Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowReading, the new vice

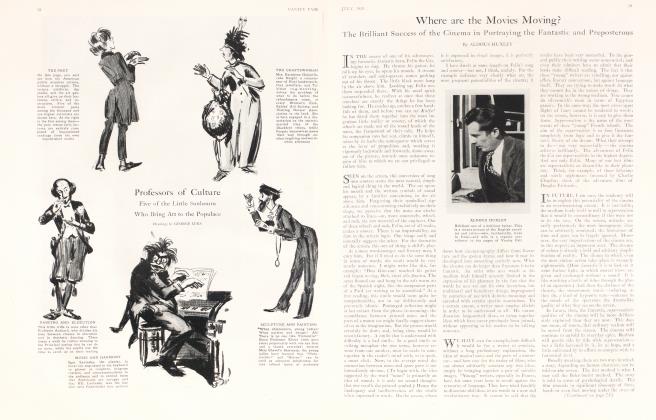

ALDOUS HUXLEY

I believe that the level of culture in America and Europe can be raised to something approaching the pitch at which it stood among the Greeks at the time of Pericles. But the means I would employ to achieve this end are precisely the opposite of those which educators and intellectual uplifters usually suggest. They would multiply reading-matter and cheapen print, I would restrict the first by the simple expedient of making the second prohibitively expensive. A tax of four or five thousand percent on paper, imposed simultaneously by international agreement, in every country of the world, would do more, I am convinced, for the popularization of culture than any number of libraries and cheap editions, encyclopedias and anthologies.

Culture is not derived from the reading of books—but from the thorough and intensive reading of good books. Now, the cheapening of print has everywhere resulted in the wholesale production of inferior reading matter and the formation, among almost the whole of educated humanity, of a habit of superficial and inattentive reading. It follows that any large increase in the demand for readingmatter can only be met by an increase in the supply of bad writing. Confronted by reading matter which is not trivial, or unimportant, the hardened (or rather softened) reader of magazines and newspapers either skims superficially across the pages, treating sense and significance as he has always treated nonsense and triviality, or else turns away in disgust and fear from a kind of writing which demands from him, as good writing always demands from its readers, that he shall make an effort to follow and understand, that he shall actively use his intelligence and imagination. I have called our habit of reading too much, and reading nonsense, a vice. And a vice it really is, strictly comparable to the vice of taking morphia. Reading—the reading of newspapers, magazines and fiction—is our universal opiate and deadener. We read, not to stimulate ourselves to think, but to prevent ourselves from thinking; not to enrich our souls, but to kill time and bemuse awareness; not for the sake of being fully alive, but in order to be less vitally conscious of the surrounding reality. Cheap printing has flooded the world with a respectable substitute for alcohol and cocaine. Reading which should be the food of the soul has been degraded into a spiritual drug. If politicians had any sense, they would add newspapers and magazines to the list of degrading intoxicants, the traffic in which should be forbidden or at least strictly controlled.

My own suggestion provides, I venture to believe, the simplest, perhaps the only solution of the problem. A four or five thousand per cent tax on paper, universally imposed, would have the following beneficent results. It would put a stop to the spiritual drug habit and retransform reading from a dangerous and degrading intoxicant into a valuable food of the soul. It would make the masses take an interest in the best that has been thought or said and would tend to raise the level of culture throughout the world.

The immediate effect of a four or five thousand percent tax on paper would be to drive practically all periodicals out of circulation. A daily newspaper of the size now considered indispensable would cost about a dollar or its equivalent in other currencies. Very few customers would buy at this price and the proprietors would be driven either to suspend publication altogether, or else, if they wanted to go on selling their wares at the present rate, to reduce their journal to the dimensions of a single quarto page, on to which it would be physically impossible to cram more than a very limited amount of insignificance, triviality and nonsense. At from three to fifteen dollars a copy, the weekly and monthly periodicals would simply fade out. So would the vast majority of sixty-, eighty-, and hundred-dollar novels. Books would become as precious as they were in classical and mediaeval times, would be treasured with a pious care and studied with that literally religious fervour, which was so characteristic of the seekers after culture in past ages. In this age of abounding rubbish, we simply cannot understand the awed reverence with which Dante, or even the much later Milton, could speak of books and their contents. Only when books are at least as scarce as they were in Milton's day will modern man recapture that passion for literature, that religious respect for culture which distinguished the men of another time. The word "highbrow" has become in our age, which is the age of cheap printing, libraries and encyclopedias, a term of mockery and insult.

Continued on page 76

Continued from page 47

The prohibition of unlimited reading—for my proposed tax would amount to a prohibition—may be trusted to produce the same psychological effects as did the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. The Eighteenth Amendment turned thousands of previously sober American citizens into inveterate drinkers. They drank because it was illegal to drink, and then because they liked it, because they had formed the habit. In the same way, my prohibition of promiscuous printing would turn thousands of previously illiterate or magazine-loving men and women into inveterate readers. For the forbidden is always the desirable, and we value most highly what is rare and hard to come by. Pass my proposed measure into law, and the bootlegging of Shakespeare will become one of the most paying of professions. Desperate book-runners will land cargoes of Homer and Dante on the shore of lonely coves; and armed policemen will patrol the land, hunting for illicit paper mills and hidden stores of Plato and Spinoza. In a word, the so-called Problem of the Popularization - of Culture will thus be automatically solved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now