Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTalking up—and thinking down

CLARE BOOTHE BROKAW

How to be a success in society without saying a single word of much importance at any time

Too much has already been written about the dead or dying art of conversation. Drawing room cynics and critics of society assert that the fine art of persiflage and repartee, of making epigrams and bons mots, of Pope's "feast of reason and flow of soul" which flourished until Nineteen Hundred in the salons of France and England, received its death blow at the dinner tables of the modern capitals. For this demise, in New York at any rate, many good and plausible reasons are given: the materialism of modern interests, the mad, mechanical pace of the Twentieth Century, and the subsequent dearth of leisure. These same critics (who, like the poor, are always with us) claim that all conversation has deteriorated into the veriest small-talk—talk, in fact, which is not only small but even microscopic.

Nevertheless not even the briefest, the most hurried of theatre party dinners is to be achieved without some exchange of words. This exchange, for want of a better term, is still called conversation. But the difference between it and the conversation of say, fifty years ago, lies in the fact that it is no longer spontaneous, inspired, fortuitous or pleasureably accidental. Nor is it, on the other -hand, as it was in the .heyday of the continental salons, predetermined, studied or skillfully manoeuvred. This only happens nowadays when a guest who has taken his bath before dining out arrives at the table with a pretty quip on the tip of his tongue because divine inspiration has come upon him in the tub.

Conversation has assumed, one might say, the status of a national game—one with very definite rules, requiring in skill and subtlety something less than ping-pong and more than baseball.

The purpose of the conversational game is to be able to talk freely, and, at length, in a sprightly and voluble manner throughout an entire dinner or, in more gruelling instances, throughout an entire week-end without, by any chance or misapprehension, saying anything whioh everyone present does not already know. Any infringement of this obligation to reduce conversation to its lowest common denominator, any expression of an original opinion, or the revelation of a hitherto unsuspected faot, is immediately classed as a breach of the rules—a foul blow, as it were, struck below the social belt, the dreadful penalty for which is exclusion from the social ring.

To talk even in monosyllables requires words, and words require a certain amount of ideas, which is where the new art of conversation begins—'and ends. Some foreign critics have said this is because the mental equipment or ideational content of the average New Yorker consists of a rather forcibly circumscribed smattering of knowledge about five or six topics. .

These topics are, in the order of their importance, golf, the stock market, prohibition, the theatre and a frank discussion of such persons (not present on this occasion) as figure in the social activities of the conversing guests.

In more intellectual circles, remarks about modern art (not later than Rodin, however), of modern thought—as personified in the Shaw of Man and Superman or Dr. Will Durant, or grand opera, as sung by Jeritza, may occasionally he introduced with safety into the conversation. It is also permissible in these more rarefied milieus to drop a carefully considered word about Hemingway or Brancusi. But with the mention of James Joyce, Proust, Picasso, Antheil, Spengler and Einstein you are completely disqualified, a self branded high-brow, a social pariah. That is, of course, unless you have introduced their names merely to add a little good natured ribaldry to the conversation. But, when you mention them, smile.

The cardinal rule to be remembered is that all contemporary conversation must be limned or suggested against a sparkling background of sex. It must be threaded, shot through with naughty implications whose multitudinous off-colours range from a polite pink at the lobster-course to a passionate purple at the grapes. It has been estimated by expert diners-out that nine-tenths of all discourse today deals directly or indirectly with sex. The tenth part should convey, by subtle conversational alchemy, the impression that whereas you are dealing ostensibly with another topic, you are really thinking of sex. If you are able to convey this impression, your conversational batting average will be 1000.

But let us examine more closely these topics whioh comprise so completely the curriculum of modern converse.

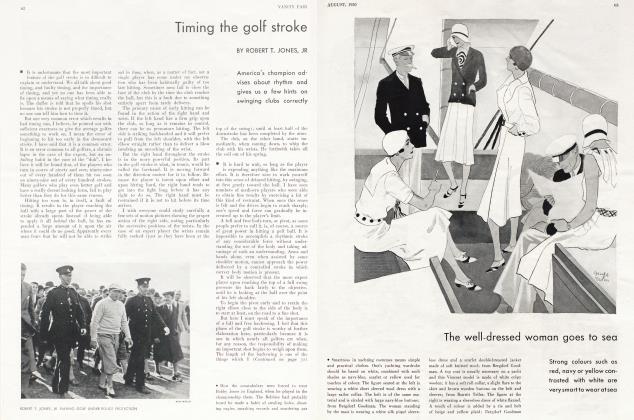

There is, and probably always will be, golf. This comfortable subject may be dwelled on at length—providing always you do not claim to have made two holes in one during your golfing career, or turned in a score -under seventy. This would instantly classify you as a man of imagination, and in a society which may relish a charming fairy-tale now and then, any other form of whimsy or fantasy will place you beyond the social pale. Golf, moreover, is sure-fire, since its quaint terminology provides ample opportunities for double entendre.

Then there is the stock exchange. Unless you are very close to Mr. Morgan or Mr. Hutton (you probably are: aren't we all?) it is considered an affectation not to vouchsafe a strong opinion on the immediate trend of the market. After this you will be listened to with bated breaths if you launch forth into a protraoted and winsomely modest account of how you participated in, or manipulated a pool in International Drawstring, or sold 1000 shares of Associated Vanilla short in a bull market. At this point some unsung philosopher among you will remark that a bear makes money, a bull makes money but a hog never does. At the continued reiteration of Wall Street's bull activities, the conversation can be trusted to take a more delicate turn, and by this time, the finger bowls should arrive, if, indeed, they have not already been brought in.

Prohibition, as a dinner table topic, has been worn somewhat threadbare (except in the suburbs), but if you attack it with sufficiently passionate (although equally threadbare) arguments, emphasizing each debatable point with another draught of Pommery & Greno or Three Star Hennessy, and dramatic pauses, you may nevertheless convey the impression that you are a person of daring intellectual convictions. It is more fashionable nowadays to discuss less weighty phases of Prohibition: your bootlegger, not his prices, but his bank account, his taste in shirts and cravats, and the intimate details of his family life.

The theatre has become a rather dubious talking point. Everyone knows that with the advent of the talkies (you must always call them "squawkies", "balkies" or "mawkies") the theatre has completely gone to pot. However, every season provides one scandalous play not yet closed by the police, and you may safely enquire—without breaking any rules of the game—of someone who does not know the answer "How do they get away with it?" You will then, of course, quote a few lines from the play, or repeat -a joke from a musical comedy—Flying High provides plenty of material this season.

The field of personalities undoubtedly supplies the richest crop of conversational morsels. You must, and this indeed is a fine art, be able to slander, criticize and ridicule mutual friends and acquaintances who are, of course, not present, in such a manner that when the whole delicious mess is reported back to them as it invariably is, you can satisfactorily explain and plausibly deny any derogatory reference attributed to you when cornered for an explanation. Furthermore, at the next dinner you attend you can decry, and libel, your late hostess who caused you acute embarrassment by repeating the remarks you made about her predecessor. If you are a hostess yourself this should cause

Continued on page 85

(Continued from page 39)

you no grief. For a dinner party or a week-end which is not followed by a post-mortem is worse than dead.

Of course, there are subsidiary topics with which to embellish these general themes: the high rents on Long Island, unusual bridge hands, backgammon contests, pedigreed pups and race-horses, the idiosyncrasies of the Newporters as retailed by privileged visitors to that social sanctum sanctorum, and, once in a while, a desultory discussion of a prominent political figure, provided again that his private life is sufficiently under suspicion to make his public career worth discussing. It is wiser, however, to leave politics, domestic and otherwise, strictly alone—at least until the ladies have left, although it may be remarked at table—with commendable esprit—that Gandhi is the colored fellow (isn't he?) who is putting salt on the British lion's tail; or that on his account Isadora Duncan's brother walked down to the Battery for salt, whereupon another guest (who heard the remark before) will ask "Why wasn't he arrested for assault and battery?" Or you may wittily explain that Mussolini is the Italian who levelled a tax on bachelors because he wanted "more Woppy and less whoopee". Mr. Hoover is a poor subject for a society which was completely spoiled by the antics of Warren G. Harding and the taciturnity of Calvin Coolidge. The latter's disappearance from public life brought an end to an era of anecdotes as remarkable for their prolixity as Mr. Coolidge was for his reputed conversational aridity.

However, with the aid of these five or six topics, the dinner will be already over, and at this point the ladies leave the gentlemen to their liqueurs and cigars. The latter, relieved of the presence of the gentler sex which imposed a certain restraint and the use of rather involved circumlocutions, gleefully fall into their anecdotage,

while in the other room, those women who are not at the moment powdering their noses, begin to prattle solemnly on the A B C of feminine discussion: Adultery, Babies and Clothes.

Possibly all this may be most depressing to anyone old fashioned enough still to believe that conversation should be provocative, informative and, on rare occasions, brilliant. But if you are well versed in the fine points of this new game or art of conversation, there is satisfaction enough in following its simple rules.

The pleasure you may have once found in a delicious bon mot, in an epigram as neatly carved as a bit of Chinese jade, in a flash of repartee, bright and bitter as a sword thrust, you recapture in hearing the dear familiar ring of an oft told tale. The delight you once took in hearing or propounding a new theory, which unfolded before the mind's eye like a bit of unexplored landscape, you now experience in that prophetic thrill which comes when you are able, beyond a doubt, to predict every phrase, every word that will issue from the lips of each person present.

Then, too, there is the thrill of adventure which sweeps over you when you allow yourself to tremble on the verge of an opinion, when an epigram you never utter is dangerously foreshadowed, or when you hang perilously close to that abyss—the advancement of a theory. For the short space of a second your hostess looks at you with dawning horror, as if you were about to confess to the murder of your broker. Then she breaks out in a smile of approval and relief, when you withdraw from the brink and say, instead, the expected, the commonplace, the conventional. In short, with practice and persistence, you may become a master of the wise-crack, a candidate for an interlocutor's degree. You will gather the social fruits of your conversational victories at all the dinner tables in town and country.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now