Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

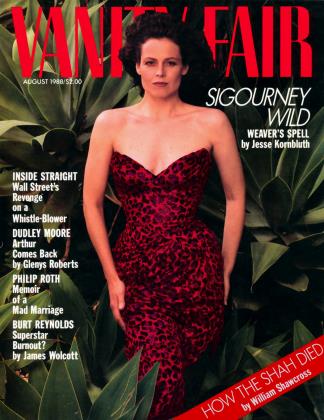

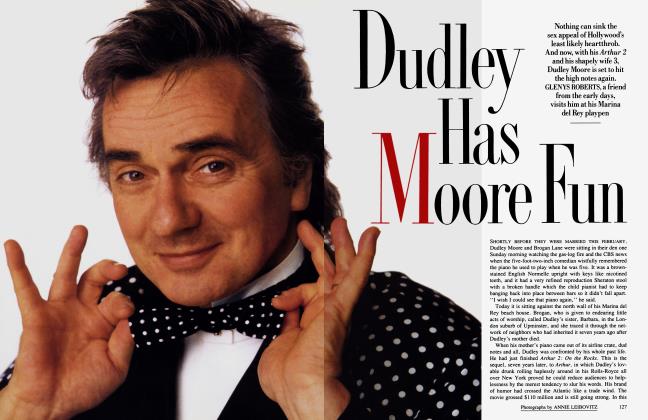

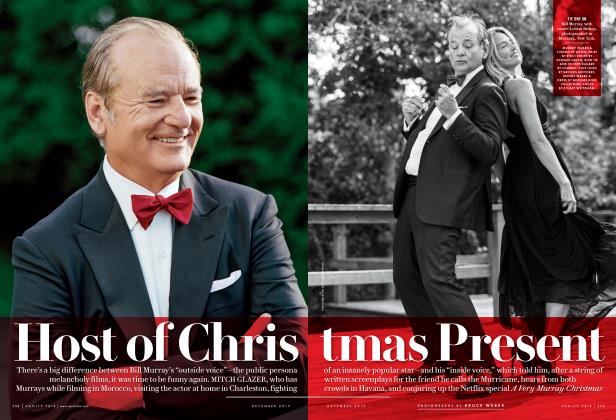

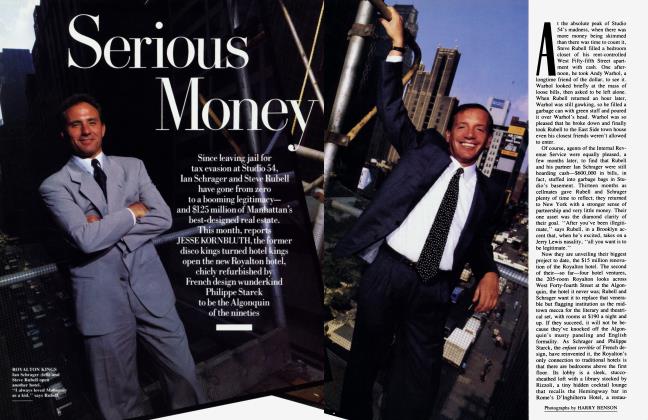

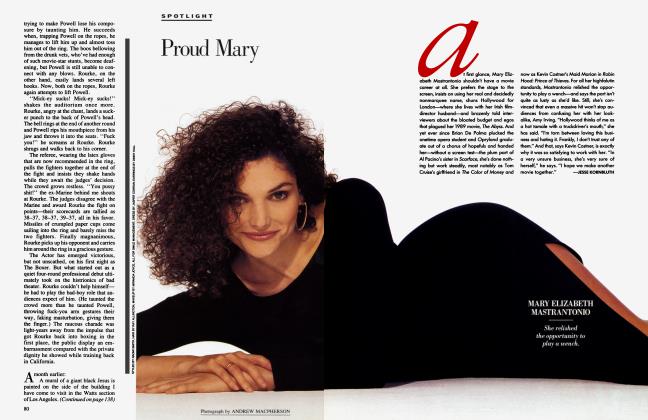

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter Ghostbusting and re-Alienating, the elegant, intelligent Sigourney Weaver has found a role that's big enough for her: as Dian Fossey, the primatologist who was murdered while fighting to save the gorillas in Rwanda. JESSE KORNBLUTH reports

August 1988 Jesse Kornbluth Annie Leibovitz Marina SchianoAfter Ghostbusting and re-Alienating, the elegant, intelligent Sigourney Weaver has found a role that's big enough for her: as Dian Fossey, the primatologist who was murdered while fighting to save the gorillas in Rwanda. JESSE KORNBLUTH reports

August 1988 Jesse Kornbluth Annie Leibovitz Marina SchianoThe door opened, but instead of Sigourney Weaver, there was a young man in an ill-fitting butler's jacket. "She'll be with you in a moment," he announced. "Come in." Then, oddly, he shook my hand. Another man sat in the living room, hunched over a small table. "This is Chris," the butler said, and disappeared. Chris grunted and went on writing "I love you, call me, Sigourney" on a stack of the actress's glossies. I took a seat on the banquette and fingered the Aubusson pillows. The price tags were still on them. They cost $1,095. Each.

Suddenly there was the crash of china in the next room. A man shouted. A woman shouted right back. And then there was the unmistakable sound of a body being bounced off a wall.

"What's going on?" I asked, now thoroughly unnerved.

"That's Jim," Chris said, meaning Jim Simpson, the theater director who has been married to Sigourney since 1984. "He's rehearsing a scene with an actress."

"It's very convincing."

"He's a very good director."

We sat in an uncomfortable silence, Chris's pen moving steadily. Slowly, the bedroom door opened—and a five-foot-eleven-inch apparition slinked in. Over tan pants and a silk shirt, Sigourney Weaver had wrapped herself in a huge shawl. In each hand, she held three unlighted cigarettes. As she camel-walked toward us, the actress who usually comes across as a latter-day Katharine Hepburn resembled Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard.

She moved past Chris. Just as she reached me, she wrenched the shawl from her neck. "I'm ready for my interview," she hissed, pushing her jugular vein against my face. With that, the butler reappeared and raced to the upright piano. Sigourney and Chris joined him, and, together, presented me with several choruses of "You're a Grand Old Flag."

As they sang, I twigged. The butler was an actor. The short, bearded man who'd seemed to be her secretary was actually her longtime collaborator, playwright Christopher Durang. And I began to get some insight into Sigourney Weaver. Days earlier, she'd suggested, through intermediaries, a theme for our conversation: "Escape from What I Am." The sincerity of her wish not to be herself was now clear enough. But why was someone this beautiful and privileged so anxious to rid herself of a natural dignity and easy grace that any sane actress would envy?

ON PAPER, SIGOURNEY WEAVER'S FLIGHT MECHANISM LOOKS like simple common sense. Her father is Sylvester (Pat) Weaver, the onetime president of NBC. Her mother, Elizabeth Inglis, trained at London's Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts and appeared in such classy films as The 39 Steps and The Letter. When their daughter was born in 1950, the Weavers lived in a Fifth Avenue apartment that, though expansive, was considerably less grand than their next home— the Sutton Place apartment once owned by Marion Davies. Naturally, they sent their daughter to Chapin, Brearley, Ethel Walker, and Mrs. de Rham's ballroom-dancing classes at the Colony Club. She came out, twice. And then, at the height of the Vietnam War, she enrolled at Stanford and, predictably, turned away from a patrician heritage.

But that's too easy.

For one thing, Pat Weaver's brother was "Doodles" Weaver, the professional cutup who started as the vocalist in the Spike Jones band and graduated to Topper and Bob Hope movies. For another, Pat Weaver was no reactionary. The inventor of Today and The Tonight Show, he tended to lecture his children about the excellence of Fred Allen as a comic; his favorite picture of his daughter shows her, rapt, as she watches a rehearsal of Peter Pan. And then there's the fact that, at fourteen, Susan Weaver dumped her given name in favor of Sigourney, an unseen character in The Great Gatsby.

Breeding plus exposure equals eccentricity. Though it seems she's always cast against type, Sigourney Weaver has turned out to be the right choice as the demon-possessed cellist of Ghostbusters and the gun-toting heroine of the Alien films, and, in the theater, as Bill Hurt's airhead lover in Hurlyburly on Broadway and Chris Durang's alter ego in any number of deeply Off Broadway ventures. Those films have grossed hundreds of millions of dollars; onstage, Sigourney has earned a Tony nomination and adoring reviews. There's only one gap, and it's a large one—the movie audience hasn't seen her as a credible modern woman since 1983, when she starred with Mel Gibson and Linda Hunt in Peter Weir's cult favorite, The Year of Living Dangerously.

This fall, that gap gets filled, as Sigourney stars in Gorillas in the Mist, a chronicle of Dian Fossey's crusade to save the gorillas of Rwanda (based, in part, on Alex Shoumatoff's investigation in Vanity Fair of Fossey's life and death). This role takes her from Fossey's sedate life in Louisville to her final destination as a murder victim, buried next to her favorite gorilla, Digit, in an African grave. Along the way, she is transformed from an eager neophyte to an impassioned champion of the defenseless. This is not a woman like the Baroness Blixen, who was portrayed with chilly, technical precision in Out of Africa by Meryl Streep, Sigourney's classmate at the Yale drama school. This is rugged, unromanticized filmmaking, with the star waking up in a tent each morning at 12,000 feet, chipping the ice off her bottle of Evian, and then climbing for as long as five hours to find her four-hundred-pound co-stars. You don't get much further from the Colony Club than that.

IT FOLLOWS THAT TWELVE WEEKS IN THE AFRICAN BUSH, filming six days a week and rehearsing on the seventh, were Sigourney Weaver's idea of a good time. "A sci-fi picture should be easier for an actress than the story of an amazingly complex woman," she told me after she'd kissed her comic co-conspirators good-bye and settled herself next to the pillows that would soon be returned to the decorator. "But, as it happened, the Alien movies were much harder. With Dian, I had so many facts. I didn't have to do it all in my head. And I'd finally learned what Peter Weir had tried to teach me—it's O.K. to do all the background work, and it's also O.K. to leave it at home. The important thing is to let things come out that are right for the part, not to drive it all. That's really what 'escape from what I am' means. Because it's fun to act. It's like going to the beach every day and frolicking in someone else's personality."

A producer once said she was too tall for a part. "Not if l paint shoes on my feet and play it barefooted," she replied, deadpan.

This approach to acting is a triumph of instinct over training. Sigourney had acted at Stanford, but then, she'd also lived with her boyfriend in a tree house and sewn elf outfits for herself—with pom-poms—on his sewing machine. Her intention, right to the end of her college years, was to get a doctorate in English and then teach literature. But in her senior year, as she was writing her thesis on the grotesque in Mark Twain, she noticed that her courses were uncommonly boring. She went to her adviser. "This is an exception, right?" she asked. "There's not going to be more of this?"

When he gave her the bad news, she belatedly applied to Yale; it was as "Mr." Sigourney Weaver that she was admitted.

There may have been worse places on earth than Yale School of Drama in the early seventies, but Sigourney Weaver couldn't think where. "I loved what I used to do in California—get together with a group of friends, take a play all over the Bay Area, and have fun," she explained. "I could never get used to how seriously they regarded theater at Yale.

Like: you had your own dressing room. Like: I once went up to a student director with a question.

He said, 'I'm not here to teach you how to act.'

This same director later told me, during the crunch, 'It's your ass, not mine.'

And it wasn't just her fellow students who baffled Sigourney. "At the end of the first year, the teachers have this evaluation, and they break you down," she recalled. "They didn't know what to do with me, because I wasn't your typical easterner. They'd already told me that they didn't like my clothes and that I was sullen. So for my evaluation I got this piece of muslin from the costume department and painted a huge target on it, and walked in with my little blazer and my little flannel skirt and opened the blazer and exposed the target. And I said, 'Hit me.' And they all went 'Heh heh,' and they took back everything they'd said all year. But they did add, 'Stick with light comedy. We don't think you should do anything serious.' "

Fortunately for Sigourney, she had made an exceedingly droll friend in Chris Durang. He too had discovered that frivolity was discouraged at Yale. In their second year, in an early draft of Durang's The Marriage of Bette and Boo, Sigourney played the part of a sensitive wife who laughs as her husband beats her. To no one's surprise, in her critical third year, Sigourney's unpopularity with the faculty meant she got only tiny, spear-carrier parts in Yale Rep productions. "I had to go into Yale College just to be in a play," she says. "I'm still angry about that."

In 1974, in her last months at Yale, her anger took the form of a visit to the placement bureau. "In addition to being terrifically talented, Meryl was immediately ready to be successful," she explained. "I wasn't. The woman in the job office said, 'But you have all this wonderful experience in show business.' I said, 'No, I don't want that. I want a job as a bank teller. Maybe if I'm near money, I'll feel more secure.' " Suddenly she understood what her father had meant when he'd called show business a crooked, awful enterprise, notable mostly for hustles and heartbreak. But she was determined to prove to her parents that she wasn't too shy or too tall to make it as an actress.

Having found an apartment in New York—in the same West Side building where she lives now—Sigourney went to the phone to announce her availability. Her first call was to a family friend. "Do yourself a favor, kid," he told her. "Get a job at Bloomingdale's." She knew how to translate that: "All my father's friends were trying to keep each other's kids from going into a business they knew was rotten.''

So strict was her refusal ever to ask her parents' friends for help again that, a decade later, she mumbled her name when she went backstage after The Gin Game to congratulate Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn. "She was generous about our performance," Cronyn recalls, "and as she left she said, 'My parents send their love.' I asked who her parents were. She told me. Well, her mother had appeared in a distinguished failure with Jessie on Broadway in 1940! I pulled her back inside and started all over." The friendship evolved to the point that the Cronyns invited Sigourney to Goat Cay, their retreat on Exuma. "No movies, no TV, no phone!" Cronyn exults. "We read, talk about the theater, and go swimming—I have great blackmail pictures of Sig in the buff."

Early in her career, Sigourney had sought work in Los Angeles, but, hating the way the actors talked about their jobs, she'd returned to New York after only two months. Now that her friendship with the Cronyns was blossoming, she was certain she had been right not to compromise. "I wanted to have Ralph Richardson's career, or Sir John's, or Jessica's," she told me. "If you care about great risks and great rewards, that's it." So she wasn't enthusiastic about auditioning, in London, for a part reportedly intended for Paul Newman. "A sci-fi movie wasn't what I had in mind," she explained. "What I was looking for was a supporting role in a Mike Nichols picture, something classy like that. I was a bit of a snob about it. But the day before I tested, I realized I could make the part anything I wanted—and that I didn't want anyone else to have it."

Alien may not have given her the career she wanted, but it did make her a star. At this point, Cronyn decided to send Sigourney to his agent. Sam Cohn, who blows hot or cold but never lukewarm, met her for lunch the day she called. Sigourney had another agent, and all her friends warned her that she'd be a nonentity on Cohn's client list, but she signed on anyway. Cohn not only pushed her, he listened to her when she told him about good projects for her less famous friends. Later, when Jerry Weintraub came to Cohn with an idea to turn stars into producers for the Weintraub Entertainment Group, Cohn remembered those recommendations; Sigourney effortlessly became a Weintraub employee. In the process, she didn't forget to acknowledge the single instance when it meant something to be her parents' daughter. "I named my company Goat Cay Productions," she told me, "because if I think of that place and those people, I'll be working in the right spirit."

CHRISTOPHER DURANG SHOWED ME A PICTURE THAT HAD been taken of him and Sigourney at Stonehenge. It was all but impossible to see their faces. "Sigourney insisted we pull our coats over our heads so we'd get in the Druid spirit," Durang explained. He didn't resist. By that time, he'd been indoctrinated in the importance of spirit—high spirits, usually—for his collaborator.

When they were plotting the end of their Das Lusitania Songspiel, for example, it was Sigourney who suggested that they throw vegetables at the audience as they sang "Welfare Mothers on Parade." When they did a fake magazine-interview-with-a-star at the Russian Tea Room, it was Sigourney who proposed ordering blini and smearing each other with caviar at the photo session. The necessity of writing their bios for the program of a Durang production led her to endorse a paragraph that gave her and Chris the same credits as the Lunts. "The Durangs live in Connecticut with their children, Goneril and Regan," the program noted. "Next year, they will perform together in Athol Fugard's Sizwe Bansi Is Dead."

Wire-service reporters dutifully recorded the Durang-Weaver marriage. They were not the only ones to find themselves on the wrong end of a Sigourney Weaver put-on. A producer once said she was too tall for a part. "Not if I paint shoes on my feet and play it barefooted," she replied, deadpan. At an Explorers Club auction to benefit endangered wildlife, she wore a flannel tiger outfit she'd sewn in college— and waved her tail to make her bids. Another time, she arranged to audition for Marco Polo Sings a Solo, by John Guare, a Yale friend. "She was to read for the fourthmost-admired woman in America," Guare told me. "She came to the audition—on the subway—dressed as a Norwegian milkmaid, with bright-red cheeks, wooden shoes, mid pigtails." She got the part. "How could she not?" asked Guare. "Sigourney is her own banana peel."

Curiously, it was this very goofiness which made her the ideal choice to play Dian Fossey. "The whole deal was based on filming in the mountains with the gorillas," explained director Michael Apted. "There was no question of building models. For this reason, the script was somewhat meaningless. We knew we'd have to shape the movie in the editing room, based on what the gorillas did—and how the actress played off them—as we were shooting." For this kind of work, an actress who can observe and improvise is necessary. If she's willing, like Carole Lombard, to make a beautiful fool of herself, so much the better.

But before Apted and producer Arnold Glimcher would hire Sigourney, they wanted her to see what extravagantly uncomfortable work she was undertaking. "We knew we'd be able to locate the gorillas at night, because we'd have mountain guides radio us where they slept," Glimcher told me. "By morning, though, the gorillas might have moved. They might circle, they might climb—the only way to find them is to follow their dung.

But finding them wasn't all our crew would have to do. In the preserve, the Rwandan government would allow us to bring only six people in—including the actress. That meant no makeup artist, no costumer. And it meant that, at high altitude, in pissing rain and freezing cold, Sigourney would have to schlepp equipment."

Sigourney and her potential employer went to Africa. They hacked their way through vegetation so thick that the trail closed behind them as soon as their guide cleared the path. It was hardly a romantic trip, but Sigourney was seeing Africa and Fossey through the veil of personal experience. She was certain she'd put on Fossey's clothes, wear a Fossey braid, and Fossey's gorillas would come to her like so many trained dogs. After all, as a girl, she had played with J. Fred Muggs, the chimp on the Today show—and J. Fred had developed such an instant attraction to her he'd tried to rip her dress off. At the very least, she thought, the gorillas would be physically present; she was getting tired of films like Ghostbusters and Alien, which called for her to react dramatically to terrors that wouldn't exist until the special-effects team laid them on the celluloid months later.

And then there was reality. "You climb for such a long time, you think you can't bear it anymore, you're sure your heart's going to burst— and then you go around the corner, and there they are." Sigourney's eyes were nominally trained on the Dakota apartments, just across the street, but she was far away, plugged totally into the Fossey Socket. "And you have all these human expectations that the gorillas will recognize you. And they don't. They don't care about you at all."

At the beginning, anyway. What Apted and his crew saw—and what the film records—is the actress's harrowing growth from novice to partisan, from scientist to spinster saint. "The big surprise for me is how immediately Sigourney was comfortable with the role," said Apted. "The animals really got to her. It was as if the spirit of that woman had transferred to this woman. It looked like a mystical loop—we all saw it. And that made certain things difficult. She always wanted to be with the gorillas, even when we had to shoot other scenes. I came to feel I was imposing on her relationship with the gorillas."

No one on the set much liked to think of the danger Sigourney was courting with this Fosseyan commitment. "These aren't tourist gorillas—they're strong, unpredictable, and not really used to people" is all Apted would say. His human star recounts only one frightening incident: "A gorilla got up, beat his chest, tumbled down, and gave me a big swat. I looked up to see where he was—and started making notes. I was hyperventilating, but I was so worried about looking like an idiot I stayed there."

There was a moment when one of Fossey's gorillas came over to Sigourney, checked her out carefully, and then gestured, as if to say, "No, it can't be." And toward the end of filming, gorillas who normally try to kill people who approach their babies actually presented their offspring to her. Neither triumph satisfied her. Arnold Glimcher stepped out of his tent early one morning to find Sigourney standing in the frozen mud, near tears. "What's the matter?" he asked. "I put on her costume, I put on her braid," she said. "And it was still my face."

If so, it is not the face of a Sigourney Weaver we have ever seen before. As youthful and hopeful as an expectant lover in the early days of her romance with the gorillas, she becomes God's harridan when poachers begin stealing and killing her charges. Her jaw juts, her face contorts in a rage so great she seems to have left acting behind. When poachers behead Digit, cutting off his paws and feet for good measure, she caresses the corpse and sobs so genuinely that Fossey's obsession suddenly becomes not only comprehensible but admirable.

After the small screening I attended, I cornered Michael Apted and asked him if perhaps the film contained a political metaphor.

"How so?" he asked, his eyes dancing.

In this film, I said, the poachers steal gorillas for zoos or kill them so collectors can display their limbs and heads. The poachers may even be responsible for Fossey's murder. But, in the end, her unshakable commitment is worth her martyrdom; the evildoers are routed, a species is saved. Perhaps that's an invitation for audiences to see the film as an endorsement of social activism—and as a huge fuck-you to America's eight-year wallow in thoughtless profit taking.

"Well, you got it," Apted said. "At the end of the day, I really don't give a damn about gorillas."

For Sigourney Weaver, the completion of the Fossey movie required one final rite. Before she returned to New York, she visited Fossey's house, where the brutality of the murder was still so palpable she had to flee. Understandably, she came home dreaming only of luxury—she wanted, she said, "to live in a first-class hotel for the rest of my life." Which meant, for her, resuming her marriage, decorating her apartment, and wondering anew if this was the right time to have a child. And, because a Mike Nichols film set in New York seemed like the greatest possible contrast to tenting in Rwanda, she signed on for a small part in Working Girl.

But the purity of purpose she'd brought to the gorilla movie carried over; for the first time in years, a director had to rein Sigourney in. "I was playing a Wall Street villain, and I had to explain things to the person I was double-crossing," Sigourney told me. "I thought a good villain would be really sincere. Mike had me act it like 'Oh, you found this. I should have shown it to you. Let's go on.' If I did it heart-to-heart, he said, it would be awful; a good villain lies all the time and doesn't even think about it. This felt uncomfortable to me at first, but it worked out great. Because I'd tried to play this woman sympathetically, to understand it from her point of view. And the truth was that she knew what she was doing and she didn't give a damn."

With that scene behind her, Sigourney felt truly home. Then, on the Nichols set, she saw a stuffed gorilla. "I had to go to my camper," she said, still troubled by her first major screen confrontation with fatal issues and real death. "I don't know what it was—the gorillas or Dian. I know this: no one could have been more surprised than me. Usually, by the time I've finished a movie, I feel I'm finished. But Dian keeps coming back."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now