Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowVintage Point

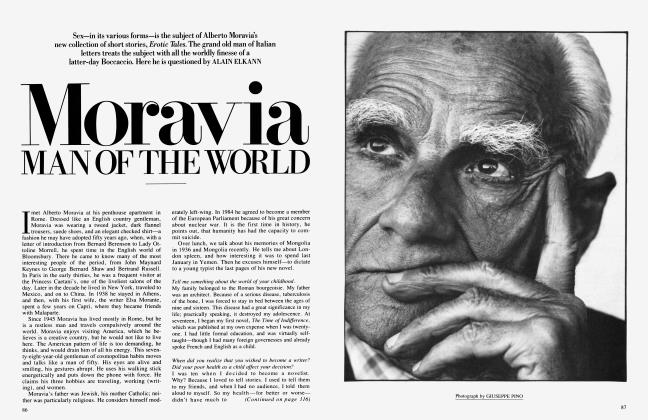

JOEL L. FLEISHMAN

Cabernet vs. Bordeaux

One's opinions about wine depend on what one likes, and what one likes is greatly affected by when one drinks it. Most Americans drink wine soon after they buy it. Since well-made red wine will taste different, and usually much richer, seven to ten years after the vintage date, American wine-makers have a dilemma. Should they vinify their wines so that they will grow beautifully ripe in ten years, or should they make pleasant, immediately appealing wines like those which cartoonists love to poke fun at as "unpretentious and charming but not serious"?

Aging is part of the question of taste, and taste in wine is largely a question of style. A wine can be dry or sweet, fruity or not, huge or tiny, simple or complex, acidic or flabby, tannic or soft, rough or smooth. It can possess varying degrees of citrus, berry, mint, grass, flower, herb, vegetable, and wood flavors. How one feels about these elements of a wine's style will determine whether one adores it or finds it offensive.

Style preferences are dramatically apparent if one compares Bordeaux reds with California Cabernet Sauvignons. The Bordeaux ideal is classicism—finesse, elegance, delicacy, a balance of fruits, acids, and tannins. The California tradition in reds, on the other hand, has been an unrestrained richness, boldness, and fruit power that frequently can dominate the wine flavor in an idiosyncratic way. It is just the opposite of the French ideal. These differences are not simply a consequence of national whims. They are the result of differences in soil and climate, mainly the latter. Simply put, the sun shines much less intensely in Bordeaux than in California, indeed so much less so that in only four of the last twenty-four vintages have most Bordeaux grapes been able to develop sufficient sugar on their own to ferment into desirable levels of alcohol. It is sunshine, along with the heat produced by it, that concentrates in the grapes the fruit flavors with which the soil endows the vine.

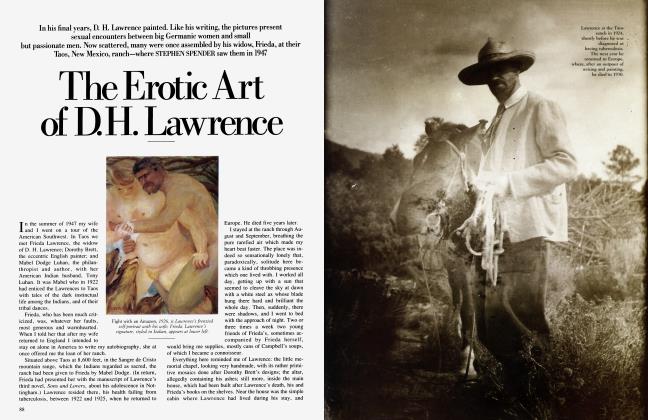

But the style of a wine can be altered by varying the traditional ways of grape growing and fermenting, and in the 1970s California wine-makers, responding to consumer demand, began to shift to a style more similar to that of Bordeaux. (The bulk of California wines, especially at the lower end of the price spectrum, still reflect the older heritage.) Warren Winiarski of Stag's Leap Wine Cellars and Joseph Heitz with his Martha's Vineyard and Bella Oaks have most consistently approximated the balance of Bordeaux, although even those master vintners don't always succeed. It is hard to make a classical wine out of a romantic grape.

Because their robust grapes produce a wine with assertive flavors, California wine-makers have a wide range of possible styles. Jordan Vineyard and Winery in Sonoma County and Mayacamas Vineyards in Napa, for instance, produce Cabernets at opposite ends of the style scale. Bob and Nonie Travers of Mayacamas, who live with their three young sons on the rim of an old volcano in the two-thousandfoot-high Mayacamas Mountains on the west side of the Napa Valley, bought their vineyard in 1968, and from its first release in 1972 their wine has been reckoned among the aristocrats of Cabernet Sauvignon. Mayacamas is always a craggy wine of intense black-currant flavor redolent of cedar and mint which when young can taste overpowering and even medicinal to some. Give it ten years' time or more, however, and it ripens into a breathtaking wine—big, intense, mouth-filling, yet perfectly balanced.

The Cabernet produced by Tom and Sally Jordan at the exquisite Bordeauxstyle winery and chateau they constructed in the Alexander Valley is quite different. From the beginning of its life it is soft and fragrant as well as beautifully balanced, with the gentlest of Cabernet fruit and no obtrusive tannins. The Jordans say that they try to create an early-maturing, easily accessible wine, and indeed that is precisely what they have accomplished. Their Cabernet is now one of the most popular wines in better restaurants all over the country. Unlike the Mayacamas, it is made for pleasant drinking when young. The Jordans are now urging those who own their 1976 to drink it up well before the 1976 Mayacamas has reached its prime. Both of these wines are Californian, both are Cabernets, and yet each is as different from the other as the quintessential Bordeaux is from the stereotypical American product.

Even as the Californians have been striving to make elegant wines from assertive grapes, the Bordelais have been deliberately seeking to make wines less tannic, with more obvious fruit flavors, and more pleasant to drink young. The conventional ideal wine types are therefore increasingly less common. Craftsmanly vinification weighs just as heavily on both sides of the Atlantic.

If you have any doubt about the possibility of finding a delicate California wine, try a 1978 Joseph Phelps Eisele Vineyard, a 1977 Heitz Cellars Bella Oaks (both about $40), or a 1982 Whitehall Lane (about $12). All have powerfully concentrated fruit flavors characteristic of California at its most paradigmatic, and I'll wager you will be moved to describe them as elegant and perfectly balanced, too.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now