Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCreating a Führer

How everyone bought the Hitler diaries

BOOKS

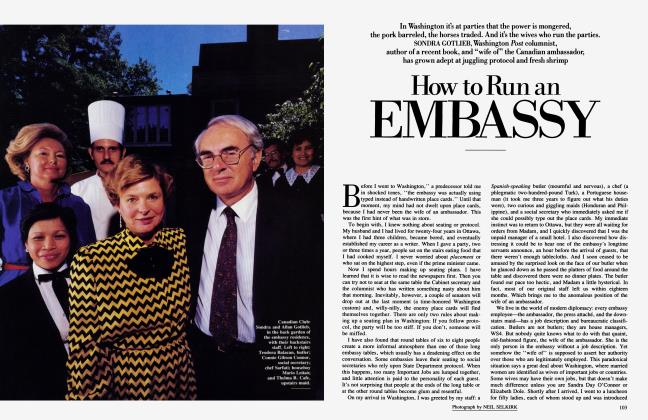

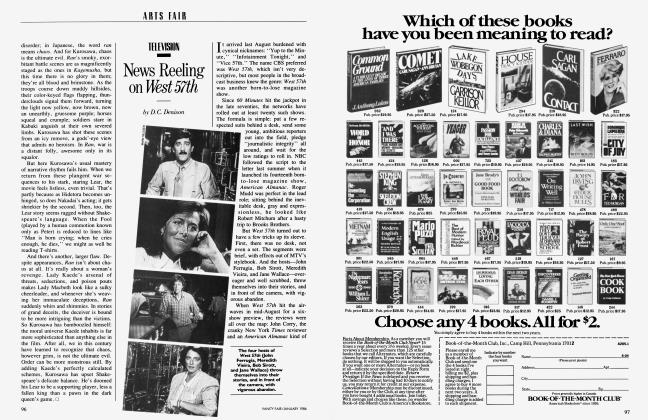

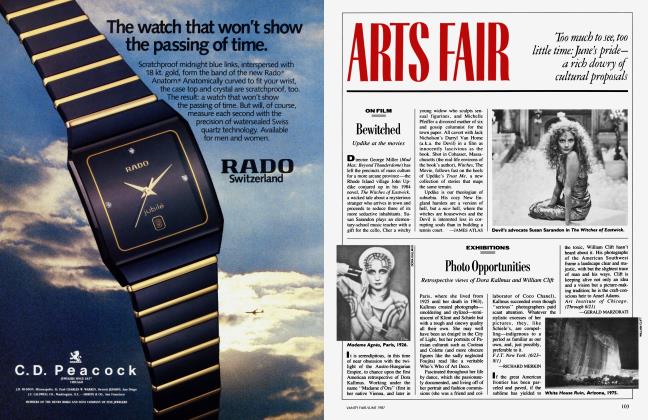

Born of a reporter’s obsession and nurtured by a forger’s deception, the Hitler diaries led them all on: clockwise from left, Gerhard Weinberg, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Gerd SchulteHillen, William Broyles, Peter Koch, Gerd Heidemann, Konrad Kujau, and Rupert Murdoch.

As diaries go, they were hardly hot stuff. No sexual antics. No dark nights of the soul. Most entries, in fact, were of tedious business transactions. But the diarist was Adolf Hitler, the business was the attempted conquest of the world, and the fifty-eight

black notebooks—nearly every page adorned with Hitler’s signature—struck the world in a two-day burst of headlined “exclusives” with only slightly less force than if the Fiihrer himself had risen from the grave. Two weeks later, the spectacular scoop of the century collapsed: the diaries were proved fakes.

How had three of the world’s largest

publishing companies—Stern magazine’s Gmner 4Jahr, Rupert Murdoch’s News International, and Katharine Graham’s Newsweek, Inc.—committed such a gaffe? The tale, as told in Robert Harris’s admirably researched Selling Hitler (Pantheon), is part corporate folly, part comic opera.

It starts with the monomania of a shy Stern reporter named Gerd Heidemann, whose collection of Nazi memorabilia included Hermann Goring’s table service and goblets. Upon learning of a “Hitler diary,” Heidemann dogged its trail to a relics store in Stuttgart and a proprietor who gave his name as Conny Fischer.

What humble forger could have spumed the entreaties of such an obvious patsy? Not Fischer, a.k.a. Konrad Kujau, who told Heidemann that his brother, a general in the East German army, had secured a whole cache of diaries when a transport plane carrying them from Berlin

at the war’s end went down near the German town of Boemersdorf. The crash was a proven, if little-known, fact; the diaries seemed to fit right in. For two million marks (about $1 million) and a promise of anonymity, Kujau agreed to have his brother smuggle them one by one across the Berlin wall in lorryloads of pianos. Heidemann took the news not to his

disdainful editor, Peter Koch, but to Gmner + Jahr’s top management. Soon, as Harris points out, the players were involved in three layers of mendacity: Kujau’s deception; Heidemann’s own deception of the forger in skimming from two years’ worth of cash payments; and Gmner + Jahr’s decision to keep the secret from Stern’s editors.

All that followed now made a dizzy sort of sense. To keep from endangering the “East German general,” Gruner + Jahr could bring in no outside experts until it had the diaries in hand. When Gmner + Jahr’s managerial director, Gerd Schulte-Hillen, finally made the decision to publish and quietly sell worldwide rights, historians Gerhard Weinberg (representing Newsweek) and Hugh Trevor-Roper (representing Murdoch) had time only for snap judgments based, in part, on the word of handwriting analysts whose own comparison studies were thrown off by phony reference samples.

Harris’s account, flecked with dry wit, draws telling portraits of checkbook journalists. Murdoch comes off as a tough but rather admirable negotiator. William Broyles, the golden boy whose short tenure as editor in chief of Newsweek would be dealt a fatal blow, seems at best an opportunist. When negotiations for American rights fizzled, he and managing editor Maynard Parker went home to publish pirated excerpts as news, concluding their accompanying cover story about the diaries with a hedge that “genuine or not, it almost doesn’t matter in the end.”

Sad lessons were learned when simple laboratory dating tests were finally conducted. Hoaxers, it turns out, have as easy a time as they do because the hoaxed so want to believe. Assumptions, in every case, betray the assumer; one of the silliest was that the diaries‘must be genuine because they were so dull. As for the cowboys of checkbook journalism, they had to learn that the practice erodes not just ethics but a fundamental tool of the trade—skepticism. That leaves them dangerously vulnerable, as profit rather than truth becomes the motive. Only Murdoch seems to have understood this and made his grim peace with it. “Circulation went up and it stayed up,” he said of the London Sunday Times. “We didn’t lose money or anything like that.”

Michael Shnayerson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now