Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLoud Speaker

Voices from a Forgotten Century Enliven, Momentarily, a Summer Home

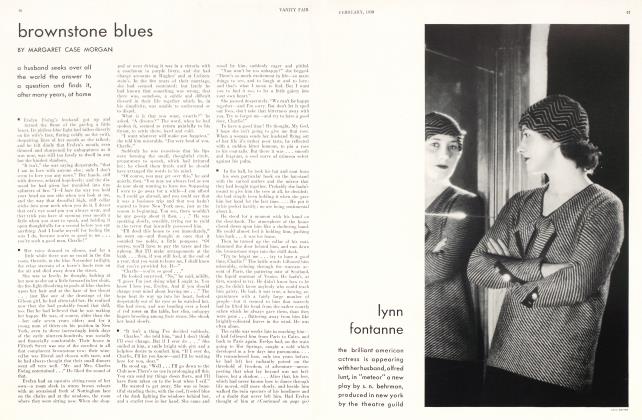

MARGARET CASE MORGAN

LIVING ROOM— one of those extravagantly simple living rooms which only the wealthy can afford— in a summer home on the south shore of Long Island. A warm dusk drifts from the garden and clings to the low ceiling, sof testing the accurate and perhaps too authentic lines of Chippendale and Adam grouped, like visitors, against the wall, blurring a little the warm cameos of colour that, in the sunlight, are yellow roses and larkspur in a silver bowl. GEOFFREY

GEOFFREY WINGATE is mixing cocktails at the Duncan Phyfe table. Slowly, he distills the lovely amber and pours it into little crystal goblets like tears. He is intent upon this, and does not look at BARBARA, his wife, who is at the piano, playing Debussy with a kind of soft despair.

The time is before dinner, on a July evening in 1936.

GEOFFREY: Your cocktail, my Barbara, weeping little honey-coloured tears of neglect—and so am I, because you are a rigorous woman. (He sighs.)

BARBARA: I'm not a rigorous woman, or any of the other things you find it so pleasant to call me, but I hale to see you getting yourself tight at six o'clock on a lovely evening, when you know perfectly well that dinner won't be announced for an hour and a half. (She assumes a hollow affability.)

However, don't mind me! You have plenty of time to drink your customary eight or ten.

Only you'd better not sit down, because you'll never be able to get up.

GEOFFREY (emptying his glass, and refilling it): The wonder is, my darling, that I am so frugal. You pick on me so continually, and nag at me with such increasing fervour, that I find my only escape in liquor—and a very agreeable one it is, too. (He nods brightly, and pours his third drink.)

BARBARA: You're getting that red look in the back of your neck already. And soon you'll have veins in your nose.

GEOFFREY: YOU should disguise your enthusiasm, dear, when you make such personal remarks. Let me have my red neck and my veins. You have your silver fox.

BARBARA (rising desperately from the piano ): Geoffrey, if you drag up that silver fox again I'll scream! Every time you know you're in the wrong you remind me of the time I bought the silver fox when we were hard up—

GEOFFREY: We still are hard up . . .

BARBARA (with spirit): Not so poor but what you can pay five thousand dollars a year to bootleggers . . .

GEOFFREY: For liquor which is consumed with incredible rapidity by that flock of puttypushers and defective actors I find drooling around here every afternoon when you give one of your justly famous "cocktail parties". Basil Swope, for example . . .

BARBARA (with a glance at the cocktailshaker): You'd better have fresh cocktails made presently. Basil Swope is coming here for dinner tonight. (She twists a rose in the silver bowl and looks at it critically.)

GEOFFREY (goaded): What, again! My God, have I got to watch that bus-boy shovel duck and potatoes into himself again at my table, besides drinking everything in the place? Barbara, I won't stand for it—I'll make a scene! I'm pretty apt to make a scene right here and now!

BARBARA (calmly): Oh, do it alone in your room first, Geoffrey dear. It's so much more likely to be convincing.

GEOFFREY: What's that goofer hang around here so much for, anyhow? You haven't fallen for him or something, have you? (Over the rim of his fifth cocktail his eye, encarnadined with suspicion, broods upon her.)

BARBARA (turning): Geoffrey, your entire conversation to me is made up of two remarks, used alternately, one in rapid succession upon the other; "How much did it cost?" is one, and "Why isn't dinner ready?" is the other. Any man who has anything else to say is such an entrancing novelty that I am very apt, Geoffrey, be clay in his hand?. (A lonely, perilous pool of tears is welling within her: she is pleasantly forlorn.) And anyway, how you have the face to begrudge my friends food in your house, when you pay thousands to bootleggers ...

GEOFFREY: Never mind the bootleggers! I guess I had to go without two cases of Bacardi so that you could have your silver fox . . .

BARBARA: And it's all I've had for a year! I go around in rags . . .

GEOFFREY: Yes, a rag from Chanel and a couple of dozen tatters from Bendel's.

BARBARA: Didn't I go out and cancel two dresses I had ordered, when you told me we were hard up, and about all the money you'd lost?

GEOFFREY: YOU did: which meant that you bought exactly six new dresses instead of eight. And you didn't have to have a silver fox. Lots of women . . .

BARBARA: Oh, my GOODNESS! I'm sick of hearing about that silver fox! Anybody with any setise ought to know that you can't wear a tailored suit without a fur, and I only had a brown fox and my new spring suit was grey. And anybody with any sense ought to know that you can't wear a brown fox with a grey ....

GEOFFREY: It isn't the silver fox that I mind—it's the principle! We can't go on spending fifty thousand dollars a year when I'm only making twenty-five, and the sooner you get that through your head the better. (Unnerved, he picks up the cocktail shaker and finds it empty. He looks around for a decanter, and seeing none, holds his head in his hands. BARBARA watches him through narrowed eyes.)

BARBARA: Well, I'm sorry you feel that way about it, because I bought something this afternoon as a surprise for you . . .

GEOFFREY (violently): A surprise! Asurprisc! (Hisvoice cracks.) How much did it cost?

BARBARA (dreamily ): I don't think I've ever heard Basil Swope use that phrase in all the time I've known him. (There is a pause.)

GEOFFREY ( perilously ):

How much did it cost?

BARBARA (waking from a delicious revery): Oh, about five hundred dollars or "something. But don't get so cross about it—it's worth it. In twenty years it will be worth five thousand. The man said so. (He rises, pacing the floor.)

GEOFFREY: Cross! In twenty years I'll be lying in a pauper's grave and you'll be melting down my gold watches to make teething rings for Airedales, and I won't care. But now I do, by gosh! Barbara, you can't seem to get it through your head that I've had a bad year! I've lost a lot of money! You've got no right to go and chuck away five hundred dollars on a lot of junk.

Continued on page 108

Continued from page 68

BARBARA (pleading, while reproachful tears tremble beneath her gentle lids): But Geoffrey, it's so lovely! Wait till you hear it . . .

GEOFFREY: What is it? What do you do with it?

BARBARA (in a thrilling voice, with dramatic effect): You hear George Washington speak with it.

GEOFFREY: YOU do what?

BARBARA: YOU hear George Washington speak with it. And Martha too. And Cicero, and Cleopatra, and William Shakespeare, just as though they were in the room. (She produces still another voice, a charming combination of mystery and awe.) It's a new kind of radio.

GEOFFREY(falls trembling into a chair): For God's sake! Can't you spend enough money on whatever you do spend it on, without going and falling for every piece of junk you see besides? As though you didn't fritter away every cent I can make . . .

BARBARA: You're just annoyed when anybody mentions George Washington or any great American like that, because you didn't have any ancestors in the Revolution and I did, and you just can't get over it! It's just a low form of jealousy.

GEOFFREY(simmering): Don't high-hat me! I suppose you've forgotten how you bragged about being descended from Paul Revere until you found out he was a blacksmith and then you denied ever having mentioned him, and said you were descended from the Marquis de Lafayette instead. Of all the . . .

BARBARA (preferring to ignore this): Oh, but Geoffrey, please listen! It's the most marvelous scientific thing, this new radio, and after all, everybody always said you were about the only man they knew who really understood the Einstein theory when it was so popular . . .

GEOFFREY: Well?

In the garden, the moon has risen. Through half-open French doors, the poplar trees are blurred in the night wind, the grass is laced with the platinum of a young moon. Its silver light breaks in little crescents upon Barbara, as she begins to speak.

BARBARA: Well, there's a theory, which some radio expert is working on, that since every sound that is made and every word that is spoken goes winging through the ether in a succession of sound waves for eternity, that somewhere at the end of these waves are lingering words that were spoken centuries ago. You understand that, Geoffrey?

GEOFFREY: Certainly. Go on.

BARBARA: And this radio expert has been trying to perfect a radio, very delicately balanced, which can so project itself into the vibrations of the air that it will be able to pick up these words of a century, or two centuries ago; so that we can hear, sitting in this room, Washington's farewell address to his soldiers, or

Cicero's orations, or Pocahontas talking to Captain John Smith . . .

GEOFFREY: Sounds like perfect damn nonsense to me. Where is it?

Barbara pushes forward a small table which has been hidden by a screen, and reveals the radio. It is the only clearly defined thing in the room, now filled with a haze of moonlight. She turns the dials.

BARBARA: YOU can put it back a hundred years, a hundred and fifty, or two hundred . . . sometimes, they say, if the air is very clear, you can go back as far as three hundred years, Geoffrey. What shall I turn it to?

GEOFFREY (shifting in his chair: the thing with its black, projecting face has made him uneasy): Oh, put it back a hundred and fifty years. You won't hear anything anyway.

She twists the dials again, puts in the plug. There is utter silence, save for the light whispering of the wind in the tranquil garden.

THE VOICE: I pray you, Martha, instruct the servants to set forth an excellent fine repast tonight. We are dining Kiashuta, the Seneca chief.

Another voice drifts wearily into the room. It is as though a cloud had strangled it a little.

THE SECOND VOICE: Oh fie, George! Another Indian? 'Tis common gossip in the town that General Washington's home is become but a meeting-place for Indians of the most bloodthirsty caliber. For have we not dined four sets of Indians on four several nights in the last week? I weary of your Indians.

GEORGE: It is but our duty, Madam. The Indians in these perilous times have suffered trials grievous beyond the puny comprehension of such favoured mortals as ourselves •. . .

MARTHA: It has but increased their gluttony, it seems.

GEORGE: Gluttony! There is a word I would tremble before, Madam, were I in your shoes. For was I not this very morning afflicted—afflicted, Madam!—to behold as much bacon stored in the smokehouse as would fill a fortification? A quantity, forsooth, in excess of husbandry. And I cannot but believe that it was provisioned with your full knowledge and consent, for you are a notorious hand for the fat of hogs, while I—

MARTHA: That bacon, George, is for the poor.

GEORGE: The poor, indeed! Then well may it find its way into our larder, for unless you retrench in your personal habits, Madam, you will not find a more penurious in a day's journey! The Indians, now—

MARTHA: Oh, have done with your Indians, George. I will sup them . . . but it must be in the company of another, for I expect Dr. Franklin to take tea with me, and I have it in my mind to ask him if he will stay and sup.

GEORGE : What, Ben Franklin again! Will you never have done with dining these sparkish and unabstemious gentlemen who consume a greater quantity of my Madeira than I could replace with all the gold in the Treasury?

MARTHA (coldly): They are in excellent competition, George, with you as host.

Continued on page 109

Continued, from page 108

GEOFFREY(in a voice of wonder): It's just like a quiet evening at home.

MARTHA WASHINGTON(continuing): . . . And when you speak of retrenching, George, it is well known that a lady of fashion cannot be seen at a levee two evenings in succession wearing the same plume. Why, is not Susan Boudriot a very laughing-stock, having appeared twice at the Embassy wearing the headdress of white ostrich feathers for which she set forth but a guinea three months ago? You bid me set an example, George, to the ladies of our acquaintance, yet you deny me the wherewithal to do it!

GEORGE: 'Tis true I profess myself a votary of economy . . .

MARTHA: Economy, forsooth! Parsimony were a better word. I have this month purchased but one white brocade silk trimmed with silver, a light blue sash with silver cord and tassel, small white hat with ostrich feather confined by a brilliant band and buckle; and for the ball at the French ambassador's—

GEORGE: Oh, Lord!

MARTHA: An egret, sir, pure and simple. For a woman may be a pattern of all the virtues, but she cannot wear a new turban of velours gauze without an egret. . . . Put down that claret, sir! Do you desire your friends, the Indians, to find you in your cups?

GEORGE: I do but fortify myself against a coming blow. The price of an egret, Madam—what is it?

MARTHA: A matter of three guineas. Far less than you have spent upon Burgundy and Madeira, and a sum, I vow, far in advance of that with which you provisioned me when you went off for three days, God knows where, witji that ill-conditioned rascal, Mr. Pinckney—

GEORGE: We did but hunt along the lordly Potomac, whereon I catched a duck which, had you practised a wifely economy, would have lasted us well into the week, and more.

MARTHA: 'Tis true, it would—hail you not seen fit to bid seven gentlemen come and dine that very evening who, with great fury and violence, set upon the duck until I was put to't to find aught for myself but gristle.

GEORGE(acidly): My balmiest consolations, Madam! But there is always the bacon.

MARTHA: Enough, sir, of the bacon! In the most solemn occasions you find naught but pretext to twit me about the bacon! (She sighs, an ex- quisite wisp of sound faltering down the ages.)

At the same moment, the connection breaks abruptly. Outside the windows, the poplar trees sway in a sudden wind. The sky darkens. A low rumble of thunder echoes among the hills. A storm is coming up.

BARBARA: Oh, I can't bear to have it stop there!

A flash of lightning freezes the room into cold silver, and is gone. But the voice continues.

MARTHA WASHINGTON: . . . Three times this week has the hogshead required replenishing, which fact in itself bespeaks your painful lack of abstinence.

GEORGE(mildly): I do but drink to carry off a cold.

MARTHA: I would liefer you succumbed. Yet you come by it honestly, the Lord knows, for was it not your ancestor, Sir John de Wessyngton, was Prior of the Benedictine Convent where, they tell me, the brewing of spiritous liquors goes on apace?

GEORGE(sternly): Do not attempt in so lordly a fashion, Madam, to twit me with my ancestors. It is in exceeding ill-taste . . . and yet . . . (his voice melts to a sickening pity) yet what can I expect, poor lady, from one descended as yourself from—er —Dandridges? A pallid procession of wizened county clerks and village parsons!

MARTHA: Rail away, George!

. . . But hush! . . I hear Mr.

Franklin . . .

A second flash of lightning severs the voice, and this time it does not return. At the same moment, the front door opens and closes, and there is the sound of a staccato arrival in the hall. Basil Swope has come for dinner.

Barbara rises quickly, switches on the lights in the room, and turns to greet him. All of her gestures are bright with welcome: her face alone is, ever so slightly, a mask.

BASIL (entering the room like a petal blowing downstream, in a series of little curves and rushes): Ah, Mrs. Wingate! Do I intrude upon your domestic scene? A radio, I perceive ... A radio ... a touch of home! (His glance bestows an accolade upon the radio) . . . "Household Hints", I presume?

BARBARA (looking at Geoffrey as she takes Basil's arm): Yes, Mr. Swope; I suppose you could call it . . . household hints.

She smiles charmingly, as they go in to dinner.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now