Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAmerican and British Relations at Golf

An English Authority Shows Us that International Sport Makes a Heavy Draught on Tolerant Good Will

BERNARD DARWIN

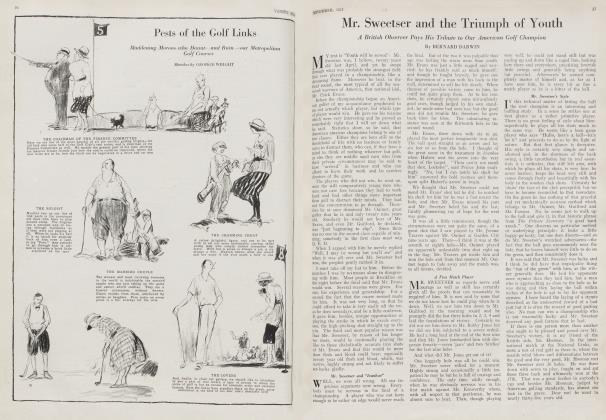

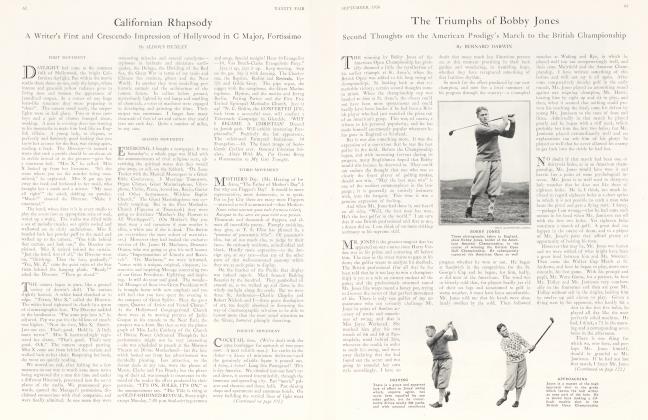

ON the morning when I intended to sit down to write this article, I received a letter from one of my friends of the American Amateur Golf team, which came pat to my purpose. I should like to publish it, but I cannot do that. I can say, however that it was so cordial towards the golfers whom the writer had met here this Spring, so grateful for the little that we had managed to do for him, so sincerely anxious for more and more friendship between the two people, that it was a wonderfully pleasant and encouraging document. It was the more encouraging because on that same morning. I had felt a little dashed by reading the report of an interview with an American professional, just returned from here, who seemed very much dissatisfied with us. That interview has since, I am glad to say, been toned down and reinterpreted to us.

Hagen's Popularity With British Golfers

PERSONALLY, though I have a natural sympathy for those who make their living by writing for newspapers, I could sometimes find it in my heart to wish that all interviewers —on both sides of the water—could be shot on some glorious dawn. I do not believe that people say the things that are attributed to them in interviews, or if they do say them they generally don't mean them for more than a minute, and ought not to be allowed to say them in public.

At any rate, we over here shall continue to wish that Hagen should come and play again in our Championship; we have a genuine admiration for both his golf and his courage. If one or two spectators gave war-whoops when his ball went into the bunker at the last hole, it was no more than a momentary and irresistible outbreak of pent-up excitement. It came from just the same cause that makes people titter and giggle at some particularly tense moment in a theater. It was a purely nervous reaction, and to call it "applause" as if it were set and deliberate, is a misuse of language. The real feeling of the crowd towards last year's Champion was shown by the hearty clapping which greeted him as he left the last green beaten by one stroke, a very brave and rather unlucky loser.

As to the question of the "pinched" clubs, I think that "least said soonest mended". And is there anything really to mend? Our rule on the subject of the faces of clubs, whether it be intrinsically a good rule or a bad one, has been known for some while now, and to talk of the "last moment barring" of the clubs in question seems to me quite inaccurate, and there I propose to leave the question.

It would be, of course, an ideal state of things, which may come to pass yet, that golf should be played under exactly the same rules on both sides of the Atlantic. At present there are some differences in the law. There is the matter of the Schenectady putter, as to which I am often inclined to think we were too pedantic, and there are the ribbed clubs, as to which I think we are right. There was also the stymie, but on that point there is now unanimity. Whichever of us is right or wrong on the other points, does it greatly matter? When we come to you, we play your rules, and when you come to us, you play ours.

I have had the pleasure of playing in matches against American teams in both countries, and it seems to me quite simple, easy, and natural. I believe it always does seem simple to the players. The people who make or imagine difficulties are those who do not play in, or even watch the matches, and only read what somebody has got to say about them—somebody very often, who wants to say something that shall, in journalistic language "create a sensation". These differences in the rules, such as they are, do not in the least affect the spirit in which we are all agreed the game should be played. They make only a very small demand on our powers of give and take.

Contest a Means to Understanding

THE more American and British teams play against one another the better they will come to understand one another. That is a perfectly commonplace remark, but it is worth making, because the recent interchange of golfing visits, has shown it to be so profoundly true. There have been a great many people over here, who, with no first hand knowledge to help them, got it firmly fixed in their heads that American golfers made what they call 'a business of the game' and were dour, gloomy opponents. Some of us who had more experience, tried to din it into their heads that this was not so—that the American golfer, though he practices hard, and is in one way tremendously in earnest over the game, yet plays a match more light-heartedly and smilingly than the Englishman does. Sometimes they believed us, sometimes they raised their eyebrows and remained politely incredulous.

I feel confident that this summer's visit of the American team has at last convinced them that they were wrong. They saw with their own eyes in how cheerful and friendly a spirit that team played. When the team first arrived many people used to say to me, "Are these American golfers good fellows?" A little later the question took another form. It was, "These American golfers are awfully good fellows, aren't they?" That little difference is surely eloquent.

To take the other side of the picture. I do not, of course, know so well what the average American golfer thinks of us. I will make a guess, however, on just one point. He thinks us, I fancy, rather hidebound, antiquated and conservative, and entirely convinced that our point of view on any particular detail of the game must be right, and that anyone else's newer point of view must be wrong.

A Tale of St. Andrews

MR. ROBERT GARDNER told me a nice little story at St. Andrews. In a practice round he did the last hole there in two; he pitched the second shot up on to the plateau green with his mashie-niblick, and the ball duly rolled in. This rare feat of his being mentioned in the Clubhouse, a Scottish golfer said "Ah, but you did not do it in the orthodox way!" The orthodox St. Andrews way, I may explain, would have been to play a running shot on to the plateau. I cannot help fancying that that Scotsman was not wholly serious, and was making a grave joke for Mr. Gardner's benefit. But he may have been serious, and if he was, his remark may have been rather typical of some British golfers. But I hope we are not all quite so fiercely conservative as that, not so unready to admire what may be new in the game.

We have had some such differences of point of view amongst ourselves. When the Golf boom first came to England, the English golfer did not by any means accept everything from St. Andrews as sacred. He had different notions. He invented Bogey for instance, a useful institution with an unfortunate name. He liked patent clubs with no heel, a curly neck, or what-not, and did not care whether they looked like traditional golf clubs as long as they would hit the ball. The Scottish golfer thought him at first perhaps an iconoclastic person, not properly brought up, and the Englishman retorted by thinking the Scot an old stick-in-the-mud. But both have modified their views, each has absorbed something useful from the other, and they play the game very happily together.

(Continued on page 104)

(Continued from page 74)

If I thought there was some one thing about the game which you could learn from us, it would be impertinent for me to indicate it, but I may perhaps allude to one thing that you have learnt and improved upon. Once upon a time American golfers were laboriously slow; they took many practice swings and altogether made the game rather tedious. They discovered their fault, and took to playing the game far more briskly. Meanwhile we, whether in pious imitation of American visitors or from some obscure cause, became more careful, and more slow until now it is we who are, by comparison at any rate, the slow players. By showing us this you have done us good, I think, and I hope that we shall hurry up accordingly. Your players have taught us, too, something in the matter of temperament, though whether one people can imitate another's temperament is doubtful. The American takes more trouble over the game than the Englishman, lie gets lessons, he practices, and yet when the match arrives he plays it gaily, with a joke never far away from his lips. We not work so hard at the game, and yet whpn we come to a match we arc apt to grow somber and solemn. Sandy Head says in his book that when he was young he was reproved by a famous Scottish caddie of the old school with the words, "No Champion was ever freevolous." I wish you could teach us the secret of putting a little efficient frivolity into our Championship golf.

Another point of a different kind, in which I hope we shall learn something from you is that of public golf. There are now a large number of Municipal Courses in Scotland where golf has always been the people's game, but England still lags behind. It is beginning to wake up in the matter now, but we have still a long way to go in order to catch up with—let us say, Chicago or Toledo—indeed I don't suppose in the least we shall ever do that, but we can try to put ourselves right.

Trivial Misunderstandings IT is painfully easy to take games too seriously. It is easy to write solemn nonsense about them, and to exaggerate their importance. Yet in one respect I don't think one can easily exaggerate their importance, namely their very great value in promoting friendliness and good feeling between the nations that play them. The harm that may be done by some trivial misunderstanding, the good that can be done by international matches fought out in the right spirit, it is hard to measure. As far as golf is concerned I think nothing but good has been done. My kind correspondent says in his letter: "Of course there was only a handful of us, but we are widely separated, and our bit in the way of propaganda may well have its value". I am sure it will and the more teams of such good sportsmen come over to us, and the more we can do in returning such visits, the better for both of us, and all of us. Winning the Walker Cup is a great thing, and we only wish we could have done it, but the playing for it is much greater.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now