Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPolitical diplomats

JEFFERSON CHASE

How diplomats pour the oil of persiflage in the wheels of government, thus avoiding frequent political explosions

After ten years on the wagon, America has suddenly gone diplomatic. Not since Woodrow the Well-Beloved suddenly discovered that he was hot stuff on the typewriter, has the nation experienced such a rash of Notes, Memoranda, Conversations and Communiques. Great crowds wait breathless to know what the Secretary of State told the Patagonian Minister; hungry international bankers camp on the White House steps and gather hope from a smile from the third assistant to the fifth special assistant to the President's Private Secretary. Strong men hug the evening papers to their breasts and wrinkle their brows over whether the Jews are going to accept the moratorium or the Armenians are going to insist on revising the Treaty of Versailles. International gold movements are scrutinized with an all but medical care, and are heralded by a flurry of Notes. Baseball, Transpacific Flights, Tree Sitters, Bicycle Racers and Marathon Dancers are eclipsed by what the Acting Secretary of State may have meant when he was reported to have said, "Put less soda in mine this time, Mr. Ambassador." Wall Street waits with breath bated for the suckers who never bite. Word comes that the French are proving obstinate and U. S. Steel Common drops 3½ points; word comes that the French have given way and U. S. Steel Common drops 2½ points. American Tel & Tel earns enough on Transatlantic telephone calls to pay an extra dividend. American Can wobbles wildly with every report from Moscow and Tokyo. And the world's statesmen—or, as their opponents would say, politicians in office—enjoy the privacy of a gold-fish.

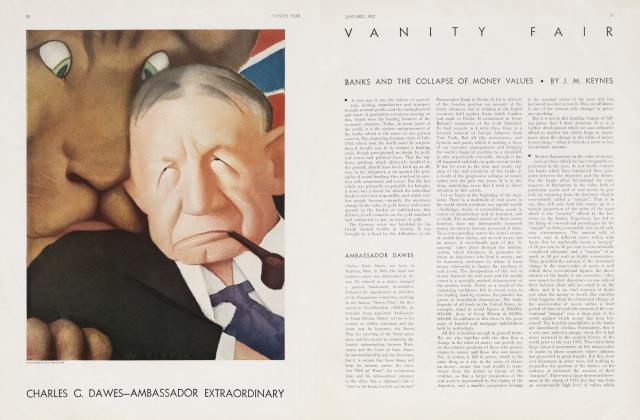

When Ambassador Edge goes to bed at night he has to make sure that there isn't a reporter under the bed. One morning General Dawes found three foreign correspondents swimming in his bath pretending they were sponges. Ambassador Sackett in Berlin doesn't dare squeeze a grape-fruit without making sure that it doesn't contain a dictaphone, and Secretary Stimson is said to have shot a special correspondent of the London Daily Mail who disguised himself as a grouse in order to discover what Ramsay MacDonald was talking about on the Scottish moors with our eminent foreign minister.

Strange indeed have been the expedients adopted to conceal from the press that there was anything happening. Stimson threw everybody off the scent by leaving for Italy on a slow boat just before the lid blew off German reparations. At that he is said to have been serenaded at the dock at Naples by a quartet composed of the Foreign Ministers of the Little Entente and of Poland. Ambassador Dawes pretended he was organizing the new Chicago World's Fair, and now it transpires that he was getting Al Capone's consent to a temporary suspension of war debts. Ambassador Sackett concealed what was going on by employing American slang in diplomatic conversation. "That isn't worth a hill of beans" was an expression he employed to mislead the German correspondents, who have a high regard for beans and who presumably thought that a hill of beans would be worth ever so many Reichmarks. At one time London and Washington were giving entirely contradictory and entirely convincing explanations of one and the same thing. The diplomatic epidemic became contagious, and Governor Franklin Roosevelt of New York tried to take part in it, under the impression that it was anybody's fight. He wrote an ultimatum demanding a moratorium on Canadian waterways, and he still doesn't know whether he slipped on a banana peel or on a State Department communique.

It's been a great show and it's been a pity that the public hasn't understood it. The wonder is that there have not been louder and funnier laughs. When you get a group of practical politicians and another group of professional diplomats and a third group of politicians trying to be diplomats and a fourth group of diplomats trying to be politicians, you get action. Now, action is the soul of politics, but the bane of diplomacy. A completely diplomatic world would be very polite but nothing would ever happen in it; it would live in a state of courteously suspended animation. There is nothing that shocks a diplomat so much as to be confronted with the shamefully naked exhibition of a fact demanding action.

Politics is always playing the Hairy Ape at the diplomatic tea-party. Hirsute, sweaty, gross and ill-mannered, politics interrupts the soft murmur of "two lumps and lemon, please" with a brutal demand for fire-water. Life is like that, as Duse told D'Annunzio. Things don't stay put. People get tired of paying taxes, or they want to eat or they want to travel around, or they want to give their children a chance in life, or they want to get their wife a new hat, and they suddenly jump up and nip the diplomats in the ankles. Politics doesn't speak gently. It isn't used to courtesy. It sees what it wants and makes a bee-line for it, whether it is a moratorium or a war or a new tariff or an immigration law.

Diplomacy, on the other hand, is always trying to play chamber music in the midst of the political rough-house. It goes around patting the snorting and suspicious politicians on the back and reminding them that other people want to eat too, or that Great Britain has a bigger navy than we have, or that France has a bigger army, or that we can't get at Russia. Diplomacy can always think of fifteen excellent and irrefutable reasons for doing nothing just now. Next year, perhaps —or in five years—or when Stalin dies—or when the Labor Government falls—or when the depression hits the French tax-payer—but not now, oh dear no! Why! it would upset this, and that would have to be taken into consideration. Then there's this treaty we signed seventy years ago, and the other government refuses to consider changing it. And you can't complain of that, because that's exactly what we are doing ourselves in the Philippines. And we'd better not protest about this, because in another fifty years we'll probably be in a position where we will want to do exactly the same thing. So the diplomats thread their way, lowing melodiously, through the herd of bellowing politicians.

This is what happens. The Honorable Mortimer Groener, lame-duck Congressman from Missouri, is paid off for making the Great Sacrifice by being appointed EnvoyExtraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Republic of Catalonia. The head of the Republic of Catalonia is Hernando Lopez, who has been in his day both a farmer, a smuggler, a revolutionary and political boss, and has made all four professions pay like a bank. The sardine merchants of Catalonia get angry at the large quantity of American sardines being sold in competition with Catalonian sardines, and inflict a law making it impossible to import American sardines into Catalonia. The Americans retaliate by searching every ship of Catalonian registry for liquor, and tipping off the bankers that Catalonia bonds are about as enduring as the bonds of Hollywood matrimony.

This rapidly produces a crisis. The honest Republican sardine-catchers of California wrap their dirty fish in Old Glory, and demand that we send the navy to make the Catalonians eat our oil-soaked minnows. The Catalonian banks and shipping lines go to Premier Lopez and tell him they fear a social revolution unless vigorous measures are taken to nationalize the American oil companies in Catalonia. The American oil companies get wind of the scheme and pass their property over to a dummy British company, which brings the British Navy to hold annual target practice for the first time in history within ear-shot of the Catalonian capital. Then everybody gets tired of losing money and "diplomatic conversations" begin between Minister Groener and Premier Lopez on the subject of sardines.

The Catalonian Foreign Office sends a note in which it offers to admit American sardines if each sardine has been inspected by a Catalonian veterinary for hoof-and-mouth disease. Minister Groener hits the ceiling and roars at his diplomatic secretary, "Tell those wops to go to hell!" So the diplomatic secretarysits down and writes note in the following tenor:

(Continued on page 69)

(Continued from page 36)

"The American Minister lias the honor to acknowledge Your Excellency's Note of the umpteenth ump in which Your Excellency very courteously offers to modify the present sanitary measures of inspection now applicable to sardines of American origin. The American Minister greatly appreciates the spirit of accommodation which characterizes Your Excellency's generous offer but desires to point out that it is not in accord with the spirit of the Minister's suggestion that American sardines should be admitted free of duty. The American Minister does not. therefore, feel that he is at liberty to communicate to his Government the substance of Your Excellency's Note or to recommend that the American Government bring to the attention of the interested bankers Your Excellency's desire to contract a loan, unless assurance Is forthcoming, etc., etc., etc."

When this slap on the wrist is deciphered by Premier Lopez's Foreign Minister, Senor Lopez goes out and gets drunk, utters a few "Carrambas!", has a quarrel with his mistress and disinherits his eldest son. Then, much refreshed, he returns to his office and orders the trembling Foreign Minister to tell the American dogs that he will not admit a single dirty sardine unless the American Government will make the Prohibition agents look the other way when the "Santa Veronica" docks next Tuesday.

So the Minister for Foreign Affairs writes sadly—he is majority stockholder in the Catalonian Sardine Monopoly—to the American Minister:

"Most Illustrious Excellency:

I have the honor to refer to Your Excellency's highly esteemed Note of the so-and-so in which Your Excellency recognized the generous spirit of accommodation which the Catalonian Government endeavors to evince in its dealings with the world.

I have been directed to assure Your Excellency that the Catalonian Government is prepared to modify its suggestion for a special veterinary regime for sardines of North American origin to the extent of applying the ordinary tariff rate to such sardines, if the North American Government is able to offer assurances that vessels of Catalonian registry will not be subject to extraordinary measures of inspection and customs treatment by the officials of the North American Government.

Accordingly, I have the honor to suggest that, effective on the receipt of your assurance that Catalonian interests will be treated with the same spirit of accommodation by the North American Government as the Government of the Catalonian Republic is prepared to accord to North American sardines, the two Governments agree to apply no extraordinary regime to the vessels or produce of the other, or words to that effect."

When this strikes the American Legation, Minister Groener exclaims: "Whoopie! I knew the old son-of-agun would back down. He shipped a hundred cases of Haig & Haig on the 'Santa Veronica' and the hull damn Coast Guard's waiting to mop it up at Sandy Hook. Tell 'em Okeh, my boy."

So the diplomatic secretary laboriously grinds out three pages of official foolscap, paying high tribute to the magnanimity of the Catalonian officials, and the Minister sends a cablegram to a friend of his in Washington: "Tell Bill to lay off Veronica this trip. Wire Joe sardines okeh." And the Secretary of State is informed by cablegram: "Catalonian Government today withdrew sanitary measures prohibiting import American sardines, which are now admitted under general tariff subject duty ten pesos per kilo."

That's the way the world's business gets done. If the politicians were left to handle it, we'd have a war inside a year and a world-war in two years. If it were left to diplomatists every nalion would wall itself up behind castiron egotisms and discriminations, polite and stagnant. Each off-sets the other and each has his part to play. But the next time you pick up the paper and read that the State Department has sent another vigorous note to Whoozis on account of the gold situation or the wheat glut, take a neep behind the "I have the honor's" and "is in substantial accord with's" and "venture to suggest's" and see the real starting point of that note: a group of hot, red-faced and reasonably angry men, one of whom says at length: "Bill, tell old Blank that we're damn good and tired of all this fooling around and that if they don't fall in line right away . . ."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now