Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSMALL WONDERS

Art

In a world of Big Art, the discreet charm of Edouard Vuillard shines

MARK STEVENS

Edouard Vuillard, now the subject of an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum that focuses on his work from the 1890s, is rich in exactly those ways in L which we are poor. That is partly why his art seems so useful at the moment—and also why he is occasionally overlooked or treated with condescension. Because Vuillard HHI painted small, quiet pictures of women (twelve inches by eighteen inches is fairly large for him), he is sometimes regarded as a nice little master, important but rather dainty, like a jeweler or a maker of fine lace. Good in the bedroom, perhaps, but not over the mantel.

Smaller can be better in an era when big is too big. Persian miniatures, medieval manuscript painting, the work of Paul Klee—such things seem particularly interesting right now, given the potbellied character of the contemporary art world, with its lip-smacking appetites, dumb worship of size, and failure to appreciate the discriminations of scale. An artist like Vuillard brings measure. He understands intimacy. His whispers and intuitions are no less vital than the insights of artists with an imperial imagination, who seem to sit astride the world.

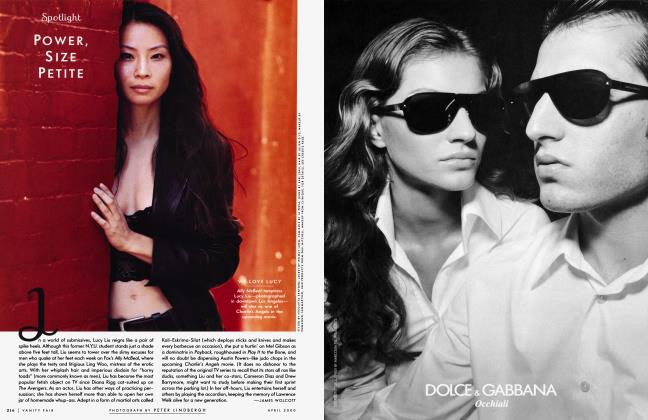

Not surprisingly, much of what Vuillard knew came from the study of women. Bom in 1868 into a modest family, he lived in Paris with his mother, whom he called his muse, until her death in 1928 when he was sixty years old. (His father had died when he was young.) His sister and niece were also an inspiration to him, and the unrequited love of his life was a glamorous Polish pianist named Misia Natanson, who kept a fashionable salon. Visiting this exhibition, which was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, is rather like eavesdropping on women from behind a curtain.

"When my purpose tends to men," Vuillard wrote in his journal, "I always see burdened wretches, I have only the feeling of ridiculous objects. Never [so] in front of women, where I always find a way to isolate a few elements that satisfy the painter in me." Vuillard's mother was a corset-maker who ran her business out of their small apartment, so seamstresses were always around. The apartment itself was a crowded jumble of feminine things: decorative objects, furniture, patterned wallpaper, bolts of cloth.

Attracted to symbolist theory, which emphasized an artist's subjective vision over the rendering of surface appearances, Vuillard began to endow this cramped environment with a powerful but elusive emotional charge. He brought a luminous hush, a velvety reticence, to art. Like Cezanne, he also found a way to give substance to the shimmer of Impressionism, though not through Cezanne's disinterested analysis of form. In Vuillard, people and patterns combine to make something more than themselves; he does not paint things so much as moods. And the mood is always rich, substantial. Vuillard's painting lies thick and creamy on the eye, like chocolates on the tongue.

Although Vuillard flattens his forms, he does not do so uniformly, which typically makes the spacing in his work seem unstable or ambivalent. The use of a thick glue-based paint and an exquisite feeling for the weighting of shape and color help the pictures "hold." One must approach a Vuillard in a certain way. Instead of standing back, one leans forward, pulled into the vortex of the little world. Once inside, it is not easy to stand back. A Vuillard suffuses the eye. Power in art is now generally understood as expansive: the sensibility of the artist flies outward, revealing secrets. Vuillard had a contracting imagination, a closeted heart.

The pictures most fraught with tension are those of his family, often at table. Vuillard did not usually paint faces in detail, but one always recognizes his mother. She looks rooted, as sturdy as a house; one knows immediately that she is a person who sucks up all the oxygen in a room. Vuillard's sister, by contrast, is usually in an awkward pose, as if forced to the side by her mother; in one picture, she is fading into the wallpaper. In all the paintings there is something not quite said or acknowledged, and it sometimes seems sexual in nature. Occasionally a certain line is crossed. In an early self-portrait of Vuillard embracing his sister, the pose is decidedly erotic, although this picture is also full of odd elisions. The lips seem to meet, but there are no lips—the faces are kept safely abstract.

Vuillard's pictures of women are all the more moving when they include two or more figures, solitaries together.

The repression is wonderful, the smallness sublime. The sonorous mufflings, the excitement of what one loves but cannot have, enhance Vuillard's art, however unhappy they may have made the man. Being too precise about what is going on—making too much of underwear and corsets, for example, which Vuillard never actually portrays in his paintings—is beside the point. Our pleasure lies in the steamy power of angers buried in the heart, in the titillations of not quite knowing. Vuillard paints as if to listen, and his ear (rendered red in certain self-portraits) is cocked. If he savors the secretive—whereas we tend to prefer knowing and exposing—he also enjoys the solitary. His pictures of women sewing are celebrations of private absorption. They are all the more moving when they include two or more figures, solitaries together.

Later in the 1890s, a window opened in Vuillard's airless room—his sister was married and gave birth to a girl. Before the charm of this child, Vuillard and his formidable mother let down their guard. The painter's palette lightened and he portrayed the whimsical little creature playing around windows giving onto lovely views. The pictures are surprisingly unsentimental; the child is brilliantly observed, her characteristic gestures seen as if for the first time. Vuillard's passion for the Polish pianist was less happy, but it also helped move the painter away from the suffocations of family. The pictures of Misia tend to be somewhat larger, more luxurious in tone. Since the object of his devotion was a Polish pianist, the paintings also seem musical (Chopin, of course) in their patterning and are steeped in that gorgeous but rather sickly romantic melancholy of the nineteenth century. In one picture, the pianist's husband is placed in a far comer, while Misia herself is served up front and center for ravishing by the painter's eye. She is asleep in a chair—thereby remaining a perfect idol. Misia told in her autobiography of once taking a walk in the woods with Vuillard. When she tripped, the painter caught her, looked into her eyes—and burst into sobs.

In certain ways, the "repressed" Vuillard offers a paradoxical escape from the puritanical spirit, especially from the withering kind of intellectuality and self-consciousness that is always trying to boss art around. The 1890s were, like now, a period much taken with theory, yet Vuillard never let theory become his master, while still remaining a man of his time and a serious student of the new thinking. Nor was he afraid to paint with luscious abandon. Postwar American work has often made a point of resisting, admirably, the tasty pleasures found in French art. But the joys of laying on the paint should not require an apology when presented with formal grace and no vulgar motive. In Matisse, pleasure becomes transcendent, Edenic. Vuillard was too neurotic for the Garden, but his facility is never cheap.

He was also free to celebrate the traditionally feminine. Today, these values are much too fraught with ambivalence for artists to portray them with the loving rapture of a Vuillard. The widespread anger of women over being confined for so long to such values means that serious artists may now show sympathy, respect, and interest, but not real devotion to the dainty, small, fine, delicious, secretive. As a result, a significant aspect of the human imagination, which is not the exclusive preserve of either women or men, fails to find serious expression.

Vuillard's art can sometimes seem one of imprisonment. There is something profoundly telling, for example, in the way his brilliant patterns come to possess the individuals portrayed in his paintings. We are stitched into our environment: the wallpaper owns us, not the other way around. In Vuillard one begins to sense, as a kind of whispered intimation, the coming perception of the unconscious as a hidden ruler of the individual and of greater society as his maker. Yet this painter of small, cramped images also seems liberated in so many other ways. There is no greater comedy in Western culture than the eternally recurring belief that we are somehow freer than the masters of the past, when all we do is escape into new prisons in order to call ourselves free.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now