Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Invasion of Germany

Shall This Become a Part of the Allied Strategy in 1919?

J. B. W. GARDINER

GENERAL PEYTON C. MARCH, our Chief of the General Staff, has told us that, if we give him 80 divisions of Americans (an American division consists of 40,000 men) in France by next June, the war will end in 1919.

There is, moreover, excellent reason for believing that by June of next year we will have these 80 divisions in France, and that shipping will be available both to take these men to Europe and to keep up the necessary flow of supplies for them.

It is therefore safe to assume, as a starting point, that next June will see 3,000,000 Americans in France ready to enter the fighting.

What, then, will be the relative strength in man power of the Allies, as compared with that of the Teutonic Powers?

We may disregard, entirely, Austria, Bulgaria, and Turkey. The Italian army has shown itself thoroughly capable of neutralizing Austria; the combined Allies before Saloniki, and the British in the near east, offset Germany's Balkan Allies.

THE situation, then, narrows down to the question of Germany against England, France, and the United States. The maximum force of actual fighting men which Germany can put in the fi^ld for the 1919 campaign is under 3,250,000 soldiers. Of this force about 500,000 must be kept in Russia, scattered over the territory which Germany has overrun, in order to guard the loot she has acquired. There will, therefore, be available for service in France 2,750,000 German soldiers. This figure is reached by assuming that the accretions to German strength before the spring of 1919 will equal her losses since March 21st.

Against this force France and England can feadily place an army of over 3,000,Q00 men, so that, at the very least calculation, the Allied numbers will exceed those of Germany by the strength which America is able to put into the field.

This force of ours, then, of 3,000,000 men, is the strength of the striking force of the Allies. This is the force with which General March says the war will be ended in 1919. No man can foretell how the end will be brought about; what the various military steps will be, or where the main attack will be launched. There are, however, certain essential facts which we must recognize and certain probabilities we may consider.

First, what do we mean by winning the war? No man, who is loyal to America, can interpret this phrase to mean aught but a military decision. Germany must be beaten by force of arms; her army must be destroyed, captured, or dispersed;, there must be an absolute and unconditional surrender. This is what the situation demands, not only in the eyes of our soldiers, but in the eyes of all civilians who treasure life, liberty, and a permanent peace.

IT is from this standpoint, then, that the next year's campaign will be discussed. On this basis we may go one step further. No military decision is likely to be reached until the war is carried into Germany; until the people of Rhineland, of Westphalia, of Prussia, have visited upon them some measure of the horrors which have been inflicted upon the populations of France and Belgium. Their cities must be racked, and tom with shell fire, until only gaunt, ragged and tottering walls mark the places where buildings once stood. Until the German people, prostrate, feel the heel of the war-god whom they have so long worshipped, tearing their flesh and crushing their lives, then and then only, will they know the horrors which war brings, and then only will they make peace.

It is not improbable that before 1918 has passed by, the Germans will be back in the positions they occupied at the beginning of the year, that is, the old Hindenburg line. This, then, must be our starting point. By striking, head on, against that line we may succeed in driving the Germans back, step by step, until they are in their own country. But this could hardly be done in a year's fighting. Behind the Hindenburg line there is practically a continuous series of parallel trenches, all the way to the German frontier. The Allies then would be continuously attacking strongly fortified positions. Our loss in men would be terrific, and the results questionable.

While all of occupied France and Belgium might be redeemed, the German army would still be intact. It is, moreover, almost impossible to invade Germany by an attack from the north or west. Such an invasion would have to follow the route pursued by Germany in 1914. This is not possible in the face of continuous and organized resistance.

Germany, as we know, came down between the frontiers of the Netherlands and Luxembourg and struck the Belgians at Liege, the right following the Sambre River to Namur, the centre coming through Luxembourg. Luxembourg is very mountainous; it is full of strong positions the forcing of which by frontal attacks would be almost impossible. North of Luxembourg the French and Belgian Ardennes are not only equally difficult terrain, but their western border is guarded by the lower reaches of the Meuse River, which is a most formidable military obstacle. The only open country is between the northern Ardennes and the Dutch border. But, even this, too, is guarded by the Meuse. When it is realized how difficult it has been to force the passage of even the smaller streams of France, the practical impossibility of driving across such a stream as the lower Meuse becomes at once apparent.

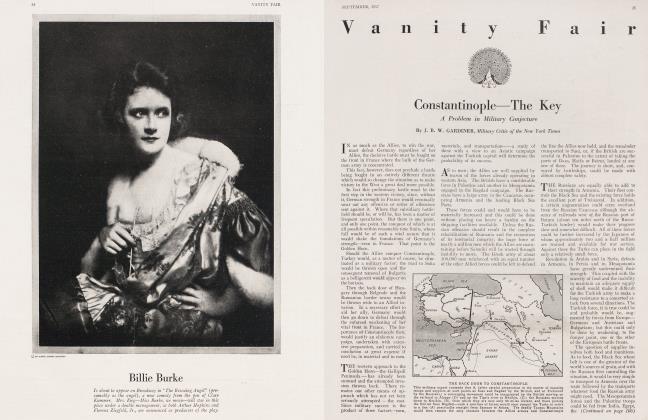

There are thus eliminated two possibilities— one an attack from the west against the gateway to northern Germany; and one an attack from the south, by way of Verdun. There remains, then, only the possibility of reaching Germany by striking north and west from the front between Verdun and the Swiss frontier.

THE first step, on the northern section of this line, would be to take Metz as a base for further operations. From Verdun to St. Mihiel the French line runs along the eastern border of the Meuse heights and overlooks all of the broad Woevre plain, east of the Meuse. Between St. Mihiel and Pont-a-Mousson the lines are on the heights of Lorraine, from which the southern fortresses of Metz, nestling down in the valley of the Moselle, can already be reached by the French artillery. The first step would then be an advance against Metz from both directions. This advance might indeed be continued down the valley of the Moselle through Lorraine, but, because of thq rugged character of the country, this would be a dubious undertaking.

Simultaneously with the movement against Metz would come an invasion of Alsace with the object of reaching the Rhine and obtaining control of the Rhine valley. This valley is. screened, from the west, by the Vosges Mountains, which can be crossed by a military force only in a few places. The barrier is not wide,, however, and the French are already across it in certain places. In fact, between Colmar and Mulhausen they are almost down in the valley. It is probable that all of the Vosges, passes would have to be stormed simultaneously by the Allies so that the offensive will extend from Verdun to the Swiss frontier. Success here would give the Allies the west bank of the Rhine from Strassburg to the Swiss frontier.

Continued on page 110

Continued front page 43

Before Strassburg is reached, however, the Germans in France and Belgium will see the threat to their main bases hundreds of miles in their rear, the vision of being completely cut off from supplies, every line of communication endangered, and will begin a hurried retreat. But the moment this retreat begins, serious trouble will develop for the Huns. The task before them of drawing their army out of France is stupendous enough, but when this army is being vigorously pressed by a force including 3,000,000 Americans, it is likely to be overtaken by some dire disaster.

IF the Allies invade Germany, then, there is every probability that the route followed will be the Rhine valley, the line being gradually pushed north until the two opposing armies face each other on opposite sides of the Rhine. The question then arises, what will the Allies do? If the German army makes good, even in a reasonable degree, its retreat to the Rhine, will the Allies be able to force the river and penetrate into interior Germany? In all probability it cannot be done. But, on the other hand, it will not be necessary. The keystone of the arch of German military strength is found, first, in the iron mines of Lorraine, of the Brie basin, and of Belgium; and, secondly, in the coal mines of France and of Belgium. Take these away and the arch would collapse of its own weight. The war would end in a German surrender, because of her failure to secure material with which to wage it longer.

BECAUSE Germany cannot wage this war, or any other war, without these mineral storehouses, this war must go on, regardless of cost, until they are taken from her; and, once taken from her, the future peace of the world demands that they be never returned but placed in the hands of the gentlemen among nations who, having power, can still use it without abusing it. For this is the distinguishing mark between civilized men and the wild beasts we are engaged in fighting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now