Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

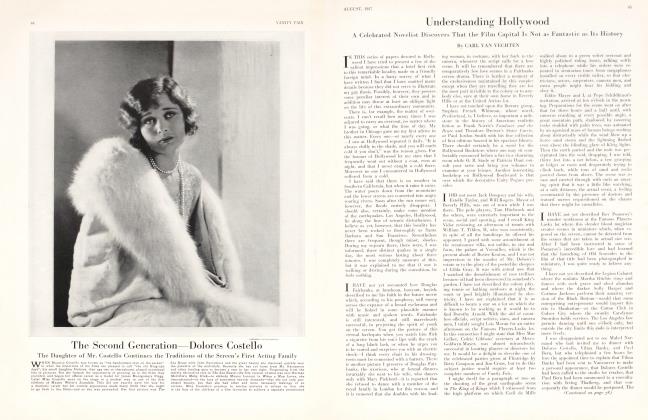

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHollywood Royalty

More Observations on the Film Metropolis and Some of Its More Prominent Citizens

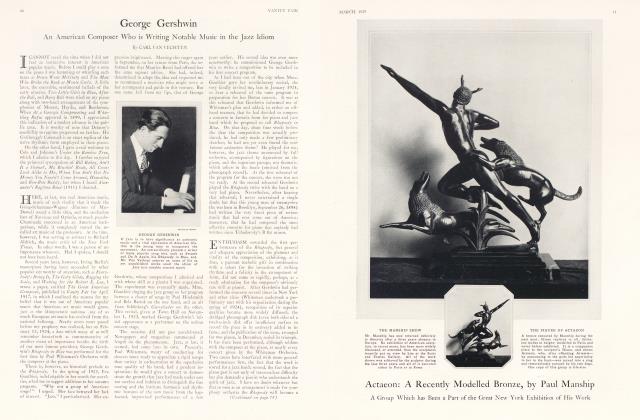

CARL VAN VECHTEN

MOTION picture star? are the modern equivalent of the kings and queens of romance. Not only do they command more attention than royalty ever did anywhere, hut also they wield a power which is unusual in any world, the power of satisfying wishes. Every great cinema company is so organized that any ordinary scene required by a script, and many extraordinary scenes, can he put together in a few hours, at most in a few days. It is the boast of Los Angeles, Hollywood (whatever inclusive name you prefer to give this great sprawling city which usurps several valleys, several mountains, even the seacoast) that it can supply almost any variety of flora or fauna, artificial or natural, for which there may be a demand. Within a few miles of any studio it is practically possible to arrange anything. Men with long beards, grown for the purpose, hopefully stroll the streets anxious to be at work. "Peddling the bush" is, 1 believe, the affectionate local argot for this curious occupation. Ladies breed St. Bernards, Dalmatians, and Borzois with the quite plausible intention of making them earn their living in the movies. 1 have no doubt that efficient mothers raise babies with the same end in view. It is possible to procure a dwarf or an Angora goat at a few minutes' notice. Furniture of any occidental or oriental period is available.

This condition makes it feasible for a star or a director with an imagination to satisfy any personal whim. If he desires, perchance, to watch a procession of elephants and camels, accompanied by nude Nubians with torches, pass his bedroom window, he is merely obliged to issue an order to that effect. A parade of mannequins, a Hopi snake dance, a flight of flamingos are all within reason.

THE acreage of the Lasky ranch makes it possible to erect sets there of a size that would considerably wrench the dimensions of the Paramount lot. When Jim Cruze, "on location," recently invited Scott Fitzgerald to spend an afternoon with him at this ranch, the author of The Great Gatsby asked if there would be quiet. Assured that there would be, he arrived to find himself in a complete French village with approximately two thousand peasants living there in native costume. "As 1 drove in," Scott, still in bewilderment, told me, "the band struck up the Black Bottom and the tricolor was hoisted!"

Apropos of this band, it is perhaps well to observe parenthetically that no scene of whatever put port is photographed without musical accompaniment, usually supplied by a harmonium and a violin. This music, gay or sad, always banal, is intended to inspire the actors to a more vibrant display of the appropriate emotions. King Vidor, however, informed me that he utilizes music to set the rhythm for a scene, more or less to time the action and to suggest the breadth of gesture. One star, not content with the thin harmonies which a pair of musicians are capable of producing, engages the best jazz band in Hollywood to set the saxophone free on her set.

Jim Cruze found time, especially at night, growing heavy on his hands at the distant Lasky ranch. Scott amused him one day. The next, according to report, he telephoned Tom Geraghtv to invite him to come out that evening for a bibulous conversation. Tom refused, but offered an alternative suggestion: "Why don't you call up a casting agency?" The suggestion was acted upon. Cruze telephoned the agency to send him a good drinker at once. "He must have a beard and wear evening clothes," Jim added reflectively. The man arrived hell-for-leather and was Jim's companion for several evenings. He was paid $io a day.

There is further the diverting story of the very prominent gentleman of business from New York who was receiving intensive entertainment in Hollywood. Something, it was felt, must be done to make every minute of his sojourn there agreeable, and as stars at work refuse to go out in the evening, the casting agency was relied upon to fill the chairs with attractive women at the large dinners. Every morning the host of the distinguished guest telephoned the agency to order ten, fifteen, or twenty beautiful gals in evening dress. These young ladies were paid $7.00 a day to dine with a man whom every one wanted to meet.

MANY affairs were arranged to honor the approaching marriage of Miss Stella Yeager to Mitchell Leisen, art director at the De Mille studio. Thus Jeanie Macpherson invited twelve of us to the Los Angeles opening of The Miracle, followed by a supper in the Cocoanut Grove of the Ambassador. At this supper, the table decorations, the music, the favours, the food were all elaborate reminders of the special nature of the occasion. I knew that Jeanie was much too occupied to plan any kind of party—the night before she had been detained with Mr. De Mille in the projection room until four in the morning deciding upon cuts in the vast number of reels of The King of Kings, for the script of which she had been responsible. How, I inquired, had she found time to devise this symbolic supper?

Jeanie laughed. "Why I didn't do a thing about it," she replied. "I haven't time. None of us has time. I simply told the property man that I wanted an original wedding set. As a matter of fact, all the decorations for the wedding, which is to take place Saturday at Cecil's ranch, have been designed at the studio. Even the bride's dress is being made there. We have," she added, "one of the best couturiéres in the world." It is characteristic of Hollywood that the bride and groom wore Russian costumes at this wedding and that the decorations and food were also Russian.

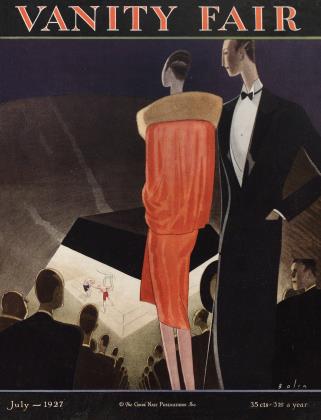

But perhaps it was when I glimpsed the movie stars receiving public adulation that I was reminded most strongly of the triumphs of the Caesars and the Romanoffs. I had once observed Jackie Coogan holding up traffic on Fifth Avenue for fifteen minutes while he stood on the base of the signal tower at the intersection of Forty-second Street. I had heard descriptions of Charlie Chaplin being mobbed in railroad stations. Nevertheless, somehow all this—and much more—did not prepare me for the marvels of a Sid Grauman opening.

When Old Ironsides opened at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre, Mrs. Lasky invited me to be her guest. Among her other guests at dinner were Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford and it was with them that I drove from the Ambassador to the theatre in Hollywood, a considerable distance. 1 was at first astonished by the number of cars on the boulevard, an amazing procession. Two miles away from the theatre the crowd stood ten deep behind the kerb, and for the whole of that two miles Mary Pickford (in a closed car—recognized through the window only by the illumination afforded by the street lamps) was cheered, not faintly, not half-heartedly, but lustily, even hysterically. Whenever the car was halted by traffic women pushed their way through the mob to peer through the glass at their idol.

When, at length, we reached the theatre the scene became prodigious. Searchlights streamed in all directions. A battalion of policemen vainly attempted to push back the seething hordes of gaping humanity, children, young boys and girls, old men and women. Frequently a suppliant figure would break through the ring to prostrate herself at the royal feet.

"Mary, let me kiss your hand!" "Let me kiss the hem of your dress!" "Mary, our own Mary!" These and kindred exclamations, with accompanying action, penetrated the resounding cheers of the multitude. Just off the sidewalk, in the lobby, a camera man ground away at his apparatus, backed by Klieg lights. From a safe asylum, a foot or two behind the camera, Frank and Bertha Case and I watched them photograph the emperor and empress.

WE entered the doors of the theatre three quarters of an hour after the time set for the show to begin. There we encountered Mrs. Grauman.

"We've been waiting for you, Mary," she cried. "I said wre wouldn't begin till you came even if we had to wait till midnight!"

As we walked down the aisle of the vast auditorium, a sea of faces craning in our direction—I happened to be by Miss Pickford's side, but I slipped back quickly to permit Mr. Fairbanks to take my place—there was a new demonstration: the entire audience rose and cheered. As we found our seats, the lights were extinguished and the band began to play the overture.

Perhaps no one else on this occasion received just the ovation allotted to Mary, but others did receive ovations, and they do at every opening night at Grauman's Theatres. The crowd always collects to applaud its favorites: Colleen Moore, Pauline Starke, Bebe Daniels ... A fellow with a megaphone stands next to the carriage opener to announce the baby stars, those too fresh in the industry to be easily recognizable. The Klieg lights glare on all impartially while each star is requested to pause on a chalk line as the camera man turns his crank. It is a scene that eludes the describer. It is as incredible and fantastic as anything in The Thousand and One Nights.

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued from page 38)

This phenomenon, moreover, on a smaller scale, may be observed on other occasions, at other localities in this Pacific coast town. For example, there are at least two "rubberneck" restaurants, one a modest tea-room, the other, the celebrated Montmartre on Hollywood Boulevard.

Madame Helene, a handsome, dark, buxom woman is the hostess of the tea-room on Verdugo Road, directly opposite the gate of the Famous Players-Lasky lot. The Metro-GoldwynMayer Company boasts a restaurant on its own lot—Miss Marion Davies is the possessor of an Italian villa and a personal chef on that lot—but, for the present, at any rate, the Paramount stars, for the most part, cross the street in costume and makeup to eat an avocado salad or a slice of Madame Helene's rich chocolate cake during the few short moments allowed them for luncheon. Here one may stare not only at all the officials and script writers of the Famous Players, but the stars as well. Eddie Cantor, engaged in making a picture under the direction of William Coodrich, eats his lunch with a person who bears an astounding resemblance to Fatty Arbuckle. Louise Brooks, Betty Bronson, Florence Vidor, Wallace Beery, Raymond Griffith, Ricardo Cortez, Bebe Daniels, Richard Dix, Esther Ralston, all may be seen at Madame Helene's. Consequently the doors burst with idle bystanders who come in to peer at these celebrated folk, even to make audible comments about them.

Madame Helene does not permit a new celebrity, however humble, to slip in unannounced. As I entered her tearoom with Lois and Gladys Moran she greeted me with the remark, spoken loudly enough to reach the ears of those in the far corners. "Mr. Van Yechten is my favourite novelist." Presently I heard her explain to Geoffrey Shurlock and a group of writers that among my books she had not quite decided whether she preferred Helen of Troy or Galahad.

Montmartre is fashionable at lunch time on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays. On these days such stars as have the time and inclination come to dance and such part of the Hollywood lay world as can manage to secure a table comes to rubberneck. On the day before I attended services there Pauline Starke had engaged a table for us, but when we arrived the crowd behind the rope trying to crash the gate was so strenuous that we were very nearly crushed before we managed to squeeze through. Women almost in hysterics with a desire to glimpse Greta Garbo toying with her grape-fruit or the Duncan sisters negotiating spaghetti, sometimes attempt to bribe Paul Perot, but that superb maitre d'hotel brushes aside all offered gratuities with audible scorn. "Madame," he announces, "I cannot be bought. Please don't do that."

In some astonishment I considered the psychology of these various mobs. Here was no trumped-up, press-agented exploitation. Here could be no actual sense of curiosity. These famous people lived in this town. Their faces could be seen on occasions like these, or others, almost every week, some, almost every day. One would expect on the part of the populace either indifference, surfeit, or else actual distaste. One would presuppose that envy might enter into the public attitude. It would even seem possible that this mob might stone these spoiled children of fortune in their rich dresses, their priceless sables, their pearls and emeralds and diamonds set by Cartier. Not at all: the crowd bows low and kisses the hem of the royal garments. They adore, they worship, these modern divinities. Incense is burned and laurel boughs waved. Hollywood did more to convince me t hat democracy is an unpopular form of government than all the editorials II. L. Mencken has ever written.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now