

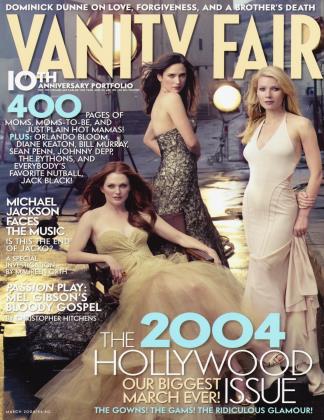

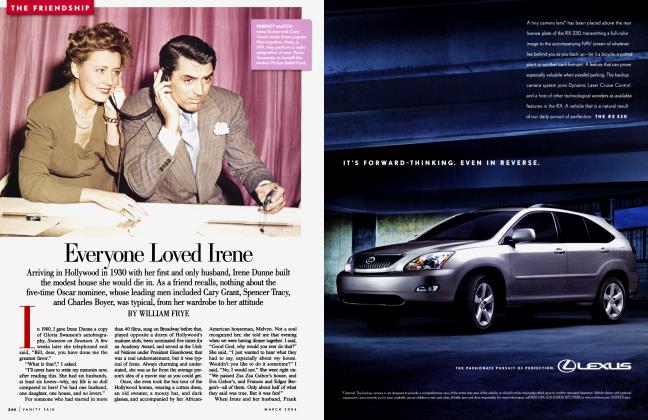

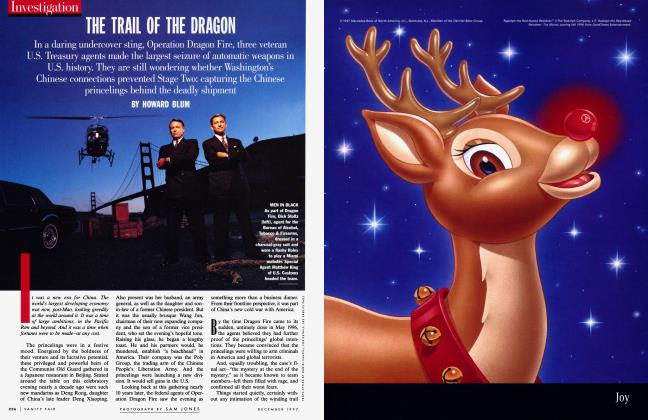

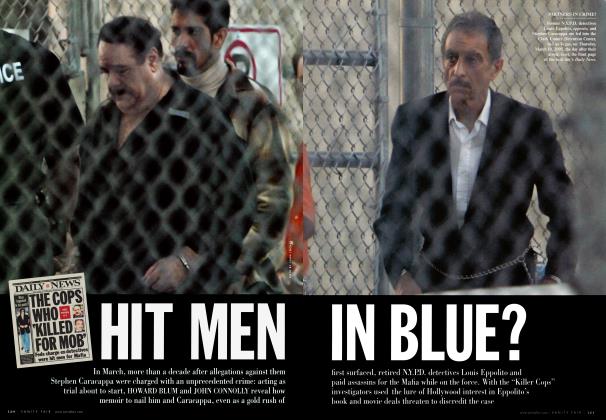

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAnthony Pellicano was the go-to guy for everyone from Michael Jackson to Don Simpson. Now, jailed for possession of explosives, the notorious private investigator has become the problem, as a grand jury probes what A-list lawyers and their famous clients knew about Pellicano's secret wiretapping operation

March 2004 Howard Blum, John ConnollyAnthony Pellicano was the go-to guy for everyone from Michael Jackson to Don Simpson. Now, jailed for possession of explosives, the notorious private investigator has become the problem, as a grand jury probes what A-list lawyers and their famous clients knew about Pellicano's secret wiretapping operation

March 2004 Howard Blum, John ConnollyThe man got right to it: the original plan had been to blow up Busch's car. Shaking with fear, she put down the phone.Within 24 tense hours, Anita Busch received two warnings. And each in its own chilling way had unforeseen and increasingly momentous consequences.

The first came early on a bright, lush California morning near the end of June 2002. It was not much past eight, yet Busch, 42, was already out the door, eager to get to her desk at the Los Angeles Times; it was always like this when she was chasing a story. Tall, blonde, a whirl of long-legged, no-nonsense strides, she hurried across the narrow residential West Side street toward the spot where she had parked her silver Audi convertible the night before. Halfway there, she stopped: the windshield had been smashed into a spiderweb of glassy veins.

At first she was simply annoyed, shaking her head and silently cursing the neighborhood kids who undoubtedly were responsible. Now she’d need to spend the morning getting the windshield replaced instead of working the phone.

For three busy weeks she had been digging almost nonstop into the venomous charges and countercharges flying back and forth between Hollywood tough guy Steven Seagal, the actor, and his onetime producing partner Jules Nasso, who, federal authorities alleged, was a Staten Island tough guy—an associate of the Gambino crime family. Only, this morning, rather than following the provocative lead she was growing convinced contained a nugget of headline-making truth, she’d need to put the story aside.

Then she got closer to the Audi. A tinfoil baking tray was balanced on the windshield. Next to what looked like a bullet hole. And a note was taped just above. Its message, in red block letters, was one word: STOP.

In that instant, she understood: This was about her story. (Vanity Fair contributing editor Ned Zeman, in preparing his own story on Seagal and Nasso, was also threatened.)

Later that morning, police detectives and F.B.I. agents gathered in Busch’s small living room and peppered her with questions about her story that, for fear of revealing her sources, she defiantly refused to answer. At the same time the bomb squad dealt with the tin tray on the windshield. Cautiously, the experts turned it over. Inside was a dead fish and a red rose.

The car was now evidence in a criminal investigation, and a flatbed truck arrived to carry it away. Except that the bomb squad had left, and none of the remaining cops was willing to drive it onto the truck. What if the Audi’s ignition was wired to a bomb? So while the authorities shrugged their shoulders in confusion, one of Busch’s reporter friends, Dave Robb, took the keys from her and coolly drove the car without incident up onto the truck. That helped ease some of her fears.

But the next day, June 21, the calls started. By 11 A.M. six messages had been left on her office voice mail. They were all from the same man. All, he said in a deep rumble, prompted by the incident with her car. And all, he promised, “urgent.”

When she finally called back, the man got right to it: the original plan had been to blow up her car. Shaking with fear, she put down the phone. A moment later, Busch called the F.B.I.

It was this brief, anxious conversation with F.B.I. agent Stan Ornellas that set in motion over the next 19 months an escalating succession of dramatic events. It led to the imprisonment of Anthony Pellicano, a celebrated gumshoe to the stars. To the discovery of wiretaps and provocative rumors about them. And to the convening of a Los Angeles federal grand jury that is still hearing testimony involving an A-list cast of Hollywood stars, managers, producers, and lawyers.

Boldfaced names such as Warren Beatty, Sylvester Stallone, Garry Shandling, and manager-producer Brad Grey have all been questioned by the F.B.I. Additional scrutiny has been focused on a prestigious circle of Los Angeles lawyers, including Bert Fields, whose clients over the years have included Tom Cruise, Michael Jackson, and DreamWorks executive Jeffrey Katzenberg; Edward Masry, the litigator whose legal crusade alongside Erin Brockovich inspired the movie that bore her name; Martin Singer, who has represented Steven Seagal, Mike Myers, and Arnold Schwarzenegger; as well as divorce attorney Dennis M. Wasser, whose firm routinely deals with irreconcilable differences between the very rich and very famous.

None of the celebrities or lawyers has been charged with any wrongdoing. Nevertheless, in its meandering way, what started as a small scene out of a B movie has evolved into an ongoing HighConcept mystery that offers the tantalizing promise of revealing how the industry’s high-stakes business is routinely conducted and also some of its best-kept dirty little secrets.

But on that uncommonly warm afternoon in June 2002, Agent Ornellas had no intimation of the star-studded trail that lay ahead. He simply asked Busch if the caller had left his name.

And when she shared it, he never let on that he already knew the man. Or that the man was already working with the F.B.I.

The man got right to it: the original plan had been to blow up Busch's car. Shaking with fear, she put down the phone.

The F.B.I.’s C.E.-4 squad works out of a grim, gray federal-building tower on Wilshire Boulevard, just a short ride in one of the bureau’s Ford Tauruses from the gaudy heartland of the entertainment industry. But showbiz is not their beat. “C.E.” stands for “criminal enterprise,” bureau-speak straight from the Hoover Building in Washington for what used to be called “organized crime.”

So when Ornellas, 54, heard that one of his Confidential Informants, a middle-aged former engineer who was knee-deep in the business of manufacturing and distributing Ecstasy and who was already under indictment for a laundry list of federal charges, was making phone calls to the reporter, his instinct was that it wouldn’t take much to wrap the whole sordid thing up. Or at least that was what he confided to some of his colleagues before he and his 44-year-old partner, Tom Ballard, went to pay a call on the onetime engineer.

Like most teams, Ornellas and Ballard have a well-practiced rhythm to their interviews. Ballard, the younger, hipper of the pair, always affable and breezy, is the good cop. While Ornellas, an imposing bear of a man, a 26-year F.B.I. veteran, is the even better cop. Rigidly formal in his demeanor, Ornellas has a gift not only for listening but also for seeming to care.

Without much prodding The Engineer shared his story:

About four or five days before, Alex, a small-time drug runner who was always trying to wheedle a load of Ecstasy out of him, got to talking about his latest gig. “Some people back East,” the F.B.I. later quoted Alex in an affidavit, wanted to stop a female reporter from writing about Steven Seagal, and Alex had been hired by a detective agency to bum her car as a warning. Thing was, he complained, it was shaping up to be a “tough job.” He had scoped it out, and in the apartment right above where the reporter parked her car each night there was someone who never seemed to turn out the lights and go to bed. Alex’s instinct was to take a pass, but he knew the people back East were “ruthless” and would “get somebody to do it.”

In one of Bert Fields's novels a detective cuts a lawyer off. "Don't ask me how I know. You don't wanna know."

Even as they listened to this story, the F.B.I. agents were working out their next move: they would put a wire on The Engineer and get him in a room with Alex.

But other questions still gnawed at the F.B.I. men and were soon raised: Why did you warn Ms. Busch? What did you want?

Nothing, insisted The Engineer. He had a daughter about the reporter’s age, and he just didn’t want to see anyone get hurt.

The two agents listened without comment. They didn’t know whether to believe The Engineer, but it didn’t matter. They hurried to call Dan Saunders. By now they, too, were worried about someone’s getting hurt.

Dan Saunders, 41, like so many dreamers before him, had come to Los Angeles hoping to become an actor and a writer. Nearly two decades ago, fresh out of Princeton, he arrived in town with his senior thesis tucked under his arm: a play called The Death of William Shakespeare. After a brief run the play died its own death. Saunders, only a bit daunted, decided that his future was not in pounding out words but rather in speaking them. He had acted at Princeton, always to good notices, and an objective glance in the mirror revealed leading-man good looks—a mop of curly black hair, chiseled jaw, and piercing eyes.

For a while, he had some success, with brooding, if terse, appearances on the network soaps. And he tried the theater clubs, but after too many nights when there were more people onstage than in the audience, as he took to joking, he put his dream aside. He enrolled at U.C. Berkeley’s Boalt Hall law school and landed a fancy job at a Century City law firm. Then, hooked on the drama of trial work, he became a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, assigned to L.A.’s Terrorism and Organized Crime section.

But in the summer of 2002 his life in the shadows was about to end. Dan Saunders was finally about to make it big in Hollywood.

His “break” came when Omellas and Ballard matter-of-factly informed him that The Engineer, a defendant in a fraud case Saunders was prosecuting, wanted to assist in the Busch investigation. Unless Saunders objected, they planned to put a wire on The Engineer and see who would be reeled in.

That sounded like a plan, Saunders agreed. And so it became his case, too.

Over the next two months, The Engineer had several conversations at his home with Alex. His full name, the feds quickly discovered, was Alex Proctor, and he was a short, thin, balding, middle-aged bit player on the bi-coastal drug scene. Before each of these meetings, agents strapped a state-of-the-art digital Kel transmitter to The Engineer’s chest.

There was Proctor, boasting that he had been promised $ 10,000 for the torch job, but when he came up with the scheme to leave the rose and the dead fish instead, people were so pleased that they wiped out an additional four grand he had owed them. “They wanted,” he explained, “to make it look like the Italians were putting the hit on her so it wouldn’t reflect on Seagal.” And that, Proctor told The Engineer with pride, was just what he had inventively done.

The only time Proctor turned cagey was when he discussed his employer. He said Seagal had hired a well-known private investigator who, in turn, had contracted the job out to him. (Seagal denied the charge.) But, to the growing frustration of the men listening to the tapes, Proctor insisted on referring to his boss only as “Anthony.”

As the summer dragged on, however, a glum Proctor began confiding to The Engineer that his boss was having second thoughts about the job he had done. It “didn’t really help,” the private investigator now chastised. “She’s back at it again.” It was around this time that The Engineer, carefully following the script written by the agents, drew Proctor out.

Yeah, Proctor finally said, the “Anthony” who had hired him was private investigator Anthony Pellicano. (Pellicano’s lawyer did not respond to calls for comment.)

Reaching deep into a pile of leaves in a Chicago cemetery, Anthony Pellicano rooted about with an intense, brow-furrowing concentration, and then, with a television camera rolling—presto! He pulled out a plastic bag containing the remains of Mike Todd, Elizabeth Taylor’s third husband. A few days earlier, grave robbers, searching for Todd’s diamond ring, had emptied the coffin. The case of the missing corpse had been solved.

The year was 1977, and with his dramatic abracadabra discovery, just 75 yards from Todd’s vandalized grave, Pellicano, then a Windy City P.I., catapulted himself into the Big Time. The hardscrabble days of skip-tracing department-store deadbeats were over. A grateful Elizabeth Taylor took him under her wing. Next stop—Tinseltown.

There were some who carped that Pellicano’s amazing discovery was just a little too amazing. But, happily for him, in the hubbub of all the ensuing banner headlines, doubts became irrelevant. In keeping with the long-standing Hollywood tradition, one good story is worth a thousand true ones. So after a divorce from wife number three (who had also been wife number two) and moving to L.A. in 1983, Pellicano hooked up with Howard Weitzman, an attorney defending auto mogul John DeLorean against charges of cocaine trafficking. Pellicano’s job was to use his self-taught technical expertise with electronics to analyze and impugn the government’s tapes. When DeLorean was acquitted, Weitzman’s praise was effusive. A star had been born!

This New Age Philip Marlowe, husky, middle-aged, balding, but full of tough-guy swagger, carted boxes filled with high-tech electronic equipment and surrounded himself with a bevy of good-looking, whiz-kid female assistants (Tarita Virtue, one of his in-house “techno-geeks,” as he called them, fetchingly posed in a recent issue of Maxim) as he set up offices in a Sunset Boulevard high-rise. This was the heady role Pellicano had always dreamed of, and now that it was his, he played it with enthusiasm and great devotion. His double-breasted suits and patent-leather shoes were always perfect. His deadeye stare was relentless. And he was great copy. When he gave interviews (was there any publication he didn’t find time for?), there’d be opera booming in his office like a perpetual soundtrack. And, as if speaking dialogue from the inevitable screenplay “inspired by the true story” of his incredible life, he’d hold court. To GQ for example: “If you can’t sit down with a person and reason with them, there is only one thing left and that’s fear.”

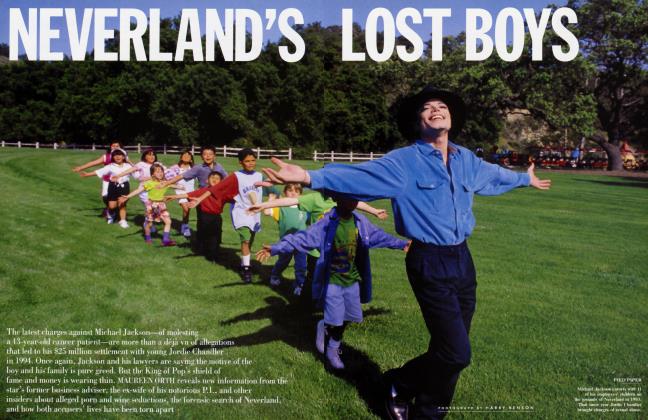

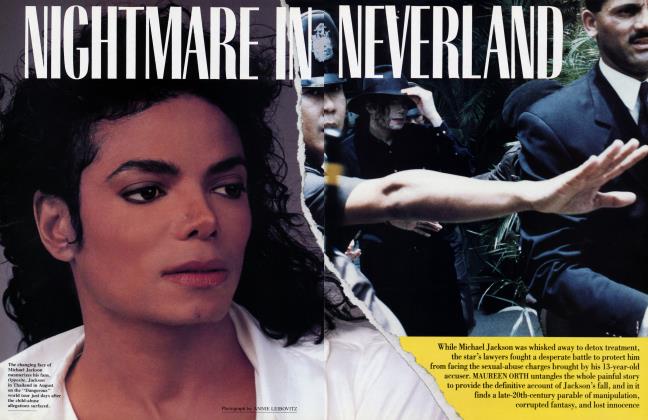

And so the legend grew. If there was a problem, Pellicano was the man who’d fix it. Someone OD’s in producer Don Simpson’s house. A 13-year-old boy accuses Michael Jackson of molestation. Roseanne wants to find the daughter she put up for adoption 18 years ago. The studio exec’s cavorting with hookers. Farrah Fawcett says a boyfriend’s roughing her up. A woman claims Kevin Costner’s been a longtime “friend.” You want the dirt on Schwarzenegger. Who you gonna call? Anthony Pellicano—and then plunk down maybe $25,000 for the initial retainer.

Digging deeper in Pellicano's safe they found more goodies: C-4 plastic explosive, a live blasting cap, and two grenades.

Evidently, Pellicano’s employees and his family were painfully aware of his Godfather fixation. He would tell new clients that they were now part of his family, “and nobody hurts my family.” Kat Pellicano, his newest ex-wife, who is writing a book on Pellicano and his celebrity clients, says, “He should have added ‘nobody but me.’”

In Los Angeles, where people have big problems as well as big money, clients— celebrities, heirs, self-made moguls, and a parade of canny lawyers who facilitate the town’s schemes, dreams, and expensive divorces—kept knocking on his door. And the money kept rolling in. Just from Michael Jackson in 1995, he reportedly pocketed a $1 million fee, another million bucks as a bonus, and a sporty Mercedes convertible as still further reward. Soon the F.B.I. was even hiring him to review tapes. And the long line of anxious clients never seemed to stop. Business was sinsational.

And it took some odd turns. When Michael Ovitz was running his Artists Management Group and found his return to the business of agenting and managing Hollywood talent a little more complicated than he had anticipated, he went to Bert Fields, his attorney. Fields, according to sources familiar with the events, hired Pellicano.

Pellicano, a former employee of his told Vanity Fair, began to wiretap the phones of Ron Burkle, a billionaire grocery tycoon who claimed he was owed money by Ovitz, as well as the phones of two agents who were managing partners at Creative Artists Agency, the talent agency Ovitz had founded and then left.

Burkle, as things worked out, received a tip that Pellicano was tapping his phone and boldly set up a meeting with the detective, according to someone familiar with the events. Pellicano immediately asked the tycoon why Ovitz was after him. When, this source continued, Burkle explained that the attention was motivated by Ovitz’s attempt to renege on the money he owed Burkle, Pellicano burst into an indignant rage.

“I don’t deal in that shit,” Pellicano allegedly said. “When somebody owes somebody money, fuck ’em. They should pay the money! I don’t fuck with my friends’ friends, and I don’t fuck with people who are being extorted out of money owed them. I’m going to tell Ovitz that I’m not going after you. But I’m still going after the two guys from CAA.” (While Ovitz has not returned calls to comment on the allegations, senior members of the CAA managing committee have told Vanity Fair that the agency has had concerns about its phones being monitored.)

There is an interesting footnote to the purported monitoring of Burkle’s phone. Former president Clinton was a frequent houseguest at Burkle’s Los Angeles mansion. Was it possible that Pellicano’s wiretaps had eavesdropped on Clinton’s conversations and that the detective was privy to some of the former president’s secrets? People close to Burkle insist that was not likely. “The Secret Service would have caught it,” one contends. But veteran security experts are less certain. “With Pellicano’s contacts in the telephone company and his very sophisticated software system,” a longtime wireman noted, “it’s more than possible that the feds missed the taps.”

With Pellicano’s success and newfound opportunities, the rest of his life grew complicated. He now had nine children (ranging in age from 14 to 38) from four marriages (to three wives), but he decided that the role of a swinging Hollywood bachelor was more to his liking. When he and Kat, wife number four, divorced, he fled to a luxury condominium in a Mission-style complex on Doheny, just a short walk from his office. And, according to people he worked with, he was often doing his best to persuade many of the sweet, good-looking young “apprentice P.I.’s” he hired to make the stroll back home with him. The Pelican, as he liked his girlfriends to call him, was a very busy bird.

Over the years there were some nasty suspicions about how Pellicano treated people who got in his way, especially pesky journalists. Hillel Levin, a Detroit writer researching a book on DeLorean, was arrested on drug charges that were later dropped after the authorities allowed that he might have been set up. Rod Lurie, in the days when he was a struggling freelancer rather than the in-demand director he’s become (The Contender, The Last Castle), complained that Pellicano persistently tried to intimidate him as he researched a piece about The National Enquirer. Then, after the story ran in Los Angeles Magazine, Lurie was the victim in a hit-and-run accident while bicycling—except he was convinced it was no accident. Diane Dimond, back in 1993, when she was consistently breaking news for Hard Copy concerning the first round of pedophilia charges involving Michael Jackson, was certain her home and private office phones were bugged.

But these were only allegations. The attitude of Pellicano’s many employers was, unless you got something you can prove, go climb back up the Grassy Knoll with the rest of the paranoids. The pragmatic bottom line was that Anthony Pellicano got things done.

Warren Beatty dismissed the inquiry as "complete baloney." "Bert is too smart. He has no need to engage in any illegality."

But that was before Saunders and the F.B.I. agents listened to the tape of Alex Proctor’s incriminating conversation with The Engineer. Suddenly, just how Pellicano got things done was, they suspected, about to become a whole lot clearer.

Armed with a search warrant, a team of F.B.I. agents burst into Pellicano’s offices on November 21, 2002. Straight off he showed them two loaded handguns in a desk drawer. Then he obediently opened the two metal combination safes in the back room. Inside was about $200,000 in cash, the money wrapped in neat $10,000 bundles, as well as what seemed to be a treasure trove of jewelry in boxes and pouches. And, digging deeper, they found more goodies: a cache of C-4 plastic explosive, a live blasting cap, and two U.S. Army Mark 26 grenades that someone had put some effort into enhancing—they were filled with photoflash powder and, if dropped, would fragment and spray shrapnel. The C-4 and the grenades were just the sort of nasty, powerful stuff that could be used, the F.B.I. theorized, to blow up a car. And the explosives were all illegal. Pellicano was arrested that day and faced charges that carried a statutory maximum sentence of 21 years in federal prison.

But the F.B.I. was not done. Anita Busch had been complaining to Ornellas that her phone was bugged, and their interest was further piqued. Another search warrant was issued, and they returned to Pellicano’s office eight days later.

This time they hit the mother lode. Some of what they found was encrypted. Some was already laid out in typed transcripts. Some was on audiotapes. Some was stored on computer hard drives. And many, law-enforcement officials believed, were conversations recorded by illegal wiretaps. There were, these officials estimated, millions of pages!

That’s a lot of secrets.

It was an ingenious operation, and Pellicano apparently had it up and running without a hitch for years. It worked, according to people who were employed at the detective agency, like this:

Pick a target, any target—tinker, tailor, or, say, movie star. First you get his (or, in lots of juicy cases, her) address. No problem there. A police sergeant on Pellicano’s payroll would tap into the L.A.P.D. computer databases. Now that you have the address, getting the phone number is equally easy. A Pacific Bell employee, also on the take, would track it down, along with the coded numbers of the cables servicing the phone.

The rest could have been done either in the central station or, if necessary, at a terminal box. Next to the red and green wires that serviced the line would be a tangle of yellow and black wires—what wiremen call “the spare pair.” Normally, the spare pair is used to hook up an extension or another line. Only, now the yellow and black wires would be, wiremen familiar with the technique theorized, spliced into the main line, and, with the help of some techno-magic, the subject’s phone was a party line—and Pellicano was the one having the party. A phone would ring, say, in a mansion in Bel Air or Brentwood and automatically, silently, simultaneously, computers in his offices on Sunset Boulevard would start taping the conversation. Every move you’d make, every plan you’d make, every vow you’d break, Pellicano would be listening to you.

The case had quickly developed into something larger than Saunders had anticipated. Kevin Lally, another assistant U.S. attorney from the organized-crime section, was brought on to assist him. Lally, in his mid-30s, a three-year veteran in the office, threw himself into the investigation. His father, Gerald Lally, was the general counsel of New York Harbor’s headline-making waterfront-crime commission, and now the son saw this as his opportunity, too.

Saunders and the F.B.I. agents gave this shadow phone network some thought. It could be that Pellicano was simply nosy, a guy who eavesdropped on celebrities for a lot of the same reasons others buy People magazine. Or it could be business— and there’d be no business like selling the secrets of show business. Which quickly raised a potentially even more explosive question: Who was buying? Full of educated suspicions, Saunders decided to convene a grand jury to find out.

“I have been told that I am a subject, not a target, of the investigation,” announced Bert Fields, the L.A. lawyer who is routinely described as “prominent” in decades of press accounts. “But,” he continued in the brief statement issued last November, “I have never in any case had anything to do with illegal wiretapping.”

Yet despite Fields’s careful parsing—“subject” is a pretty broad and open-ended legal term that, like a film’s being “in development,” carries no guarantee that anything significant will ever come to pass— his words hit Hollywood with the bang! of, well, one of Pellicano’s fragmentation grenades. It was confirmation that the federal grand jury was interviewing the well-known lawyers who had employed the detective to shore up the prospects of their even better-known clients.

According to legal sources familiar with the grand jury’s probe, the government has been tenaciously circling several of Fields’s cases. Questions have been asked about his defense of manager-producer Brad Grey (whose enormously successful career includes representation of Brad Pitt and Adam Sandler) in suits filed by actor-comedian Garry Shandling and producer Bo Zenga, as well as a bitter divorce in which Fields’s firm represented Leonard Green (who before his recent death had been the founder of a large leveraged-buyout company), and a defense of Taylor Thomson, a member of the Canadian newspaper family, against charges from a former nanny alleging she was wrongfully dismissed.

In reviewing these cases, prosecutors have asked several of the litigants if they had reason to believe they were wiretapped, or if they had any knowledge of illegal eavesdropping.

While the grand-jury proceedings remain secret, there was, according to a lawyer familiar with the inquiry, testimony that Shandling was warned soon after he filed his suit that his phones were tapped and he should use only a cell phone. A security expert also testified at a deposition, “It is pro forma for you to advise clients to conduct sweeps of their telephones in any matter in which Bert Fields is involved as the opposing counsel.”

Bo Zenga—who lost his initial lawsuit against Brillstein-Grey Entertainment claiming that an unwritten producing agreement for 2000’s Scary Movie had been ignored, and then, in a ruling that pointedly attacked his credibility, lost the appeal—was another individual who testified before the grand jury. “The topics covered,” he told the Los Angeles Times, “were wiretapping and the intimidation of witnesses in my case with Brad Grey.” He also said he planned to appeal the ruling to the California Supreme Court, but so far he has not filed.

Pellicano told clients they were family, "and nobody hurts my family." "He should have added ‘nobody but me,'" says an ex-wife.

Grey, in a statement to The New York Times, said, “I can’t imagine Bert Fields would be involved or get his clients involved in anything like this. I never heard anything about any wiretapping, and that’s what I shared with investigators when they asked.”

Other of Fields’s famous clients were similarly supportive. Warren Beatty dismissed the inquiry as “complete baloney.” “Bert,” he went on in a measured, deliberate voice in a recent telephone interview, “is too smart. He has no need to engage in any illegality to get an advantage.” And Jeffrey Katzenberg, for whom Fields won a reported settlement of more than $200 million in his contract dispute with Disney, made a particularly persuasive defense. “I worked with Bert seven days a week over five years in a case that was arguably the biggest, most high-profile case of his career, and not once did he ever suggest doing anything that would be playing outside the rules.”

Fields has not been charged with any wrongdoing. And, as he stated in a letter to the court supporting Pellicano’s release on bail after his arrest, the lawyer is unaware of any misconduct by the detective. Fields wrote: “I have known and worked with Anthony Pellicano for nearly 20 years. My firm has hired Mr. Pellicano as an investigator for dozens of cases, many of which I have personally handled. I have never once known Mr. Pellicano to commit an act of violence. He has been thoroughly professional in all my contacts with him.”

But might Pellicano have provided an unsuspecting Fields with tainted information? Could the lawyer have been unaware of how the private eye got the dirt? In response to these and other questions, John Keker, Fields’s attorney, issued the following statement to Vanity Fair: “Bert Fields has never asked for; used, received, or condoned the use of wiretap information. He is not the target of any investigation.” Pellicano told the Los Angeles Times, “My clients and the lawyers who hired me are completely innocent.”

Neither Mr. Fields nor his lawyer would elaborate on their statement. Therefore, in this vacuum, insights from other sources will have to do.

Possibly worth scrutiny, then, are Fields’s novels, written under the pen name D. Kincaid, sexy page-turners featuring attorney Harry Cain. “He is,” the jacket copy of one breathlessly promises, “Los Angeles’ legendary courtroom ‘bomber,’ friend, enemy, confidant and interrogator of the rich and famous.” Sound familiar? But while Flaubert conceded, “Madame Bovary, c’est moi,” Fields is no Flaubert. It would be wrong, a foolish stretch even, to say Cain is Fields.

Nevertheless, Cain’s relationship with his fictive private eye, Skip Corrigan, makes interesting reading. When, for example, Corrigan reports that someone threatening to sue one of the lawyer’s clients is making dirty phone calls to a lady friend who “got one of those black-leather bikini outfits with the chains, you know,” the detective cuts the lawyer off before he can probe. “Don’t ask me how I know. u don’t wanna know.” And when a randy Cain wants to track down the home of the bombshell who brags that “my hobby is fellatio with strange men,” he simply asks Skip to run the license-plate number. The detective, without further elucidation of his methods, gets the address.

Did Fields work with Pellicano in a similar don’t-ask, don’t-tell manner? This is one of the questions to which the grand jury, in its own, more probing way, is trying to find answers.

Meanwhile, the government’s investigation continues. And it’s not just Fields who is the recipient of the government’s attention. Investigators are reviewing the conduct of many in the crowd of lawyers who employed Pellicano and are looking at dozens of previously adjudicated cases. Ornellas, Ballard, and their squad are conducting interviews and tracking down evidence. Dan Saunders is still calling witnesses to testify before the grand jury. And, most daunting of all, federal prosecutors, headphones tight on their heads day after long day, are listening to hours and hours and hours of tapes, sifting through the mundane, the irrelevant, and the dirt for clues. Nevertheless, people close to the investigation assert confidentially that there will be more indictments. And these law-enforcement sources also predict that there will be more lawsuits: civil suits challenging multi-million-dollar awards and settlements in cases where, it will be alleged, litigants had the advantage afforded by illegally obtained information; suits against the city of Los Angeles asserting misconduct by police officers who allegedly sold confidential information to Pellicano, who in turn shared it, whether knowingly or unknowingly, with lawyers; and suits against Pacific Bell for not adequately protecting the security of its phone lines. It will be a very public morass of sticky and embarrassing litigation, and reputations as well as tens of millions of dollars will be at stake.

On Sunset Boulevard, Pellicano’s name has been removed from the door of the offices he rented. The suite, once booming with arias as its furtive banks of computers allegedly recorded conversations on phone lines throughout the city, is quiet and empty: a cave of secrets. His staff has moved on to other jobs. Five of them, however, have been given limited immunity from prosecution and are cooperating with the federal investigation. Bursting with anxiety, one of his former “techno-geeks” told Vanity Fair, “This is huge-I had been in hiding. The F.B.I. made me leave town. I am a pivotal part of this and must watch my ass. I have a gun in my home. My house has been damaged_He called my parents ... and said, ‘I know your daughter’s testifying and that’s a damn shame.’ That’s when the F.B.I. told me to leave. I went to live with my bodyguard.”

As for Anita Busch, it’s closing in on two years, and she’s still waiting for the people who allegedly ordered Proctor to torch her car to be caught. Both Pellicano and Seagal have denied responsibility. Nevertheless, she remains confident that “Stan Ornellas will get his man.” Busch refused to comment further on the story other than to say, “I’m concerned, but not discouraged.”

Pellicano also appears not to be discouraged. In the midst of his trial last fall, he pleaded guilty to illegal possession of explosives and then asked to start serving his time. Under the plea agreement, the sentence will be a relatively light one. (It had not been set precisely as of press time.)

On the weekend before Pellicano went to prison, he married his fifth wife in a ceremony in the small chapel of Las Vegas’s Bellagio Hotel. The bride, Teresa Ann DeLucio, a 42-year-old former Chicago bar dancer, was dressed in a long, white V-necked gown. The 59-year-old groom wore a dark, pin-striped double-breasted suit. And, it was observed, a big smile.

It was perhaps only a coincidence that earlier in the week investigators had learned that Pellicano allegedly had filing cabinets hidden away that were crammed with tapes. And that many of these tapes were secretly recorded conversations between him and the lawyers with whom he had worked so closely for so many years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now