Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Book of French Verses

Some of the Little Known Work of Charles Cros

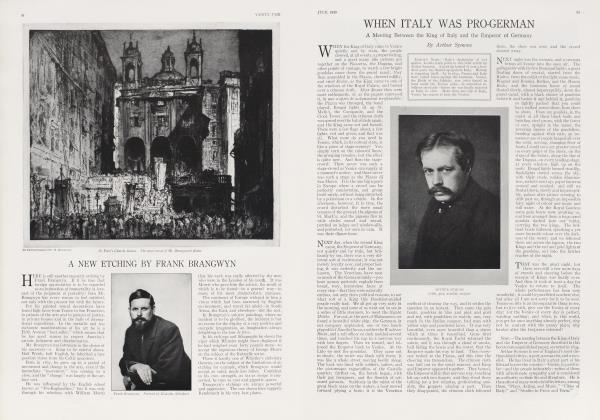

ARTHUR SYMONS

YEARS ago, when I was in Paris, and used to go and see Verlaine every week in his hospital, I remember he burst out suddenly one clay into eulogies of Charles Cros, and asked me if I had ever read "Le Coffret de Santal." On my saying no, he urged me to read it, and began to speak, in his generous way, of what it seemed to him he had learnt from that poet of one book. It was a good while before I succeeded in finding a copy; but at last I got it, and read it, I remember, at that time, with an enchantment which I cannot entirely recapture as I turn over the pages again to-day.

Not long afterwards I was at a literary house, and I overheard someone being addressed as Dr. Cros. I asked him if he was related to Charles Cros; his brother, he told me. Finding me enthusiastic, he talked freely, giving me quite a new idea of Charles Cros as a man of science, I believe the discoverer of something or other, as well as a fantastic poet. Dr. Cros told me that his brother had left a number of MS. poems, at his death in 1888; that they were in his own possession, that he would be glad to publish them, but that Charles Cros was so little known that no publisher could be found to undertake the publication. I promised to write something about "Le Coffret de Santal," but, other things coming in the way, I wrote nothing. I had almost lost sight of the man and his book, when, as I was in Paris on my way back from Spain, I was unexpectedly reminded* of my promise. I was talking with Yvette Guilbert, whose knowledge of French literature has often surprised me; but I was never more surprised than when she said, a propos of nothing at all: "Why have you never translated anything from Charles Cros—you, who have translated so many things from Verlaine?" "But do you know Charles Cros?" I said, forgetting to conceal my surprise. "But I adore him," she said, and began to quote his verses. I promised to„translate one of his poems. To-day it occurs to me to keep both my promises.

WELL, as I turn out this "Sandalwood Casket," full of bibelots d'emplois incertains, made out of sourires, fleurs, baisers, essences, I seem to find myself at that moment in French literature when the Parnasse was becoming not less artificially naive and perverse at once. It belongs to the period of Les Amours Jaunes of Tristan Cor bier e and the Rimes de Joie of Theodore Hannon, both of which you will find praised and defined in Huysmans' A Rebours; but it is more genuine, and more genuinely poetical, than either. Learning much from Gautier in his form, from Baudelaire for his atmosphere, and, more than from either, from the popular songs of many countries, he seems to anticipate Verlaine in

Des Choses absurdes vraiment, metre and sentiment. And yet he has still the habit of writing in which boats had

Mat de nacre et voile en satin, Rames d'ivoire.

He seems at times to be accepting every commonplace of poetry, but the commonplaces turn diaphanous under his touch, and come to us with little pallid, pathetic graces, like toys in tears, or as if Dresden china shepherdesses had begun to weep.

Ma Belle amie est morte Et voild qu'on la porte En terre, ce matin,

En souliers de satin.

It is all poetry made up by one who has lived a faint, scarcely passionate, over-dainty life avec les fleurs, avec les femmes. You might be deceived into thinking him more real, or more unreal, than he is.

Ce n'est plus I'heure des tendresses Jalouses,'ni des faux serments, but of a kind of remembering tenderness, in which there is something of the senses, something of chaste ideals, and more self-pity than really poignant sorrow. The poem called Lento, perhaps the best poem in the volume, is wonderfully touching, as it murmurs almost sobbingly in one's ear, going on to an effect really of slow music, in its delicate, returning cadences. It gives us, in its evasive, whimsically ironical way, a sort of philosophy of just these perfumed sensations which can so easily turn painful or overpowering.

Mais il ne faut pas croire a I'ame des contours,

it cries, with a child's surprise; and it is with a darker, more macabre sense of the soiling mystery of death, and the end of beauty, that a poem called "Wasted Words," which I have translated for a specimen, sums up the attitude of the universe towards woman and of woman towards the universe:—

After the bath the chambermaid

Combs out your hair. ' The peignoir falls

In pleated folds. You turn your head To hear the mirror's madrigals.

Does not the mirror's voice remind Your pride: "This body, fair in vain, Decrepit shelter of a kind Of soul, must find the dust again.

Then shall the delicate flesh forsake The bones it veiled; and worms intrude

Where all is emptiness, and make . A busy nest in solitude."

You listen with a soulless smile,

Too proud to heed the things they say;

For woman mocks at time, the while To-morrow feeds on yesterday.

Baudelaire has taught all modern poets the suggestive value of perfumes, but no one has ever used them with such constant and elaborate felicity. Exotic always, now Chinese, now Ethiopian, now gipsy, now the discord of a night of insomnia, now the penetrating, unreal harmony of a hasheesh dream, perfumes steam up out of all these pages by Charles Cros; yes, even natural perfumes, out .of the hayfields and hedges of the real country. For Cros is not so morbid as one is at first inclined to suppose.

TS it really with any sincerity that he says: Je me tue a vouloir me civiliser I'ame? And is all this Parisian exotism really a kind of revenge of nature upon one not naturally, or not exclusively, limited to what is most like the bibelot in humanity? At all events, here, in the midst of these tender, and fantastic, and pathetic sentimentalities, are the delightfully humorous Grains de Sel, which one should have heard their writer sing for the full enjoyment of them; the Hareng Saur, which has a little immortality of its own, among people hardly aware whom it is by; the Chanson des Sculpteurs, which sums up Montmartre; and the Brave Homme, which anticipates Aristide Bruant.

A set of fifteen dizains parodies Coppee, doing his "Annals of the Poor" better than he could do them. It was the time of paradoxes when this book was written; it has indeed always been very French, and in every time very modem, to have irony or humor for a part of one's equipment as a poet; and Charles Cros is very French, and in his own time was very modern.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now