Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPLAYING FOR TIME

MARK MACNAMARA

Nearly every day, four serial killers on California's death row play bridge, but with both gubernatorial candidates pushing capital punishment, their games may be numbered

Letter from San Quentin

The serial killers play bridge from nine A.M. to one P.M. It's almost always the same four: Bittaker, Bonin, Clark, and Kraft. The game is in Yard 4, one of six yards for death-row inmates from East Block at San Quentin. Yard 4 is mainly for those who have trouble fitting in or who fear for their lives, the "walkalones," as they are called. "They're among the worst on the row," Clark told me once, "including the baby rapers and cop killers.*"

Yard 4 measures roughly twenty-five feet by forty feet, and holds up to forty men. There's a concrete wall on one side, and chain-link fence on the other three, topped by spirals of razor wire. In back of the wire, looking down from the gun rail, are three guards with semiautomatic Ruger mini-14s. There are free weights at one end of the yard, and a basketball hoop at the other. Between these on one side are a toilet behind a three-foot-high brick wall and, a few feet away, an unprotected shower. Across the yard from them is a square stainless-steel table with metal seats attached.

The bridge players use the table. Other inmates sit on the cement ground and play pinochle, dominoes, and Scrabble. Betting is not permitted, but it flourishes. Numbered cards are banned, so the bridge cards are handcrafted from pinochle decks. If the bridge players happen to have money, the game is for a penny a point. Partnerships are quite limited: Kraft and Bonin, who both killed young men and boys, loathe each other and won't play together. Bittaker and Clark, who killed young women and girls, are more flexible, but Bonin doesn't like to play with Clark, so the teams are usually Bittaker and Bonin, both of whom killed with an accomplice, against Clark and Kraft, who apparently always killed alone. Two other death-row inmates occasionally substitute.

Kraft is the most accomplished player of the four, and takes pride in his ability. Bonin is the least skilled player. Conversation at the table is usually sparse. Kraft, especially, keeps to his cards and resents distractions. He plays by the book and never tries to stretch his bid. He likes a peaceful, controlled game.

Clark is the opposite. He'll bid six hearts even if he suspects he and his can make only four. He onsiders himself an innovator, and is frequently thinking up new conventions, which are not always well received. He's also a jokester, who relishes psychological nuance, and from time to time he manipulates the game for his own amusement.

Bittaker enjoys the game's complexity, too, and will also experiment with unorthodox strategies. He peers over his cards, watching the other players carefully. Sometimes he loses patience with his partner, Bonin, and occasionally he may even sabotage a hand to show who's in control.

Bonin is the odd man out. The only one of the four who does not have an unusually high I.Q., he's often the butt of Clark's jokes, and he is treated disdainfully by Kraft and Bittaker. "Forget it," he will say angrily when he loses a hand, or after Clark has derided him for an inept bid. "That's ancient history. Forget the past."

These four men, who did not know one another before coming to San Quentin, were convicted of murdering a total of forty-nine people. If you add in uncharged victims and unverified claims, the number is probably closer to ninetysix. All the known victims were under thirty, and they were all white or Hispanic; most of them were killed in Los Angeles County. At one point, during the spring and summer of 1980, Bonin, Clark, and Kraft were all operating in the same area.

William Bonin killed fourteen young men and boys between August 1979 and June 1980. He dumped their bodies around Los Angeles and became known as the Freeway Killer. He's forty-three, squat, with dark features, a former truckdriver, and one of the most unpopular characters on death row—"truly evil," in the words of one inmate. He often proclaims his innocence, despite the testimony of three men who killed with him and the fact that he confessed to twenty-one murders in a vain attempt to avoid the death penalty by means of a plea bargain. He tells the other bridge players that one day his conviction will be reversed and he will write a book about his adventures and earn $5 million. With that, he says, he'll buy an island far away. He also speaks of the chance of a helicopter breakout to some country without extradition laws.

The sodium cyanide gas last billowed up out of the cast-iron bucket at the feet of cop killer Aaron Mitchell, who screamed that he was Jesus Christ.

Bonin committed his crimes at the same time as and within a few miles of Randy Kraft, who was convicted in 1989 of killing twenty-four young men. Kraft kept what prosecutors described as a "death list" of sixty-one victims. He was originally charged with thirty-seven murders and it is possible that he killed as many as sixty-three people.

The circumstances of two of Kraft's murders suggest that he had an accomplice, but none was ever charged. Almost all the murders were extremely violent. The victims were drugged and then tortured, and of the thirty-seven he was originally charged with killing, at least three were dismembered, seven were emasculated, four were burned, and one was strangled over a two-day period. Kraft probably killed his first victim in October 1971. Twelve years later, in May. 1983, he was stopped by police for driving erratically on the San Diego Freeway. On the seat next to him was a Marine, who had been drugged and strangled and who died a few minutes later.

Apparently, it was a sight to behold the day Kraft arrived on death row and Bonin saw him for the first time. "Like the student awaiting his master,'' said one inmate who witnessed the moment.

Kraft is slight, with strong features. He's handsome, but there's something ordinary about him. After graduating from Claremont Men's College, he was a computer consultant. In high school he had been a member of Students for Nixon. He reportedly has an I.Q. of 129. At his trial, he acted like a trim, unembarrassed bureaucrat accused of misusing government property. Kraft doesn't seem to fit the stereotype of the serial killer; he grew up in a middle-class household, apparently suffered no abuse as a child, and had no jail record prior to his arrest.

Lawrence Sigmund Bittaker is another matter. Larry Bittaker is fifty, wiry, with an extremely firm, cold handshake. He walks with an odd, floating stride, and has a triangular face with cat's eyes. On the row, his nickname is Dog, because he can sometimes be heard barking on the tier. He grew up with foster parents, spent much of his early life in prison, and in 1976 told a probation judge that if he were released he might kill people. Three years later he did.

In the late summer and early fall of 1979, Bittaker, then an auto upholsterer, committed five murders with a mentally disordered sex offender named Roy Norris, a man not unlike Bill Bonin. Together, Bittaker and Norris reportedly set out to kidnap, rape, torture, and kill a girl symbolizing each teenage year from thirteen through eighteen. Bittaker recorded the torture and screams of some of the victims on tape. He used pliers on one of the girls' nipples, and later signed autographs for fellow inmates on the row with the name "Pliers Bittaker."

Bittaker's closest friend on the row is Douglas Clark, with whom he enjoys a fragile relationship based principally on their resentment of and resistance to prison life. Clark is a good-looking man of forty-two, with strong blue eyes, a ready smile, and an easy manner. After seven years on the row, his face has the look of worn aluminum. Once known as the Sunset Strip Killer, Clark was convicted of murdering six prostitutes and runaways during the summer of 1980. The victims were all picked up on Sunset Boulevard. Most of them were shot in the head. One was beheaded.

Clark, who has steadfastly insisted on his innocence, was convicted largely on the testimony of a former mistress, a divorcee named Carol Bundy. Of the four serial killers who play bridge, Clark is the only one who has made a serious and sustained effort to get a new trial. He's an extremely angry man—angry at the prison, angry at the way his case has been handled, angry at himself. I've been visiting him for two years, and have often heard him rail bitterly at what he calls "the game," referring to the way the issue of the death penalty in California is played by the public, the politicians, the legal establishment, and the various advocates of defendants and victims.

From Yard 4 you can see the tall, skinny metal vent from the gas chamber. It has been twenty-three years since the last execution in California, when the sodium cyanide gas billowed up out of the cast-iron bucket at the feet of cop killer Aaron Mitchell, who screamed at the end that he was Jesus Christ. Once he was dead, the gas was drawn up into the vent and blown out over Marin County.

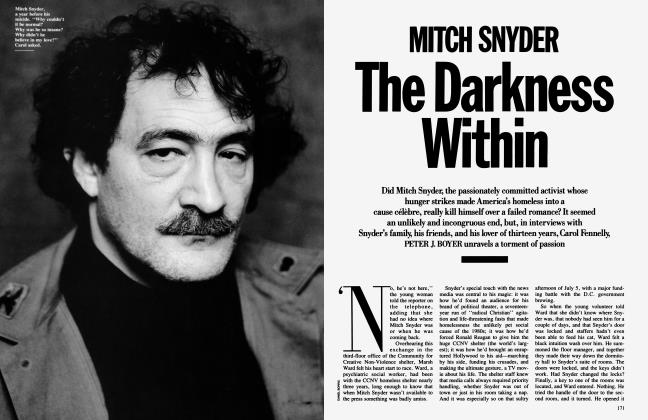

A man named Robert Alton Harris may be next. His execution, scheduled for last April 3, was stayed on the argument that crucial evidence had not been fully presented at his trial, but on August 29 the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the death sentence by a vote of 2 to 1. Harris's lawyers maintain that he suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome as well as from organic brain damage. His father reportedly kicked him even while he was in the womb, and began to beat him routinely by the age of two. However, in the opinion written for the appeals court by Judge Melvin Brunetti, the request for a new trial was denied because "allowing such battles of psychiatric opinions during successive challenges to the death penalty would place the Federal courts in a psycho-legal quagmire.''

Harris, along with his brother, kidnapped two teenage boys in San Diego in 1978 in order to steal their car for a bank robbery. They took the boys to a field and shot them to death. Harris's brother turned state's evidence, served three and a half years in prison, and got out. The tragic murder was made grotesque by a scene that was described many times in the press: one of the boys started to pray, but Harris derided him and killed him in the middle of his prayer. Afterward, Harris supposedly finished the boy's partly eaten hamburger.

"Deterrence was the argument in the early 1980s. Retribution is the argument of the nineties."

It's details like that that serve as the most passionate arguments for capital punishment, and since there were more than three thousand homicides in California alone last year, it's little wonder that the public can't get the executioner's song out of its head.

The politicians have heard it as well. In the Democratic primary for governor in June, Dianne Feinstein and Attorney General John Van de Kamp crawled over each other to plead their devotion to the death penalty, in spite of the fact that they had both been opposed to it in the past. And on the eve of the November election, the issue still bums bright, though Feinstein, who beat out Van de Kamp, and Senator Pete Wilson have no disagreement over it. Nevertheless, Wilson attacks Feinstein on what he says is her erratic position regarding the death penalty over the last twenty-five years. She counters that her thinking has merely evolved, that after a couple of personal experiences she sees the issue differently now. Both argue that the death penalty is a deterrent, though neither will say in what way. "I've seen too much in my life" is all Feinstein says to explain her altered position. "The police all say there is a deterrent value" is Wilson's argument.

But the real political argument for the death penalty in California is an 82 percent public-approval rating, according to a March 1990 Field Institute poll. That's the peak of an incline stretching all the way back to 1956, when just 49 percent were in favor. And yet the 82 percent is misleading, because when asked whether extenuating circumstances might make a difference in their approval, the majority shrank. In fact, when asked what the appropriate punishment was for a convicted person who had been seriously abused as a child, only 9 percent favored the death penalty; 41 percent favored life imprisonment without parole. Still, the public will is clear. "If the murder is especially brutal," according to the poll, 84 percent of the public tested was for dropping the pellets.

"Deterrence was the argument in the early 1980s," says Leigh Dingerson, director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. "Now that argument has been refuted by any number of studies, and what remains in this country is this sense that 'they deserve it.' Retribution is the argument of the nineties."

Perhaps Sharon Tate's mother, Doris Tate, describes the majority sentiment in California most accurately: "I really don't care if they're dead or alive, so long as they're kept in. But that's the problem. There's no guarantee. At least the death penalty keeps these people out of the way."

Ironically, Charles Manson, the man whose control over his followers seemed to symbolize the very essence of evil, avoided the death penalty. So did Sirhan Sirhan, who shot Robert Kennedy; Juan Corona, the notorious labor contractor who killed twenty-five migrant workers in 1970 and 1971; and the four Black Muslims who committed the fourteen "Zebra" killings in San Francisco in 1973 and 1974. All of these individuals escaped through legal windows of one sort or another, and all enjoy regular parole hearings, though it's unlikely that any of them will be let out of prison. But the possibility of that only increases the public's enormous frustration with the way the legal system has been administered in California over the past twenty years.

And that frustration has turned into a real hunger. Not to mention the practical problems involved in the system itself: There are 291 men on California's death row. Some estimates predict as many as six hundred by the year 2000. There's a sense that the number can't go on growing forever, and meanwhile trying and detaining murderers goes into the millions each year.

Since the death penalty was brought back into practice in 1977, sixteen states have executed a total of 139 people. There have been nineteen executions so far this year, and two more are scheduled for the near future. If those executions are performed, one more state, Wyoming, will have been added to the list of death-penalty states. There are now approximately 2,350 people on death row in this country, including some thirty women, although only one woman has been executed since 1977.

Given these statistics, the California public seems willing to pay any price to restore the death penalty. And yet there is a feeling that once a few killers have died, once the public finds that vicarious sense of being in control again, public compassion for criminals will return. "Now the idea is: Gas these guys," former governor Pat Brown told me. "But wait until you kill fifty. Then you'll see a reaction."

If anything changes the public will, it will be the perception not only that capital punishment is not a deterrent, but also that it has not been administered fairly. And that, ultimately, it may be impossible to administer fairly.

The appearance of fairness is significant. Of the 291 condemned men in California, approximately 35 percent are black, although blacks account for only 7.5 percent of the state's population. And there are only two women on death row, although numerous other women have committed murders every bit as brutal and premeditated as those committed by men on the row.

Of all the fairness issues, the question of insanity may become the practical undoing of the death penalty. "I have regrets about several of them," says Pat Brown, referring to the forty men executed during his time as governor. "The problem was that for some of them I couldn't get psychiatric evidence to support commutation on the basis of mental disability."

A doctor's testimony regarding sanity seems to be becoming the single most important factor in influencing a jury in capital cases. But many young public defenders don't understand this importance, or have no money to pay for a well-respected analyst. ''Also, you see a lot of doctors who don't want to get involved," says Dr. Donald Lunde, clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford Medical School. ''If you testify for the defense, there can be a lot of harassment, and you think, Why should I go through this? I'm being paid a pittance, people are questioning my competence—all this when I can do much better for society working in my office or in the hospital. The truth is that most competent physicians, psychiatrists, and neurologists just don't do this kind of work."

Dr. Lunde, who has examined many serial killers over the years, makes an interesting observation as to whether the death penalty serves as a deterrent: "The thing that few people know is that the death penalty has actually served as an incentive to commit murder." He cites the case of Edmund Kemper III, the sixfoot-nine, 280-pound giant who was released from a mental hospital after killing his grandparents when he was fifteen. He went on to murder six coeds in Santa Cruz—cut them up and ate parts of them. Eventually, he even killed his mother, decapitated her, tore out her larynx, and ground it up in a garbage disposal. Afterward he turned himself in to police. At his trial in 1973, he was found sane, but because the death penalty had not yet been reinstated, he was given a life sentence. "You know, one of Kemper's favorite fantasies in grade school was to die in the gas chamber," says Lunde. "At six, he and his sister played a game where he was strapped to a chair and had his sister pretend she was turning on the gas."

"Killing is kind of fun, like riding a roller-coaster." Carol Bundy even admitted she had played with the head of one of the victims.

The subject of the death penalty invariably leads to the question of whether an innocent man could be executed. The idea would seem absurd, considering the great sea of legalities to be crossed in every capital case, yet in a 1985 study of 350 death-penalty cases prosecuted between 1900 and 1984, researchers discovered that twenty-three men had been executed who were later found to have been innocent. Eight more who were innocent died in prison, and still another twenty-two had close calls, sometimes being reprieved only minutes before they were to die.

In 1989, Jerry Bigelow, who had spent eight years on San Quentin's death row and who had at one point asked to be put to death, won a new trial and was acquitted. The only other man to walk off California's death row was Choi Soo Lee, the subject of the film True Believer, whose murder conviction was overturned in 1983. "It's the 'politics of death' in California," says Bigelow's attorney, Robert R. Bryan, who recently secured a new trial for another man on the row. "We're the trendsetters in that respect. The fact is that those who wind up on death row here —or anywhere— aren't necessarily those who commit the worst crimes. The common denominator is that they're all poor. Add to that the uneven quality of public defenders, doctors, police, sometimes the political agenda in the county where the crime was committed, how much money the prosecution has to spend on a case, the judge, the makeup of the state supreme court in a given year—of course it's arbitrary, and little wonder that an innocent man could end up on death row."

Doug Clark, the bridge player known as the Sunset Strip Killer, may be such a man. He has been on death row for seven years, all the while claiming his innocence and working relentlessly to get a new trial. In fact, a number of technicalities in his case may lead to a new trial sometime early next year.

Clark's story is strange and convoluted. On August 11, 1980, Carol Bundy, a thirty-seven-year-old divorcee with two children, turned herself in to the Los Angeles police and confessed to the murder of her lover, an Australian named Jack Murray. She said one reason she had killed Murray was that she feared he might tell police about her other lover, Douglas Clark, who, she said, had killed more than fifty young women. Bundy told the police that they could find the murder weapons where Clark worked. Officers found two guns and arrested Clark.

Clark had been a boiler engineer in the San Fernando Valley. He spent his nights in country-and-westem bars picking up mostly overweight women, some of whom he wound up living with for a month or so. He occasionally went to swing clubs, hired prostitutes regularly, and satisfied his appetite for the erotic, and sometimes pornographic, as best he could. The one crime Clark admits to is having had sexual relations with an eleven-year-old girl. Carol Bundy, he says, was also involved.

By any standards, Clark is hardly an innocent. Nevertheless, there is compelling evidence to suggest that the murders he was convicted of may actually have been done by Carol Bundy and Jack Murray.

For starters, Bundy did not simply kill Jack Murray. She shot him twice in the head, stabbed him eleven times in the back, cut off part of his buttocks, and then cut off his head, to make it look like the work of "a psycho," as she said. She also gave the police details about the Clark murders that only the killer could have known, although she later insisted she had no direct knowledge of the killings. Yet, during her initial interrogation, she said that she had been involved in eight or nine of the murders. She even admitted that she had played with the head of one of the victims, Exxie Wilson.

At one point Carol Bundy told police, "Killing is kind of fun. It's like riding a roller-coaster." She also said, "If I was allowed to run loose, I'd probably do it again."

Clark was convicted almost completely on circumstantial evidence. The murder gun was in his possession, and a young woman identified his voice as that of the man who called her and admitted he was the killer. The police, however, did not offer the woman a selection of voices, only Clark's.

A prostitute who had been stabbed twenty-five times by a client also identified Clark, but only after having first identified another man. She was let out of prison in exchange for her testimony. Clark's lawyer was unable to discredit the woman's testimony, although recently a member of the woman's own family said, "She was always a wellknown liar. ' '

The really telling evidence against Clark was the testimony of Carol Bundy, specifically her accounts of what she said Clark had told her. But her statements were often conflicting, and she was rarely challenged. She claimed that she had been mesmerized sexually by Clark, for example, yet two years later, at his trial, she at first couldn't remember whether he was circumcised or not, and then guessed incorrectly.

Additionally, according to Clark, a piece of bloody blond scalp found in Jack Murray's van was linked to one of the victims, but that evidence was never introduced at the trial.

As for the trial itself, Clark represented himself during much of it and did an uneven job, to say the least. His main attorney, who would face misconduct charges in another case.two years later, admitted to being an alcoholic at the time of the trial.

Clark grew up the son of a naval officer. He traveled to more than thirty countries, went to private schools, and became worldly at a young age. There is no history of abuse, no record of any serious criminal offenses. Clark's only black mark seems to have been his unusual fascination with sex, though both of his wives and two other sexual partners all say he was never violent.

Jack Murray, on the other hand, had a reputation for violence. Carol Bundy has even admitted that Murray once threatened his little girl and her nine-year-old son with a gun.

Carol Bundy's own history closely resembles the pattern of abuse common among many serial killers. She has said that on the; day her mother died her father forced her to have oral sex. She was fourteen. She went from school to school, and by her own account had an extremely brutal childhood.

Both Clark and Bundy have recently agreed to take polygraph tests. But still, one wonders, why would Bundy want to frame Clark in the first place? She claims she has no animosity toward him, though she admits that the one thing she remembers about their relationship is that he endlessly humiliated her. If he ever does get out of prison, she told me recently, "he'll go to someplace else, some strange town, and after three or four years, if he settles in and is comfortable, he'll dig up some other perversion. More than likely, he'll not kill any more young women, but he'll find some other way to degrade and humiliate them.''

If executions are reactivated by California politicians in this election year, the issue has already been raised as to whether they can be televised. The local public-television station in San Francisco, KQED, has filed a petition in district court requesting permission to videotape an early execution. The station would like to replay the event, late at night, complete with a thorough explanation of both the crime and the punishment. The program would be followed by a discussion by advocates on both sides of the issue of the death penalty.

"We would not take a position pro or con," says director of news and current affairs Michael Schwarz. "Our sense is that this is a news event and an issue of major public-policy importance. And after all, this is the ultimate step: there's no greater act of authority on the part of the state, but the state is acting in our name, on our behalf, and with our money. Not to object is to let the government censor itself."

It's been an extremely controversial issue. The station has received hundreds of letters, overwhelmingly in opposition to the idea.

"Do it prime time," says Don Anthony, who spent ten years on Washington State's death row before being found innocent. "Tonight at nine. This is what you said you want. You watch it. Bring it to 'em. In living color. Don't be jivin'. Let 'em see how he chokes to death, or as he goes through whatever he goes through. Let them see it."

If you ask anyone on San Quentin's death row about the deterrent value of capital punishment, you are certain to hear the story of John Watson, the gunrail guard who made no secret of his interest in serial murders and who often visited the cells of the most notorious killers, including Bittaker, whose crimes were done in a silver van known as "Murder Mac."

On November 14, 1986, Watson offered a ride to a twenty-five-year-old prostitute, who claims she did not solicit him. Once she was in his van, he threatened her with a ten-inch knife and forced her to have sex with him. Later, as he was driving her to a secluded area, she escaped. Watson received six years, and with good behavior he could be out in three.

"The death penalty sure deterred him, didn't it?" says Douglas Clark with that shallow, ironic laugh he has.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now