Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Persistence of Prussianism

A German Publicist Claims it is Woven into the Fibre of German Institutions

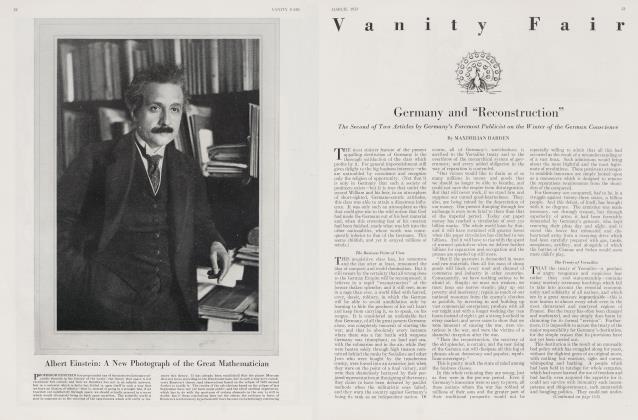

MAXIMILIAN HARDEN

EDITOR'S NOTE: It will be remembered that during the World War, a few honest, selfcritical voices were raised in the heart of the warring nations, on both sides, in protest against sentimental national self-glorification. Among these were Bernard Shaw, in England. In Germany, Maximilian Harden, editor of "Die Zukunft", turned the garment of military Prussianism inside out to show the seamy texture of the under side. During the war, Harden was not infrequently called the Bernard Shaw of Germany.

How Germany, despoiled of its true culture by the "vaulting ambition" of the Hohenzollerns, turned against them is a matter of common knowledge. Why she has recently reversed herself and turned back— temporarily, perhaps—to her old leaders, as represented by the recent election of Field-Marshal Hindenburg to the presidency of the German republic, was explained by Harden in a recent issue of Vanity Fair by showing how the force of the German tradition still holds in the older disappointed generation and also in the younger one which was nurtured on it.

In the present article, Harden tells of Prussianism: how it was formerly instilled into the German youth through educational agencies, and how it is being maintained, even in the Republic of to-day as a firm and unquenchable tradition of the German folk.

UNDER the pre-war regime in Germany, a boy was taught day by day in the schools that, until the Hohcnzollern dynasty assumed domination over the German states, they had languished in weakness, that from the Hohenzollerns every civic blessing had flowed: the faithful, strict administration; the progressive economic measures like that of pensioning old age and the system of poor relief; the fostering of art, philosophy, and science. All men of the ruling family were heroes and sages; all the women were angels of mercy. The private life of these princelings —secretly riddled with scandal—was held up as a model of almost Victorian propriety. The boy got the same teaching from his pastor on Sunday; and it was served up three times a day at meals in his home.

Here is a typical instance: the boy's aunt strolls down a path in the Berlin Tiergar ten and sees a royal princess, almost like a princess in a fairy tale, alighting from a skyblue carriage with silver lanterns and prancing horses and footmen in gold-braided livery. Her Royal Highness, herself, dressed quite simply in dark silk, like other mortal women, inquires if the other lady, too, is walking for her health; if she is married; if she has any children; what her husband's business is.

"A merchant, Your Highness," the aunt stammers.

"Oh, a very useful calling, for the protection and progress of which His Majesty is doing everything he can. A good day to you, my dear."

Really, she had said that, "A very useful calling" and "my dear." And after that she had honored the aunt, who always (of course, quite accidentally) walked the same path, three more times by speaking to her. Every time equally kind, every time with the same gracious farewell. It is not hard to understand that the aunt was considered, from that time on, as the most important member of the family. In a manner of speaking she was an old acquaintance of the Royal Princess whose patronage she might possibly invoke in case of need; and every member of the family thereafter who saw the sky-blue carriage with the steeds and the fancy braid and the silver lanterns and harness had the proud feeling: "There goes the noble lady of the ruling house with which, if only indirectly, we have a personal contact." And, because of a few goodnatured words from a benevolent princess, everything that had been said in the school textbooks and by the teachers about the friendly condescension and graciousness of the Hohenzollcrns seems to be confirmed a hundredfold.

The boy grows up and becomes a young man; he leaves the Gymnasiutn and serves his military term as a one year "volunteer." In his resplendent uniform, as a red hussar, a green chasseur, a blue dragoon, or in the dark blue uniform with broad yellow lapels of a Uhlan, he hears more than ever the glorification of the royal house to which he has given his oath of allegiance.

ALL his ambition and endeavour are now directed toward one goal—to be admitted to the officers' examination at the termination of his service period. It is true that he, whose father was only a merchant and not excessively rich, could not become an active officer, but he could become one of the innumerable reserve officers which the army needed in case of war.

The aunt is pushed into her nephew's service; however, she gets only as far as the driveling secretary in the service of Her Royal Highness who packs her off with the vague promise "to keep the matter in mind." But the nephew reaches his goal. He has even passed the examination: and then, of course, he belongs, skin and teeth, to "The Imperial Royal Service." On his calling card is printed "Lieutenant of the Reserves, Guard Regiment, Mr." With this illustrious title he signs letters, sometimes even his business correspondence. He appears in uniform at weddings, christenings and other ceremonies.

He now has "a regiment," is allowed (on certain festive occasions) to dine with the active officers at the officers' regimental mess. For all his deeds and misdeeds he is responsible to their court of honor and is called every year for drills and manoeuvres. To have been found worthy of these duties and of all the privileges which the officer in the German military enjoyed is his greatest happiness and his perennial pride.

TO AN American who may think that I am exaggerating all this, I would like to point out that the mere fact that he was a Jew and, therefore (in spite of good service in the Guard Cuirassier Regiment) could not be admitted to the officers' examination, cast such a shadow over the life of Emil Rathenau that this brilliantly talented man, who was a thorough monarchist, nationalist, and almost a militarist, joined the democratic camp after the flight of the Emperor, who had protected and honored him. He was finally murdered by some misguided scoundrels who did not recognize the real character of the man, who, in his heart, was a staunch monarchist and anti-republican. He often told me that nothing in his whole life hurt him so much as the fact that it was never possible for him to wear an officer's uniform, and yet no other desire possessed him so much as the one to become minister of the country which had refused to grant him the fulfilment of that wish.

Late in the summer of 1914, he organized the wartime administration for raw materials; and in October 1918, when the Hindenburgs and Ludendorffs were urgently begging for an armistice, he publicly demanded mass conscription and the strenuous prosecution of the war— that is to say, he was trying to step into the role of a German Gambetta. Both of these things he did in the hope of being rewarded with an officer's ranking. When this hope failed, he turned away from the monarchy, a disappointed man. When a man of Rathcnau's intelligence and general culture, a Jew, the son of a respected financier, Emil Rathenau, felt the way he did, it is easily imaginable how the average German valued those honors and distinctions which, to one not brought up in the Imperial tradition, appear to be just so much glittering trash.

So, whether lawyer or judge, merchant or engineer, professor or artist, mayor or doctor, our boy—now a man—always remained "Lieutenant of the Reserves," providing he has not had the incredible good fortune to climb another rung on the ladder of military distinction. His whole being was, and would remain, saturated with the spirit of the military monarchy. This was necessarily so; for if it happened that, because of something he did or failed to do, in the practice of his profession, he was called to account by the council of honor of his regiment, and if this council then saw fit to deny him his rank and the right to wear the uniform, he would be socially ostracized and would become absolutely "impossible" in those very places where he had formerly sunned himself in favor.

That such a distinction between a military and a civilian concept of honor was unfavorable to civic welfare requires no proof. Civilization may be defined as the strengthening of civilian pursuits. Even the noblest and most beautiful ideals and idyls of the days of chivalry are as superfluous, to a broker who deals in securities on the stock exchange, as a mediaeval suit of armor. If a man who sells cotton or coffee, or deals in grain, silk stockings, or oil, must consider that for a certain number of days in the year a sword dangled from his side and that he was therefore responsible every minute for every deed and misdeed to a band of sword-bearers, a state of affairs would naturally arise in which only the result, the outward effect, not the underlying principle of an action, would seem to be of any consequence. Such a condition in Germany easily degenerated into a hypocrisy strong enough to stifle all moral sentiments; and this hypocrisy was fundamental to the "strong-arm" Prussian morality.

Continued on page 116

Continued from page 48

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now