Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLiterary Close-Ups

II. Joseph Conrad: A Pen Portrait by a Friendly Hand

HUGH WALPOLE

I WAS talking to a man the other day who was just going to see Joseph Conrad. He confessed to me that he was frightened. I asked him where his terror lay, because he was a man of supreme self-confidence and liked to declare that "he was quite as good as anybody".

"Well" he said, "it's this way. With most men you know where you are, beforehand. A fellow's an artist, or he's a cab-driver, or he's a banker. There you are. You talk about pictures, or cabs, or money. You're safe. But when you're going to see someone who's a Pole, and a captain in the merchant service, and writes better English prose than any living Englishman—well, you're done. He can have you—anywhere."

"You're thinking too much about yourself", I said. "You needn't worry. Conrad's the most courteous man in Europe."

I believe that my friend fared very well. He is a brilliant talker, and kindly, and Conrad values kindliness, I think, beyond almost any other gift. Nevertheless, the puzzle of all those contradictions remains.

A very considerable number of years ago, after the publication of his first book in, I fancy, 1894, Conrad left the sea and planted himself in the middle of Kent; there he has remained planted ever since.

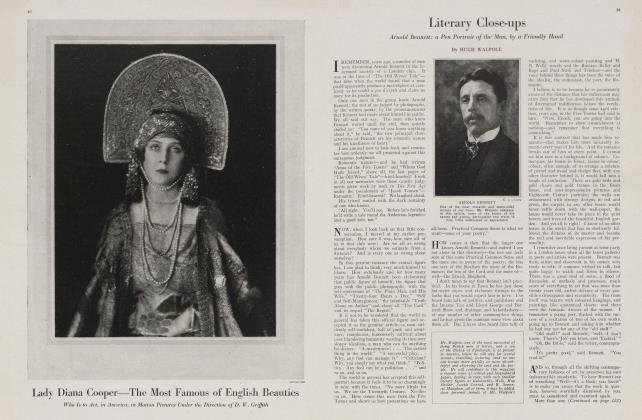

A Picture of Conrad

WHEN I think of him I see him, in my mind's eye, spare, short, squareshouldered, his grey bear'd fiercely peaked, his billy-cock hat a little on one side, his eyes kindly, humorous, and penetrating; sitting in the middle of the Kentish fields, quite ready to sit there until the end of time, granted that his wife and sons will sit there with him, having travelled, he will give you to understand, enough in his first thirty years to earn his everlasting right to motionless, passionate observation.

It is true enough that he likes to break his immobility with sudden flashes of passion, or humour, or interpretation of life, but these flashes are as swift and transient as lightning on a summer sky. They only emphasize the tranquility the more. Nor do I think that I see him as covered by any especially gorgeous edifice. A roof and four walls is enough for him. Not that he does not care for comfort, but the comfort that will satisfy him is more easily attained than the ordinary man's comfort. His complaints at the narrowness of a room, the dampness of a wall, are vociferous enough: nevertheless the great point is that he should be allowed to'remain in the Kentish fields where he can hear the voices of the Kentish people, and see the soft clouds of the Kentish sky, the dim blue of the Kentish horizons.

He found, nearly thirty years ago, the Spot of all the earth where he wishes to be and to that spot he will be faithful. He has the same simple unswerving fidelity to people. He once had a dispute, with a friend. "There is a fundamental difference between us," he said, " You don't love men but believe that they are to be improved. I know that they are not to be improved— but I love them." That may stand as the motto for his life and his work.

Talk of millenniums infuriates him.

He believes that human nature will remain the same to the end of time, fallible, ignorant, courageous, touching, childish, noble. He believes in the courage of the individual in his fight against almost overwhelming odds—and he does not wish the odds to be less overwhelming.

The Mystery of Conrad

THIS, at least, seems to be the philosophy behind all his books, the philosophy in his talk and his daily life. I don't pretend that the definition of it is more than a fallible man's assertion.

And yet when one has stayed with him, when one has seen the simplicity of his life, the happiness that radiates from his wife's great personality, when one has played billiards and tennis, and driven in the motor-car, and taken snap-shots, and laughed and joked, and done all the silly, happy things that anyone does in any country-house, the mystery remains.

There is the mystery first of the man himself—the mystery that the son of a Polish nobleman should run away to sea, learn English from old files of the 'Standard' newspapers when he was thirty, toss about the world as an English seaman, finally share with Thomas Hardy the title of the greatest living English novelist— what kind of man can this be?

Secondly, there is the mystery of his books. One is haunted, in Conrad's old Kentish house, by the ghosts of those men and women whom he has created— by the broken Almayer; the glittering courageous braggadocio Nostromo; by the sinister nigger of the 'Narcissus'; by Verloc, the secret agent, and the unhappy hero of "Under Western Eyes"; by the adorable Rita; by Lord Jim; and Heyst of "Victory"; and the noble Captain Anthony of "Chance"—most of all, perhaps, by staunch, unflinching Captain McWhirr, the hero after Conrad's own heart.

What a world of men and women to have created! In a little biography of him that I wrote several years ago, I spoke of Conrad's "gusto". Someone in a paper the other day reproached me for that, saying that"gusto" was the one word that does not describe Conrad's art—but gusto of creaation I maintain is exactly what he has. .

His own spirit may stay behind, his creations, calm and unmoved, but it is with the gesture of a whirlwind that he sweeps them onto the stage; it is with the mutter of the storm about them that they disappear. Think of the thunderclap of a gesture with which "Under Western Eyes closes; or consider the great scene that closes the lives of Heyst and his lover in "Victory", or that frantic rattle at the door that flings Rita and her young soldier together in "The Arrow of Gold". Is there anything but a very fever of creation.that could work such miracles of impatience and rebellion—and loving acquiescence? And what is the storm in "The Nigger" but the divinest gusto?. . .

Without the Ghosts

AND then, when the ghosts retreat, one is back in the old Kentish house again, watching Conrad's perfect courtesy or seeing him throw his head back and shout with laughter at some jest, or watching him stump round his garden with his stick (gout is his one enemy) mildly trying to attract wild kittens from their lair on the roof, or feeling the peaches to see if they are ripening on the wall.

He hates exercise. He will order the car if it is only a mile that he has to go, and I think this comes again from his reaction against his early life. Not that he bears those early days a grudge. Far from it. He loves to talk of them and tell them over, and count their histories. But one square of English garden and a patch of English sky is enough for him now—if he has the people whom he loves near to him.

Still the mystery remains.

Here, surely, if ever, is genius—the possession by a divine spirit of man's earthly clay. It often seems that he is as little responsible for the creation of those great works as any of us. He speaks sometimes of them—and especially of "The Nigger," and "Nostromo," his own favorites —with exactly the tenderness that he uses for his friends. It is as though McWhirr, and Almayer, and Rita, had stayed for a week or two in the Kentish house as his guests. No more responsible than that. .. Nevertheless it is he that has found them for us, and it is to him that we must pay our debt—not only we, but all the generations that will follow us.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now