Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

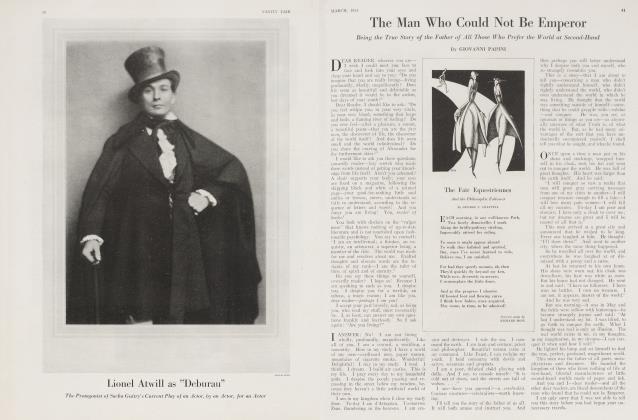

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Prophetic Portrait

Proving that it is a Good Sitter who can Recognize his Own Soul

GIOVANNI PAPINI

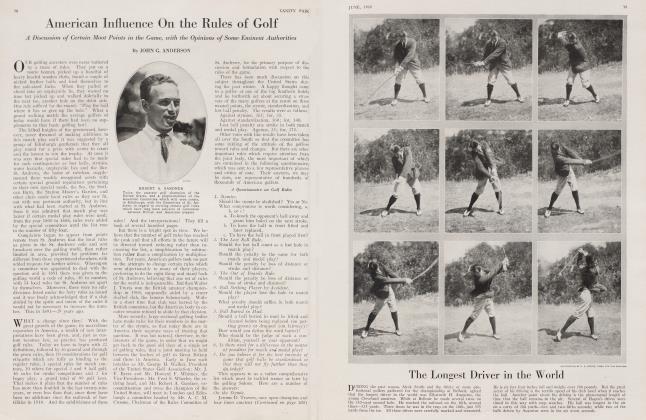

HAVING my portrait painted used to be a passion with me. Most of my friends are artists, and for fifteen years or more I posed for them—seated, standmg, with and without a hat, profile, full face and threequarters. I claimed no reward save that the portraits should be given to me.

My house became a picture-gallery. Every room was full of portraits of myself. Myself, at eighteen. At twenty. At thirty. Myself, proud, contemptuous, lofty, melancholy, gay, fiery, spiritual, abased. Myself, always myself, alike, yet never the same! I confess that when I was left alone with my manifold image, I was often disturbed. It was as if I had given a bit of my soul to each of those innumerable doubles; as if I, myself, were left with an impoverished spirit, stupefied, weary and weakened. I used to stare at myself, fascinated by the diversity of my attitudes. There I was, a youth, full of fire and passion. There, a poet, standing upon a hill-top, gazing off at the hills and the distant sea. Here again, a satanic creature with mad eyes and the onesided grin of a demon. There, a gentleman with blond whiskers. There, a pallid youth with a Byronic forelock. Here, an emaciated mask without neck or shoulders. And always I was I, with and without whiskers, ferocious or gentle, cynic or dreamer. From every wall I stared back at myself with reproach, with mad humour, with a sort of embarrassment.

There is a curious story about this hobby of mine. Six or seven years ago I chanced to meet a young painter, a Russian, who invited me to his studio. His work was abominable—feeble portraits, muddy copies of the old masters, gaudy sunsets and melodramatic cypresses. I didn't relish being painted by a chocolate-box genius and made my exit as quickly as I could. A year later, happening to encounter him again, he surprised me by saying: "I must paint you. Not you, but your soul! I see it. I understand it." He drew me aside and whispered: "I will be frank with you. Things have gone badly in Russia, and I'm awfully hard up. I must make a success of your portrait, or starve."

I HADN'T much faith in the fellow, but I agreed to pose for him. He had moved into a new studio—a bare garret of a place in the poorest quarter of the city. But the old canvases were not there, and Hartling himself had changed. He was no longer a painter of diromos. He had discovered post-impressionism. I stood before his work, amazed and incredulous. He painted with vigorous unconventionality, impatient of restriction, disdainful of form—strange, colourful landscapes, suggestive and horrible; grotesque figures, viscous fruits and exotic flowers.

Hartling watched narrowly the effect of this transformation.

"You are surprised," he said. "I have had a vision—sit here, please. Let's get to work."

He lighted a cigarette and squinting at his canvas, began to paint with a sort of fury. He looked at me, smiling ironically,, backing away from the easel with his head cocked on one side, then leaped forward again, as if he had wrenched some secret from my very soul, and with reckless strokes attacked the canvas like a maniac. He was a tall, thin fellow, with a short beard and pale-blue eyes—usually the mildest and most commonplace of beings. I confess that I was startled by his restless pacing, his ironic laughs, his frantic energy.

After an hour and a half he covered the portrait and dismissed me. I returned for five mornings thereafter. On the sixth morning he said: "I am going to paint your eyes. Look at me as if you saw before you an enemy, an implacable, unconquerable enemy."

In a quarter of an hour Hartling said:

"It is finished. Come and see."

I ran to the easel to see my portrait.

In the center of the canvas, by standing well away, a face that was certainly not my own, could be distinguished. Above a greenish forehead there were two scarlet twists of hair, like bizarre horns. ... A black spot that was an eye. Violet flesh. A pointed nose. Two scarlet daubs where the mouth should have been. And a row of brilliant, enormous teeth, white as tombstones. Beneath the chin, a dirty white collar and shirtfront. About the head, wavering fumes of unearthly colour, like the reflection of some hellish fire. . . .

"What do you think of it?" Hartling demanded. "Original, eh? Not a portrait of you, of course. A portrait of your malign spirit, caught and rendered eternal."

I stared stupidly, sparring for time, acutely embarrassed. The thing was an abominable caricature, an insult. It did not resemble me in the least. Neither was it beautiful as colour or design. Its strangeness was revolting. It was imbecile, ridiculous, absurd.

I told Hartling so. He tried, with a certain indulgence, to explain the meaning of the thing. Dissonance. A portrait of my turbulent self. A caricature of the soul. . . .

I shook my head and went away, determined to see no more of him. Nor did I care to own the portrait. A few weeks later, however, in spite of myself, I returned to his studio. I found the room full of people. Two German buyers were discussing my portrait with enthusiasm. A group of students gesticulated and applauded. I stared at the atrocious thing.

"You don't like it," Hartling said. "I'm sorry, because it's my masterpiece! I'll never paint anything better. I don't expect you to buy it, of course, but the day will come when you'll be sorry that you didn't."

THREE months later I learned that Hartling had sent the portrait to the Salon. My name was printed in the catalogue and I was the object of some very humiliating publicity. "If this is the portrait of Mr. P—'s soul, we shudder to think—" and more in the same strain. I was furious, outraged, horribly offended. There was nothing to do but buy the thing. Hartling asked five hundred francs —little enough—but I couldn't afford it at the moment. I sold my watch, borrowed a hundred francs, pawned a few of my most precious possessions, rushed to Paris and bought it.

When it arrived, I did not even remove the wrappings, but stored my purchase in the cellar and thought no more about it. Hartling returned to Russia.

Five years later, being obliged to move, I came across the unopened package containing the portrait. And, actuated by an uncontrollable curiosity, I unpacked the thing, placed it against the wall, and stared at it.

During those five years I had suffered, loved, hated and desired: I had conquered and had been conquered. Imagine my surprise when I saw that Hartling's portrait now resembled me exactly! In the shadows of the room, the face detached itself from the canvas and floated before me like a reflection of my own tormented mask. The eyes were mine—disillusioned and mocking. The mouth smiled at me, with the identical twist of the lips I had come to recognize as my own—a smile full of malice and pain. So did my own hair twist upward from my pallid forehead like two satanic horns. Me! Myself! My very spirit. My soul. . . . I had looked upon the portrait as a caricature —now I saw that Hartling had painted me, not as I was but as I was destined to be.

Hartling was a genius and I was a fool. I did not rest until I had discovered his whereabouts. He was in Paris, living on the Boulevard des Italiens.

I found Hartling established in a beautiful studio. He was a little older, a little fatter, perhaps, but the same mild and innocuous fellow. He did not seem particularly glad to see me, and when I had stammered out my apology, he said coldly:

"Oh, that portrait! I remember, of course. An abominable thing. A youthful indiscretion. I couldn't paint. I was a fool. Art, my friend, is a scrupulous rendition of the truth. Elegance. Taste. I am a successful painter. I get twenty thousand francs for everything I do. My clients are rich, fashionable. I am an excellent draughtsman. I paint what I see, and I look through rose-coloured glasses. Elegance, my dear fellow! Delicate flesh tints; pearls; chiffon; satin." He placed his fingers together, while I stared with horror at his abominable pink and blue portraits.

I rushed out, speechless with disgust.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now