Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMy Experience as a Political Speaker

A Personal Contribution to the Presidential Campaign

STEPHEN LEACOCK

THE present year is one in which there, is likely to be a great demand for. political speeches. The only way to deal with this demand is to meet it at the source and to dam it. And I think we all agree that it ought to be dammed.

It has occurred to me that my own experience as a political speaker might be of some use in this connection. In my own country—I live in Canada—the government gets into trouble about onqe every five years, the parliament is dissolved into fragments, the whole country is thrown into turmoil and the government sends for me. The Prime Minister, who leans on me on these occasions, says to me: "Go and speak to them. Quiet them. It doesn't matter what you say; we can repudiate it all afterwards: but speak to them." "And what," I ask, "do we stand for?" "Truth, justice, morality, Christianity, and public honesty."

"Do we stand for these things unflinchingly and fearlessly?"

"We do."

"Do we defy contradiction?"

"We do."

"Do we harbour any animosity, or bitterness, against anybody ? Do we malign anybody, even the dirty pups who are opposing us?" "We do not."

"Very well then," I say, "I am ready. Give me my statistics, my railroad passes, and my expense money—and lend me your valise."

So I set out.

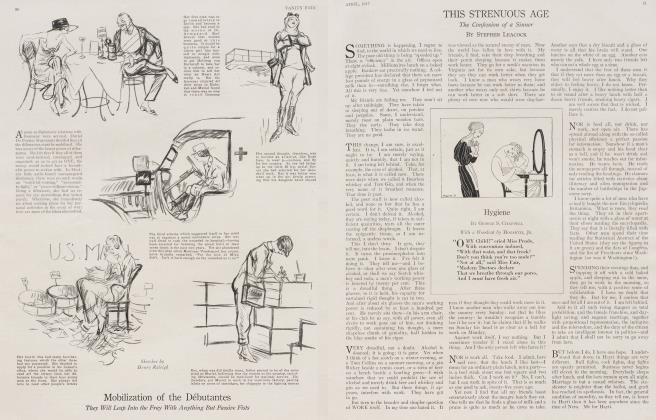

A Technique for the Rural Districts

I AM most usually sent to speak in the rural constituencies. I have acquired quite a reputation as an expert in appealing to the farmers. But it's really a very simple thing. The whole point lies in knowing how to talk to them.

The kind of meeting that I attend—and I suppose it is the same in the rural parts of the United States—is always held at a place called Somebody's Corners. It is in a hall over a driving shed, opposite to a blacksmith's shop. You know when you get there because you can see the farmers sitting on the fence in the dark, waiting. They don't mind how long they wait. For an ordinary meeting it's best to have them wait about an hour and a half. For a big rally, we keep them there till ten o'clock. The hall is lit with two coal oil lanterns, and it has in it anywhere from forty to forty-four people. This fact supplies the opening words of the speech: "Gentlemen, I am glad to see such a big turn-out here tonight." That word "turn-out" is used because a farmer is never supposed to leave home after dark unless he is turned out.

After one has said this then the thing is to begin with a funny story. No introduction is needed. All the farmers understand that it is coming. You simply start out: "Gentlemen, there was once a Methodist minister—" and so on.

After that the real speech begins. Personally, I find that what farmers like best is statistics, facts, documents—something that they can carry away with them. I always say, "Now gentlemen, I'm going to give you something tonight to carry home with you." That gets them.every time.

In one of the last elections in which I operated—it was in 1911—the chief point of discussion was reciprocity with the United States and the chief "document" was a letter from Mr. Taft. I had cut it out of a newspaper and carried it round. Good Mr. Taft had been so misguided as to say that Reciprocity would make Canada an "adjunct" of the United States. That was enough for us. Ours is a poor country, but we are proud.

So at the critical moment of my speech I always used to hold out that newspaper letter —the way to do is to reach it away up into the air, like reaching a handful of hay to a horse —and say: "I wonder if you know what I have here. It is a letter! A letter from President Taft! I wish you could all see this! A letter in which he says we're to be an adjunct of the United States!"

Indignation all over the hall! Cries of "Shame!", "Never!". I don't suppose they knew what an "adjunct" was, but it's evidently not the thing that anybody would want to be.

I soon found, however, that it wasn't really necessary to have the very letter there. Any old bit of paper did well enough. One had only to reach it out in the air and say: "I wonder if you know what I have here? It's a letter, a letter from President Taft!"

In fact, I lost the real letter very soon and after that I found the most convenient thing was to carry out to the meeting the menu card from the hotel where I had had supper. They couldn't tell the difference. I merely reached it out and said: "I wish you could all see this!" They couldn't. If they did they'd have seen "Bacon with one egg, forty cents—with two, sixty" But they never knew.

That sounds very simple. But as a matter of fact it is not every speaker who can do it. In this same election I had with me as a running mate, a Montreal lawyer called Howe, a very brilliant man, but one who was only used to city constituencies. I remember that the first time Edwin Howe spoke to farmers he began by telling them that the time had come for the bourgeoisie to get close to the proletariat. They thought it pretty indecent language for a public meeting.

So after that, as I saw that what he had prepared was no good, I divided up my material with him: one night I had Taft's letter and gave him the figures of trade with Argentina, etc., and the next night I took Argentina and he had Taft's letter and so on. But one night about two weeks later he came to me at the hotel before the meeting with his face absolutely pale with anxiety. I said, "What's the matter, Edwin?" He said, "Taft's letter —I've lost Taft's letter. Can you lend me your's for tonight?"

"My dear Edwin," I said, "you don't need to have the actual letter. Just hold out anything and say: 'I wonder if you know what I have here?' Look, take this menu card, fold it so, and hold it up and say: 'I wish that every man in this hall could see this!' "

What happened merely shows that some men are born for politics and some are not. Some men are conscientious and others are not troubled with it. When Howe spoke that night I could see him getting more and more miserable as he came nearer to the part of the speech where the letter came in. Then at last he reached out the menu card and said in a trembling voice: "Do you know what—" and he paused—"Can you guess what"—and he swallowed—"Do you know what"—Then he gave up, and in a truthful, earnest tone he said: "Do you know what we had over at the hotel?"

How to Make Statistics

BUT second only to documents are statistics. Farmers like them, and they like the best. There is no use in quoting the ones supplied by the government. They lack point. The way is to sit down quietly and make them for one's self. It takes more trouble, of course, but when the whole fate of the country is at stake it's worth it.

The statistics when made should be wrapped in bundles with a certain amount of blue paper interspersed in the leaves. Very good blue paper can generally be obtained in any country store by buying children's scribblers and tearing the covers off. The statistics should be done up with elastics which are peeled off, right in front of the meeting, so as to show that there is no deception.

And of all statistics the very best, the ones that impress and even terrify the farmers are those that deal with the balance of trade. I have never been quite sure what the balance of trade is. But I know that it has an instantaneous effect upon farmers. They're afraid of it. They don't trust it. If you prove to them that it is steadily moving nearer and nearer to them, they get into something like delirium.

This is the way it is done.

"Now, gentlemen, I'm going to show you the balance of trade between this country and Argentina. I wonder if there is any man in this hall who knows where our trade stands with that republic? Is there any man here who does?"

Here it is necessary to pause. If the man is there, one would have to give up Argentina at once. But he won't be. I find that the number of farmers who have been to Argentina is very limited. Anyway, one can always change and say: "I beg your pardon, I meant Paraguay."

But if no one speaks, I always go on thus: "Well, gentlemen, our balance with that country five years ago was eight point six; last year it fell to decimal two. I leave it to yourselves to interpret the kind of danger that that means."

But it is generally wise, after taking up the broad national aspect of things, to come down a little to particulars of statistics near home. For this I generally use either the price of hogs on the hoof per pound, or of marsh hay per ton. Either of these is good. It's just a matter of taste. It's done like this:

"And now, gentlemen, I'll just try to show you how this issue is affecting us right here in our own township. I have here a list of the prices of marsh hay every year for fifty years (sensation). I'm going to read it to you {joy). And when I have finished it I'm going to present to you the figures for the market price right here in the township, of hogs on the hoof for the last seventy years".

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 51

On this, all the farmers settle back for an evening of real enjoyment. By the time all the figures are finished they are practically hypnotized. Any resolution can be carried without dissent.

The Political Importance of Death

MEETINGS held in the country towns are very different. They are generally held in the Opera House or Town Hall and have more size and style to them. There are anywhere from two hundred to two hundred and ten people present. But the town people want sentiment, not statistics—sentiment, something right to the heart. I always used to say to Howe when we spoke in towns: "Edwin, take Taft's letter, I don't need it. Take Argentina and Paraguay, too, I don't want them. I'm going to appeal straight to their hearts."

And of all the ways of doing this, the very best is to remind the audience of the simple fact that some day they are going to be dead. That has the same effect on town people as the price of marsh hay on farmers. I always start out and bury the whole audience, beginning with myself. It is done after this fashion:

"Ladies and gentlemen, the time is coming when the voice that speaks to you tonight from this platform will be hushed in an eternal silence, and when this frame that stands before you" (I always call myself a frame: it is quiet and unassuming) "will lie beneath the green sod of the church yard."

Up to this point, I admit, there is

no emotion. I have even seen something like relief. But wait; that is only the beginning. Next I bury Howe.

"The time is coming, too, when Mr. Howe's voice will be hushed in the same eternal silence."

Here there are visible signs of sympathy, and already a certain apprehension. Then the chairman comes next.

"The time is also coming when this gifted gentleman who has introduced Mr. Howe and myself with such eloquence, he, too, will lie stretched under the grass."

There is evident alarm all over the house now.

"And the time is coming when all this magnificent audience that I see before me, when it, too, will lie hushed in the same eternal slumber as Mr. Howe and the chairman and myself, and buried, like us, beneath the sod!"

After that, of course, the audience are at a pitch of emotion that amounts virtually to hysteria. Then is the moment to turn the topic, quickly and suddenly, with something almost like passion and to say—

"And under these circumstances, standing as we do on the edge of the grave, are we going to let the Americans remove the tariff upon wool ! Never I Never I"

And in the storm of applause that follows, the chairman rises and in a voice that thrills with feeling, says:

"Gentlemen, will some one kindly rise and lead us in singing God Save the Kingf"

These are the methods by which we save our country once in every five years in Canada. They may be helpful in saving the United States. After all, you don't want to be an "adjunct" any more than we do.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now