Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSPIRIT AND SUBSTANCE

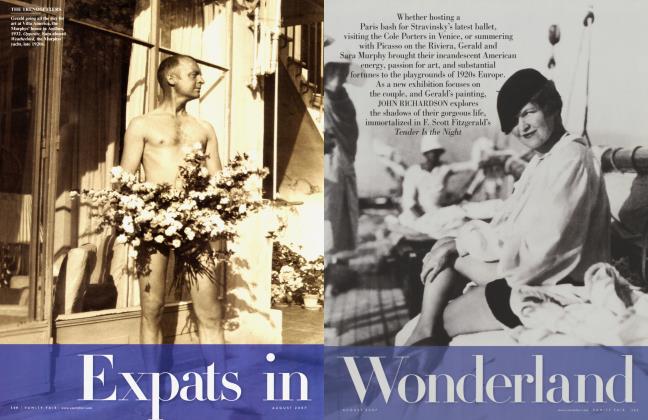

MURIEL SPARK studies a Yuletide fresco by Piero della Francesca

It is always good to see a painting in the very surroundings in which it was conceived and made. Frescoes have a greater chance of resting in their original home than other forms of pictorial art, and this is especially fortunate in the case of the fifteenth-century Tuscan artist Piero della Francesca. His mural sequence, La Leggenda della Vera Croce (“The Legend of the True Cross”), for instance, is in perpetual harmony with the interior of the Church of Saint Francis, in Arezzo, whose walls it enlivens. His Madonna del Parto (“Madonna of Childbirth”), although it has been shifted, remains in its native pastoral and fertile environment at the spot where Piero painted it, sometime after 1450, on the wall of a church later demolished. The fresco is the only adornment of a tiny cemetery chapel which replaced the church, situated below the quiet Tuscan hill town of Monterchi. The chapel is easily accessible from the road between Arezzo and Sansepolcro, birthplace of Piero della Francesca and repository of many of his richest works.

To confront the Madonna del Parto in the small stark chapel is awe-inspiring, even slightly ominous. Something immense is about to happen. Before great beauty and meaning one can only stand aghast. (When the painter Chagall went to see the fresco, he felt fear.)

Piero’s mother came from Monterchi, which is probably why, at the height of his maturity, he accepted the commission to depict the Madonna in so quiet and unimportant a place. Everything about this painting is dramatic. The Madonna is in the last stages of her pregnancy. The Nativity is imminent.

Piero della Francesca was a humanist with a deep sense of the sublime. His Madonna is a substantial country woman and at the same time a majestic, archetypal figure. In no way is she the sort of Italian girl whom anyone might want to help with her problem: this lady has no problem, she has a purpose. She stands in an ermine-lined tent, a tabernacle. She is larger than the angels who, like theater functionaries, draw back the curtains for the audience, the entire human race, to witness Mary’s marvelous condition at this hour. She is wearing a practical maternity dress, which unlaces at the side and in the front to accommodate her splendid bigness with child. Her right hand loosens the lacing of her dress, her left hand rests on her hip, palm upward, in a peasantlike gesture of pride, almost defiance. She wears a halo of burnished gold which mysteriously mirrors the pavement of the original church, but not her own head, so that she, like the angels, seems to be transparent in the light of eternity. She bears this halo with the dignity of a local woman of Tuscany balancing a basket of fruit on her head. The curtains of the womblike tent part to reveal her—as if, about to deliver her child, she is herself about to be delivered from a vaster, cosmic womb.

It is a Christian devotional picture, that of the first Christmas Eve. But the Madonna del Parto, with her radiant and aloof regard, her eyes focused somewhere beyond the ages, seems equally to belong to the ancient reaches of mythology and to our human destiny.

In Piero’s time there was great theological controversy. The Renaissance questioned everything. What was the nature of the Virgin? Was she just an ordinary woman or was she of the divine essence? Questions about spirit and substance were argued endlessly. What is spirit? What is substance? Today we know more about substance than ever before, but the more we know the more it is recognized that we know nothing. Five hundred years have taught us nothing new about the life of the spirit. Piero della Francesca, like all great artists, did not accept any dichotomy between spirit and matter. There is no spirit without substance; the whole of nature is impregnated with spiritual life. His Madonna del Parto, one of the few pregnant Madonnas, is both human and touched with divine revelation. It is a work that reposes in its own mystery: Life emerging into the life of the world, Light into its light.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now