Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

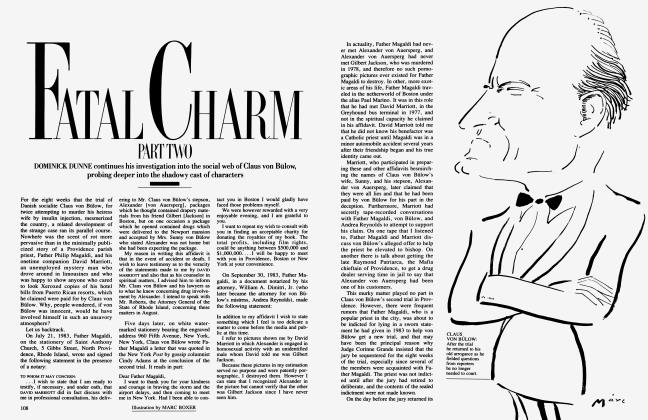

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMarshal Art

The maverick art cop goes it alone

BETWEEN dealers and stealers, art is the world's most illicitly trafficked commodity after drugs. Only about a third of stolen artworks have ever been photographed; $2 million worth used to disappear from New York City every month; Scotland Yard's and Interpol's art-tracking computers are incompatible; and the recovery rate is under 15 percent.

Art isn't even safe behind the Iron Curtain. Near dawn on November 6, 1983, thieves scaled a stone wall around Budapest's Museum of Fine Arts, climbed a scaffold to the third floor, and stole Raphael ' s Ester hazy Madonna (valued at $20 million), his Portrait of a Young Man ($10 million), and five other paintings worth $1 million each—the worst theft in Hungarian history. They left behind a glass cutter and a screwdriver stamped "Made in the U. S. A. " The story of the recovery has never been told before.

The perplexed Hungarians quickly called in the art world's Maverick: Bob Volpe, fortytwo, America's first art cop— and a little bit of every screen lawman you ever loved.

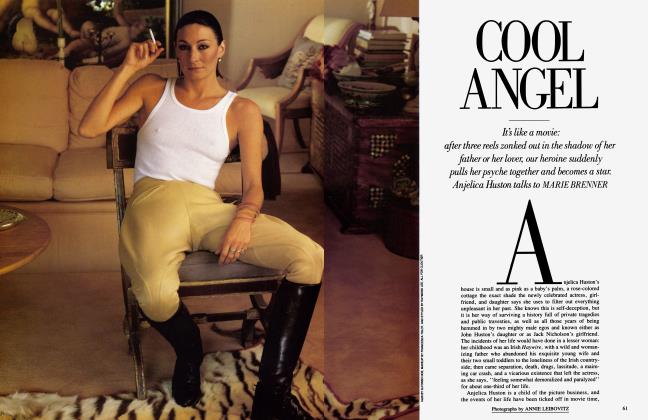

Volpe's persona crosses painterly bombast with hoodlum street-smarts. His shootfrom-the-hip morality is couched in a loner's style. He dresses in jeans and black leather, and his Dirty Harry attitude offended his N.Y.P.D. superiors. The art world loves him, however. "He definitely presents an out-there image," says Donna Carlson of the Art Dealers Association of America. "But I don't care how flamboyant he is. He gets results." Today, Volpe is a private art-crime consultant. With his associate, an ex-tennis pro, he lives a life right out of I Spy, playing his shadowy role to the hilt. He confides that he's even stolen art back from robbers and left them with an I.O.U. "Call it reverse acquisition, ' ' he smirks.

Growing up in Brooklyn, Volpe built a hard-boiled shell around a sensitive nature. He painted his bedroom black and decorated his leather jacket with such finesse that neighborhood street gangs, who'd normally whomp an artistic loner, let him alone in exchange for his painting gang "colors" on their clothes. "That way," he recalls, "they wouldn't break your hands."

Following school, Volpe enlisted in the infantry. Dropped in the woods during war games, his unit was supposed to cross "enemy territory" together. Volpe went solo, inventing the modus operandi he uses to this day: "No one looks for a lone guy without a rule book." He got through, but discovered his troop had been captured, and went back to break them out. Caught in the attempt, Volpe refused to sign a confession, did sit-ups when his captors hung him upside down, sang when they locked him in a box, and broke free when he was stripped, soaked, tied to a chair, and tortured with electrical wires. It was his Great Escape.

Gassed out of hiding in the woods a few days later, he got a call from the police. They'd heard of his escapade and said they could use men like him. He went undercover, a la Serpico, growing long hair and a Zapata mustache. When his painting talent caused his name to pop up on a police computer, Volpe was asked to join a new art-recovery team. Then "his department support vanished," says Donna Carlson. So Volpe arrested a prominent attorney for a series of thefts and called an unauthorized press conference to announce his feat. Grudgingly, the powers that be reinstated their one-man Art Squad. Somewhere, Clint Eastwood smiled.

The Budapest caper was the last of Volpe's many milliondollar recoveries as a public servant. The State Department gave him the standard Mission: Impossible warning: Screw up and you're on your own. So he left for Budapest, but disembarked in London to set up an escape route and an information channel. Only then did Marshal Art saunter through the Iron Curtain.

Volpe suspected Italians had committed the crime. "There was a certain daring to it," he explains. He was sure the job had been commissioned, else "why would they come behind the Iron Curtain?" Only a rich collector could pay for such an adventure; art theft is much simpler in a free society. Since the thieves must have known the scaffold would be there to climb and the primitive alarm system had been broken for a w'eek, he deduced that Hungarians had also been involved. A safe escape route, the Danube, ran through Budapest. A riverbank search turned up a plastic customs bag coded with the colors of the Italian flag. The carabinieri were quickly called into help.

Three Italians and three Hungarians were soon arrested. Raphael's Young Man was found buried in the Hungarian countryside. Gossip from Volpe's London grapevine focused attention on a Greek olive-oil merchant. An anonymous call led Athens police to an empty lot where the remaining paintings had been abandoned. There the investigation stalled; the alleged Greek mastermind stays free, proclaiming his innocence.

Back in New York, Volpe waited for an attaboy that never came. "Recover two stolen cars and you get a medal," he sighs. "This? Nothing. I sensed it was time. I left." On New Year's Eve, Volpe turned in his shield. Marshal Art was alone on the streets again.

Michael Gross

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now