Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWoman and the Golfing Temperament

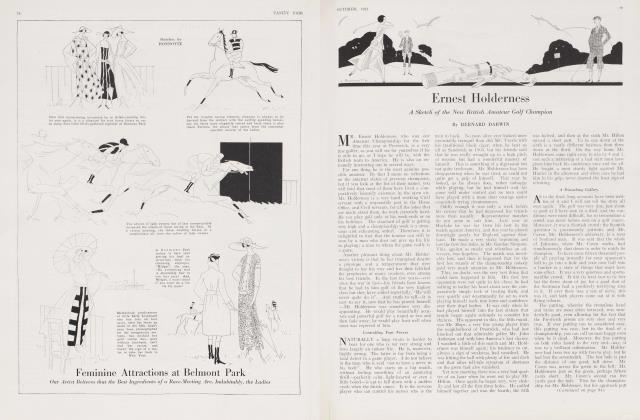

BERNARD DARWIN

WHERE I sit writing this article I can see out of the window the rain lashing furiously down upon a deserted golf course. Rivers are pouring across the green, and the bunkers are lakes. Clearly there can be no golf this morning.

And yet I am not sure. I am inclined to bet that presently I shall see two stout-hearted, mackintoshed ladies, dragging unwilling caddies behind them, fording the torrents and plunging into the oceans. This, in my experience, is just the kind of morning on which ladies seem to like to play golf. They are infinitely more courageous than men, who cower indoors and smoke pipes and read aimlessly the illustrated papers of the week before last. If the ladies have said they are going to play they will play, even though they have the other six days of the week to do it in.

There always seemed to me a strange appropriateness in the fact that the most pitiless rain in which I ever watched a big match was that in which two lady champions met. That was at Turnberry in 1921. when Miss Leitch and Miss Alexa Sterling had their historic battle in the first round. They, poor things, had to play, but it was just the kind of day to bring lady golfers out for pure pleasure.

This passion for getting wet and going through with it is only one instance to prove the general rule that women are much braver golfers than men. Men say that they find competition a bore and prefer a quiet game with a friend, but that is a most transparent pretence. The real truth is that we are horribly afraid of cards and pencils—that as soon as we have to keep a score, as apart from mendaciously inventing one, our knees knock together. To a lady golfer, on the other hand, a mere game is apparently quite insipid. Cards and pencils are necessary to induce a properly pugnacious frame of mind. If she is a bronze lady (I am a little uncertain as to what this may be) she is trying to return cards that will turn her into a silver lady. She is always doing something brave and fierce.

I have known men so supine and greedy that they rejoiced when their handicaps were put up, on the ground that they would thereby win more half-crowns, but no lady golfer would fall to such baseness. I shall never forget the flaming words with which I heard one lady begin her speech at a L. G. U. meeting, "Smarting as we all are from our handicaps having been raised . . ."

And yet combined with this ferocity there is a certain curious docility. Men revolt against any system whereby they are to be dragooned and jack-booted into returning cards in order to get handicaps. They say they can rub along very well as they are, making their own matches with their own friends, and the handicap committee can go to the devil. Not so the ladies, whose loyalty to the authorities is never shaken, no matter how many cards they are relentlessly ordered to put in.

It is only lately that male golfers have tried setting up systems of "scratch scores" and "National Handicaps," and it is unfortunate that our National Handicaps proved in their first year more or less useless because they were too soft-hearted. They were intended to reduce the number of entries for the Amateur Championship. Persons who had handicaps above a certain mark were to be excluded. But we were, I suppose, too frightened of being debarred ourselves, or had too great a fellow-feeling toward others in the same boat. So we drew the line at just such a point as could not possibly exclude anybody. Old A. and young X.—the two people against whom the whole formidable machinery had been directed—bobbed up again quite serenely. We sadly needed a little relentless, female efficiency.

On re-reading what I have so far written I become frightened lest I convey a wrong impression. I might be taken to mean that ladies were dour and solemn and gloomy opponents. Perish the thought! The two most light-hearted golfers of my acquaintance are two lady ex-champions, Mrs. Macbeth and Mrs. Dobell. "Fiery," Willie Park's famous old caddie, once said to Sandy Herd in tones of reproof, "Nae champion was ever freevilous". I don't think he would at all have approved of these two ladies. Yet there are no two finer fighters to be found anywhere, and Mrs. Macbeth's victory at Burnham over the invincible Miss Wethered was a really great achievement.

She has, I think, a very rare art, which American golfers possess, or at any rate cultivate. She can concentrate her entire mind on the stroke, and then relax entirely until the next stroke is played. It is what the Americans call "letting up" between the shots, and it is obviously a less exhausting and more agreeable plan than that of cultivating a fierce, continuous gloom throughout the entire match. Mrs. Macbeth often appears almost "freevilous" between whiles, but to see her settle down to a stroke that really wants playing is a liberal education. She has a golfing temperament to be bitterly coveted.

Perhaps it is because ladies have this great secret of playing at once light-heartedly and seriously that they are so fond of team matches as well as of medals. Men do have team matches, of a sort, certainly. The Bakers' Golfing Society plays against the Candlestick Makers, but there is wonderfully little enthusiasm about it. Once or twice a year, for my sins, I have to get up sides of this description, and I always expect at least two Candlestick Makers to send me telegrams on the last day unblushingly "chucking" me.

P. S.—Having written so far, I out down my pen and once more surveyed the links out of the window. The rain is still lashing down with undiminished vehemence, and I have won my bet. There, sure enough, go those two intrepid ladies, as I said they would. One of them has just waded into a bunker to play her ball out. Heavens! What a splash there will be! There it is, and most of the water has gone down the wretched caddie's neck. What bravery! What resolution! Who could withstand such a race?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now