Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe screen

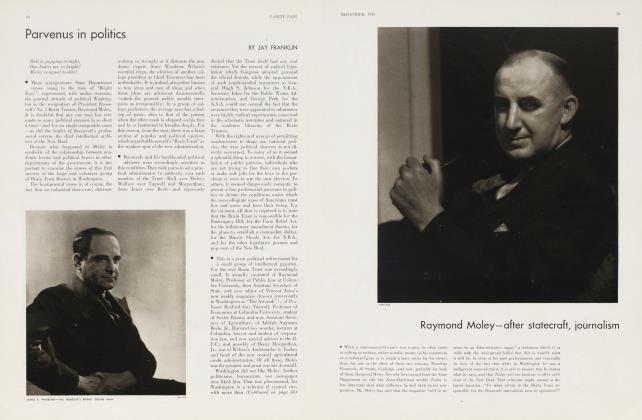

PARE LORENTZ

A DEPOSED EMPEROR.— Those of you who ever sat in the drafty pews of the old Provincetown Theatre and were almost blown out of your uncomfortable seats by the tom-tomming that drove Emperor Jones into a gibbering idiot, probably anticipated, as I certainly did, something exciting from Paul Robeson in the movie version of the O'Neill play.

I had a genuine feeling of anticipation before I went to see the picture, because it was produced under what were, if there is such a thing in the theatre, ideal conditions.

Two young producers bought the play and made it in the old Paramount studios in Long Island. Thus, whatever mistakes they might naturally make, one felt that we would be spared typical Hollywood errors: a mulatto chorus routine in the Emperor's palace, or, as conceivable, Johnny Mack Brown or Clark Gable in blackface, cast in the role of Brutus Jones.

The director they hired, Dudley Murphy, has long agitated independent ideas in movie circles, although he has only Hollywood pot-boilers and a three-reel curio, made years ago, to his credit. Yet here was a director with ideas; a famous manuscript; a natural choice for the lead, Paul Robeson—who already had done the part to great acclaim in London and in New York; a tried author, Du Bose Heyward, to work on the scenario; and a general freedom from the salesmen, bankers, vice-presidents and supervisors who invariably smear their hands over the best celluloid Hollywood produces.

The result, to my amazement, was an unexciting and indifferent motion picture.

■ EXTRA-CURRICULAR SCENES.— A snap judgment would indict Du Bose Heyward and Director Murphy for all the short-comings in the production. In order to make a full-length picture, the scenario writer took the early incidents in the life of Brutus Jones, and carefully, if prosaically, wrote them into a preface to the original play. O'Neill indicated the Pullman porter's past by a few paragraphs of dialogue; in the picture, we began with a stagey revival meeting that seems to be part of last season's Hall Johnson Negro show, Run Little Chillun; and at the very start, Brutus Jones seems a great deal more superficial than O'Neill's Emperor.

From his home town, Heyward took Jones to Harlem, and here again Director Murphy showed his provincialism by having his Pullman porter hero dining and dancing in the Cotton Club, a proceeding as phoney-looking as it was implausible.

Throughout these scenes, Brutus Jones becomes merely a brash rooster of a Negro, taking his fun where he finds it and boasting as he goes.

There is an incredible scene in the President's private car and then, finally, for the first time, we have a legitimate bit of drama, when Brutus kills his friend Jeff in a quarrel following a crap game. This is also the first sequence that has any bearing on the incidents in the original play.

The subsequent chain gang shots, the escape, and Jones' usurpation of the throne of a tiny kingdom, seem more like a part of a Gus Hill olio routine, than a melodrama; not so much because of actual comic writing, but because none of the people appear real or important to Brutus Jones, so that his strutting and boasting seem so many unanswered cues for the interlocutor.

This indifferent writing and worse direction was a matter of judgment; the eight-scene play would have made oidy three reels of film at the most; they had to lengthen the show some way in order to make a major production of it. They took the most cautious way; and then didn't do justice to their work.

However, once they get Brutus Jones on the throne, the Messrs. Heyward and Murphy never once maltreat a line or situation, and the original play comes tagging along, completely intact, behind this hodgepodge preface.

SUB-HOLLYWOOD.— Without going into technical details, the timing and sound of the drum, and the dissolves in which Jones sees his past, in drum tempo, rising around him in the forest, are far below the photographic standard one may find in any hum-drum Hollywood movie, and for two lessons: the Astoria equipment is old-fashioned, and so is Mr. Murphy.

Yet, while mistakes in judgment and lack of technical skill emasculated the picture to some extent, it didn't explain why, in the closing scenes, Emperor Jones still remained unexciting. After all, it has not been many years since a Negro movie would have been banned entirely from the screen by Elder Hays. We seldom have a picture which has a direct emotional dramatic situation without Janet Gaynor or Constance Bennett or some other queen stepping bang into the show, making it just another movie. And Emperor Jones is not that.

So, after blaming the director and author completely, I suddenly realized that Paul Robeson, a fine figure of a man. and a singer who is completely satisfying, is equally culpable.

(Continued on page 56)

(Continued from page 47)

He has two faults that make his Emperor a wax figure and not a living, fearful man. One is the self-conscious acting usual to actors of his race and to precocious children; the other, similar fault, is the over-broad gestures, grimaces, and surface emotional show peculiar to concert singers who have to portray a regiment of soldiers charging a castle wall and keep in tune at the same time.

THE RIGHT TRACK BUT THEWRONG HORSE.—There are few times one has any undue excitement in this business and I was not only disappointed in Emperor Jones, but genuinely sorry the show didn't come off. While I have no particular interest in the finances of Krimsky and Cochran, they can completely howl over the inbred producing system in Hollywood by making courageous independent pictures, and, indifferent as it is, I hope they make a profit from this production—they're on the right track.

I have a feeling that today the play itself couldn't be exciting in anything but a drafty little theatre. It is not a full-fledged show; it is O'Neill of thirteen years ago, and it can't be stretched any further than the narrow limits of the Province-town stage. It hasn't the poetry or the stride of the later O'Neill plays. It is a fugue for drum and actor, and the drum is in no way as exciting as it was in 1920.

ULTRA PROFUNDUS.—I do not think it is funny when an actor dresses up in grandpa's old bobtailed coat and pearl grey derby; I do not think it is amusing to realize that in Johnson's time the Royal family of England blew their noses on their fingers; and above all, I do not enjoy dramas which are designed, like Mr. Hearst's newspapers, for People Who Think.

Thus, admitting one of the most striking productions ever turned out of a studio, and as splendid a performance as Leslie Howard could give in an ambiguous and fatuous role, I nevertheless found Berkeley Square a beautiful bore.

There is absolutely no fault in the picture, Berkeley Square, except the fault in the original play, i.e., it is a cheesy profundity fashioned out of A Yankee In King Arthur's Court, dressed up in polite English.

THE REAL McCOY.—A press agent, two playwrights, and several comparative strangers all warned me that I would be bowled over by my first exposure to Elizabeth Bergner. Consequently I went to see one of her earlier performances in a picture called Ariane, expecting to find anything from another Swedish somnambulist to a new twig from the Maedchen, or Hepburn-Dietrich tree of acting.

The picture is in English, but the photography is in French, and represents about the worst order of that adolescent French art. The leading actor was brought back to life by some Satanic laboratory business; there is no other explanation; because he proved to he none other than the old English Smithfield of silent days, Percy Marmont.

I saw the picture in a tiny projection room that had a tin roof, upon which a hurricane was roaring all during the picture. Yet Miss Bergner, in a very few moments, had me reduced to a soft pulp.

If she does appear this winter in Hollywood, as she is now supposed to. I think she will accomplish in one week what no manner of criticism could accomplish in a year: she will remove the glacier age of actresses from the screen.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now