Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRollo in Society

New Adventures of An Old Friend Written Somewhat in the Ancient Manner

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

Prefatory Notice

IT will come as a surprise, doubtless, to readers of the present generation to learn from the title at the head of this page that there is promise of a continuance of the stories relating to the doings of that manful if, sometimes childish, little fellow, Rollo, from whom our parents in their youth derived both instruction and entertainment. This is indeed happily so, and while the discoverer of this new series of adventures cannot claim the credit of original authorship, he is willing to waive that authority in view of what he feels to be the importance of Rollo's message to the modern social world. Surely never more than now are needed the amiable and gentle qualities based on right and virtuous living which ever actuated our little hero in the past and from which many a useful lesson may be learned by young and old to guide them through the perilous paths of the present, to say nothing of the future.

The Move to the City

WHEN Rollo was between ten and eleven years old he was seated one day in the little arbor which Jonas had built for him. He was playing with some bright stones and shells which his Uncle George had brought him from the seashore, setting them in rows on the edge of his comfortable bench or, again, marching them in columns as he had seen the soldiers go during training-week. One shell in particular, Rollo admired greatly. It was a large clam-shell in which was a beautiful picture of a lighthouse and a ship in the distance and below were the words "Souvenir of Atlantic City."

"How pretty," thought Rollo, "and how clever of a clam to decorate his home so! But I did not know that they could also write."

While he was absorbed in these reflections he heard his mother's voice calling "Rol-lo, Rol-lo."

At first, Rollo had a great mind not to go for he disliked being disturbed while he was busy with his shells. However, he finally decided it would be best to obey, so, gathering up his stones and placing the clam-shell in his pocket, he ran toward the house. In the entry he found his father, his mother and Jonas awaiting him. It was evident from their expression that something of importance had happened.

"What do you think, Rollo?" his mother inquired. "We are going to move to the city." ' "HURRAH! HURRAH!" cried Rollo, and then once more, "HURRAH for Atlantic City."

"Atlantic City?" said his father. "What ever put that idea into your head? We are not going to Atlantic City; we are going to New York."

"Oh, bother," said Rollo, crossly, adding, "but if there are lighthouses and ships there I shall not mind."

Now this was very wrong of Rollo, for he should have known that it spoilt the pleasure which his parents had hoped to find in surprising him. Children often behave so by acting natural when they should know better. Rollo's father was considerably vexed, but, realizing that Rollo was still young, he said kindly, "You have many things to learn, my son, but fortunately you still have time in which to learn them, and New York will do very well to begin with. Atlantic City may come later. But come, we must be off to the photographer's studio. Hurry, Rollo, and put on your Sunday suit. Uncle George and James and Lucy will be waiting for us."

While Rollo, a very excited little boy you may be sure, was putting on his blue roundabout and his white collar, his mother explained to him that, since they were going to the City to live for a while, they would be expected at certain times to go out in Society.

"What is Society, Mother?" asked Rollo. Rollo's mother was silent for a while before she replied. "That is a difficult question to answer, Rollo, but I will try to explain. You know that here at home you see a few people very often whom you know very well. You play every day with your cousin Lucy and your cousin James, and Jonas instructs you in piling wood and digging potatoes. But that is not Society. In a great city like New York you will occasionally see a great many people whom you hardly know at all. That is Society."

"And will I not be instructed in digging potatoes?"

"No," said his mother, "I think not."

"Oh goody! goody!" cried Rollo,—"I am sure I shall like it. But why do we go to the photographer's studio?"

"That is my idea," said his mother. "You may not realize it, but we go to the city and will meet a number of strangers."

"I can readily understand that," said Rollo, who was a bright little chap thoroughly interested.

"Therefore," continued his mother, "it is more than likely that when the news of our arrival begins to be spread about through the city there will be an immediate demand for our photographs."

"Yes," said Rollo, rather peevishly, "but I do not see why Uncle George, and Lucy and James have to be in the picture. And Jonas, is he important? O-ho!" Rollo laughed at the very idea.

Rollo," said his mother quietly, "you do wrong to laugh so. Your Uncle George and Lucy and James are going with us to the City. They are to share our new home, for we have rented our farms to two New York gentlemen for a great deal of money, much more than it will cost us to live in New York if we all live together."

"But Jonas is the hired-man," objected Rollo.

"From now," said his mother, "he is not the hired-man. He is your father's secretary."

"His secretary!" cried Rollo. " I do not understand?"

"You do not have to," said his mother. "Come along; the chaise is waiting."

At the Photographer's

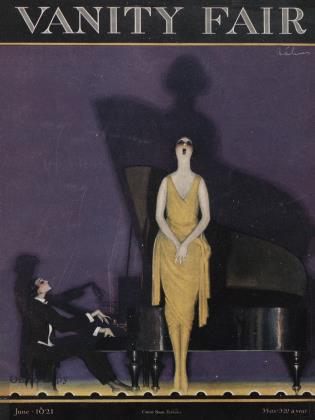

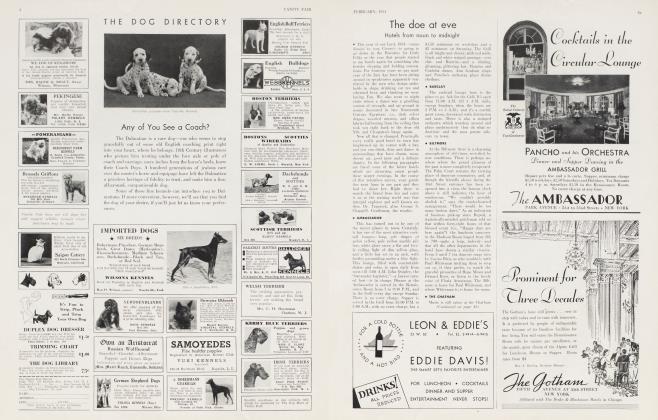

ROLLO was so delighted to hear of something that he did not have to understand that he was quite the happiest of the family-group, a cut of which embellishes this chapter. Indeed it was necessary for the photographer to ask Rollo to please not look so pleasant before the picture could be taken. Mr. Bishop, the photographer, was anxious to take separate pictures of each, even including Jonas, who looked surprisingly well in his other suit, but Rollo's father said kindly but firmly, "No, Mr. Bishop, that would be putting me to unnecessary expense, which would be wrong. You have said your price is three and one-half dollars a dozen. I will purchase a dozen of the pictures if they are satisfactory, and cut one up if the occasion requires. Should an enlargement of the central figure be demanded, I presume it can be arranged."

As the family were driving home from Mr. Bishop's studio, Rollo who sat on the front seat with Jonas said, "Jonas, why did Mr. Bishop tell Lucy and James and me to watch for the little bird in the hole in his camera when there was no little bird?"

Jonas, with the butt of his whip, humanely removed a large horse-fly from the flank of Old Trumpeter before he said, "Mr. Bishop spoke of the little bird merely to attract the attention of you and your cousin James. While it is true that there was no little bird—or at least, I saw none—it is equally true that you and James were exceedingly restive.

"But Jonas," continued Rollo, "if there was no little bird, did not Mr. Bishop tell a lie?"

While Jonas was thoughtfully removing another horse-fly from Old Trumpeter Rollo's father leaned over his son's shoulder and said kindly, "My son, you must not disturb Jonas while he is driving, or we shall soon all be in the ditch. It is only reasonable to suppose that Mr. Bishop was mistaken in thinking that there was a little bird in the studio. Or there may have been one under his black cloth. Did you look under the black cloth?"

"No sir," replied Rollo.

"And did you look in Mr. Bishop's darkroom ?"

"No sir," again replied Rollo.

"Then you see, Rollo," said his father, "you may well have been mistaken. Let us say no more about it."

Rollo's family now felt themselves thoroughly equipped to receive and to mingle with society. How they did so will be described in the next chapter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now