Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVIDEOS TUNES IN

With her subversive, funny videos, Carole Ann Klonarides turns television into art, and vice versa

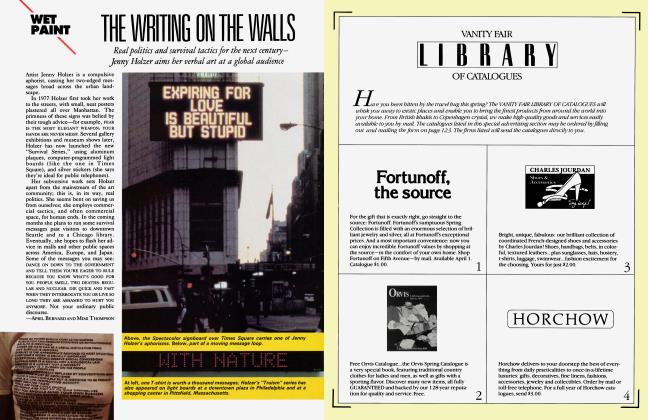

WET PAINT

Carole Ann Klonarides may be the first video artist who’s not afraid of television. Videos have been around for almost two decades now, but hers are something new.

In the past, video art was a much artier affair. William Wegman’s tapes from the early ’70s were like animated versions of his photographs, their deadpan comic success dependent largely on the happy accident that his dog, Man Ray, was a brilliant actor. Then there was Lynda Benglis’s “Female Sensibility” (1974), for which she and another woman solemnly acted out pseudo-lesbo display behavior while country-music lyrics asserted cliches of heterosexuality. A lot of this video seemed to be about artists using themselves as subjects— painfully self-conscious “stars.” Other ’70s artists began working with computer-generated graphics for a vintage Expo ’67 effect, though this could scarcely be called art. The work of pioneer video master Nam June Paik was, of course, in another class; he typically used video as one element in larger sculptures and installations, and few have followed him with success or intelligence.

Carole Ann Klonarides makes her videos with independent producer Michael Owen. Klonarides, a gallery director with a long black braid and training in satellite communications, is an innovator, able to persuade artists, businessmen, and scientists to participate in her projects. She is one of a new breed that embraces the technology of television, most crucially the moving camera eye, which was anathema to artists of the ’70s. Unlike many of her contemporaries, however, Klonarides knows how to make TV work to her advantage.

Some new video makers, like Mitchell Kriegman, have a TV-sitcom approach, which though funny never manages to break away from the sitcom style it uses. Or there’s the visual equivalent of “beautiful music,” which can be seen in the work of Mary Lucier or Kit Fitzgerald. Lucier’s “Ohio at Giverny,” which received so much attention at the Whitney Biennial last spring (and was purchased by the museum for its permanent collection), resembles nothing so much as a PBS special—a self-important homage to Monet (and to Lucier herself), with gorgeous nature photography that relies for its effect on the viewer’s passive snobbery.

Klonarides takes a more sophisticated approach. In keeping with the attention span of the times, her videos are short, about the length of an MTV spot. The earliest ones were made with artists Cindy Sherman (in a “girl talk” interview) and Richard Prince (playing a boring “art bar” conversationalist). In a newer tape, Laurie Simmons is Filmed underwater taking pictures of swimmers, while in a voice-over she discusses art and mermaids. In another, the sculptures of R. M. Fischer (which currently take the form of lamps) are “advertised” with Star Wars visual effects and a professional announcer who urges you to buy “the lamp of the future” today.

Klonarides uses state-of-the-art video equipment but avoids technological overkill. Nor does she subject us to interminable slipshod philosophical enterprises. She manages to entertain us by taking her subjects (but never herself) seriously, and the collaborations are unusually effective. Klonarides would like to show her videos on commercial television. She says, in effect, TV is TV, nothing more or less. In a world where Fine art and commercial art have grown so close, this artist successfully uses (and subverts) both.

APRIL BERNARD

MIMI THOMPSON

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now