Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAmerica's Small Town Taste

Some Comments on the Yokel and a Lucid Explanation of the Latitude of the Platitude

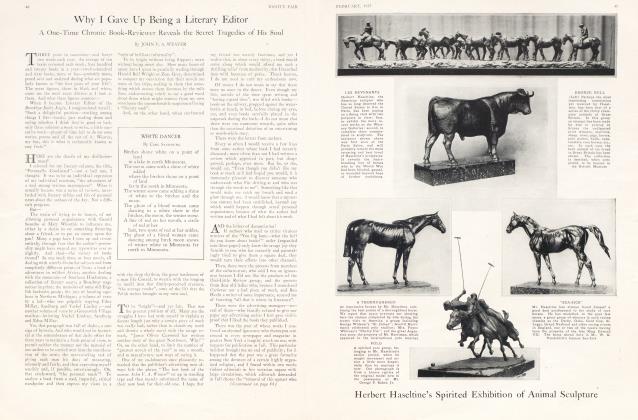

JOHN V. A. WEAVER

FOR the average person, life is one long platitude, in thought, in emotion and in expression; a continuous bromide in experience and in art. Of course, now that "Dulcy" is in town, one expects to hear loud and continual discussion of bromides, their uses and abuses. The night I went to see that excellent satire (I must say, parenthetically) only about ten per centum of the Dulcyisms, or platitudes, made any dent upon the consciousness of the smart metropolitan audience, and loud laughter at fully half the lines was confined to myself, four ushers, and the two authors of the piece, who stood near me, listening attentively after they had finished counting the house, and digging me in the ribs at the right moments.

The ten per centum of platitudes which did get the applause of the house tvere these lines which were preceded or followed by the excellently idiotic laugh which was part of Miss Fontanne's characterization. The audience knew that she had said something silly, because her voice sounded silly, and therefore she couldn't really be in earnest. I am referring, please remember, to the cliches which are the characteristic utterances of the titlepart. The audience laughed reflexively enough at the sections of the play which were unmistakably labelled "satire", such as the activities of those marvellously-well-drawn pests, the "Scenarist", and the "Advertising engineer" who proclaims, "Yes, I think I may say that I have made the nation Forbes-conscious". But most of Dulcy's canned philosophy was accepted as straight stuff; and when things looked blackest for the little woman and her husband, in spite of everything, she bravely announced, "I always say that the darkest hour comes just before the dawn", many were the hands which beat together sympathetically, while not even a smile spoiled the onlookers' perfect understanding and approval of her fortitude.

The Nuisance of the Normal

"DULCY" will, I am convinced, have a great success. But that success will be for reasons other than the wonderfully consistent conception of the title-role. The denizens of the theatres recognize humour all right when it is accompanied by a kick in the Hartschaffners; they grin from ear to ear when the comedian says, "I get a fellow-feeling for Carpenteer; boy, ain't I been married three times?" But when Dulcy urges, "Everybody come to breakfast, now, before the grape-fruit gets cold, tee-hee", the fat lady with the large box of candy remembers that she made just that remark only last week, and it was very cute, as she recalls it, and it does not seem in the least obvious or ridiculous; so she smiles pleasantly, and sees no cause for derisory guffaws.

No, most of the hundred million of us are platitude-bound. We want nothing very subtle or very new. Especially we want nothing very good—that is, "good" as the critics, those stuck-up creatures, see it. "Back to normalcy" is something more than our leader's slogan; it expresses the heartfelt inward wish of the average person, who comprises the greater part of the population.

The normal—"The Golden Mean" of the Greek philosopher and the Roman poet—is there not a definite pun in that classic phrase? For what could be meaner, more annoying, more wearying, than the "average" thing? It is bad enough to listen to an average man's conversation. But for anyone with any sensibilities to have to accept what the average person accepts—yea, demands—for his amusement or artistic delectation—well—

I always feel greatly annoyed when the amazing truth of a platitudinous observation is brought home to me. But that's the deuce of a truism—it's so confoundedly true. When I used to hear some comedian commenting on the sleepiness of Philadelphia, the rubberplants and baby-carriages of Flatbush, and the Southern-colonel type of Southerner, I used to think, "Why, this is just trying to be funny; these things can't be exactly so". But when I saw these phenomena face to face, I realized that the so-called jokes were, in sooth, nothing but platitudes. The comments were exactly, heart-breakingly, so.

The Taste of the Native Yokelry

AS I said before, we in the city know that the metropolitan citizens for the most part consider the movies "good enough", despite the examples of "The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari" and "Passion" in worth-while movie-making; we bow our heads to the fact that the motherin-law joke, the patter of little feet, and the frantic grimaces of the wronged husband are amusement, pathos and drama, respectively, for the general. It may hurt us, but it cannot be denied that paintings like "The Horse Fair" and "Cherry-ripe" will always be art for the average man, while a painter of even so elementary an appeal as Gauguin is always looked at a bit askance, that in sculpture Rodin is viewed mostly with a bewildered respect, while hearty admiration goes out to "The Good Fairy". But the rube, or the inhabitant of the small town, is he as bad in matters of art and taste as he is painted ? Is he, as we big city fellers are always telling the world, even worse than we are?

He is, kind friends, he is. If the taste of the city is discouraging, the hinterland is appalling.

There is no doubt about it. Main Street is just like the feller says, and no amount of violently-expressed indignation can disprove it. I made a pilgrimage this summer into the middle west and the middle east; I went into the homes of some thirty farmers, picked at random. I stopped in two small towns in Iowa, three in Illinois, one in Indiana, one in Michigan, and three in upstate New York.

You've heard jocular remarks about pine wood-work which farmers have refused to leave in its regular inoffensive, even pleasant, state, but have tortured with yellow and brown paint into a burlesque of oak? And the sea-shells tied with pink ribbons, and the bird-pictures made from real feathers, and the portraits of light-houses where the beams of light are fashioned from mother-of-pearl, and the sea-scenes with real, honest-to-goodness sand pasted on them? They are there, friends, as much a part of the rural scene as the separator into which all the milk is immediately poured each morn and night when the family sits down to canned vegetables and chicory whitened by evaporated cream. There in the book-case you will find the well-thumbed copy of "St. Elmo" or E. P. Roe books. On the table stands the SearsRoebuck catalogue and the various farm journals. If anybody wants anything better for amusement, he can hop into the flivver, or the Studebaker or the Dodge or (in many cases) the Packard, and go to the movies in town. Materially, the farmer gets along very well, for the most part, these days. He doesn't care three whoops for beauty. Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe he gets great aesthetic pleasure out of the play of the sunset upon his trees, the waving in the breeze of his long green com.

Music and Books

DON'T think I mean to maintain that there may not be some tillers of the soil who get their minds away from tractors and spreaders at intervals and place a bit of decent chintz at a window, tear down the chromo of "Good Night, Fido" to make room for an unobjectionable print or even for an etching, and take a nose-dive into a book of real value. What I am talking about is the normal, average hick, who is a hick, world without end, amen.

There may be a forlorn Carol Kennicott or two in each of the bush-league towns I visited. She is the exception. The Victrola and the foot-propelled piano supply the normal music. In the country it is principally the Victrola upon which (besides jazz), sentimental quartettes, "talking pieces," and such jewels as "Overture, Poet and Peasant" are ground out.

But the whole problem lies much deeper than the farmer! In the small town a second-rate red seal record thrusts up its head now and again from the welter of syncopated tunes and "Dance of the Hours", "Overture, Wilhelm Tell" and such, much like a geranium in a weedy window-box. The record-rolls often get as high as Nevin or even MacDowell.

There's no use going into the details of small town taste. It's just as bad as Mr. Lewis and others say it is, and a good deal worse. I saw three iron deers on one lawn, but after all, you can discover these in Lake Forest, Chicago's most fashionable suburb, and even on Riverside Drive, where these creatures share the green sward with Shakesperes and antelopes.

There was just one matter that I took special pains to look into thoroughly; it was a subject very near my own heart, and it allowed of easy investigation. I mean, books.

Just what would you expect the jay-burghers to read? Well, you're depressingly right. I went to the bookstores in each town, and found the results everywhere practically identical. One bookseller, with a weary smile, showed me the score of his ten biggest sellers during the I inquired about the inclusion of "Main Street" in the list.

past year. Here it was:

Harold, Bell Wright's latest. 42

Zane Grey's latest. 48

James Oliver Curwood's latest. 39

Ethel M. Dell's latest. 32

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. 37

Gene Stratten-Porter's latest. 44

Eleanor H. Porter's latest. 36

Joseph C. Lincoln's latest. 31

Robert W. Chambers' latest. 30

Main Street. 29

Continued on page 96

Continued from page 52

"Don't know why they bought it, mostly curiosity, I suppose. But they sure hate it. I can't remember one yet that didn't come in, sore as a boil, and holler about it. They say it's all lies. I ain't read it yet".

Well, sirs, there you are.

The average taste indicated by this list is just what you'll find from the rock-bound coast of Maine to the sunkissed waters of the Pacific, and points east, west, north and south. There are exceptions, naturally, but the exceptions prove the rule to be a rule of the mediocre or of the downright punk.

The utterer of the platitude is the reader of the platitude and the thinker of the platitude. Taste improving? Pish, and three loud tushes. What does it matter, anyway? The average man is just as happy, just as contented, just as smug as if he really knew something about any of the arts, and talked in un-canned phrases.

Art, on the other hand, will worry along, somehow, despite "dumbbells", experimenters, and exploiters.

It always has.

And, you know, "Where ignorance is bliss"—as I like to say.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now