Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThree years after Phil Spector was charged with the murder of B-movie blonde Lana Clarkson, his trial is postponed yet again. The author also gets a sordid update on another celebrity defendant, O. J. Simpson

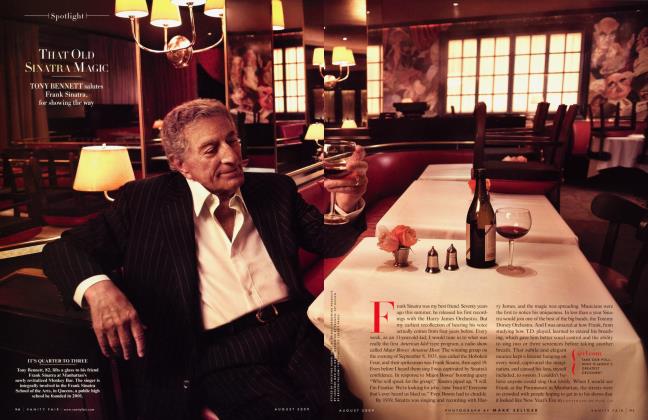

July 2006 Dominick Dunne Mark SeligerThree years after Phil Spector was charged with the murder of B-movie blonde Lana Clarkson, his trial is postponed yet again. The author also gets a sordid update on another celebrity defendant, O. J. Simpson

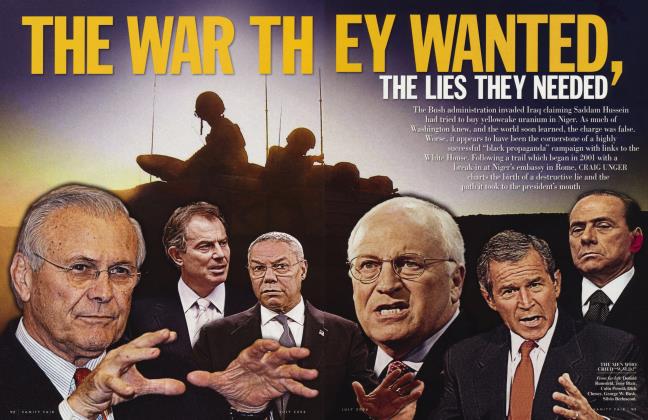

July 2006 Dominick Dunne Mark SeligerImagine running into a former covert C.I.A. operative on Fifth Avenue. One of the many wonderful things about living in New York is having surprise encounters on the street. It was a beautiful spring day. The sidewalks were crowded. I was racing up Fifth Avenue, because I was a little late for a lunch date at Michael's, on West 55th Street, when I heard someone say my name. I slowed down, turned around, and saw a familiar face I could not immediately identify, until he reached out his hand and said, "Joseph Wilson." It was the former ambassador, whose op-ed article in The New York Times on July 6, 2003, entitled "What I Didn't Find in Africa," asserted that the administration had twisted intelligence reports about Saddam Hussein's efforts to obtain uranium in Niger in order to build nuclear weapons. The article so infuriated those in the White House that they allegedly authorized Vice President Cheney's chief of staff, Scooter Libby, to disclose the fact that Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, was a C.I.A. operative.

"This is my wife," said the ambassador, and there was Valerie Plame, the outed operative whose name had been on the front pages of newspapers on and off for three years. New York Times reporter Judith Miller went to prison for 85 days for refusing a court order to answer grand-jury questions on the subject, although she never wrote about Plame. Matt Cooper, of Time magazine, almost went to jail, too. Syndicated columnist Robert Novak was the first person to reveal Plame's name, but he suffered little consequence. Libby was indicted for perjury and obstruction of justice, and has a trial coming up.

"Oh, my God," I said. I'd only seen pictures of Plame. She is very pretty, and she was smiling and friendly. "Karl Rove was called before the grand jury today, for the fifth time," said the ambassador, referring to President Bush's chief political adviser. After a few moments I said, "Congratulations on what you wrote." Then I kissed the no-longer-covert operative, and we went our separate ways. But New York turns out to be a very small town. An hour later, they appeared at Michael's, and that night they turned up at the big dinner given by Graydon Carter and Robert De Niro at the State Supreme Court building in downtown Manhattan to kick off the Tribeca Film Festival. By that time, I felt we were old friends. Plame, wearing a light-blue strapless evening dress, got more attention than a movie star.

The film festival, which is run by De Niro and Jane Rosenthal, took a big chance by opening with United 93 at the Ziegfeld Theatre. I had no real inclination to see it, because I didn't want to put myself through the ordeal of watching a re-enactment of the tragic 9/11 crash. But when Peggy Siegal, the Perle Mesta of media society, hones in on you to attend one of her events, you have no choice but to accept, and I'm very grateful that I did. It was a premiere, with a fleet of photographers flashing away, but the crowd was subdued, for we all knew what we were in for. Inside, many relatives of the 40 victims were seated in a block at the rear of the theater. When Jane Rosenthal announced their presence, the entire audience rose from their seats, turned around, and applauded them. It was an unbearably sad moment. After the film, I talked with several family members, who, although devastated by what they had seen, said they were glad that it had been made. I can't remember when a film has affected me as much.

I am not one of those people who say, "I happened to glance at The National Enquirer in the checkout line at the A&P today," and then proceed to discuss the leading scandal of the moment with a certain degree of embarrassment. I almost never miss The National Enquirer, and if I had known it was available by subscription, I would have taken one out years ago. One thing I learned during the time I spent in Los Angeles covering the lengthy O. J. Simpson murder trial in 1995 was that this often maligned tabloid is remarkably accurate in its sensational revelations. The paper's coverage of many areas of the Simpson case was positively breathtaking. Though many of us in the press would say in an arch, dismissive voice, "But they pay for their information," we all pretty much devoured every word. The general assumption among us was that the Enquirer had to have some of the best libel lawyers in the country vetting the stories it dared to print.

At one point a rival tabloid played an offstage role in the trial. The only person alleged to have seen O.J. driving near Nicole Brown Simpson's condominium on Bundy Drive the night the double murders occurred was scheduled to be a witness for the prosecution. However, after the individual sold her story to the TV show Hard Copy and the Star, Marcia Clark, the chief prosecuting attorney, disdained to put her on the stand, as if her transactions with the tabloids had made her unworthy to testify.

In the years since Simpson's quick acquittal at the end of the criminal trial stunned the nation, the Enquirer has been vigilant in reporting each and every seamy episode of his life, including the problems he had with his daughter, Sydney, in 2003, when she called 911 and asked the Florida police to rescue her from her father's house, and various tacky romps he had with blonde Nicole look-alikes. In May he was on the cover of the tabloid once again, in a story about a cheap and tawdry incident involving a reported overdose he had suffered in a Miami apartment during a marijuana-cocaine-and-Ecstasy binge. His girlfriend Christine Prody and another woman were reportedly also present. Simpson has allegedly always been a big drugger. As I reported in 1995 during the trial, a lookout man for a drug dealer came to my room at the Chateau Marmont to tell me he and the dealer had sold crystal meth to O.J. in Simpson's Bentley in the parking lot of a hamburger joint early on the night of the murders. The man claimed to have passed a lie-detector test and said he wanted to be a witness for the prosecution, but the nature of his work deprived him of credibility.

In the recent article, Simpson, stoned and sweating profusely, and not wanting to go to a hospital for fear of having to face reporters, is quoted as saying, "I'm freaking myself out." Thereupon, the other woman present split, and Simpson allegedly began talking to his girlfriend about the murders: "Maybe I did kill Nicole. If I was on the jury, I'd have voted to convict. That's for sure." That Simpson would actually say that about Nicole seems to me very improbable, but there has never been a doubt in my mind that he was guilty. The second jury he faced, in 1997, in the civil suit brought by the families of Nicole and the other victim, Ronald Goldman, felt the same. In the nine years since then, The National Enquirer, in its own persistent way, has kept showing us what life after an acquittal such as Simpson's must be like.

If you are charged with murder in a high-profile case, the best thing your defense attorney can do is keep getting your trial postponed, until the memory of the victim fades and you become the center of interest. The frequently delayed murder trial of the early rock 'n' roll legend Phil Spector, 66, has recently been put off yet again, until January 16, 2007, which will be a month shy of the fourth anniversary of Lana Clarkson's death. Clarkson, a beautiful, blonde, 40-year-old B-movie actress, who was doing temporary work as the hostess of the V.I.P. room at the House of Blues on the Sunset Strip, was killed on the night of February 3, 2003. An intoxicated Spector had picked her up, after being seated by her in the club, and had whisked her off in his chauffeur-driven Mercedes to his mock castle, in Alhambra, California, 20 minutes from Los Angeles. An hour later she was dead, with a single gunshot in her mouth. Her publicist, Edward Lozzi, described her to me in this way: "She was an astounding beauty who could impress the ladies who lunch at Spago and at the same time she could ride a saddle-less horse in a loincloth at full gallop while shooting a crossbow with uncanny precision."

Spector, who was charged with Clarkson's murder, has not spent a night in jail. Robert Shapiro, the first of his three lawyers and also his friend, got him freed on $1 million bail. Spector had to surrender his passport, but he was excused from wearing an electronic ankle bracelet. A bizarre-looking figure, he continues to dine at such "in" restaurants as Dan Tana's, in West Hollywood—one of his early stops on the night he met Clarkson. I have seen him out once, at the fashionable Dolce Vita, in Beverly Hills, in the company of a blonde beauty in the 40-year-old range. The other diners were silent as the couple passed through the restaurant.

No one has given much credence to Spector's story that Clarkson committed suicide. The trial was due to start April 24, but Spector's lawyer, Bruce Cutler, often described as mobster John Gotti's lawyer, became involved in the "Mafia cops" trial in New York. Spector's trial was then scheduled for September, and it has now been postponed until January.

I can't remember when a film has affected me as much as United 93.

In a surprising development, Cutler's client Louis J. Eppolito, a retired New York detective who was convicted of "helping" in at least eight murders by the Mob, has fired his formidable lawyer and accused him of doing shoddy work, asserting that Cutler botched the job, and that his whole defense was incompetent. Cutler called Eppolito "a desperate man in desperate times," and stands by his work. A hearing on the matter is scheduled for late June.

In the meantime, Spector has other worries in his troubled life. He recently lost a bid to delay court proceedings on a lawsuit involving his former personal assistant until his murder trial is complete. Spector sued the former assistant, alleging that she had stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars from him. The assistant countersued for $5 million, charging, among other things, sexual harassment. That sort of publicity is not going to help Spector when the trial for the murder of Lana Clarkson begins.

From the time I was a little kid, I have been fascinated by movie stars. My older brother, Richard, with whom I shared a room growing up, had pictures of baseball stars on his side of the room, and I had pictures of movie stars on mine. Even at 80, I still get a little weak in the knees when I meet a very special one. It happened recently when Liz Smith, the gossip columnist, asked me to join her at lunch at Michael's with the great Helen Mirren, who was briefly in New York for the publicity launch of Elizabeth I, her superb two-part film on HBO, which was to be screened that evening before some of the biggest names in New York. I wasn't actually meeting Mirren for the first time. During the O. J. Simpson trial I sometimes saw her at the late actor Roddy McDowall's movie-star dinner parties with her film-director husband, Taylor Hackford, but I never had a real conversation with her.

I was a little late arriving. The two ladies were already seated at Table No. 4, the best table in the house, always reserved for the biggest name in the room. Even before I got to the table, I saw a few important people line up, like supplicants at the court of Elizabeth I, to pay homage to her. The fact is, she is rather queenly, in the friendliest kind of way. We did a little dishing about Hollywood friends. She talked with great fondness of Jeremy Irons, who plays the Earl of Leicester, the passionate lover of Elizabeth's middle years, and of Hugh Dancy, who plays the very young Earl of Essex, the passionate lover of her older years. Mirren has let it be known that she firmly believes the Virgin Queen was no virgin, and she acts the role accordingly. You can feel her lust for her handsome lovers. Mirren talked about her elaborate costumes, her jewels, her wigs, the hours of preparation to get ready to shoot. She gives a simply staggering performance, a worthy successor to Bette Davis and Glenda Jackson, who both played Elizabeth in earlier film incarnations. She had also just finished a new project in England, playing Queen Elizabeth II. The entire action is limited to the days following Princess Diana's death, when some members of the royal family did not immediately respond to the national tragedy, remaining too long at Balmoral rather than returning to London.

Mirren was here only for the P.R. screening of Elizabeth I and was then on the next plane back to England, where she is shooting the next episode of her immensely popular series, Prime Suspect. When she comes back, she's going to live in New York. She and Taylor Hackford have just built a penthouse on a downtown building.

For correction of certain inaccuracies concerning Manhattan antiques dealer Helen Fioratti in my April Diary, see page 32 of the Letters column.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now