Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowART

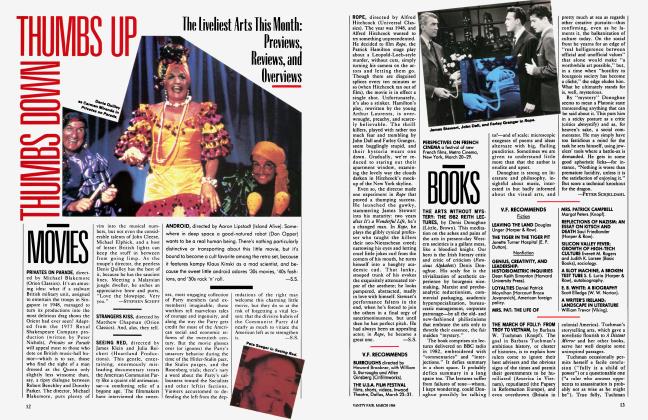

THE VATICAN COLLECTIONS: THE PAPACY AND (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through June 12). This show is an event, no question about it—but an art event? It represents prodigies of diplomacy, logistics, publicity, and sheer expense. What it does not represent, with few exceptions among the 237 items displayed, is the peak creativity of any period covered by the Vatican’s holdings. There are high points— notably Caravaggio’s jokingly fresh, intense Deposition and the mighty Belvedere Torso, a mutilated Greek marble that effortlessly upstages the Apollo Belvedere—but most of the exhibits, from Roman antiquities through medieval reliquaries to African masks, are of a middling interest by major-museum standards, a fact acutely at odds with the heroic presentation. It’s all rather like Hannibal crossing the Alps to deliver a bag of groceries.

Even if all the work were first-class, there would be a bone to pick with the show’s organization as a kind of illustrated history of Vatican collecting. The result is bookish, actuarial coherence at the price of a chronological chaos in which, for example, Renaissance Italy precedes ancient Egypt. Did the organizers assume that we would be fascinated by the vagaries of papal acquisitiveness? More likely, they decided that when it comes to extravaganzas, the medium is the message, and they may be right. The techniques of the supershow—the triumph of fanfare over fare—are so refined by now that they could probably generate hysterical excitement for a roundup of recent kitchen utensils.

PETER SCHJELDAHL

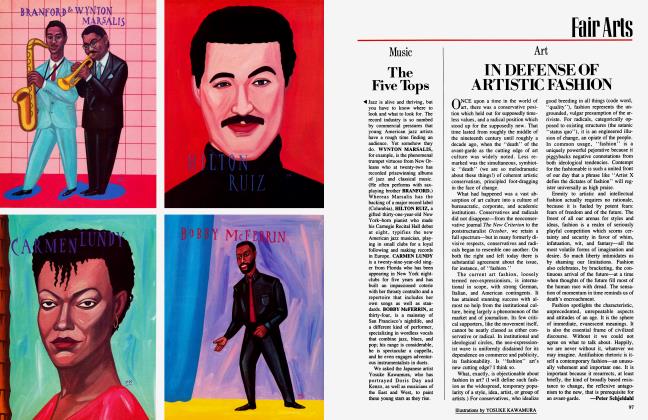

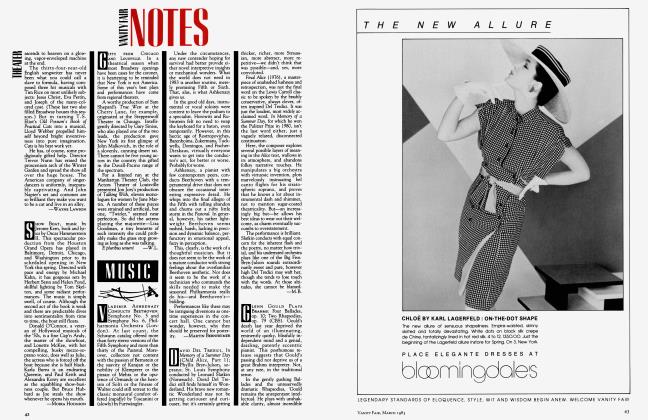

ROBERT LONGO. One of today’s hot young figurative artists, Robert Longo has achieved recognition with his big drawings of chic men and women in violent, ambiguous postures (dance? sudden death?), which are sometimes accompanied by shiny relief sculptures of oppressive architecture. Wide reproduction has made these images virtual logos for the new art generally. So it is auspicious that Longo’s new work, unveiled recently at Metro Pictures and the Castelli Gallery on Greene Street, departs from formula in several directions—some more auspicious than others.

Longo’s poetry of apocalyptic decadence is strong in such new works as Pressure, in which a silvery architectural relief beetles over a drawing of a young man in clown makeup who could be resting between takes on the set of Visconti’s The Damned, and in an astonishing bronze-plated relief (derived from an innocuous magazine ad) of a family huddled together in sleep, a tableau redolent variously of Oskar Kokoschka, Balthus, and Night of the Living Dead. Also impressive is the horribly funny Corporate Wars: Walls of Influence, a relief of eighteen brawling junior executives.

Other new works, including a crude relief of wrecked cars flanked by drawings of children, misfire badly. But a young artist breaking out of his self-imposed lockstep may be forgiven some stumbles, honest awkwardness being far preferable to the coyness that until now has marred an intriguing talent. —P.S.

CLOTHES AS ART. The Denver Museum’s “Shoes and Chapeaux” (through August 7) mixes a lot more than French and English; it’s a rather tony, fetishistic jumble, mostly from Denver society of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This is the kind of show that makes you wonder how museum costume departments got started, anyway. I suppose they’re just part of an inevitable category confusion these days, when anything unique—or in limited supply, like expensive clothes, furniture, and food—acquires the cachet of art.

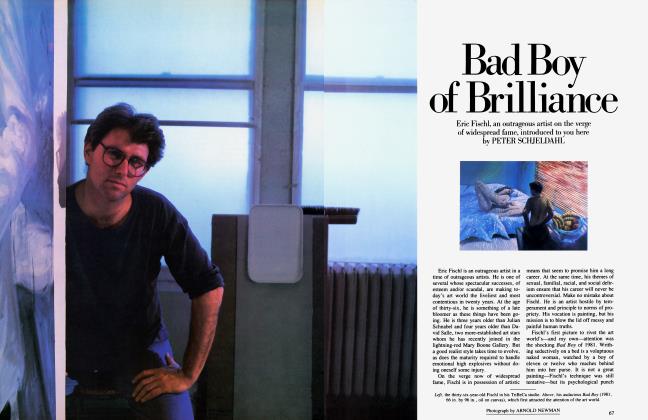

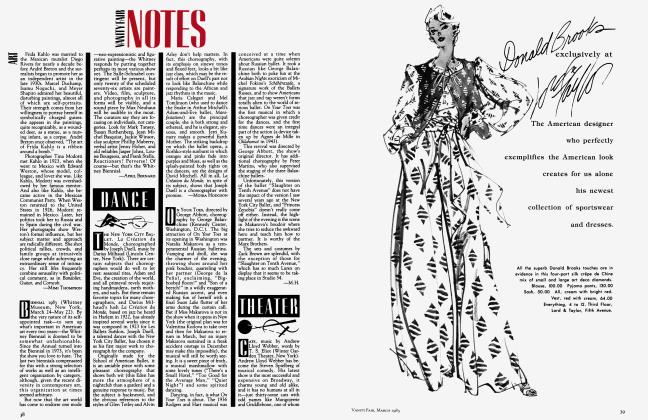

“An Elegant Art: Fashion and Fantasy in the Eighteenth Century” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (through June 2) could have got its inspiration from any one of the periodcostume exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or from the extraordinary “House of Worth” exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York (through September 5). The opulence, the posture, the worldliness, and, indeed, the art of Worth are shocking; these clothes were worn by women who were not innocent for more than about five minutes in their lives.

Charles Worth, established by Empress Eugenie as the undisputed arbiter of the Paris mode, was the only real fashion authority for rich women on both sides of the Atlantic in the second half of the nineteenth century, and these clothes make it clear why. An 1865 swansdown-and-satin ball gown is shown in a decollete modification of its first guise, as a wedding dress (and a more wicked white has not been worn since). Also on display: a rich, deep purple drape of a ball gown; an afternoon dress in ivory brocade with tiny embroidered rosebuds; a little number in screaming red silk caught up at the hip; a regal opera cloak edged with cascades of chiffon. Finishing touches include fur trim, metallic thread, dripping baubles, lace all over the place, and all those attitude accessories—opera glasses, parasols, fans. Best are the fancy-dress costumes: a replica of the dress in Velazquez’s Infanta portrait; a fantasy called “Electric Light,” worn by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt to the Vanderbilt ball in 1883, which looks like a tinsel-and-gold figure of Liberty off a French clock. Visiting, walking, dining, skating, dancing— every occasion had its appropriate outfit. The elaborate calculation involved makes the clothes worn today look like Eve’s before the fall. It took modernism to bring us to innocence again.

Judith Shea’s first clothing-inspired creations, exhibited in the late 1970s, were delicate pattern pieces and dresslike objects that hung on the wall. Light played through layers of fabric that had an Oriental grace, like origami paper before it’s folded. Her new work (Willard Gallery, New York, through May 21) has taken a strong and strange departure: now the forms of cloth are cast in bronze through the lost-wax process. Lay Low, for example, is a piece of a bronze bodice with a detachable bronze sleeve; it comes up out of the floor, as if the rest of the garment were buried beneath. The sculpture simultaneously evokes the solidity of armor and the modesty of a dress: the knight and his ladylove fused. Postmodernism can be innocent too.

APRIL BERNARD

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now