Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE LOST PICTURE SHOW

Mixed Media

The BBC leads a holy-grail quest for the soul of showtown in a new series, Naked Hollywood

JAMES WOLCOTT

The West Coast writer Eve Babitz claims that merely to step outdoors in Los Angeles is to step into a movie. The light itself is cinematic, bright enough for impact, soft enough for flattery. It reigns like bliss. But there's barely a glimpse of Dodgerblue sky in Naked Hollywood, the five-part BBC series that begins July 28 on the Arts & Entertainment Network. The light is dimmed, tinted, diffused, mirrored, slatted, smogged, and shunted aside. Produced by Nicolas Kent and directed by Margy Kinmonth and Alan Lewens, Naked Hollywood inducts us into inside, indoor Hollywood.

The title, with its echo of Kenneth Anger's grave-robbing Hollywood Babylon, is a bit of a tease. Despite a lalapalooza opening shot of Daryl Hannah packed into a white dress, slowly exploding from the shadows to the boom of "Be My Baby," Naked Hollywood doesn't feed off celebrity flesh. With individual episodes examining the role of the director, the writer, the agent, the star, and the studio head, the series emphasizes not the eye-candy glamour of the movie business but the unseen grunt work—how light is cut into images which have become the world's stockpile of dreams. It's Hollywood as seen from the executive suite, screening room, and editing console—the anxious bowels of the biz. Its inquiry couldn't be better-timed. A blight has infected the Industry: profit margins are down, budgets have blown sky-high, and the quality curve has dropped off the graph. Nineteen fortyone gave us Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, and The Lady Eve. So far 1991 has graced us with Soapdish, Hudson Hawk, and What About Bob? The stockpile of dreams has become a toy box for mental defectives. What happened?

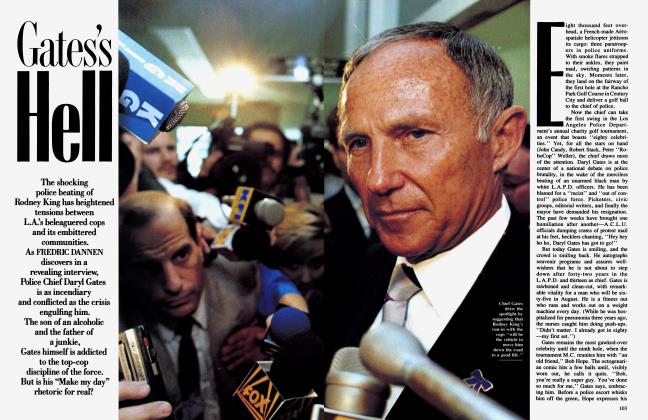

Naked Hollywood opens its investigation with "The Actor and the Star," a weigh-in pitting James Caan, in the white trunks, against Arnold Schwarzenegger. The show makes its sympathies plain. Schwarzenegger is first seen on a video monitor, Caan photographed in an austere white room. One is posturing illusion, the other prison-hard reality. Where Schwarzenegger began by stuffing himself into a bikini brief as a bodybuilder (bulging like a condom stuffed with walnuts, to steal a phrase), Caan was all balls as a son of Brando in The Godfather. Where Schwarzenegger schmoozes with the press, Caan hires a publicist to keep his name out of the papers. Where Schwarzenegger in his role as "Conan the Republican" leads exercises on the White House lawn, Caan shoots a few baskets by himself. Schwarzenegger: the joiner. Caan: the loner.

The moralizing point of "The Actor and the Star' ' is that flesh-and-blood refuseniks such as Caan have been paved over in the new Hollywood to make room for bionic constructs like the Terminator. But the makers of Naked Hollywood overdo the dichotomy. Much of the dip in Caan's career before he hit it big again in Misery was due to his own distractions. He spent too many of his wonder years at the Playboy Mansion (he even lived with a centerfold), and began pampering himself on-screen, phasing himself out from his fellow actors to practice his pained wince and mumbled aside. He egotized his technique until the combustion he showed as Sonny Corleone became a cozy fire. The interviews he gives in Naked Hollywood carry an oh-so-wry complacency. Schwarzenegger at least shows a sense of enterprise.

Where Naked Hollywood succeeds is in showing how the rise of Schwarzenegger is symptomatic of cinema's crazed steroid bloat. The entire industry seems to have gone Godzilla, too big now to get out of its own way as it tramples tiny multiplexes. Tons of time, money, and brainstorming are funneled into producing a simpleminded doodle a child would be ashamed to have in his coloring book. As evidence we see Schwarzenegger gearing up for Kindergarten Cop, directed by Ivan "the Terrible" Reitman, who brings in teams of writers to gang-bang the script. A cute idea at best becomes a blowhard sausage with beef by-products.

After Reitman's hack grin, it's almost a relief to come upon the humanistic fret of Sydney Pollack, who contends, "The films I make are very political—I think Tootsie was a very political film." His longtime collaboration with Robert Redford consists of more than hitching a wagon to a star—it reeks of myth. Redford is like America itself, says Pollack, a golden success with dark secrets. In an interesting coup, Naked Hollywood has Pollack dissecting a long, dialogueless scene from Havana in which Mr. America and Lena Olin cross the screen at different diagonals against a swarm of extras on a hugely expensive, elaborately reconstructed street. Pollack's play-by-play analysis is absorbing, but heavy hangs his brow. No wonder— more than $40 million at stake, Redford moving like a honeybee through molasses, and the memory of Casablanca looming overhead. If a lot of people don't go see Havana, admits Pollack, it'll be a major flop. And as we all know, Havana bombed from here to eternity. It's rather poignant in Naked Hollywood, this sense of impending doom. Like dinosaurs taking one last blink.

Mixed Media

The movie business is one of the few in recessionary America that still operate under an inflationary tail wind. (Sport is another.) Why are so-so talents showered with millions? Because, to paraphrase the director John Sayles, big boys don't want to jiggle small change. A huge flop at least has a certain hullabaloo. It spreads the waste around. Even so, there are limits. In an episode which unfortunately will not be shown on A&E,

Naked Hollywood covers the crash-and-bum of the production team of Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer.

After the success of Flashdance, Beverly Hills Cop, and Top Gun, Simpson-Bruckheimer blew a king's ransom on Days of Thunder, in which Tom Cruise dented his crash helmet in his peewee-Nietzschean pursuit of speed. {Top Car, some called it.) Not only was the movie a rushed mess, but Simpson and Bruckheimer built themselves a health spa with their own money and hired Hans and Franz to turn them into regular Schwarzenburgers. On the racetrack set of Days of Thunder, Simpson and Bruckheimer model tight black T-shirts and bun-hugging jeans as CHAOS swirls around them. As if that weren't spectacle enough, there's Simpson's frightening new beard, a failed attempt to disguise his jowly resemblance to Sam Kinison. (He looks like an evil twin's evil twin.)

Why isn't A&E able to broadcast this episode? Perhaps embarrassed by its days-of-blunder debacle with SimpsonBruckheimer, Paramount charged a stiff fee for use of footage from Top Gun and Days of Thunder. A pity, because the episode also tracks the efforts of producers Lynda Obst and Debra Hill to keep Terry Gilliam from running amok on the forthcoming Fisher King. They had good reason to guard the bottom line. Gilliam's previous film, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, burned a hole in its pocket to the tune of 48 million buckeroos. "The most expensive European movie ever made, Munchausen was a legendary disaster," writes Nicolas Kent in the spin-off book for Naked Hollywood. But Hollywood is a big believer in granting pardons. For The Fisher King, Gilliam was even allowed to shoot a sweeping waltz number in Grand Central Terminal. Economizing in Hollywood still leaves a lot of elbowroom.

For a brief flurry, inflation even hit the screen writing biz. Screenwriters love to talk of themselves as the farmhands of the Elm industry, peons bent in the fields as the fat bosses sit in the shade.

With devastating deadpan delivery, Penny Marshall describes hew she had the writers ef Big barred after one ef them spoke to the cinematographer.

But then big money began to drop. Shane Black's screenplay for The Last Boy Scout went for $1.75 million, topped by Joe Eszterhas's $3 million take for Basic Instinct. No wonder everyone I know is enlisting in Robert McKee's Story Structure class, hoping to get hit by lightning. My own blazing effort, You Call These Crabcakes?, is currently making the rounds of leading mailrooms. (Sure, I could change the title, but why should I compromise my VISION?) "Funny for Money," Naked Hollywood's salute to schmucks with typewriters, shows how low the screenwriter still sits on the traditional totem pole. Readers at the studios wade through constant slush. (In one amusing sequence, a script editor at Tri-Star demonstrates his "four-pillow system" for reading scripts in bed. One pillow goes under his head, another goes over his head to muffle outside sound, the other two allow him to turn pages without moving his arms.) Accepted scripts are rewritten at everyone's whim. The screenwriter is often a cootie on the set. With devastating deadpan delivery, Penny Marshall describes how she had the writers of Big barred after one of them spoke to the cinematographer—a major no-no. "You can't come around and play anymore," she told the writer. "You have to stay home."

But there are benefits to being out of the power loop. Compared with the methodical, harried execs we see parked behind aircraft-carrier desks in Naked Hollywood (Joe Roth, Ned Tanen, Barry Diller, Mike Medavoy, Tom Pollock, the ghost of Irving Thalberg), most of the writers seem relaxed and kibitzy. They don't have a Rolodex flipping behind their eyes. They watch The Simpsons together, gather at the Farmers Market for breakfast. Not having huge sums hanging over their heads, they can afford to flap their elbows and have fun. None of them are staring out to sea and contemplating the state of their artistic souls. "Am I a sellout? Am I? Am I?" Only Absence of Malice's Kurt Luedtke, pacing around with Sydney Pollack, seems caught up in the worry. Watching the two of them, you wonder how anything ever gets done. But then, that's the true mystery of Hollywood, that despite everything it actually functions.

Naked Hollywood uses clips from Mel Brooks's Silent Movie and passages from Sun Tzu's The Art of War to punch up its narrative. But the series missed an invaluable source for a close squint at Hollywood today. A few years ago Christopher Guest peered through his viewfinder at Hollywood disarray in The Big Picture, which starred Kevin Bacon as a fledgling director seduced and abandoned by musical-chair bigwigs. Sheepishly released, and rubbed out by the critics, this clever, underrated comedy covered the same topics as Naked Hollywood with true inside zip and a killer cast. As a studio chief, J. T. Walsh was a pair of panicky eyes set in sponge; Jennifer Jason Leigh cavorted in a rose-garden hat as a madcap Tama Janowitz type; and Martin Short hung it over the ledge as a fey, frazzled red-frizzed agent imploding with fabulosity. (His entire performance was a hilarious nicotine fit.) There was even a sexy parody of a sex fantasy, with Teri Hatcher straddling Bacon and purring a Dustbuster across his panting chest.

Made by outsiders, Naked Hollywood can't compete with Christopher Guest's dueling scars. Being television, it can only give us the small picture. But it has a studied surface, smart input, and beautiful night.shots of hills and haze that take you back to Raymond Chandler. Even when it's dark, L.A. gives great light.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now