Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowYears of Living Dangerously

Brandon Tartikoff's memoir raises the question, can he do it all again?

Tmorning after Labor Day, Brandon Tartikoff ushers a guest into his New York office and puts the best spin he can on Paramount's summer. "It could have been a disaster," he says. "And that didn't happen."

It seems a bit unfair to ask. The point of the interview is to publicize The Last Great Ride (Turtle Bay), Tartikoff's memoir of his decade as the wunderkind head of entertainment at NBC. But the book—which is, to give it its due, breezy and great fun—seems like an infomercial for Tartikoff the Paramount studio chief after a rocky first year. The message: I did it there; I'll do it here; just give me a little more time.

The parallels are unmistakable. In his first NBC year under Grant Tinker—his year, as he puts it, of living dangerously—Tartikoff battled Hodgkin's disease, came in to work every day while undergoing chemotherapy, and produced nine new shows. Record: 0-9. Still recuperating from a bad car crash in the summer of 1991 when he arrived at Paramount, he's had to deal with his nine-year-old daughter's far graver head injuries, spending weekends with her in New Orleans at a rehabilitation clinic, reading scripts on the plane. His Paramount stats? Somewhat better: for every All I Want for Christmas, he's managed to pull a Wayne's World or Addams Family out of the hat. But that's just the half of it.

Even last spring, agents were muttering about unreturned calls, producers about projects in permanent flux. Tartikoff was arrogant, they said; he didn't schmooze; he'd brought cheap TV tastes to moviemaking. Two major agencies were among those said to see Paramount as a last port of call. At NBC, Tartikoff learned from his mistakes and went on to brilliant success. Now, instead of cool, calm Tinker, he reports to Stanley Jaffe—a "pain giver," as one agent puts it—and ultimately to chairman Martin Davis, perhaps the toughest boss in America. Small wonder that rumors of Tartikoff's demise still hover in L.A. like smog.

Jaffe, for one, dismisses them. "That's typical Hollywood silliness," he scoffs. He and Tartikoff did spar, he acknowledges ("I'm a confrontational person"), and says Tartikoff had lessons to learn—No. 1 was how to run a whole company and not get mired in pet projects—but claims Tartikoff's "period of adjustment" is over. ICM's Jim Wiatt, among other agents, agrees Tartikoff is doing better. But some observers suggest Paramount faces a long winter before its strong slate of 1993 films (Adrian Lyne's Indecent Proposal; the thriller Sliver, with Sharon Stone; sequels to Wayne's World, Addams Family, and Beverly Hills Cop) hits theaters. Will shareholders wait?

They should feel cheered, at least, by Tartikoffs summer maneuvers. When Alec Baldwin dropped out of the $45 million Patriot Games six weeks before shooting, Tartikoff gambled $9 million on Harrison Ford to take his place; the star power helped bring in more than $80 million domestically. When Eddie Murphy's equally costly and nearly four-hour-long Boomerang bombed before focus groups, Tartikoff got involved. "One summer I worked as a movie usher," he says. "I'd see the same movie 20 times. Now if you asked me what movie I've seen most in my life I'd say Boomerang." Result: one hour and 50 minutes, and critical scorn, but $70 million at the box office.

Why Tartikoff failed to see that agents call more shots in movies than in television—well, he says, he sees it now. "I wouldn't say I'm going to work the town the way Tony Curtis did in Sweet Smell of Success. But I am going to try in a much clearer manner to let some of the key players in town know what Paramount is after."

In his book, Tartikoff recalls seeing Bill Cosby on Johnny Carson one night soon after his "dangerous year" and shaking his wife, Lilly, awake to tell her there was the answer. Cosby on family. . . a sitcom. . . reality-based. Wayne's World II may not prove a brainstorm of that caliber. But surely there's a little time yet. "In Naked Hollywood," Tartikoff says, "someone observes you're supposed to have 18 months to live. So I think I'm entitled to at least four more months."

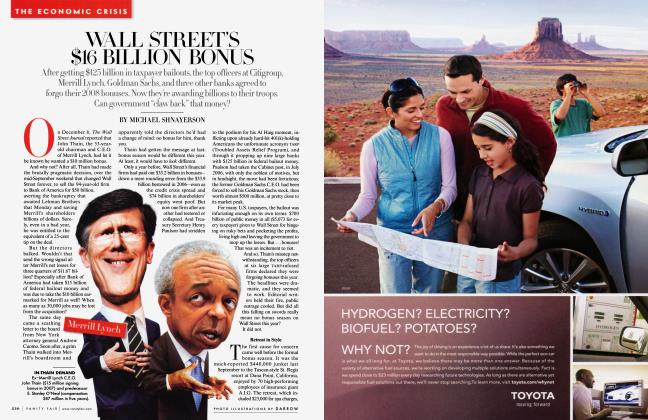

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now