Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

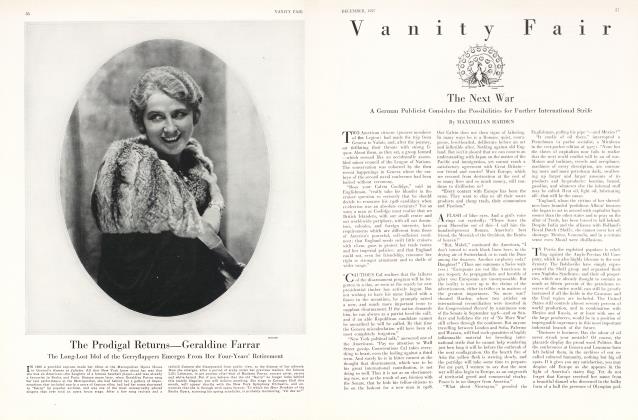

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Problem of Reparations

A Famous German Political Philosopher Proposes, As a Conclusive Solution, the United States of Europe

MAXIMILIAN HARDEN

CAN the Reparations issue be settled? It will not be settled by executing, or trying to execute, the Treaty of Versailles. It will not be settled by continued diplomatic negotiations between France and Germany. It will be settled in the end only by getting down to the fundamental causes of Europe's trouble, of which the Reparations dispute is but one symptom; not by the U. S. A., but by the U. S. E.—by a new federation of the United States of Europe.

The busy American, who is tired of propaganda and out of patience with an imbroglio which seems too intricate to be grasped, can best find his way through the European muddle by keeping these three basic points in mind.

The Treaty of Versailles will not be carried out, because it cannot be carried out. It is not simply that the Treaty is harsh towards Germany. The essential fact is that the Treaty is incompatible with the known laws and the known demands of modern economic life in Europe.

The basic error made in framing the Treaty four years ago lay in assuming that Germany, with a little honest effort, and leading for a time a life of humility and industrious poverty, could, all by herself, make good the damage the World War caused to five great powers and a great number of little ones.

This assumption—which may have seemed plausible enough to men still burning with the hatreds of war—can easily be refuted.

The Impossibility of Payment

IT was soon recognized by everyone that the Treaty could not be applied to the letter: for one thing, the Allies abandoned their plan to extradite and punish various individuals in the German army and government; in the second place, a German liability originally placed at 132 billions in gold marks now fluctuates in the minds of the Allied diplomats between forty and fifty billions.

How, indeed, could Germany, quite aside from the cold fact that her currency has shrunken to one millionth of its normal pre-war value, ever pay the 132 billions in gold which the Treaty contemplated and without which there can be no reparations in the sense of the Treaty? Is she to pay in cash, or is she to pay in goods? And how may the payments be adjusted to avoid ruin?

She can pay in cash only by discontinuing all imports and at the same time increasing to a maximum the export of cheap merchandise—that is to say, by "dumping" her goods on the world markets.

Now as for "dumping", such a procedure on the part of Germany would soon become intolerable to other exporting countries, no matter how strong these might be: it would inevitably produce panics and unemployment. America has already protected herself by a rigid tariff against any influx, en masse, of foreign articles; and not even the British Empire, with its long tradition of free-trade, could long keep from doing the same thing. Quite lately, Mr. Joseph Chamberlain has put forward a program whereby the English should follow in the footsteps of the United States, reserving the English market exclusively for English wares, and so changing the crisis of unemployment to a crisis of labor-shortage and bringing about a condition of great prosperity in the country.

It is true that France does not see the situation in this light. The economic interests of France are totally different from those of the countries which have been allied or associated with her since 1914. France is the only great power quite able to support an unlimited flow of German exports with equanimity. The French population is relatively small, and lives on a fertile soil: it is a population of small farmers, small tradesmen, small investors. The world's foremost dealer in articles of high finish—objets de luxe"—France has never entered the scramble for the world marketing of cheap wares. Her industries, to survive on a prosperous basis, do not have to underbid competitors in the export field.

But this independence, which is, in itself, a tremendous advantage, harbors a very great danger for France—the danger that she will find herself isolated in the political world, whenever she follows a policy rigidly based on economic interests. In the present case, France could force "dumping" upon Germany only at the expense of alienating her allies.

An analogous reasoning applies to the curtailment of German imports. Whether France could endure the closing of German doors to her wines, liqueurs, art objects, silks, laces, dresses, hats, soaps, perfumes, jewelry. cosmetics, vegetables and fruits is a question I think hardly worth discussing. This recourse (cash payments from a surplus in trade) will never be resorted to so long as the United States, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, Japan and the new Slavic states, have anything to say in the matter.

The Manner of Actual Payment

BUT perhaps Germany might pay, not in cash, but in goods, passing over to France and Belgium the value, say, of fifty (or even thirty) billion gold marks in tools, farm implements, manufacturing machinery, furniture, building materials and the like. But this would mean paralysis, for years, perhaps for decades, of French and Belgian enterprise in these departments of production. Not only this. Once German machinery has been imported, all parts and replacements—all the essentials for repairs and maintenance—would have to come from the German firms making the original installations. Experts with greater technical knowledge than 1 might be able to estimate the length of time it would take the French to recover from the effects of an indemnity thus collected.

These facts, it. will be observed, would remain unchanged even were the United States to make the much talked of, the much hoped for, loan of seven billion dollars toward the liquidation of the indemnity obligation. That American statesmen are intending any such thing I gravely doubt. You Americans hold three-fourths of all the coined and coinable gold in the world; and your country has such possibilities of development that there is no danger that Uncle Sam may starve, like King Midas, amid his bags of treasure. So insistent is the impulse toward industrial expansion in the United States that American manufacturers are for ever clamoring to have the doors of immigration opened wider. Though America is the only country still rich enough to afford the luxury of political idealism, she cannot help noticing that there are numberless opportunities for safe and profitable investments of capital in Asia, in Russia, in Australia and in the Balkans, in all lands where lack of coal (Holland and Italy, for instance) will shortly compel general electrification. In these conditions, what attractions can a loan to Germany have a loan yielding but low and dubious interest, and repayment of which in any visible future is out of the question? The minimum premise for such a loan would be the absolute pacification of Europe, and a period of earnest co-operation among all European states, of which I shall speak more fully hereafter. Otherwise, the New World would be trickling drops of water into the bottomless pit of the Old. And would this assistance really help Germany to her feet? She cannot manage her finances at present. Suppose we add to her other burdens the interest and amortization of five billion dollars— twenty quadrillion billion paper marks!

Put it in this way: whatever Germany pays her neighbor as debtor, she must refuse him as customer. Every billion spent on reparations is lost to the trade of those who would sell. Experience, which is a hard teacher, has taught us that the dislocations in industry caused by such losses are harder to bear than taxation and empty treasuries. Borrowed money never, by itself, increases the fortune either of an individual or of a nation. Work, and work alone—under "work" I must here include prudent speculation and the well-advised spending of the wealth that work creates— can bring a real and a durable reconstruction.

The Vicious Circle

SUCH is the stone wall against which the Treaty is breaking itself to pieces. We cannot alter economic laws to our will; we must adjust ourselves to them. This simple truth never came home to the "Big Four" in Paris. Only one of the "Big Four" was really "big" in the nobility of his ideals and intentions. I refer to President Wilson. But even he shared with his t hree colleagues a general obtuseness to the principles of world economics, and a profound ignorance as to the things that were economically useful, essential, possible, for the nations of Europe.

The result was a Treaty which has lamentably fallen because of its own weight.

Meantime—and this is what the foreign observer is not likely to understand—Germany has been forgetting Bismarck.

Let us grant that the Treaty is not workable. Is Germany thereby excused from doing her best to meet her reparations obligations?

By no means!

The unbearable is never borne; the unfulfillable is never fulfilled. Then why so much agitation? Bismarck, the one great statesman our country produced, used to insist, over and over again, that love and hatred, sympathy and antipathy, moral indignation, holy horror and vindictiveness, are not political concepts and should never influence statesmanship. Why, then, this howl of rage in Germany against the "infamy of Versailles", which the loser of a monstrous five-year war could not hope to have much milder and the absurdity of which must soon assert itself?

Why? The answer is easy. It is German politics—domestic German politics.

Thinking people the world over must be impressed by the distortions of which the patriotic emotion is capable, and the misuses to which it may be put. It is being vigorously used in Germany today, and used in exaggerated forms. A military monarchy has been overthrown. A dozen princely courts have disappeared. Thousands of individuals have been deprived of influence, of position, of privileges, of sinecures, of easy sinecures for themselves, of promising and secure futures for their children. Naturally, these people are hoping for a restoration and they are trying to bring it about through nationalism. Now, nationalism best flourishes in an atmosphere of hatred for others, in the one direction, and of glorification of self, in the other. Its doctrines are best stated in terms of accusation, goading the national pride by disparagement of other people, by calumny of individuals and parties holding different views; by unceasing repetition of charges that the dignity of the race is being daily and grossly insulted by some jealous neighboring race.

Pan-Germanic Nationalists

FROM year to year, since the Armistice, the power of the German Nationalists has been gaining ground in this young Republic which has been the victim of unbelievably incompetent administrations. I must add, parenthetically, that the Nationalist ranks count not a few sincere believers in the virtues of the Old regime, and in the irremediable rottenness of the New. Hundreds of unpunished assassinations; innumerable cases of violence to persons and property; daily, almost hourly, examples of lawlessness of every kind and description, have made the Nationalists so feared and so powerful that courageous indeed must be the man who would oppose them openly, or publicly champion the cause of truth and common sense. Not all classes of society, to be sure, are equally responsive to Nationalist pressure: labor, for example, and the small business men are more or less free; but these classes are being continually betrayed by their leaders, whom the Nationalists often corrupt. They are not in a position to control the trend of public discussion. "We are being lied to even more than during the war!" is a remark constantly heard in the streets of German cities; but the lament is followed with a sigh of resignation: "What, alas, can be done about it?"

The trick the Nationalists have turned in Germany is an unparalleled example of crafty and successful demagogy. Here we are, less than five years removed from the most appalling defeat a nation ever suffered in all history. And yet—after a political volte-face, engineered by the intrigues of a few and accepted by the apathy of the many, and which is spoken of as a "revolution" though it never was one— whom do we find in popular favor? Who are acclaimed as the saviors of their country? The very men, if you please, who led Germany into the war, and who then lost it for her; and who either escaped the consequences by cowardly flight, or proved by dozens and dozens of prophecies and diagnoses which never came true, that they were utterly lacking in political intuition and reliable political judgment.

The Fickleness of Popularity

ON the other hand, ostracism and death for those who saw the mistakes that were being made and gave warning against them; ostracism and death for those who refuse to accept the Nationalistic creed. And what is that creed? It holds that of all European governments, only the Imperial German government was spotlessly innocent of bringing on the war; that Germany was not brought to her knees by force of arms and weight of superior numbers; but by the revolutionary dagger-thrust sunk from behind into the Army's back; that Germany was betrayed into accepting the Armistice by the same Benedict Arnolds who later delivered Germania's bleeding body of the monstrosity called the "Republic"; that, finally, the Treaty of Versailles, word for word and paragraph by paragraph, is a thing of deceit, a crime of crimes.

With such a propaganda rampant over the country, was it possible to create a public will to meet the demands of the Treaty? -in deed I mean, and not in words? How could that unfortunate known as "the man in the street" help feeling that it was just to yield as little as possible to the tyrant Allies who started the war, owed their victory to spies and traitors, and now desire nothing beyond the dismemberment of Germany and the enslavement of the German race? But, meanwhile, the effects of this state of mind on public policy have been disastrous; and our mistakes may be enumerated one by one.

The first mistake was at Versailles. The sane and wise policy of the German delegates would have been to smooth off the sharper corners of the Treaty—replacing the ruinously costly and pernicious occupation of the Rhinelands by some equally secure but less galling guaranty; and contesting those provisions which, in violation of the spirit of the Armistice, loaded soldiers' and widows' pensions upon Germany's shoulders (a burden she cannot possibly assume). For the rest, if the Treaty were inherently unreasonable and absurd, its weaknesses could not fail to make themselves evident in the course of a very short time. Whereas the actual procedure was to raise a shrill and ineffectual outcry against the "Treaty of Shame" en bloc, and that in an antagonistic spirit which made the victors at once conclude that any abrogation on their part of details would only strengthen German resistence to the whole document. Nevertheless, the Treaty has been revised on some minor points, as I have explained.

Errors in German Policy

NOW, though we Germans have no right to demand a revision of the Treaty, I believe that such revision will be imposed upon the Allies by their own necessities; and evolution in this direction would have been much more rapid had it not been retarded by a common suspicion that out of this Germany, which is new in external appearances, the old monarchical and militaristic Germany, the Germany of subsidies and rebates that made her the under-bidder of all competitors on the world's markets, might suddenly be born again. This suspicion, this fear, has been engendered by a number of unfortunate blunders, of which I shall here particularize the greatest.

After her defeat, Germany made improvements in her rural and municipal economics which would have been scarcely possible in normal times. This situation was the result of the colossal profits accumulated by individuals and firms during the war and the blockade; and it was helped on by the depreciation of currency and the "dumping" of securities upon the country, which, down through the year 1922, greatly favored the export trade. The German peasantry, in fact, is now virtually out of debt. Why not, if twenty-five cents will pay off a mortgage of a million marks? Even in the most backward villages new buildings with all the modern improvements have been going up. Large and small land-owners sit enthroned on mountains of paper money (why not, again?). An ox brings five hundred million marks in the market place; and a clean-up of dead wood in a small forest nets a hundred millions! The technical equipment of German factories has meantime been attaining a perfection which cannot possibly be surpassed today or tomorrow.

Now, for a time, the United States, England, Italy, Holland and Scandinavia suffered from unemployment, and much more severely than Germany did. This surprising anomaly was due, nevertheless, to natural causes; and it was a blessing besides, for only under such circumstances was the payment of reparations by Germany possible. However, the German government did not seize its opportunity. It made the unpardonable mistake of keeping the whole situation secret, speaking, in daily reports, of the dreadful misery, the imminent collapse, the death-bed agony of the German nation.

The first effect of this policy was to shake confidence in Germany's power of recuperation, and consequently in the value of her currency. Who indeed would be fool enough to give credit to a man who insists he is on the verge of ruin, and will soon be a beggar sleeping in the gutter? The second effect was to lend plausibility to the legend of the "German camouflage". The contrast between official laments and the spectacle of rural prosperity and urban frivolity (which latter was pushed to almost scandalous lengths) led foreigners to the belief that Germany was ruining her state treasury to the advantage of private capital; so that, bankrupt as a government, she might still be in a position to renew her policies of commercial and military imperialism under a smoke-screen of poverty.

Add to that, a more and more conspicuous rise of German nationalism. Add to that the spectacle of von Hindenburg, in the very presence of a republican minister of war, renewing his oath of allegiance to his "most gracious sovereign", his "lord, king and emperor" (meanwhile drawing a fat salary from the Republic he is insulting!). Can you blame a Frenchman if he hesitates, if he refuses, to alter one tittle of a Treaty which insures him against renewed attacks from a neighbor whose bravery in battle and whose superiority in numbers are indisputable?

The Way Out of the Woods

NEVERTHELESS—hope springs eternal! Necessity, the laws of world economics, will, in the end assert their compelling force upon a spiteful and arrogant humanity, bewildered by the poison gas of international hatred and suspicion. The break in the cloud also is, to my mind, near at hand.

The gap between German costs of production and those obtaining in competing countries has all but closed for most articles; for others it has closed entirely. The outlook for German business is dark indeed.

Dividends that are dazzling when figured in German paper are reduced to the smallest fractions of one per cent in gold. A share quoted on exchange at four million above par is, in reality, pitifully low. During the period of easy money, manufacturing never attained more than 65 per cent of its pre-war output, and capitalists claimed at that time that the missing 35 per cent represented just the margin of profit. Now, in fact, German business must tremble for its bare existence: for the first time Germany sees the specter of general unemployment stalking upon her. The occupation of the Ruhr and the confiscation by France of enormous quantities of supplies (especially chemicals) have paralyzed whole branches of industry—some of them of the first importance. Everyone with an ounce of brains is aware that the poverty which today holds our middle classes, our brain workers, and the poorer laborers within its fangs, must seize upon a much greater portion of the population and with a still more grim ruthlessness before those people, whose minds, as the phrase goes, are "eternally of yesterday", will see their dreams come true: first, a loan, then agreement on reparations, then stabilization of the mark, then—well, the whole gamut—"toute la lyre"—in short. Our blind patriots, our Eberts, our Wirths, our Rathenaus, our Cunos—have picked on that string till it is worn out. The tune will never be played in that fashion. Things will not happen, because they cannot happen, in exactly that way.

The apex of madness has now, it seems, been reached: we can fall from it and break our necks; or we can, more intelligently, climb down to safety—but do something we must. France has played her last card—by entering the Ruhr. Germany has tried to trump this card with passive resistance (it is costing her terribly—thirty-six printing presses are turning out thousands of billions every day; however, some people still talk of stabilizing our currency!). Berlin's note of May 2d, which, in return for not unimportant concessions, had nothing more substantial to offer than the hope of a future loan, was another indication of the insanity of the moment. The answers from Paris, London, and Rome covered the government with a humiliation as great, and, alas, as well deserved, as the judgment passed upon it by the nine powers at Genoa after the futile prank of the secret Treaty with the Bolshevists at Rapallo.

IN order to recall the terrible penalties of War, and the spirit of the men whose sacrifices paid the price of the peace we now enjoy, we reprint this sonnet, "The Dead", By Rupert Brooke, the most gifted of the young writers who gave their lives:

BLOW out, you bugles, over the rich Dead! There's none of these so lonely and poor of old,

But, dying, has made us richer gifts than gold. These laid the world away; poured out the red Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene, That men call age; and those who would have been,

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.

Blow, bugles, blow! They brought us, for our dearth,

Holiness, lacked so long, and Love, and Pain. Honor has come back, as a king, to earth,

And paid his subjects with a royal wage;

And Nobleness walks in our ways again;

And we have come into our heritage.

What will happen now?

The inevitable, naturally! On June 7th Berlin made new and fairly reasonable proposals. France, however, declares she will not consider them till passive resistance in the Ruhr ceases. Germany replies that such resistance will continue till France withdraws her troops from the valley. The only hope remaining is that public opinion the world over will be brought to bear to force both governments to a more conciliatory frame of mind. It is a question of governments only: for the masses of the population, in both countries, so far as they are not misinformed, are ready for an amicable settlement. The essential steps toward the latter, as I see them, are these: Germany must cease resistance; and at that moment, France must withdraw her main forces, returning to the state of affairs obtaining the first day of the occupation. There must be a general amnesty for men now under arrest. France ought also to have the good grace to evacuate Dusseldorf, Duisburg and Ruhrort (the river ports), which she arbitrarily seized under the Briand ministry.

This much accomplished, the rest will be easier. Reparations (so far they remain unpaid, you see) are not the cause of Germany's distress. The payment of them will not restore French prosperity. These two countries, and all the rest of Europe, are suffering from the work of destruction carried out over a period of fifty months, with great zest and thoroughness, by one hundred millions of people.

Results?

The results are: that three-fourths of the nations of Europe are without a currency that has any value beyond their borders. Consequently they are unable to buy the products manufactured by the remaining fourth. Europe has split into two parts, one of which cannot buy, while the other cannot sell: gigantic expansion of the means of production; a shocking restriction of the means of consumption, a plethora of goods, an anaemia of markets. Such is the pernicious malady from which Europe is dying, meantime threatening contamination of the rest of the world. What saves the situation at the present time—in so far as anything can possibly save it— is the unbelievable consuming power of America.

The Situation Before Us

THE cure is not through loans—one country lending, a second promising to pay, and a third collecting interests. Only a Europe economically united, and conscious of that unity, only a Europe unhampered by dynastic intrigues, by patriotic animosities, by tariff obstacles, can hope for recovery. To such a Europe America would entrust her money. The wedding of the ore of Lorraine with the coke of the Ruhr would, for instance, create a cell of economic co-operation out of which the United States of Europe, the U. S. E., might eventually develop.

M. Poincare recently explained that France occupied the Ruhr Valley to force co-operation between French, Belgian, and German production. But the "collaboration immediate" which he demands cannot be limited to the sphere of industry. It would not endure were it to remain at the mercy of governmental politics, bureaucratic restrictions, ordinances, penalties, controls. It would have to include the Reparations Commission (Germany not voting, perhaps, but explaining her accounts and showing her balance-sheets). It would have to include the League of Nations. The rain of diplomatic notes would have to come to an end, conversations of business men (talking business) replacing them. After all, the issue is an issue between a debtor and a creditor, not between two enemies. Great Britain must somehow be called off European markets, finding her outlets in America and the East. She must be made to abandon any policy tending to oppose European peace and unity. The will to union! There is no other possibility for the restoration of Europe. If we fail to attain it, we cannot avoid chaos and a reconstruction along the lines of Bolshevism.

Is there a role for the United States to play in all this? One thing she might do is obvious. She might make the symptom-curers over here understand, and understand well, that America has neither sympathy nor money for states that are envious of each other, suspicious of each other, threatening each other with economic or military war.

"The U. S. A. will only help the U. S. E.!"

That should be the American slogan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now