Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHollywood on parade

HELEN BROWN NORDEN

HISTORY RUNS AMUCK.—The past couple of months have witnessed a big run on historical pictures. It may be that actually there were not more than three or four of them, but it seemed to me as if I were snowed under by epics. In all of them the main characters were British, so I have come out of it with a fine Oxford accent myself and go around saying "dark" for "clerk", lapsing with the greatest of ease into Cockney, " 'Ere's to the Queen, Gor bless 'er!" whenever I get a chance. The trouble is the chance doesn't come very often in the course of an ordinary conversation.

Since in profound ignorance of English history I am second to none, I really stand in no position to comment on the authenticity of these films. But I will not let that stop me from doing so. And anyway, I know what I like. At least three of the films were released last month, but because of their importance they still merit notice.

MOTHER INDIA.—In two of the pictures, the action takes place, for the greater part, in India: Lives of a Bengal Lancer and Clive of India. In both of them, British imperialism is shown up, although quite unconsciously, in a pretty unpleasant light. Naively devoid of social conscience, they glorify the unquestionable right of one nation to plunder, subjugate and hold in complete thralldom another nation—particularly if the other nation happens to be of a different color from that pale Nordic hue which denotes those beings divinely ordained as superior to their fellow men. To the accompaniment of bugle calls, the thunder of horses' hooves and the loftiest of military gallantry a la Kipling, they show how fair England nobly conquered the bloody 'eathen and self-righteously kept the blighters in their place thereafter. Their place being, of course, beneath the British heel.

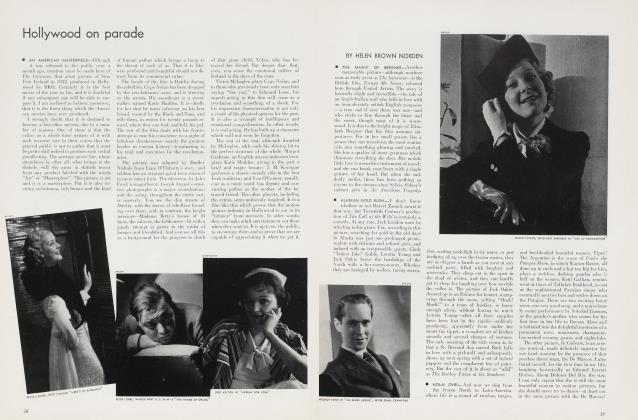

Apart from the matter of social justice, both of the films have their exciting moments. Lives of a Bengal Lancer is by far the better of the two. In fact it's the best film I've seen so far this year, from the point of view of casting, direction and entertainment values. It took four years to make it—during which time it was shelved at least three times—but in the end it was worth it. However mentally disquieting, it is at least emotionally thrilling from beginning to end and contains one episode— the torture scene of the three British soldiers —which you won't forget for some time to come. Franchot Tone does the best work of his screen career—(in fact, it is the first time he has ever shown up as anything but an automaton who could smoke a pipe) — and so do Gary Cooper and Richard Cromwell. They receive excellent support from Sir Guy Standing, C. Aubrey Smith and Douglas Dumbrille. Henry Hathaway was the director, and a superb job he made of it. All in all, Paramount can be well pleased with the layout—as no doubt they are.

THE BRITISH CONQUEROR.—Although directed by Richard Boleslawski, Clive of India was less successful. Perhaps the subject was too big, the span of years too great to cover. Whatever the reason, the picture grows monotonous, and the drama of the original moment in history is never quite recaptured in this celluloid version of it. A. Edward Newton, when he wrote A Magnificent Farce, did a much more convincing job. There are two very exciting shots: the famed Black Hole of Calcutta and the battle scene with armored elephants. The rest of it sort of palls—with Clive in India and out of it and back in again, off again on again Finnigan-like. The big news of the film, for the fans, seemed to be that Ronald Colman had shaved off his moustache, but I just couldn't seem to care.

A NOBLE KIDNAPER.—London Films Productions, Ltd. have turned out a handsome feature in The Scarlet Pimpernel, which is released here through United Artists. The picture was directed by Harold Young and produced by Alexander Korda, and once again proves the skill and imagination of the latter, who was a frost in Hollywood but has been showing us cards and spades ever since he started working with the films in England.

The story itself—that of the mysterious British nobleman who kidnaps French aristocrats on their way to the guillotine and bustles them off to England and safety —is sure-fire adventure and romance. I've never liked Leslie Howard so much as I did in this role, as "that damned elusive Pimpernel." For once, his work is illumined by some gusto and humor, and his scenes when he is pretending to be the foppish and effeminate Sir Percy, swishing around and exclaiming "Sink me! this is all too boring!" are really masterpieces. The slanteyed Merle Oberon, who really merits that much-bandied adjective, "exotic", is cast as his wife, while Raymond Massey turns in a sterling performance as Chauvelin, the Frenchman who was called "The Butcher." There are some particularly interesting atmosphere shots, including the guillotine scenes—with the audience of French housewives who cease their knitting for the brief moment when each new head rolls into the basket—and the scenes in prison where the doomed French aristocrats await their call to death with beautiful and insolent disdain.

MR. ARLISS AGAIN.— The Gaumont British production of The Iron Duke will scarcely add much to George Arliss' stature as an actor, but the film is pleasantly entertaining, and there is the customary letterperfect Arliss performance, even if he isn't quite the Wellington that history records. It is nice to see him bamboozle the crowned heads of Europe, with his customary suavity; and there is one utterly disarming and unexpected shot of him down on all fours, with a bearskin rug over his head, creeping lickety-split across the floor and uttering a fearful "Grrrh!" every odd-second, for the amusement of the Duchess of Richmond's two children. It is almost worth the price of admission to watch the venerable Mr. Arliss cut such capers. No one else in the cast matters.

(Continued on following page)

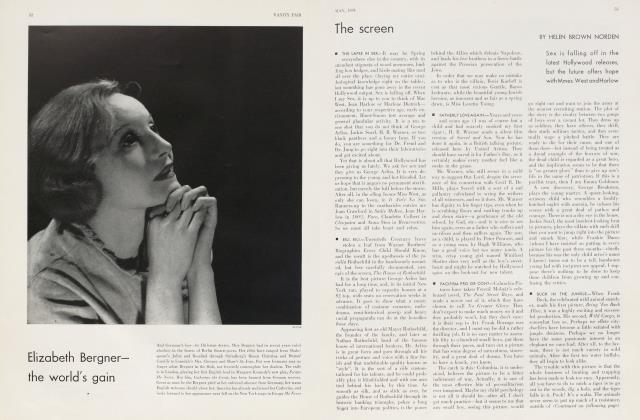

A QUESTIONABLE LILY.— They certainly pick some hot ones for Claudette Colbert these days. A few months ago, they had her in that fantastic specimen, Imitation of Life—an ordinary, routine little Hollywood Cinderella story, in the midst of which was suddenly injected a grim and startling treatment of the race problem, to the great confusion of the movie audiences who were used to having their color on the screen presented in the guise of low comedy, a la Stepin Fetchit, and who were completely mystified when they discovered that this was tragedy and they were not supposed to laugh.

This time, the picture is The Gilded Lily, and, from an ethical point of view, its attitude couldn't be more ludicrous. An impoverished young Manhattan stenographer picks up a young man in the subway, and they fall in love. After a gay whirl for a couple of weeks, he goes away, telling her that he has found a job in the South, but that he will return and marry her. From the next day's newspaper, she finds that he is really the son of a British Earl and that he has returned to England. It is here that the fun begins. Although she is represented as a member of the impoverished gentility —in other words, a "nice" girl—she allows herself to be headlined in every newspaper as "the 'No' girl—the girl who turned down a British Lord." After a vast amount of the most vulgar type of publicity, she cashes in on it by appearing as a freak attraction in cabarets. As the publicity grows, her notoriety increases—and My God, how the money rolls in. Eventually, she goes to London, to be exhibited in nightclubs there. When she meets her Lord again, she is righteously indignant because he no longer wants to marry her but, instead, asks her to spend a week end in the country with him. Her wrath at the "insult" is one of the most ridiculous episodes on the current screen, but unfortunately, it is not meant to be funny. The audience is expected to sympathize with her as an honest working-girl who has been scurrilously treated by a cad of a nobleman. It never seems to have occurred to the authors or the director that her extraordinarily cheap and vicious conduct would have quite justified the Briton in having her summarily clapped in the nearest hoosegow.

There are two leading-men in the film, both comparative newcomers to the screen, who show promise. One is Fred MacMurray, who last year appeared in the Broadway musical, Roberta; the other, who plays the unfortunate nobleman, is an unusually handsome young man, Ray Milland, once a gentleman rider in England, later a more or less unknown performer on the British stage and screen. It seems to me that he is deserving of better treatment at the hands of Hollywood. He has been playing "bit" roles for some time now, and this is his first break.

LESSER NUMBERS.—When I first saw Ann Harding some years ago, in Paris Bound, I thought she was a fine, intelligent actress and definitely top-notch. Since that time, with each succeeding picture of hers, I have liked her a little less. And I have seen a lot of her pictures. The new one, Enchanted April, is about the last straw. It is taken from the novel by "Elizabeth" and tells the story of two neglected and downtrodden wives who rent an Italian villa and thereby are born again and given a new grip on things. Miss Harding and Katharine Alexander are the wives, and I must say, my sympathy was all with their husbands, for surely there were never two more exasperatingly pathetic females. Miss Harding, in particular, is as gallant as they come. Her eyes shine and her voice throbs with tremulous emotion, and she is brimming over with character. All I dare trust myself to say about her is that nothing could fill me with greater glee than to see her one day cast in a film opposite James Cagney—and then turn him loose to do his stuff.

It seems an unfortunate fact that as British straight dramatic films increase in excellence, their musicals get steadily worse. The newest of the last-named is My Heart Is Calling—but it got no answer from me. It stars Jan Kiepura, the Polish singer, publicized here as something pretty fancy in the sex appeal line. As far as I'm concerned, Mr. Kiepura will never break any feminine hearts on this side of the ocean. A plumpish person, given to rolling his eyes and flashing his teeth in a most startling fashion, he is cast as the prize songbird of a traveling operetta company, who becomes involved with a lady stowaway. The picture was previewed at a performance for the benefit of the National Plant, Flower and Fruit Guild. I would rather have had a potted begonia and some nasturtium slips instead.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now