Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

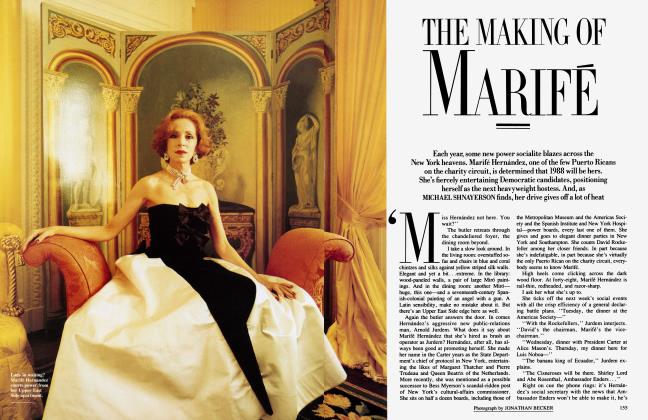

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFox hunting has never been more popular—or unpopular—than it is now in Mrs. Thatcher's Britain. The violent passions that clash around this age-old blood sport are focused on the dashing eleventh Duke of Beaufort. CAROLINE BLACKWOOD reports on the Duke, the dangers, and the royal connection

December 1987 Caroline BlackwoodFox hunting has never been more popular—or unpopular—than it is now in Mrs. Thatcher's Britain. The violent passions that clash around this age-old blood sport are focused on the dashing eleventh Duke of Beaufort. CAROLINE BLACKWOOD reports on the Duke, the dangers, and the royal connection

December 1987 Caroline BlackwoodAt first sight, this meet of the Beaufort Hunt looks as traditionally merry as a scene from an English Christmas card: a party on horseback before the day's equestrian exertions. The local villagers bring their children to gape at the beautifully groomed horses, the stirrup cups of port, sherry, or cherry brandy, and the exquisite hunting clothes. The women wear hairnets, to avoid entanglements with low-hanging branches, and stocks, long white cravats fastened with a gold pin, which can be used as bandages or tourniquets in the event of an accident. The men sport "blue and buff' coats (not the usual scarlet always called "pink" after a legendary eighteenth-century London tailor named Mr. Pink, who perfected the cut) for no good reason that has been discovered except that the Beauforts simply want to be different.

Different they certainly are. They are perhaps the grandest of the English hunts, not simply because Prince Charles regularly "goes out" with them, but because their master of foxhounds is the eleventh Duke of Beaufort himself. No title is more powerful in fox hunting, more revered, and more reviled. The intense feelings the name invokes go right back to 1066: William the Conqueror made it a snob sport by allowing only his French-speaking Normans to hunt. Since then it has had connotations of nobility, a peacetime rehearsal of the knightly skills of war. The hunting field has also always been a major battlefield in Britain's periodic class warfare. The Beauforts—a French name, naturally—are directly descended from that fierce implacable stag hunter, John of Gaunt, son of the Plantagenet king Edward III. If there had not been the dark ancient stain of illegitimacy blotting their escutcheon, the Dukes of Beaufort would be the rightful Kings of England. In the seventeenth century, roaming gangs of hungry soldiers from the English Civil War changed hunting forever by slaughtering stags in such vast numbers that they became virtually extinct. The nobility had to switch the focus of its depredations to the comparatively unrewarding hare—until one day in the eighteenth century when the fifth Duke of Beaufort was out with his hounds and they scared up a fox, hitherto considered an ignoble quarry. He decided to let the pack pursue it. and discovered that the fox afforded the huntsman much more pleasure than the hare, which ran in meandering circles. The fox ran straight, giving the riders what they longed for—"a good run." Other noblemen copied him. and when the Prince Regent took up the fashionable sport, the fox became the prey of choice.

The true huntsman is a man of leisure, and this can madden those whose lives are burdened by the necessity of work.

As class feelings have polarized in Mrs. Thatcher's Britain, fox hunting has never been more controversial. More people hunt in 1987 than have ever done in the history of the sport. The upwardly mobile try to arrange for their children to hunt, hoping they will marry the aristocrats they ride beside. On the other hand, fox hunting has never been so unpopular with other segments of the population. The Falklands spirit of the "pro" traditionalists is matched by the increasing intensity of the animal-loving "antis." This apparently archaic and parochial question still remains a political issue, arousing violent British passions, which came to a head in a bizarre and gruesome incident three Christmases ago—aimed directly at the heart of the Beauforts.

Nine young members of a fanatical animal-rights organization with the sinister name of the Hunt Retribution Squad broke into the private Beaufort burial ground at Badminton parish church. They tried to dig the tenth Duke out of his grave, but their spade broke. Five of them were caught, and two were put on trial. They were sent to prison for two years.

The Retributionists admitted they were planning to dig up the Duke's corpse—they wanted to cut off his grinning putrified head in order to send it, gift-wrapped, to Princess Anne, lake her brother Charles, the Princess has always been passionately keen on fox hunting, and both, along with Princess Diana, the Queen, the Queen Mother, Prince and Princess Michael of Kent, and Princess Alexandra, were prominent at the tenth Duke of Beaufort's magnificent funeral.

Henry, the tenth Duke, was the undisputed king of fox hunting. He died at the age of eighty-three, of a third heart attack, after a final day out "following" his hounds in a car. According to local legend, the old Duke had seen three foxes haunting the burial ground at Badminton in the months before his death. Foxes dance on their hind legs when they are happy, and it is said that all three were dancing feverishly, their mouths open in an appearance of grinning jubilance. The three foxes signifying the three coronaries. There was good reason for the foxes to dance for the Duke's death. All his long and happy life that bluff and genial man hunted foxes—often six days a week. (By definition the true huntsman is a man of leisure, and this can madden those whose lives are burdened by the necessity of work.) Sometimes he hunted fox cubs twice in a day, at five in the morning and again in the afternoon, enabling him to boast that he had often hunted nine days a week.

Addressed as "Master" as a boy, he liked the title so much he decided to adopt it forever, much preferring it to the correct ducal one of "Your Grace." Apart from the "antis," who called him "Bloody Beaufort." everyone always called him Master, from Queen Elizabeth to the newspapers that mourned his passing like that of a second Churchill. FAREWELL TO MASTER. . .THANK YOU, MASTER. . .THE NOBLEST MASTER OF THEM ALL, ran some of the headlines. Feminists may shudder, but his wife, Mary Duchess of Beaufort, also called him Master. An admirer who attended his funeral service described the prayers: "We gave thanks for Master's mastership of horse and hound and man." Spoken in 1984, they were astonishing prayers.

Fox hunting is said to be an addiction like alcoholism and drug abuse, and Prince Charles is hooked.

Henry Beaufort died childless, and the present Duke, David, is only a cousin of the last of the great British masters. When he inherited this anachronistic hunting dynasty at age fifty-five, he was an important figure in the Marlborough international fine-arts gallery. Devilishly handsome, sophisticated, and charming, he was considered by many to be one of the most glamorous men in England. Whereas Master loathed going a few miles beyond his own hunting country, David owned a private plane and loved to travel. His wife, Caroline, and their four children lived in a pretty, manageable house in the next village to "the great house" at Badminton. His daughter, Anne, is a writer, currently working on a book about Elizabeth I, and his eldest son, "Bunter," the Marquess of Worcester, after a flirtation with rock 'n' roll, is now interested in property development. In this summer's social wedding of the season, he married Tracy Ward, the beautiful younger sister of actress Rachel Ward.

The immediate problem of David Beaufort's inheritance was Badminton House itself, an intimidating Versailles of a place with a hundred or more rooms, correctly described as having "heroic" proportions. It is also heroically cold. Master, hardy from all that hunting, never felt the cold. One original plan was for the family to continue living in the smaller house and subsidize the enormous upkeep of Badminton by opening it to the public as a museum. But, alas, because the Beaufort ancestors were too fond of fox hunting to spend much time collecting works of art like many other British aristocrats, Badminton contains little to attract visitors. Anne has described her dismay when she first heard that her father was quitting the smaller house to live at Badminton. He has now modernized a fraction of the rooms at his disposal, putting in a new kitchen and forming a normal-size dwelling within the palatial framework of the original.

Having solved his unusual housing problem, David still has other unusual problems. When Master died, David automatically inherited the dual title of king of the British fox-hunt and "Bloody Beaufort." By no means as keen a huntsman as his predecessor—he only hunts about twice a week—he is still the focus of venomous hatred. Hunt saboteurs regularly interrupt meets, screaming, jeering, brandishing banners with accusatory slogans such as SADISTS IN PINK COATS, and deliberately trying to frighten the horses. (The League Against Cruel Sports, rich from bequests by animal-loving old ladies, has started buying up strategic tracts of land and suing hunts for trespass. In an important test case, it was recently awarded £70,000 because hounds were seen running through its acres.) Extremists do alarmingly unpredictable things once the hunt is under way. They have threatened to place trip wires in front of the horses to bring down riders. They are prepared to risk their own lives to save that of a fox. They run in front of the hounds when they are in "full cry," spraying Antimate to smother the scent trail. The riders, caught up in the broiling excitement of the chase, get enraged at this "coitus interruptus." They lash out mercilessly with their horsewhips— many "sabs" have been seriously hurt. Feelings are inflamed on both sides. The master of the Essex Union Foxhounds recently made this amazing statement: "Horsewhipping a hunt saboteur is rather like beating a wife. They are both private matters." Whereas a young member of the Hunt Retribution Squad said to me, "I don't see anything wrong with killing a huntsman." He had frighteningly crazy eyes and I didn't disbelieve him when he went on, "If a huntsman is prepared to kill a fox, I'm prepared to kill him."

Prominent huntsmen therefore put themselves in considerable danger. The otherwise mild Prince Charles is obviously a target. The saboteurs loathe him for setting what they see as a barbaric example when he makes his frequent appearances on the hunting field. For several years he behaved rather surreptitiously—he allowed it to be understood that he had given up the sport because his bride hated its bloody side. But fox hunting is said to be an addiction like alcoholism and drug abuse, and the Prince is hooked. He still tries to keep it a secret, never going to a meet, only joining the riders quietly once the chase is on. Not that you can really pursue the sport in private; with his famous face and his famous ears he is very soon recognized.

The men and women who hunt beside him insist with pride that his life is never in so much mortal danger as when he hunts. Not just the inherent physical dangers of getting thrown, not just his usual enemies such as the I.R.A. (who killed his beloved great-uncle Lord Mountbatten), but also the fanatical activists among the sabs. His security men become impotent, sitting pointlessly in their high-security vans with all their useless high-tech equipment while the Prince flies over the enormous, perilous hedges and ditches that only an experienced initiate can take in his stride. Deprived from birth of that great human luxury, privacy, he loves hunting because it gives him a unique opportunity to lose himself. Chasing after the fox, he can escape the constant presence of his guards and detectives, he can forget about his mother, his wife's mega-star image, and his obligations to the nation. He gets screamed at, he gets cursed, and he loves it. Only in the army or in prison is the language as foul as on the hunting field. "No one treats him as a future king when he's out with the hounds,'' I was told by a committed huntswoman. "That's the only time Prince Charles feels human." She and her kind boast that he has a very good chance of perishing on the field. They would think it a princely end.

David Beaufort is the only other Englishman who places his life in equal danger every time he rides out to master his hounds. They may not have succeeded in digging Master up, but his opponents have not forgotten him, or forgiven him. At a recent Badminton Horse Trials, a key equestrian event, protesters streamed into the ring and waved banners at the Queen that said, DIG DEEPER FOR THE DUKE. That sort of thing can be very wearing. "Poor David has aged in the three years since he inherited the title," says a friend.

He may prefer the art world to the horse world. He may not want to meet a "princely end" at the hands of a be-crazed saboteur. But the aristocratic traditions shift slowly, and bearing the great fox-hunting name of Beaufort, he is obliged to hunt the fox—and put his life in jeopardy.

As his friends say, "Poor David."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now