Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSo many doomsdays

WILLIAM HARLAN HALE

A line-up of the prophets who try to sell us a dozen kinds of doom, each variety more gruesome than the one before

Again—this time on October tenth—the world failed to come to an end. The predictions of Robert Reidt, official prophet of doom, were once more inaccurate. The cataclysmic event has not—up to the time of this writing—taken place. But of course we have no assurance that it may not occur, even before the bottom of this page is reached.

In our northern nations, a great tradition of deathly prophecy has developed; and now, in a day of especial doubt and frequent despair, the tradition flourishes as never before. It is not just the Adventists, the Hamilton Fishes, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the more morbid versions of Evangeline Adams who have current visions of the specter of ghastly doom. No, the tradition has taken hold of critics and philosophers, who, in mounting numbers, busy themselves with writing up their particular brand of ruin. The one assumption common to all is that ruin is just around the corner; as to which corner that may be, the prophets wildly disagree. Some see ruin as coming from the Fifth Avenue of capitalism; others, from the Union Square of Communism; to some it comes from the Broadway of decadent pleasure, and to others from the 168th-Street-hospital-block of medical need, of pathology, of artificial means to prolong our tired life.

Not only do the corners around which ruin is supposed to come differ widely; the methods of describing them do the same. On one hand you get the terrific volumes of Oswald Spengler (champion doomster of the ages) ; and on another the wild and woolly diatribes written by sub-editors of revolutionary weeklies. On one side you get the scientistphilosophers broadcasting their doleful message to a listening (and collapsing) cosmos; on the other you get the Gabriels of Grand Street, whose trumpetings are loud in the studios of their cronies, but who remain, to the rest of the world, mute and inglorious.

Death and damnation, you know, are terrors particular to the North. Doom is a horror native to our Gothic mind. The southern peoples never took these things very seriously. The Lower World and all the other furniture of classical post-mortems—these were little more than unusual and depressing features of a formal landscape. And even when Christianity brought in Purgatory and Hell, these dour appurtenances never attained their full ghoulish glory until they had been transported northward across the Alps. The world of Valhalla and of pre-Wagnerian thunderings immediately dramatized these visions for all they were worth. To the people of the south, the devil was a conveniently remote and rather ludicrous old satyr, hopping around in a bath of sparks and brimstone; but to the northerner—and especially to our early New Englander—the devil came closer and closer until, horrible in stature, he stood entrenched in every hayrick, and hid himself in every guest bed-room.

And so we got our Doom. We feared it so much that we thought about it all the time. Now we have begun to fall in love with it. How, indeed, would a serious monthly magazine survive if it did not print regular prophecies on the downfall of western culture? And how would the book trade proceed if it did not pour forth a continuous stream of deathly Revelation, ably indexed and well bound? The half-serious and favorite old theme, "The world is going to the dogs, you know," has given way to literary barrages with such blazing titles as Breakdown: The Collapse of Traditional Civilization. The old symposium habit, made a vehicle of benign optimism during the 'twenties, now becomes a means to broadcast the galloping damnations of a troop of contributors over an awed America. There's a volume just out under the uncomfortable name of Our Neurotic Age, in which a dozen intellectual giants discover that everything we do is pretty absurd, that we are a lot of morons, that most people are either diseased or crooks, and that there isn't any hope.

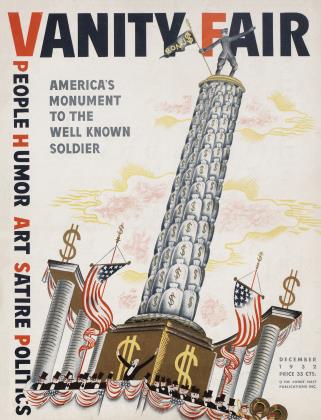

Abler propheteers of doom are the editors of the new magazine Americana, already famous for its savage cartooning. They state their editorial platform: "We are Americans who believe that our civilization exudes a miasmic stench and that we had better prepare to give it a decent but rapid burial. We are the laughing morticians of the present." Shades of Wesley, Calvin, Savonarola, John Huss, Saints Peter and Paul—here's ecstasy for you!

But the apostles of wreck, wrack, and ruin are of a hundred gradations of severity: some sigh and wail, others boil and blister. If we are to try to find out something about their startling brand of mind, we ought to classify them. Perhaps they fall into four progressive divisions. First are the Prophets of Amiable Decay. A step further on in melancholy are the Prophets of Sad Decline. Further along in the domain of solemn preaching are the Prophets of Hopeless Collapse. And at the extreme left wing of prophecy are the Prophets of Immediate Smash. All of them, it is to be understood, have their private appointments with destiny. So many doomsdays!

The Amiable Decay men are, at least, themselves amiable fellows: they do not take themselves very seriously. They are the Norman Douglases (Goodbye to Western Civilization) and all the others who see modern life as a cramped degeneracy, overworked, crowded, unaesthetic, sexless, in no way equal to the gusto and freedom of days long ago. They are a sentimental lot, eminently worth reading or listening to. Anatole France bewept the passing of the pagan world, as our Benjamin DeCasseres beweeps the passing of Rabelais. All, of course, in America beweep the passing of beer. They are the constant worshippers of "the good old days". Most of them think that the good old days were those before Prohibition. But before Prohibition they (under James Huneker's leadership) thought the good old days were those of Paris in the middle of the century. And in Paris at the middle of the century, the good old days were thought to be those of the Middle Ages, or of Africa when unexplored, or of anything that was romantic and daring and therefore far gone. The reason, according to these gentry, why the present is decaying is a simple one: it is not like the past. What charming sentiments! And what grace ful dinner-table conversation!

But when we meet the Sad Decline men we step on to more serious ground. These are the philosophers of pain. These art' the Spenglers, scholarly, still urbane, but absolutely convinced that our civilization has concluded its period of blossom and must, like any flower or any man, wither and die. To prove their assertion, they bring out vast collections of historical fact, showing all manner of comparisons. Their devotion is not to a sentimental past, hut to a great philosophical Fate. Needless to say, they are almost always Germans.

The Hopeless Collapse crowd are more intense. Doom isn't a matter of logic with them: they are not even joyful about it. But they have developed a high lingo of damnation. They have discovered Futility—and that discovery is the only thing they regard as not being futile. It lends itself especially well to poetry. Young Harvard men eat it up. Some flee to Tahiti, and try to get away from it all. Other collapsists stick it out in our midst, and are Difficult. Like the Americana editors, they all know that we are all goners.

But give them some sort of enthusiasm for the current vogue of revolution, and they turn from Hopeless Collapse morticians into Immediate Smashmen. They are likely to become American Marxians, utterly unable to see anything in this country except the spectacle of upper and lower classes which are fighting each other to the death. Their ceaseless visions of gory strife have naturally made them a hit morbid, and very hard to talk to. In fact, they are impossible to talk to. They see a surging American proletariat, and know that in a couple of months it will fro about smashing the existing system of horrible petty-bourgeois tyranny. They see the whole structure just about ready to go swooping down with a grand roar of bursting timber —and never stop to realize that in America there is practically nothing discernible which might resemble Professor Marx's bourgeoisie or proletariat. But of course there is no arguing. Cataclysm is their catechism; they must start with ruin.

(Continued on page 67)

(Continued from page 35)

All of which leaves some of us out. Or does the current fashion of doom compel you? Of course, you may take your choice as to dooms; but really do you find it necessary to believe in any one at all? You may accept the doom offered by the philosophers, the neurologists, the scientific men, who amply prove that there is no hope for us, and that either civilization or the human race, or both, are collapsing. You can have the doom offered by the extreme political prophets, who see American culture smashed (and some hazy utopian scheme suddenly shoved in to pinch-hit for it). You can have the doom offered by intellectuals and dreamers, who just continue the good old tradition of telling us that we are going to the dogs. Well, we have been going to the dogs for a long, long time. In case we have already arrived at the dogs—that, of course, would settle the issue.

And yet, we still seem to go on: we produce an astonishing wealth of books and sew'er-pipes, good paintings and bad music, electronic analyses and alcoholic syntheses, chromium-nickel lamps and tin pianos, epics, partridges, and ocean fliers. Is it only the honey optimism of Bruce Barton, William Lyon Phelps, and Robert W. Service that keeps us going? Or that of Irving Fisher and Roger Ward Babson, sometime promoters of limitless prosperity? Barely! It's just people like that who make us want to fly to doom, as to a happy relief.

We seem to go on because our realization that Prohibition has tried to wipe out decency does not keep us from hoping that decency may return; or because we still hope for another Cleveland, Another Walt Whitman, another Delmonico's, even after reading Professor Spengler; or because we still hope to make our son the greatest Yale fullback since Ted Coy, even after we have been told that the manhood of the race is hopelessly on the downgrade. After we have read the Breakdowns, the Collapses, and the prophecies of immediate revolution and chaos, we still put on our new London tails, parade our "conspicuous waste" through the theatre lobby, and bow to the gardenias at the Opening Night. We learn that the structure of civilization is about to crash, and we still build three-story mansions with plenty of rooms for our children's children, and even extra garage space for that other car we'll buy when the next great boom begins. Obstinate race!

And on the bottom shelves of our mansion's library, row on row, in tall dog-eared procession, stand the books and tracts and magazines which were the Baedekers to doom.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now