Sign In to Your Account

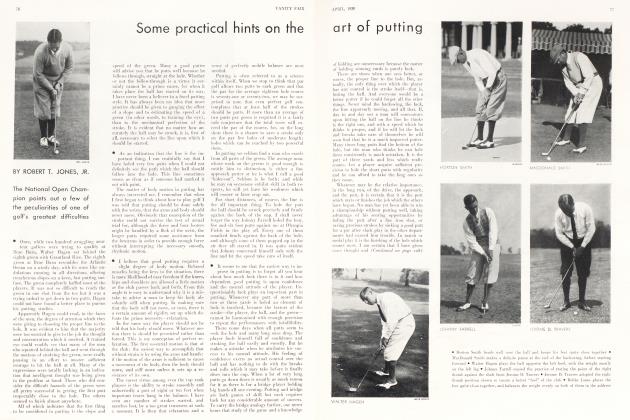

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe enchanted coffer

CLAUDE ANET

The story of a little iron chest, a red shield and a dynasty that survived the Hapsburgs and Romanoffs

■ I was strolling down the wide and lively" streets of Frankfort-on-Main. It is a busy and prosperous city, offering many attractions, notably one of the finest museums in Germany. Frankfort has also had its great men. When one has the honour to be a man of letters, one cannot forget that a Prince of our republic was born here, and spent the years of his youth and adolescence here.

I never pass through Frankfort without paying a visit to Goethe's house. His family was solidly established in the esteem and prosperity of the community when Wolfgang was born, and the house is that of a comfortable bourgeois of the XVIIIth century. Here he was awakened to life. The first ineffaceable emotions that stirred in his breast*, he experienced in this house. The first young girl he loved was called Gretchen. Do we not find this name in Faust, and is it not little Gretchen of the red hands who will preserve longest the name of Goethe from oblivion?

But was young Goethe aware, while he was manoeuvring his puppets and serving his dramatic apprenticeship in the attic under the paternal roof, that in a part of the town remote front that which he inhabited, in the ghetto, where doubtless he seldom had occasion to go, there was a child a few years older than he whose name would become celebrated? It is very likely that for forty years at least, Goethe never heard this name pronounced that one day would resound around the world. And when he did hear it, he was already at the height of his glory, and could not divine that the Jew who was hut occasionally mentioned outside of Frankfort's business world would be more universally known than Goethe himself, to whom all Germany had payed homage.

This Jew was of the most obscure origin, and born into the utmost poverty. At an age when young Goethe lived in luxury, Anselm Mayer thought of becoming a rabbi, and was studying the Torah. In a yeshivah in the little town of Furth, he knelt, prostrating his thin body forwards and back. Subtle discussions on the problems which the Torah propounds, they say, develop intellectual shrewdness. Anselm Mayer did not become a rabbi, but was lucky enough to be sent to work in a Hamburg bank. Later he returned to Frankfort. Goethe was studying law in Leipzig when Anselm Mayer married a woman as poor as himself, and opened a shop in the ghetto. Over the door of this little shop, he hung a distinctive sign, "like a trade mark," a shield cut in stone, and painted red, a Roth-schild.

At that time there was a ghetto in Frankfort. It has disappeared long since. Or rather, I believe that all Frankfort has become Jewish, and that if there were any separate quarter, it would need to be constructed for the Christians.

Anselm Mayer's wife kept the shop, while her husband hawked the countryside as a peddler. The country was not always safe. But Anselm Mayer was armed only with an umbrella, which never left his hand. Gradually he widened the scope of these journeyings, and established contacts in Frankfort. In this family, a penny was a penny. "There are no small profits" had been the slogan •of already large and prosperous houses. At that time there were small profits only for this clever and avid couple, but nevertheless Anselm Mayer managed to set a little money aside, and this money in turn was put to work. He was energetic, kept his commitments, and he was also fortunate in his business dealings. In time he became a power in Frankfort.

■ It was only then, I believe, that he bought the house in the Judengasse which is still standing there, one of the curiosities of the city. Its acquisition must have made a great impression at the time, because small as it was, it was the house of an already successful man, of a property owner. It is just the same today as it was then... piously preserved by the powerful family of the barons Rothschild. The street has changed its name, but the house is there, with the shield—Schild, on which the red has worn away, sculptured over the door. Next to 'the Rothschild house is a similar one, under the sign of a ship—Schiff. The Schiffs have also been heard of in the business world, but mostly in America, while our aristocratic family of barons of the red shield have always remained in Europe. When Anselm Mayer installed himself in the Judengasse, he had already earned the respect of men of affairs in Frankfort. Then came the troubled times unloosed on Europe by the French Revolution. The thrones of Europe began to tremble on their foundations.

It is interesting to note that epochs of great political or social crises do not frighten the Jews. They have seen too many such times since they were driven from their country two thousand years ago, to wander, buffeted about, over the world. The independent Jew having no ties, extricates himself with little trouble from convulsions in which fixed and crystallized social classes struggle helplessly. His lively, subtle intelligence quickly realizes how profits may be realized from situations which present themselves in such stormy hours. That is why the Jews have often been accused of creating these very disturbances, and of sowing the seeds of revolution. I do not think that this accusation is well founded. In eastern Europe there is a numerous and povertystricken Jewish proletariat. Nothing could be more natural than that revolution would be welcome there. That was clearly demonstrated in the Russian Revolution which broke out twelve years ago, and which is not yet over. But the prosperous merchants of Western Europe, and of America, the bankers of Wall Street, the City, and the Bourse, have absolutely no wish to destroy a social order which has enriched them, and over which they exercise a powerful influence.

■ However that may be, Anselm Mayer knew how to profit by the disorders that followed in the wake of the French Revolution. The Sambre and the Meuse armies led by Hoche, crossed the Rhine. The little German princes, not at all anxious to endure the rigors of war, fled. Some of them needed money. Where were they to get it, if not from those clever fellows in the Judengasse who always managed to have it in their coffers? Anselm Mayer loaned money against safe securities, chateaux, villages, farms, which no matter how severe the storm, could not melt away.

One of these princes, the Elector of HesseCassel, had an enormous gold reserve. How was he to get it away? Where could he leave it in safety? He deposited it with the bankers, but for the most part, with Anselm Mayer, in 1794. Two millions florins passed into the hands of the former peddler. When some years later the prince elector of Hesse-Cassel returned for them, the two million florins had produced several millions more in the clever hands of Anselm Mayer. During all the period of the revolutionary wars, he employed the money thus gained, not for the service of one cause, one party, one country, but to his own advantage. He loaned to the allies, and to Napoleon. He clad the soldiers without bothering himself to ask the color of their uniforms; he provisioned them without looking under what flag they marched. Amazingly well-informed, he doubled his fortune because he was the first in London to know the result of the Battle of Waterloo. In 1815, he was one of the richest men in Europe, and by the grace of the Emperor of Austria, was granted the title of baron for himself and his issue.

This story, this essentially modern fairy tale, in which a demi-god appears in the picturesque garb of a peddler armed with an umbrella, I recalled while walking through the narrow rooms of the little house in the Judengasse. Nothing was changed here— there were the wooden staircase, the pine boards, the earthenware stoves, the small windows, the backroom with the blackboard at which Anselm Mayer checked his accounts. Certainly there was nothing in this poor and barren interior to aid the imagination in reconstructing the astonishing and magnificent past of this man. But my visit was not ended.

Continued on page 94

(Continued from page 61)

My guide at length took me into a little side room at the rear of the house, away from the street, where there might have been, if not thieves, at least prowlers, or perhaps brawls and riots. There he showed me the coffer in which the first of the Rothschilds was wont to lock up his recently acquired possessions:—the handsome florins still redolent of the little country farms from which they had just come, correctly indorsed notes and drafts, receipts with reliable signatures, and without doubt some jewels and precious stones; everything and anything that had a value, and on which money could he loaned.

This solid, narrow iron coffer was not clamped to the ground. Two men might easily lift it. It was hardly larger than the trunk writh which the modern woman travels. Nevertheless, what treasures have not come out of it?

While I looked at it curiously, there arose before my eyes palaces rearing their splendid fagades in all the capitals of Europe; princely villas reflected in the still waters of lakes and rivers; lordly chateaux in shadowy parks; extensive hot-houses for the cultivation of orchids, roses, and rare plants; millions of pheasants, partridges, rabbits nourished for the shoots; race-horses galloping down turf and track. The most beautiful pictures in the world: Van Dyck, Memling, Raphael, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian, Frans Hals and Watteau grouped themselves around this bare iron coffer; pearl necklaces and glittering rivers of diamonds overflowed its rough sides. Then Anselm Mayer, first baron of Rothschild, appeared in the shadow of the dim room, shabbily dressed like the peddler that he was. He had not forgotten his umbrella.

"My children's children will marry princes and dukes," he said in an emotionless voice, "hut the blood of Anselm Mayer will be stronger than theirs, it will make itself known no matter what the name they bear. The kings will disappear; the elector princes that I have worked for, and who have made me rich; the Bourbons who are of the past already; the Bonapartes, the greatest of whom I have seen; the Hohenzollerns who are allpowerful in Prussia; the Hapsburgs, who ennobled me, and the Romanoffs who own half the earth. The dynasty that I have founded will survive them, and the spoils of their palaces will adorn the houses of my children."

"There is hut one power in the world today. It is . . .

Anselm Mayer struck the iron coffer with his umbrella, and the coffer answered in a metallic, golden voice.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now