Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOut to Lunch with A1 Hirschfeld

The celebrated cartoonist lines up lunch for ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST

Al Hirschfeld feels he gets far too much respect. "You can't offend people anymore,'' he said. "It's almost impossible."

An example: the caricature of mercurial producer David Merrick that Hirschfeld executed for his main venue, the Sunday New York Times. "I drew him with a snaggletooth," Hirschfeld says. "And kind of slavering. He loved it. He bought it, and used it as his Christmas card..."

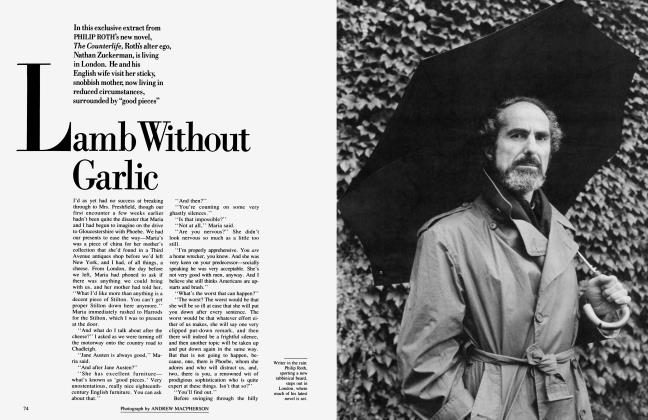

I was lunching with A1 and Dolly Hirschfeld in their commodious Manhattan town house. Hirschfeld was in a purple turtleneck and tapestry carpet slippers. He has a white King Lear beard, dark eyes, and Mephistophelian black eyebrows. Dolly Haas, his actress wife, has delicate features and reddish hair worn a bit like Gidget and a bit like the Empress Eugenie. Both, in fact, look like raw material for Hirschfeld drawings.

"There's something strange about this business of recognition," he observed, spooning up the soup. "It's not just anatomy. You'll recognize a friend a block away. It's a back view, it's snowing, and he's got a new coat, but there's something about him you can identify. How is that? Everybody's got that gift. I suppose my contribution is a visual thing. People recognize what / saw."

A1 Hirschfeld is eighty-three, a matter of small consequence for a working artist, but it does mean he came of age in a time of exuberant graphic invention, the cartoon side of Art Deco. In 1924 Missouri-born Hirschfeld went, obligatorily, from New York to Paris. "I was a sculptor," he said as Dolly doled out the omelet, adding, "A sculpture is just a drawing you fall over in the dark." Drawing was the thing. He returned to a studio in Greenwich Village.

Wine was poured into floral goblets, a present from Gloria Vanderbilt. A memory popped into Al's mind concerning our illustrious precursor at Vanity Fair. "Frank Crowninshield was one of the greatest editors of all time, but he refused to accept the Depression. I remember a meeting. Gropper"—a fine artist—"said, 'Look, Crowny, I would like to do a triptych of the outhouses on the Lower East Side.' Crowny almost threw up. He said, 'What do you mean?' Gropper said,

'You don't realize. All those big buildings on Second Avenue don't have toilets. They have outhouses in the backyard.' Crowny said, 'I don't believe a word of this.'

"In the same meeting, he went through a magazine and picked out an ad for silk stockings. It went, 'Guaranteed not to see you through the evening.' He said, 'Now, that's the kind of advertising we should aim for.' This was at the height of the Depression."

Hirschfeld survived on his drawings. "There's so much you can do with shading, and anatomy," he said, "but there's a kind of gaiety to a line. A magic. Like an early Disney thing." Another memory popped up. The Times had asked Hirschfeld to draw his idols. He drew Chaplin, and Fred Allen, and wanted to do Walt Disney. "I went out to Hollywood, and met the great man," he said. Afterward, though, a couple of Disney's animators grabbed him and hauled him off to a meeting. "They said, 'Walt has great executive ability. But he has no idea what drawing is all about.' I said, 'C'mon! What about Mickey Mouse?' They said, 'Have you ever seen Walt's original Mickey Mouse drawing?' They showed it to me. It's a mouse! It's a rat! With little claws, a long tail, and a snout."

Over the cheese, we approached technique. Hirschfeld, to my sur| prise, doesn't always use photo2 graphs of his subjects. He often works directly from the screen when doing movies or TV, live in the theater. "Across the years I've learned to draw in my pocket," he said. "Then I come back, and try to translate them." Does he ever distract his fellow theatergoers? " he said, firmly. "No." "Oh, darling," said Dolly. To me: "He gets so absorbed. Sometimes they hear the scratching of the pencil."

Hirschfeld looked quite startled. "I had no idea," he said.

They never mind, she reassured him. Certainly, Hirschfeld himself bulks as big to many of them as the performers he skewers or caresses with his nib. "He gets the autograph hounds," she said. "All it takes is to stay alive," Hirschfeld observed, mildly. "I get a lot of fan mail. Mostly from prisons."

Is there much gone that he regrets? More than the once dreaded power of the caricaturist—"David Low was the last to have that"—what he misses is the way artists and writers in Manhattan used to share experience. "We would meet every Thursday," he said. "Charlie Addams, Brooks Atkinson. We had a lot of fun. That camaraderie has dissipated somehow. We tend to romanticize these things, but it all has to do with economics. I know what lofts cost. Everybody has to pay the rent."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now