Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWAITING FOR BANTAM

Bantam's New Fiction line kicks off with a St. Louis waiter and a stewardess

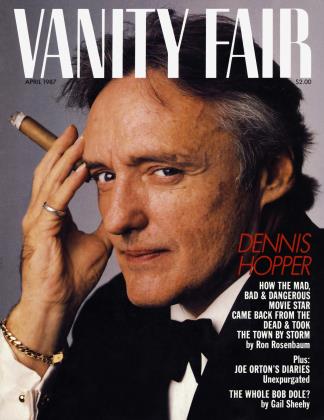

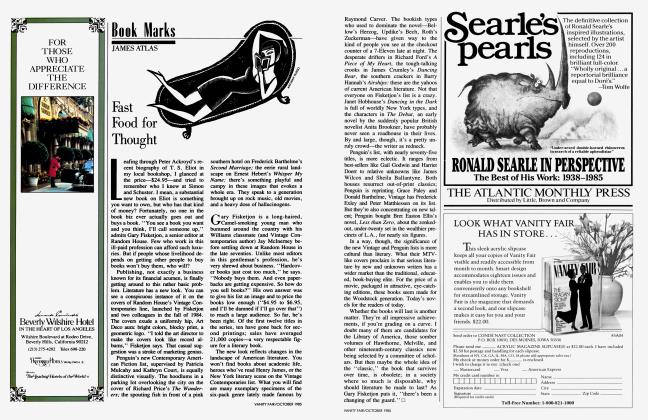

JAMES ATLAS

Book Marks

'Glenn Savan was born in 1953," reads the author's note to White Palace, forthcoming from Bantam's New Fiction line this summer. "He is a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and a former advertising man. He currently waits tables in St. Louis, where he is at work on a second novel." He waited tables. Now that Sydney Pollack—in collaboration with Griffin Dunne and Amy Robinson—has optioned the novel for $30,000, with a $200,000 guarantee if the movie gets made, Savan has hung up his towel. For three years he hustled tables at night at the Webster Grill and Cafe, "a Califomia-esque restaurant with hanging plants" in suburban St. Louis, writing his novel during the day. He heard about the movie sale one afternoon just before he went on duty. After British rights were sold, enough was enough. "I saw all this money rolling in and it got hard to maintain the proper attitude," he says, adding that the management has been "very nice."

Savan himself is very nice, which doesn't surprise me. His novel is, among other things, an act of consider able imaginative sympathy. From the moment we're introduced to Max Baron, a young advertising copywriter who is struggling to recover from the death of his wife in a car accident, he radiates the kind of fundamental decency that has a name in Yiddish; he's a mensch. It's true that he's fond of his good looks, "probably far more vain than men less handsome than himself." And he's guilty of unliberal thoughts, quick to admit his distaste for the white trash of South St. Louis that he sees from his car window on the way to a White Palace hamburger stand, "the barbaric beards and shaggy hair, the Budweiser T-shirts, the cheap rubber sandals from Woolworth's, the glum faces, the general uncleanliness ..." But Max is no spoiled suburban boy. His father was "a faceless peddler" who abandoned the family when Max was a baby; his mother is indigent, crazy, a bag lady with a roof over her head. Max's life hasn't been hard; it hasn't been easy. He's basically a mild young man who's suffered a souldestroying disaster.

Until he falls in love. Pasty, chainsmoking, "not young," Nora is the girl—the woman—of no one's dreams. She works behind the counter at the White Palace ("Shit City"), lives in a crummy neighborhood known as Dogtown, has never read a book in her life that wasn't about Marilyn Monroe. So what does he see in her? She's good in bed, to start with; she has pride—what her neighbors might call spunk—and she isn't dumb, even if she is "like some character out of Tobacco Road or something," as one of Max's cronies describes her. Max may be the one whose advertising spots appear on TV, who listens to Mozart on his tape deck and works his way through the collected Shakespeare, but Nora knows a few things about life—the one subject these nice Jewish boys usually flunk.

What keeps their affair going is passion. White Palace contains some of the hottest sex scenes in a contemporary novel since Scott Spencer's Endless Love. But sex isn't everything. There are still plenty of obstacles. White Palace is a story about love and class— "Pygmalion with a twist," it occurs to Max when he hears himself using one of Nora's expressions. ("As the play progresses, Professor Higgins discovers that he has taken on a cockney accent, and by the end of the last act, he's on a street corner in Soho, selling flowers.") Or Of Human Bondage, Maugham's novel about Philip Carey, the failed artist who falls in love with a waitress. (Savan read it while he was working on his own book.) It isn't until Max learns. . . but read it yourself. And then go see the movie.

The son of an advertising executive— there are terrific scenes about the business in his novel—Savan kicked around in the seventies, and finally got a degree from the University of Iowa. After a stint in the New York advertising world with a now defunct firm ("My big account was Manischewitz wine"), he returned to St. Louis and worked for his father until he got fed up: "I was waking up every morning with clenched teeth." It was less enervating to wait tables while he worked on his novel than to write ad copy. "I didn't know if it was going to be this book or the next book or the next that got published, but I knew it was what I had to do."

The waiter who gets his novel published—it's a wonderful story, but lots of waiters (based on a sampling of employees at the Museum Cafe on Columbus Avenue) are writing novels. Now, Ann Hood, the other novelist making her debut in Bantam's new line . . .Ann is a flight attendant. A stewardess. She studied literature at the University of Rhode Island (class of '78) and was "always a closet writer," she says, "but I didn't have anything to write about. I wanted to meet people, see the world, get some experience." So instead of heading for the nearest M.F.A. program, she got her wings. When she wasn't flying, she was writing. She enrolled in a literature and creative-writing program at N.Y.U., studied with E. L. Doctorow, and spent some time at Bread Loaf, the famous writers' workshop in Vermont. When she had a few short stories under her belt she showed them to George Murphy, the editor of a little magazine called Tendril, who showed them to the literary agent Maxine Groffsky. Groffsky liked them but suggested she come back when she had a novel. A few months later, Hood returned with a partial manuscript in hand, and Groffsky took it to Deb Futter, one of the founding editors of the Bantam line, who bought it. Laid off by TWA in a labor dispute (in other words, ''I got fired"), Hood is flying with Presidential these days, and working on a new novel while she waits for this one to be published. ''I have my sights on hanging up my wings," she confesses.

Her novel, Somewhere off the Coast of Maine, is an estimable debut. It tells the story of three classmates at an unnamed eastern college in the mid-sixties and what becomes of them. Hood's multiple point of view—the narrative is told not only from the vantage of her three heroines but from the vantage of their kids—furnishes a new perspective on that overdocumented era. There are the familiar sixties scenes in flashback— smoking dope, marching on Washington, knocking around the country in someone's van—and Hood does them very well. But it's not her life; bom in 1956, she experienced the sixties as history. Somewhere off the Coast of Maine may well be the first novel to see those of us who came of age in the sixties as we look to our progeny—the children of the flower children.

Poised between two generations, Hood is a shrewd chronicler of both. The parents listen to Dylan; the children listen to the Dead Kennedys. The parents reminisce about how many times they saw The Graduate; the kids worship Spielberg. The children are sophisticated beyond their years; the parents seem oddly vulnerable, undergraduates who mysteriously got old. Now in the neighborhood of forty, they're aging quickly—and brutally. One develops cancer; one has a nervous breakdown; a son drowns; a marriage breaks up. Yet they're still clinging to the sixties dream: Claudia lives on a farm in the Berkshires; Elizabeth is a potter. Only Suzanne, a successful investment counselor, has sold out. In her posh apartment on the Wharf in Boston, she presides over an awkward reunion, fretting about the lobster bisque, boasting about the Pouilly-Fuisse. ''You've entered a totally new dimension," Claudia declares in a Rod Serling voice. ''The 1960's zone! Suzanne thought she was in the seventies, but suddenly strange things began to happen to her. 'Puff the Magic Dragon' played on the piano. Women with long hair showed up on her doorstep. And cheap Chianti appeared in her hand. Without realizing it, Suzanne had stepped into the sixties zone."

Glenn Savan waited tables—until Sydney Pollack optioned his novel for $30,000.

A antam is launching four other titles 1C this year in its New Fiction line, all Iw as paperback originals. Unlike Vintage Contemporaries, the pioneer in this now pervasive marketing strategy, Bantam intends to publish only original works—no reprints. Whether it can keep up the high standard of its inaugural offerings remains to be seen, but it's heartening to see novels by unknown writers published in a handsome, inexpensive format. Despite the bad news about the industry—the cutback on serious books, the excessive concentration on blockbusters, the power of the bookstore chains—some publishers are still willing to put up decent advances (Savan got $20,000 for White Palace) in the hope of a modest return, and to promote the books they publish; a $100,000 launch campaign for Bantam New Fiction is in the works.

So the novel isn't dead. There are people out there determined to write, even if they have to wait tables or serve complimentary soft drinks and cock-1 tails on the Washington-Indianapolis flight to do it. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now