Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

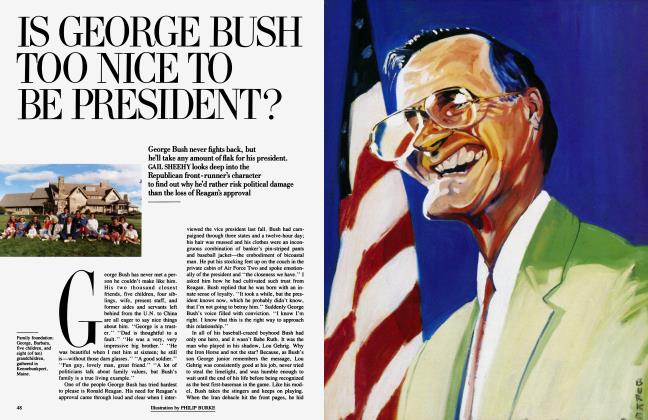

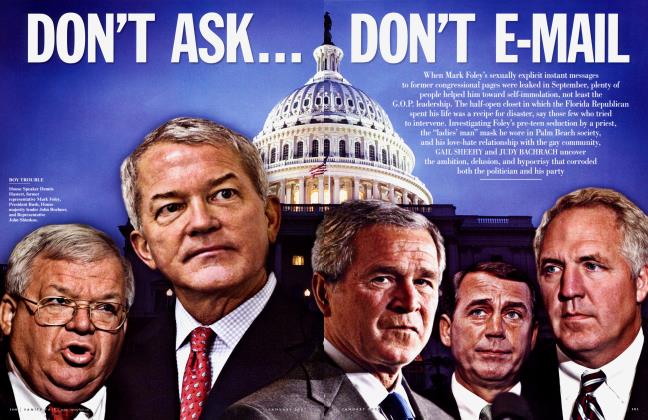

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBEATING AROUND BUSH

GAIL SHEEHY

The Bush campaign is as erratic as the candidate himself. It's up, it's down; he's tough, he's timid. GAIL SHEEHY takes a look at the vice president's A Team, to find out what they're telling him, what they're saying about him, and who's doing the dirty work

Nobody wanted to let George down. The humiliating defeat Bush suffered in Iowa last February—being skunked by the son of a grainelevator manager and, worse, by a showtime evangelist who had done no time earning his way up in the party ranks, zero—it was not the way a sixty-four-year-old patrician pol, veteran standard-bearer, and hell of a nice guy should go down for the last time. Fighting back became a very personal commitment for members of the Bush team.

At seven o'clock the morning after the Iowa debacle, the vice president summoned his inner circle to his hotel suite in Manchester, New Hampshire. One by one, they slunk in.

Robert Teeter, first among equals, overall strategist, is the sort of calm, congenitally moderate man who keeps twin gold ballpoints tucked in the pocket of his white shirt and fits naturally behind a big desk in his own office, swiveling to reach for polling data to support his arguments—not a man who looks comfortable in a hotel-room war council.

Craig Fuller, chief of staff in Bush's vice-presidential office, a tight-sphinctered Southern California conservative with a thatch of thick, straight-down brown hair, is known for being calm and methodical. He does not quickly react to events. "The more harried the circumstance,'' chuckles one of his old friends, Jack Flanigan, "the calmer he becomes.'' Fuller sat there like the dead, calm eye in the center of a hurricane.

Nicholas Brady, a long-boned, silver-haired man of aristocratic features, is closer to Bush than anyone on his team (with the possible exception of Treasury Secretary James Baker, whose shadow has loomed large, if intermittently, over the Bush campaign). An international investment banker, Brady is perpetually jet-lagged. He walks with a halt and a stoop, sweatercoated and horn-rimmed and affable, but displays the same tendency as Bush to get a little rattled and let his voice rise when his premises are questioned. He was certainly teed off that day. But no one felt worse than Lee Atwater.

Atwater, the guitar-playing Elvis of political managers, has tastes in combat that run to the sort of greasy-pig TV wrestlers who throw each other down on the mat while one wraps a snake around the other's throat. But when Atwater loses at his own game—political tactics—he gets physically sick. That morning Atwater lay so low in his chair almost nothing but his head and shoulders touched the seat.

"I personally felt horrible," says Atwater. "The buck stops with the campaign manager, which is me." He thought it might lighten the general mood if he said, ''Look, we got one lucky break—you came in third instead of second." He didn't say it.

Why six tough trainers can't make a fighter of George Bush

Bush stood before the core four in a terrycloth bathrobe. ''He looked fine," marvels Atwater. ''The guy is at his best when he's under duress. I was demoralized. He took charge."

''We can't waste any time pointing fingers at each other," Bush said, according to several accounts. ''This is nobody's fault. We're here in New Hampshire now, and all I want to do is do everything we can to win this."

Bush was talking to four masters of strategy and manipulators of image. Teeter believes that people don't vote on issues in presidential elections; rather, they respond to character, ''to whatever glimpse they get of what the guy's really like with the bark off." Brady is a deal-maker. Atwater believes reality is perception, period. Fuller is a prot£g6 of public-relations artist Michael Deaver (the former Reagan aide now planning to appeal a criminal conviction) and of Edwin Meese. ''There is nothing doctrinaire about Craig," says his first mentor, Steve Gavin, approvingly, adding in the corporatespeak the two share, "He's got his eye on the sparrow, but he stays very much in the background, always has."

Several decisions were made on the spot that morning. First, the pleas of the roadies who run the Bush campaign on the ground were finally heard: some of the trappings had to go, the thirty-car motorcades and the C-130 cargo planes dragging the equivalent of the set for Aida from your town to mine— Bush was being too presidential. And, second, Teeter began to impress upon Bush that now he had to take some risks. "He had been operating on the premise 'I have a big lead, and if I don't make any mistakes, I'll probably make it.' " But Teeter still didn't get a commitment from Bush to assert himself.

That first day after Iowa dragged them all through depression. Newsweek had just appeared with an article that rehashed Iran-contra and reopened the wound inflicted by its fall cover story on "The Wimp Factor.'' They cursed Katharine Graham, the publisher. A new speech writer was summoned. An emergency call went out to Roger Ailes, media wizard, who dropped everything and flew to New Hampshire.

"The impressive thing about George Bush to me," Ailes recalls, "was that he didn't lay blame. I remember him saying, 'I have the best group of people in the world, and if we can't do it, nobody can do it.' " Ailes, a highly paid, pugnacious political packager, responsible for selling the "new" Nixon, gets a kind of catch in his throat as he tells the story. "Those are magic words, after you've just gotten your rear end kicked twenty points."

Two days later the polls looked worse. The full Bush pro team of six assembled, scared. "Hey, we don't look too good," said more than one. "This is George's last time out," another reminded them. "We gotta pull this thing together," they agreed. So the team plotted how to turn their obstinate candidate around on the one thing he said he'd never do.

"You gotta go negative."

SIX AIDES IN SEARCH OFA CANDIDATE

A battle was taking place at the heart of the Bush campaign.

Atwater made the pitch to the vice president. The two have a kind of moth-and-flame relationship. Some who know Bush well say he probably would like to think of himself as having been an Atwater type when he was a young man—a tough, take-no-shit, stand-up guy, as they say in neighborhoods rougher than the Greenwich community of Bush's boyhood. But the vice president has a long-standing, public aversion to Atwater's Machiavellian specialty of negative campaigning: going for the personal, for the jugular. He allows it, but he doesn't want his fingerprints on it.

The team had already prepared the now famous "straddle ad,'' which attacked Dole for being on both sides of the issues. Atwater wanted to be ready to sock it to the Kansas senator if Dole aired his devastating "no footprints'' ad, which showed a man walking through the snow and making no mark, and ended with one simple, identifying line: George Bush. (The team is still terrified the Dukakis campaign will revive that commercial.) Bush had rejected the straddle ad. Now the rest of the team piled on, every single one.

"You could be creamed in New Hampshire. And if that happens, the fire wall in the South may not hold,'' they all told him. Bush asked about the polls. He had fallen three points behind Dole in two days.

"All of a sudden, negative advertising looks better to me,'' Bush said. "If you all think this is the thing to do, then go ahead and do it. I'm not—I'm the candidate.'*

After pushing Bush to take his first risk, everything else was tactical. His team turned the polls around in two days, and the following Tuesday pulled their man through. "Probably the best thing that happened to me,'' Bush would later gamely tell audiences, "was getting my brains beaten out in Iowa.''

The vice president is at his very best in the face of danger or defeat. He becomes the bullish underdog who must win, instead of the timid, noncommittal observer. He is also Mr. Fair and Loyal, collegial to the core. He didn't fire Atwater over Iowa. And he won actual affection from the normally cold-blooded Ailes.

From then on Bush and his pro team bravely battled back, beating the man many think of as the soul of the Republican Party, Jack Kemp; kicking aside A1 Haig; putting away "Pierre'' du Pont; exposing Pat Robertson to ridicule; and, finally, besting Mr. Republican Insider, the redoubtable Bob Dole, and his accomplished, telegenic wife. Nobody, not even his closest advisers, had really believed George Bush had it in him to win so many primaries, and so fast. The old preppy with his murdered metaphors and square spectacles and much-maligned manhood had made a decent candidate after all—surprise!

I take as my premise that the campaign is the candidate. Like beams around the Sun King, the people he selects as his inner circle radiate aspects of his own character. And the way his campaign is managed is a prototype for the way he would run his presidency.

Bush's risk-averse campaign and his relationship with his inner circle reflect the very qualities that laid the nomination at his feet, coronation-style, six weeks earlier than expected, and that got him so tangled up in the robes of succession he began tripping over himself.

By late March, George Herbert Walker Bush looked like the crown prince preparing to ascend to a throne secured by the Republican Party. He began to sound almost comfortable with himself—for the first time since launching the longest presidential campaign in history. The night Bob Dole folded his candidacy, removing the last (particularly noxious) obstacle to Bush's rightful G.O.P. inheritance, the vice president was at his all-time best.

Reagan has always been the star. And stars don't like an understudy to get their part

Wriggling all over with his good fortune, Bush entered the vast auditorium of the Sentry Insurance Company in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, stumbled up the steps to the podium, and surveyed a crowd of 3,500.

"Wow," he said.

He told the crowd he was late because he had called Dole to thank him for his generous statement. "Worthy warrior, a tough competitor," Bush said, congratulating his archrival as nobly as a knight, "and having been through a similar experience, Barbara and I, eight years ago, I know how disappointed he and Elizabeth feel." His empathy came through as totally sincere.

Oh, what a triumphant night it was. Bush had really begun running in 1979. He had lost not a moment after Reagan's reelection to stock the office of the vice president with the men who would form his own election team. This night was the payoff on Bush's strategy of playing loyal second to Reagan through thick and thin, the ultimate triumph of organization and money and contacts.

"These two days," Bush told audiences in Wisconsin at the end of March, "have turned out to be two of the most significant days in my political life." The only dark cloud was the carping among members of the national traveling press. Kept beyond a boom mike's distance from anything but the most staged "spontaneous" events, the frustrated journalists were a potential source of backlash whenever Bush made a mistake.

The Bush team's media strategy was to move the candidate through twenty-minute airport sessions with local reporters. The national press, although paying for the campaign plane, was permitted only to send in a pool reporter—who was then ignored. The Washington Post correspondent had been waiting a year and a half for a one-onone interview with Bush. To get an audience, one had to beg.

The NBC correspondent went to Bush's deputy press secretary at 5:30 P.M. on the day Dole conceded.

"They've ordered another satellite for a second feed: Vice President of the Free World Calls Former Rival. Can we get a reaction from the veep?" Everyone overheard and grew excited—maybe a tidbit tonight?

But the aide stalled the press. Media veterans of the campaign knew they would soon be marched back onto the deluxe Pan Am charter for another forced feeding—"Hi, David!" "How's it going, Gerald?"—and the perky flight attendants, who by then knew everyone's name, would pout if not permitted to lay out the napery and ply them with a choice of salmon in champagne sauce or medallions of veal. But what about access?

Bush had already levitated to his hotel suite, surrounded by his usual cordon sanitaire. Not until the last possible moment did press liaison Alixe Glen get back with an answer after consulting with Bush on the request for a reaction to the night's momentous victory.

"There will be no photo op. He has a very small room."

The mood on the bus turned evil. "Poor Poppy—not another night in the Holiday Inn." "Such a crock of shit." "Hey, Alixe, we were hoping he'd replay what he really said to Dole when he called him: Whipped your ass, didn't I, you one-armed son of a bitch?"

"The vice president doesn't talk that way," Glen replied.

"Yeah, sure."

What did the nearly anointed successor to the presidency have to care about the press by then? Let them eat veal.

G-6. Such a wonderfully worldly, arrogant neologism, this play on the G-7 group of industrialized nations. I had heard so much about this smart team and their stunning record in electing and protecting Reagan, I went around to get to know each one, hoping to wrap up the story by seeing them at work together.

LEE ATWATER, the anti-establishmentarian working for the most blue-blooded northeastern-establishment star in his party, contrasts most boldly, almost laughably, with Bush. But the campaign manager reflects both Bush's mean and playful sides. "A bom schemer," according to his high-school buddy and college roommate, Mike Ussery, Atwater was the much-loved rebel leader of the school misfits. He could do a split and sing knock-yoursocks-off black music; he was drawn to the fiery evangelists who gave tent shows, and the misfits cast as heroes and villains in his beloved wrestling matches. He went to the virtually no-count Newberry College for the simple reason, he admits, that it was the only place that would let him in. But all the while, on the sly, he read deadly-serious books. From The Prince he developed a taste for hard politics. And he learned the game from South Carolina's rough-hewn senator, Strom Thurmond.

Atwater's greatest dream is to run a duly "outsider" candidate who hasn't come up through the system. So what is this rebel without a cause doing at Bush headquarters, where there are so many beautiful blond cookie-cutter interns it looks like the student union at Princeton? Cycles, it's all about cycles, and Atwater expects he'll have to wait sixteen years for the next major cycle.

Meantime, he spices up the regulation gray-suit attire with Eau Sauvage cologne and skinny orchid ties that look like reptiles. His natural greeting to a girl, as all women are called, is "Hey, baby." But for all these colorful distractions, Atwater is known as probably the most talented political tactician in the business today. He loves a fight, and as he talks he keeps brushing his nose, like a boxer.

More senior strategists say Atwater needs "adult supervision." Indeed, his office is bracketed by those of two restraining influences—Bush's son George and deputy campaign manager Rich Bond. But even colleagues dubious about his maturity (he's only thirty-seven) allow as how Lee Atwater is the necessary firecracker in a campaign that lacks Atwaters. "He likes the opposition to think he's just a half a tick off," says Bill Carrick, a Democratic consultant who has faced him in many contests, "capable of the equivalent of a nuclear meltdown."

Atwater seems to be most closely associated with Bush around the candidate's "little meannesses"—those spasms of pique that come across like kicking sand in the face of a muscle-bound beach bully. Culturally deprived of populist profanity, Bush slums through other cultures for the right language. Much has been made of the vice president's nasty remark about Geraldine Ferraro after their '84 debate. But Bush himself made the most revealing statements on the David Brinkley show two weeks later.

"You said you'd kicked her ass," Sam Donaldson reminded the vice president.

"I didn't say that," Bush sniped back.

"What did you say?"

"Well, I've never said it in public!"

Bush's pant leg in his mouth, Donaldson dragged the candidate through the facts: he was in public, surrounded by press, and his remark was recorded by a news camera.

The vice president tried to wiggle out of it: "Well, if I'd wanted to say in public the statement that I have never repeated, I would do it."

So, in his mind, there's a public and a private George Bush. The private Bush, according to close friends and aides, yes, does like to throw around smutty language and locker-room jokes. Unlike Atwater, though, he's not comfortable being a bully in public—and it shows.

CRAIG FULLER, who heads up O. V.P. (the Office of the Vice President), reflects another side of Bush: "Total C.E.O., cold, calculating, steel-jawed," as a prominent conservative describes the Bush behind the scenes. The kind of chief executive who appears to his employees as a real softy, then shuts his office door and barks orders to his lieutenant: "Gotta close a factory, excess 1,200 people—don't come back to me until the doors are locked." Fuller, who has a reputation among insiders as a master backstabber and "silent user," may be the last man in the White House who came in with the Reaganauts in 1981—the consummate political survivor. "He was past thirty when he was bom," says his friend Jack Flanigan. "But the amazing thing is Craig works seven days a week and he doesn't bum out." Indeed, Fuller has the ultimate White House family: a wife who works there as well and no children.

Starting with an internship in Governor Reagan's office back when Fuller was a college sophomore, he has attached himself to powerful men. "Craig greatly admired Meese from the beginning," says Peter Hannaford, his former boss and the surviving member of the Deaver-Hannaford P.R. team. Meese invited Fuller into the White House. He worked Erst for Reagan, switching over to Bush on January 1, 1984. Like Bush, with whom he has been involved in shadow White House dealings, Fuller knows what is required, executes it according to orders, and leaves no fingerprints.

In a long interview, I asked Fuller about charges that a makeshift U.S.-Israeli airlift existed in the mid-eighties to ship weapons to the contras, through Panamanian airfields, using contract pilots who then refilled the planes with Colombian cocaine—their payoff. "It's difficult to run a covert operation without dealing with the underworld, wouldn't you say?"

"It is very difficult to run an undercover operation without dealing with the underworld," Fuller affirmed, "if you exclude the C.I.A. And one of the problems that we had was, once we were unable to operate or run a covert activity—the C.I.A. was frozen out of it essentially by law—all kinds of people, nefarious people, got involved."

From pilots to airport managers, all the way up to Honduran generals, I suggested, people who have to look the other way if you're going to get cooperation for secret gunrunning operations?

"No one should have been looking the other way," Fuller said blandly. Then he made an uncharacteristic disclosure. "One of the reasons that eventually Felix Rodriguez [the C.I.A. agent who helped Oliver North run the secret contra-supply network] came to see Don Gregg [Bush's national-security adviser] was to say, 'We've got some very bad actors in this whole thing.' "

Continued on page 238

Continued from page 207

But even when an interview covers provocative ground, Fuller never loses his cool. He simply shuts off contact to the veep to anyone who doesn't serve his purposes. As a Bush disciple, he belongs to the Smile Now, Stab Later school of operation.

George and Barbara Bush, for instance, have a reputation among G.O.P. insiders for being vindictive. "I think Bush is a very mean guy, meaner than Dole,'' says a movement conservative who worked for Kemp. "Anybody in the 'Not Bush' wing of the party will pay," he predicts. Dole's subalterns have already been kicked out of party jobs. When I asked a close aide if the veep and his wife talk tough in private, he chuckled. "Hell, yeah." Several of Bush's advisers acknowledge he is indeed capable of holding a grudge; he apparently has a long memory and a long list.

"He's the kind of guy who really wants everything to work out," explains Roger Ailes, a practiced student of character. "He would rather be a nice guy, be sweet, have everybody like him, just mind his own business and not get in trouble. But he's perfectly capable of shutting the door and saying, 'That's it for you. Boom. You're gone. History.' "

ROGER AILES is the new kid on the team. After seven months of negotiations, he came on board for $25,000 a month, more than twice what Atwater makes, plus a percentage of the TV commercials that will probably exceed a million dollars. He overflows his high-backed desk chair at Bush headquarters, where he now spends several days a week. His batikprint tie is pulled down, and the blackand-white goatee lends just a touch of the sinister. With Orson Wellesian intensity, his eyes—now wary, now good-humored—read the person before him until Ailes decides if he'll play you or fight you. One thing he vows not to do, because he doesn't trust them: Never break bread with the press.

"I'm a pacifist until hit, and then scorched earth is too mild," he promises.

It's a long way for the son of a factory foreman from Warren, Ohio, to the highflying howdah of Air Force Two. "Most of the guys I went to school with are still out there," he says, "lying under cars with grease still dripping on them. I stood up."

A call comes in from one of his friends asking him to speak to a group. "I'm down at Bush HQ trying to save America," he says. "Is there any money in this?" He props a pin-striped leg on a chair and slowly, like a metronome, taps his foot. He keeps one hand in his pocket. "Nah, I'd just as soon come back in a limousine. I don't know that we need to do a private plane."

While not without charm, Ailes is no debutante's dream—as Bush once was. Ailes was also turned away as a naval flier because of a childhood illness. His near hero worship of Bush is easy to understand. He was particularly struck by watching Bush's simple humanity during a strategy meeting up at Kennebunkport.

Bush was tense, getting ready to do the David Frost interview. "Is he going to get on all this psychobabble bullshit?" the vice president asked Ailes. Before he could answer, the phone rang. Bush interrupted their meeting. "I just gotta call this guy, California, guy got fired yesterday— I really feel bad about him." Ailes marveled that Bush should take out five minutes to cheer the man up.

"I said for a minute, 'Is this good or bad?' " recounts Ailes. "But I sort of admire it. Better to have a guy with a heart in there."

He had his work cut out for him in restyling Bush. Here was a candidate who had flatly refused a speech coach for years. Furthermore, says another senior campaign consultant, "George is a great guy to sit down at a dinner with. He'll answer all your questions and be fine. But just put him in front of a camera with lights and a producer, and—freeze." Ailes gets the credit for slowing down Bush's speech, which lowered his voice, and made the 1988 Bush sound more forceful than ever before.

In the world according to Ailes, "my candidate may think AIDS is important, but if polls show the people don't think it's as important as education, then my guy has to make education the issue." But Ailes will go to almost any length to keep issues out of the campaign, believing that no candidate can speak out strongly on anything without being "eaten alive." His job is to project a winning George Bush personality.

So, just hours before the now famous interview with Dan Rather, Ailes was waiting for the vice president when Air Force Two returned to Washington from the campaign trail. Bunching down to shove in beside him in the limousine, Ailes made his characteristically apocalyptic pitch: "Mr. Vice President, CBS wants to send you back to Kennebunkport. They're going to do you in on Irancontra."

Bush didn't take the bait, telling his aide that he could answer the questions about Iran-contra. But Ailes eventually convinced Bush he had to be at least prepared to hit Rather back on his weaknesses. Bush delivered the verbal jab on national TV, and then described the confrontation as "combat." For Ailes's purposes, it was a calculated act meant to neutralize "the wimp factor," as well as to shut off the media's inexhaustible supply of questions over Bush's role in selling arms to a terrorist government.

A very different Bush was seen through his interview with Ted Koppel on Nightline. Ailes didn't get to the candidate until thirty minutes before showtime, so there was no strategy. The man we saw opposite Koppel was the real George Bush: ducking and weaving, smiling miserably through his frown lines, blabbing too much detail as if hoping he could make time run out. Following the interview, the vice president publicly critiqued his own performance, and decided he wanted to come out "somewhere between going ballistic with Rather and being too passive with Koppel."

"Combat"? "Going ballistic"? We're not talking about war here, or even a tense summit with Gorbachev, but about the now commonplace experience of being interviewed live on TV by another white male American. Bush constantly uses such exaggerated language. After besting his Republican rivals in debate, he claimed, "I deserve a Purple Heart" for the effort.

When called upon to assert himself, Bush either underreacts or overreacts. He usually starts by shrinking into silence; alternatively he'll come back towel snapping like a prep-school smart aleck, and follow up with an obsequious—and usually implausible—apology. Sometimes he goes on to wave his arms about in imitation macho. This is a man who does not know how to measure his own forcefulness.

ROBERT TEETER, of the six men, is the most compatible with Bush. "They're the same personality type," says Atwater, "so Teeter is very good as a communicator with the candidate." Mild-mannered, cautious, broadly liked but often criticized for being too passive, Teeter is the wizard who keeps the polls that dictate Bush's message.

Of the twenty-five Republican Party operatives interviewed for this story, all acknowledged the lack of a driving Bush ideology or theme. Teeter admits, "I've spent a lot of time in the last year or two saying, 'What do you want to run on?'" One of the few issues that really excite the veep—he's fired off many notes to Teeter about it—is nuclear proliferation on the Indian subcontinent. Not exactly an issue to pass the shot-and-beer test: when two strangers knock elbows at the bar, do they say, "So whaddya think about this nuke-u-ler proliferation on the Indian subcontinent?"

The one clear message Bush had been taking around the country was "I want to be the education president." Then he would torture his grammar and snarl his syntax until people wondered if he was doing a stand-up on Saturday Night Live. According to Teeter, Bush truly believes that education is the panacea for all social ills.

When that message fell flat, Teeter sent Bush out to fight for the ethnic blue-collar voters who were pivotal to Reagan's winning coalition. "Get them the same way we got them last time—on patriotic and national-security issues," he urged. So Bush went after Dukakis on the Pledge of Allegiance in schools, and later tapped deep anti-Iranian sentiment when he championed the captain of the U.S.S. Vincennes' s action in shooting down an Iranian passenger jet.

The two other G-6 members are ROBERT MOSBACHER, a rich oilman who is not involved day to day with the campaign, but who raised over $23 million for Bush during the primary season, and Nick Brady.

NICHOLAS BRADY is the only real peer, in accomplishments as well as age, on the Bush team. Where Atwater greets women with "Hey, baby," Brady uses "Hi, kiddo." The worldly banker, whose family has owned the same 2,200-acre farm in New Jersey for the last seventy years, is the only member of the Court of St. George with enough seniority "to push firmly and consistently against the grain of the candidate," according to insiders. Brady, however, has no experience in running even a local political campaign. And he may be too good a friend. When everyone else was hammering away at Bush to separate himself from Reagan, Brady didn't. "Everybody he mns into says the same thing to him," Brady reasoned. "I think one thing if you're a friend is to not needlessly aggravate your friend."

Put them all together, the supercautious moderators—Teeter, Fuller, Brady, and Mosbacher—and the aggressors, Atwater and Ailes, and the chemistry of the original team produced a high-voltage field around the candidate. No one of its members dominated. And so long as events did not require active leadership, Bush made this clubby circle work for him. Indeed, its fragmented collegiality mirrored Bush's own character. This is the way he has always shielded himself from confrontation and avoided blame when things go wrong.

It is when "Bush comes to shove," as Washington lawyer Len Garment put it, that the flaw at the center of the campaign is exposed: unless Bush is forced to act— forced by imminent and certain defeat— he will only react.

Even during those two "most significant days" of Bush's political life, while the vice president posed in a U.S. Navy "Bearcat" at an aircraft museum in Wisconsin, a major news story was breaking back in Washington that cried out for Bush to act.

"Will he answer questions?" reporters gathering for the photo op wanted to know.

"No, it's not set up for P.A.," an aide fibbed. He went on to explain that the veep would be presented with a leather aviator jacket. "As most of you know, he was a W.W. II navy flier."

Bush grinned when given the Eagle Squadron jacket, murmuring, "Perfect, perfect." Cameramen knocked one another over to scramble upstairs for the second photo op—"He's puttin' the jacket on!" Then Bush climbed into the cockpit of the old propeller warplane. The cameramen called for a pose.

"You want the Red Baron?" Bush took off his glasses and thrust his arm in the air, ebullient as a kid playing war, but he couldn't quite synchronize the V-for-victory sign with a smile. "I hope I can get outta here," he fretted as he climbed out of the cockpit backward, the first leg awkwardly dangling in search of a foothold, "without falling."

And then it happened. While Bush stood with his museum tour guide, chitchatting about improvements in radar, a news bulletin came across the supposedly nonexistent public-address system: "Two members of the Justice Department have unexpectedly resigned in protest over the Wedtech scandal.

The traveling media strained at their rope barricade. Would the vice president please comment? Bush ignored them. Then said he hadn't heard the news. Then said he'd heard only rumors. Then pushed on to the replica of a plane Chuck Yeager had flown for the army.

"Neat," he exclaimed. "I'm dying to learn about this thing." His forehead wrinkled. "How does one go to the bathroom in it? That's the inevitable question." The only statement the vice president offered that day was "In a space station, how you handle waste, that's a real problem."

The alarms didn't go off then. Bush and his campaign cabinet immediately settled down for what promised to be the long, no-message, no-error juggernaut to the White House. They went to New York on April 12 for a high-glitz fund-raiser. The party was being organized at the Plaza by that hotel's new owner, casino king Donald Trump.

The Bush party didn't actually stay at the Plaza (they prefer the Waldorf), and Pete Teeley, then the candidate's chief spokesman, couldn't even bestir himself to get over to the Plaza to catch Bush's speech. "The only reason to go over is to see who Trump gets out at $1,000 a pop," he told me.

It was largely a Mr. Wall Street and Mrs. Mink Stole crowd, ornamented with some of Bush's old U.N. contacts, a quartet of bowing Japanese businessmen and matching Korean wives in billows of crimson-and-turquoise silk organza who entered looking like floats. A strident society orchestra played "I Love New York" repeatedly until the fanfare began. Trump came first, his set-back chin and ducktail silhouetted in the blinding spotlights, Ivana on his arm, her shoulders padded out like pillow bolsters. As they moved around the receiving line, Trump boasting that his book had sold more copies than Tom Wolfe's, the vice president came into view behind him. Trump's introduction left no doubt who was king of this mountain.

"We're here for a little talk from our next president."

Bush stepped up to celebrate the status quo. Some remarked with delight on how much stronger his speaking style had become. He was beginning to sound like a man with a message. All that remained was to spell out what that message was.

The picture stays with me of Teeley, back at the Waldorf, as he lounged in a velvet Louis XVI armchair in the Bush team's lavish mauve-and-royal-purple suite. The cool gray eyes of this postW.W. II English immigrant, known inside the media as the Sultan of Spin, were half-closed—ho hum, winning is such sweet boredom—his posture emblematic of the whole Bush team's smugness.

"You know, now it's like we hardly pay attention to results—he's been running two-to-one or better for so long," Teeley told me. Faint, muffled cries could be heard from far below us, in the street. "Demonstrators." Teeley flicked his wrist, the way colonials do out of habitual pique with the insect life of the lower orders. "We get 'em everywhere."

What are their complaints? I asked.

"Central America. Contra aid, mostly." My mind leapt to the image of Richard Nixon barricaded inside the White House by buses so he couldn't see the massive anti-war march on Washington. Or Ronald Reagan watching TV sports while the whole country was fixated on the Iran-contra hearings. Bush presumably would be equally unresponsive: hear no protest, see no evil, speak only spin.

For the next three weeks I tried to meet up with the Bush team and watch them all together, in action. One by one, they agreed to the proposition, and passed me on to the next member. Suddenly, insistent calls were initiated by Craig Fuller's office—he wanted to see me. After a long interview, he promised to give my request serious thought. Whereupon his secretary sent me back to Atwater. Then Teeley's secretary phoned to say, "Pete is the one who decides."

Finally, Lee Atwater suggested I fly to California—at least three of the core group would be there. I flew to Los Angeles. Atwater never showed. Nor Teeter. Pete Teeley was back in Washington sulking. Only Fuller was there, and he said, "I'm off duty; this is home turf." I told him about Atwater's suggestion to "c'mon out to California and sit in on a meeting on Air Force Two."

"Sorry about that," said Fuller. He didn't sound sorry.

I couldn't find the Bush campaign, only the vice president sitting next to Barbara on the little chairs of high-school sophomores, trying out the role of "education president."

At that very moment, because of Bush's failure to confront the Meese question, G-6 was coming apart. A battle was taking place at the heart of the campaign, a battle for George Bush's character. For several weeks, half of Bush's hotshots had been running around behind the scenes whispering to the press about how deeply and personally disturbed their man was by the cloud hanging over the attorney general. When Bush himself was unable to deflect questions about Meese, he copied Ronald Reagan's old denial technique: "I don't want to think badly of him." In one moment of particularly rash underreaction, Bush was quoted as saying that if Meese was cleared of criminal charges by the McKay report, he would consider hiring the attorney general in a Bush administration.

From that day in the aircraft museum at the end of March, when Bush ducked the issue by prattling on about the problems of disposing of doo-doo in space, until July 5, when Ed Meese announced his eventual resignation, the vice president never did confront the problem.

But Pete Teeley finally reached the point where he couldn't keep his mouth shut another moment. For all his hardboiled demeanor, Teeley really loved the vice president. He was the one Bush would call for most often when the candidate was trying to while away tedious downtime in hotel rooms. Along with Atwater, he was always pushing for a more aggressive, confrontational stance—to get the jump on Dukakis, to distinguish Bush from Reagan. And now his man could no longer make a speech about ethics without being hounded about Meese, or a speech on drugs without being hammered on Noriega. So Teeley went on the record to protect the vice president from himself. He complained that the White House was creating a serious political problem for Reagan's loyal number two.

This violated an edict put out by Bush himself. No one on his team was to go to the White House and insist that Reagan and company consider how their policy decisions might affect Bush's presidential chances. And Bush adamantly refused to go himself. Some in his circle had wanted to use the press as messenger to complain about the White House's insensitivity (on Meese, on Noriega, on the plant-closing bill), but Bush nixed that too.

Teeley had finally climbed out on a limb, and Fuller spotted his chance to saw it off. "It was just a question of people going the other way, essentially Teeter and Fuller," Teeley told me after resigning in frustration. "Those guys never wanted me back last year. They wanted the inside track, all the time." But after going all around the G-6 circle to complain that he wasn't being plugged in— couldn't even get advance copies of the veep's speeches!—Teeley finally went to the top man himself. Bush took action by not taking action. He let Teeley resign.

"I think he feels very badly about it personally," Teeley told me later.

I asked Nick Brady, "Did this hurt Bush?"

"Not at all," he said dryly.

The cold-blooded, cautious, C.E.O. model had won out. Shortly thereafter, Fuller and Teeter had Bush tiptoeing again.

Whither G-6? I asked Brady.

"Nobody was in command of G-6 before, and there isn't now," he barked. "The idea that there are aggressors and non-aggressors—a lot of baloney. In G-6, everybody is on every side of every argument. So you talk to four different people and you get four different answers."

That's exactly what Republican insiders diagnosed as the chronic ailment within the Bush team—no center. The group had two ways of reaching a decision: either everyone was gotten together in a room to reach a consensus on whether to do A or B, and to then try to sell their decision to Bush—often too late to matter—or, failing unanimity, they fell back to logrolling (agreeing to do A and B, or to do nothing). This is the formula that resulted in Bush's mixed message. The Bush organization is essentially the same team that was a marvel of discipline during Reagan's re-election campaign. Yet gathered around Bush, these advisers fell into a different pattern—flailing about between thrust and drift, alternating between smugness and panic. What was the problem?

Simple, say observers. In Reagan, they had a man who had done nothing but take direction all his life. "If we told Reagan to walk outside, turn around three times, pick up an acorn, and throw it out to the crowd, we'd be lucky to get a question from him asking, Why?" notes one highly placed source.

Bush is different, says the source. Altogether different. Bush doesn't take direction.

Not a few times, admits Ailes, Bush has told him, "Go to hell! I'm sixty-four years old and I'll do what I want!" And Brady points out that "for three years he has resisted everybody that said, 'Now you gotta change.' " It might seem contradictory at first, in light of Bush's deferential, often passive appearance, but his resistance to taking direction is an additional dimension to his pattern: Bush doesn't try to dominate others, but he refuses to be dominated—except by the authority figure in his life (first his father, most recently Reagan). This is the unspoken bond between Bush and his inner circle—as if he'd told them, "I'm a decent guy, and I don't want to be pushed around. If you push me around, then you force me to exercise my leadership and speak up against you."

The flip side of this problem is that Bush seems to have no clear direction of his own. One of the G-6 members was asked by a skeptical man of talent he was trying to hire, What is Bush really like? Give him a mission and he'll carry it out, the man was told, but Bush won't think it up on his own.

That analysis puts in a new perspective Bush's now well-advertised behavior when he was shot down as a naval pilot in W.W. II. He is, properly, given much credit for carrying out his orders after being hit, despite smoke belching out of his engines and through the cockpit. "I had to finish my bombing run," he told me, simply, and so he continued his dive and dropped bombs on his target—fulfilling the mission he had been given.

And once he's been given a political mission, no one can pull him off even when it's over. For example, after James Baker called off Bush's '80 campaign, Bush kept right on dancing around the campaign barnyard, speechifying, like a political chicken with its head cut off.

If a campaign is the prototype for management of the presidency, then the Bush campaign thus far is disturbing. Bush won't take direction as a politician. But neither will he give direction as a leader. And he shows every indication he is afraid of Ronald Reagan. In a long interview I did with the vice president in the fall of '86, his very personal, emotional need for Reagan's approval came through loud and clear. As with his father, any authority figure seems to have the potential to neutralize, if not paralyze, Bush's own initiative.

And Reagan has not missed many opportunities to put Bush back in his place. As Bush himself admitted during their '84 campaign, after the mildest attempt to speak with his own voice, "I tried once, and wow!" At issue was Bush's statement "Never say never" on the subject of raising taxes; "a president should not foreclose his options." Reagan slapped him down, issuing the statement "I'll raise taxes over my dead body... I'm not preserving my options." It was sufficiently traumatic to the vice president that he brought up the discrepancy on the Brinkley show and related it immediately to emasculation: "I don't want to show a lack of manhood here in the last fortyeight hours."

Reagan has always been the star. And stars don't like an understudy to get their part. Bush's Hollywood playmate, music promoter Jerry Weintraub, laments about his pal's predicament, "It's like closing an act for Sinatra."

"I've never worked with a candidate with less ego," sighs Ailes, "and sometimes that works to his disadvantage. He's so self-effacing, he never puffs up or anything." Ailes trashes Bush just to try to get a reaction.

The acid test of leadership arose in the first week of June, when the Bush circle all agreed the time had come for their man to cut the Gordian knot tying him to the president. And the first week of June was a disaster for Bush.

A little-known governor with a funny name, a marathon runner formerly dubbed one of seven dwarfs, had pulled well ahead in public-opinion polls. The smart team around Bush was in shock. Top G.O.P. strategists admitted they hadn't seen such high "negatives" since Nixon days. "George could fall across the finish line first—that's about the best hope we have," one moaned. Jack Kemp said flatly, "We can't win with an issueless, themeless, idea-less campaign." And the vice president himself, even beneath his tan good looks, began to show the pallor of panic.

So what did candidate Bush do? He began giving us dial-an-image. Day by day, even hour by hour, he switched faces and mixed messages. It was as confusing and arbitrary as a TV viewer flipping channels with his remote-control zapper.

One hour Bush sounded as if he were ready at last to "spell out" his own views and stand up against the Reagan administration's sordid deal-making with Noriega. But—zap—only hours later, Bush backed away. One minute he was delivering a blistering attack on Dukakis. Zap. The next minute he was purring about nonpartisanship. Zap. Bush as Bully. Zap. Bush as Pussy. Zap. Bush as Ronnie Wannabee.

Just days after promising, on June 6, that he would make "a shift"—soon—to move out from under Reagan's shadow, Bush was publicly complaining in California that he didn't want to be inching away from President Reagan at all. Asked by ABC's Peter Jennings if he would like to distance himself from all unpopular administration policies, Bush piped up, "Well, if I can work out that magic formula, yeah, I'd like to do that." He told reporters, "I know I have to spell out very clearly what my priorities are, what my passions are.. .but I'm not going to do it by turning and trying to seek what the media calls 'distancing....' " And, finally, borrowing a press-bashing line from Ronald Reagan, "I'm gonna take the case to the American people."

I'm gonna.. .I'd like to.. .1 have to— what's going on here? Why is this man, after twenty-two years in high-profile positions, forever rehearsing for leadership in public? He raps his own knuckles publicly: "But I will not project an arrogance—or overconfidence." He spills the beans about his strategy, publicly: "I'm going to be attempting to help [Dukakis] into the [liberal] mold, shoehorn him, help him in." He's up, he's down, he's giving us a play-by-play sportscast of his own campaign! Ailes, getting the feedback from such incontinent statements, says, "That's usually a signal that I have to get back to Washington."

Through all the ups and downs, George Bush appears to believe the real George Bush can't get elected. But insiders say he is utterly confident he would be a "helluva president." Jerry Weintraub says the desire is "burning within him." What drives the man?

Perhaps it is the fact that if and when George Bush, man of a thousand humiliations, gets to be president he will finally get to be like his father, like Ronald Reagan—the authoritarian leaders he has never dared to stand up to all his life. According to this view, held by some conservatives, Bush is the quintessential seething corporate vice president. He projects an image of "Good old George, kick him again, he'll take you back"—until the day he gets to run the whole show. And then watch heads roll.

Meanwhile, the vice president simply can't find the words to say what anyone who travels with him senses he would like to say: "Just give it to me, goddammit, I deserve it." What we see is Bush writhing through an identity confusion most late adolescents would recognize ("I must stand up to my father"). "I must define my political identity," he told the American public in mid-June.

By that time, waiting for James Baker had become an obsession with the Bush team. Atwater, Fuller, and Brady seemed to be yearning for Baker to fill the leadership vacuum; only Teeter, the current heavyweight, sounded mildly offended by the suggestion that the campaign was in disarray. The Godot figure, according to his boosters, has everything the Bush team lacks. James Baker has intellectual stature. He is a peer, but one who is top to bottom a politician. He is strong enough to say, flat out, "No." And he alone is willing to "force" the candidate to conform.

In early July, the Bush team was finally on an upswing again. Baker's long-anticipated arrival as campaign chairman was set for August. Meese was resigning. And the departure of Howard Baker, a Dole supporter, as Reagan's chief of staff opened the way for a Bush man, Kenneth Duberstein, to take the post. At last the Bush team had an advocate in the Oval Office. Duberstein had the authority to arrange a real working lunch with the president, at which Bush and his aides got Reagan to agree that Bush could disagree with him, "marginally," and that the White House would spring no policy surprises on the candidate. Finally, Reagan was bestirred to go out and stump for Bush among conservatives.

Suddenly, the attack scripts developed by Atwater to paint Dukakis as a left-wing McGovernite came alive. Reagan knows how to deliver them. But two weeks later, national polls still registered dreary results for the new strategy. The team's efforts to label Dukakis a sixties liberal had thus far failed. And although the negative campaign had made a dent in Dukakis's positive image among voters, neither Bush nor any of his surrogates had been able to improve the public's opinion of the vice president: only 26 percent of voters viewed Bush favorably.

And so, without ever asserting leadership or confronting the obstacles himself, but once again backed against a wall, Bush let his supporters fight his battles for him. Jim Baker, as Bush's éminence grise, is presumably the new authority figure in his life. The two men went off together for a "fishing trip" during the Democratic convention. But Baker knows what all the rest of them know in their heart of hearts. A candidate's advisers can prep him, protect him, cover for him, put quips on his tongue and a combat jacket over his suit. But, in the end, you can't change him.

Bismarck once remarked that "politics ruins the character." What may be missing in George Bush is enough strength of character to hold his own definition against all the chipping and filing, heavy sandpapering and polishing, that are inevitably part of what presidential campaigns try to do to shape their man's image. Most of the easy charm and grace of his youth is gone now. Jabs such as "Stand up!" "Be bolder!" "Go negative!" and "Cut loose from Reagan!"—meant to sharpen a man whose central character trait is die need to avoid controversy—may have bent Bush's carapace so far out of shape that he can't find the real George Bush anymore.

"All I know," says an old tennis buddy, Ham Richardson, who has known Bush for over twenty-five years, "is he isn't running as the real George Bush."

Indeed, the qualities his friends and supporters most value in Bush—nice, decent, easily senses what others want—are the same hallmarks of character that result in a lifelong pattern of mirroring and responding to others. The real George Bush's way is to adapt and adjust, not to form his reality around his own interests and convictions.

Under this premise, two serious questions must be raised about a Bush presidency. Who would really be pulling the strings behind the scenes? And how would a man who has such difficulty measuring out his own personal forcefulness—whether in directing his own team, dodging a TV interviewer, or standing up to Reagan—have the cool, when faced with a tense world situation, to chart a steady course between being too passive and "going ballistic"?

It is clear by now that George Bush is an outer-directed man. If he is able in the end to make voters comfortable with the fighting image his managers want him to project, perhaps at last the plucky lad from Yale will be comfortable with himself.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now