Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

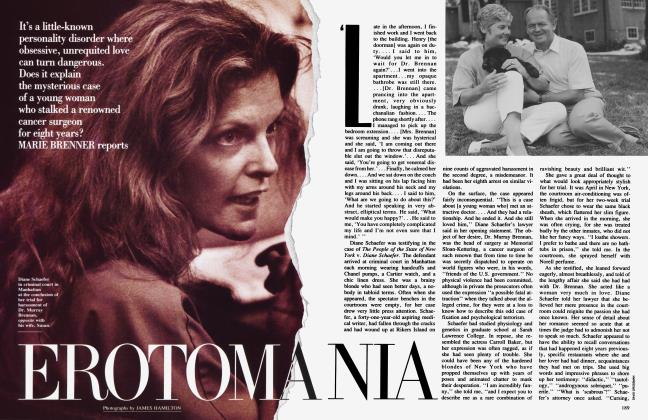

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMad About Helen

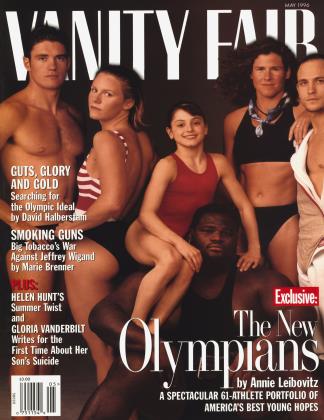

Helen Hunt has achieved a stealth stardom as the attractively loopy Jamie Buchman on the TV hit Mad About You. DAVID KAMP gets a dose of Hunt's quirky charms as she goes big-screen big-time with the lead female role in Twister; Jan De Bont's explosive blockbuster follow-up to Speed

DAVID KAMP

'Reading hundreds of potential 'Hers' and 'About Men' columns each week," announced The New York Times Magazine on January 21, "editors found increasing repetition: toys for boys, sharing a motel room, resentment of parents. Meanwhile, many writers have offered affecting and instructive stories in which gender is not the fulcrum. Consolidating 'Hers' and 'About Men' into [a new column called] 'Lives' opens the way for such stories."

For Helen Hunt, it was a date that will live in infamy. "I'm so mortified by it that I cannot describe it," she says. "There's something so comforting about reading ..." A pause, and a smirk at the words to follow: " . . . genderspecific stories. I lived for the 'Hers' column every Saturday night, when my Sunday New York Times would come. I think what they've done is the most malicious thing, and I can't believe it's gone!"

Well, you offer, trying to soothe, at least they've got that new, non-gender-specific thing called "Lives."

"I hate it! Can I just say I hate it? I should be writing them a letter. I hate it so much!"

It comes to light that Hunt and the Times Magazine have a bit of a history: specifically, she submitted her own potential "Hers" column for publication a year and a half ago, and the editors told her it needed work. "They said it was two separate pieces—write one or the other. But it didn't feel that way to me. It's two stories converging to say one thing. I felt like they were kind of right and kind of wrong, and I couldn't find my way to doing it the way they wanted me to do it." So no revisions were ever exchanged, and the piece never ran. Out of this tale of missed opportunity comes, strangely, a reassuring thought: Helen Hunt really is like that. Animatedly decrying the demise of a favorite column, candidly hashing out the details of a pet project that didn't come off, waiting with bated breath on Saturday night for the arrival of the Sunday Times—these are precisely the sorts of things that Jamie Buchman, Hunt's character on the NBC sitcom Mad About You, might do.

Mad About You, now winding up its fourth season, is a quiet hit, neither the merchandising juggernaut that is Friends nor the quotable warhorse that is Seinfeld; it has its little patch, which it works with aplomb. Pauline Kael once wrote of Louis Malle's Murmur of the Heart, "This is perhaps the first time on film that anyone has shown us the bourgeoisie enjoying its privileges." So it is with Hunt's show, an anomalous (for TV) look at a happy upper-middleclass marriage, less relentlessly fretful than thirtysomething, less rose-tinted and didactic than The Cosby Show, and miles away from the Weltschmerz of Ingmar Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage, which, if memory serves, at one point has Erland Josephson kicking Liv Ullmann's head in. Jamie Buchman is a publicist, her husband, Paul (Paul Reiser, who is one of the show's creators), is a documentary filmmaker, and they live with their big, agreeable dog in an enormous apartment on lower Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. They stay in, they dine out, they read in bed, they make love, they occasionally get on each other's nerves, and, above all, they prefer each other's company to anyone else's. It's all so cozy, without being saccharine, that Mad About You evokes an even greater desire than usual to hear that the actors are really as friendly and sharp as the characters they play. You want to know that Helen Hunt is Jamie Buchman, and even though this turns out not to be the case—for starters, the former displays an erudition and seriousness not readily apparent in the latter— it's nice to discover that there are similarities enough: the self-deprecating sense of humor; the serene demeanor occasionally punctured by surprising, contagious bouts of loopiness; the scrubbed, unfussy presentation of a woman who likes looking pretty but is a little past trying to look cool. It's nice to learn that even in real life Hunt has fallen for a funnyman (her steady boyfriend is Hank Azaria from The Birdcage and The Simpsons) and that she spends every Thanksgiving with her friend Anthony Edwards, ER's saintly Dr. Mark Greene, about whom she says—further happy confluence of fiction and reality—"Tony's a menschy guy. He totally is. He's just what you think."

Odd, then, for Hunt to be turning up, of all places, in the starring role of what promises to be this summer's biggest zillion-dollar, explosion-laden blockbuster: Twister, Jan De Bont's follow-up to his 1994 hit, Speed. Sandra Bullock's turn behind the wheel in the earlier film marked the beginning of her continuing reign as America's favorite ordinary-seeming famous woman, and the current Hollywood wisdom has Hunt, as the latest of De Bont's leading ladies, about to become similarly huge. (Typical industry thinking: It's a trend—it's happened once before!) Up to this point Hunt's feature-film roles have tended toward the urban, talky, and professional: she has been the whippersnapper agent to Billy Crystal's elderly comedian in Mr. Saturday Night and, more notably, the conflicted book editor who ministers to her extramarital lover, a paralyzed writer played by Eric Stoltz, in Neal Jimenez's astonishingly good independent film, The Waterdance. Twister, produced by Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment company, represents something of a departure. As its title suggests, the film looses De Bont's gift for kinetic mayhem on the subject of tornadoes. Hunt and Bill Paxton play Jo and Bill Harding, an estranged scientist couple who specialize in monitoring and chasing tornadoes in the rural Midwest. Michael Crichton's screenplay pulls a deft gender reversal, positing Jo as the fierce, determined obsessive with a difficult past and Bill as the flummoxed, sensible spouse who, against his better judgment, sticks with his gung-ho partner.

(Continued on page 217)

"She's been working nonstop since she was a kid, and kept her head above the madness."

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

(Continued from page 168)

"I keep reading these articles, and everyone, from Arnold Schwarzenegger to my mom, is doing an action movie and saying, 'But this one's really about characters,"' Hunt says, eyes rolling. "But, having said that, I think this movie has much more character development than any other action movie I've seen or heard about. They really wrote a woman's part—in a big, huge, fat action movie—that's complicated."

Come to think of it, Bullock was no simpering ninny in Speed; De Bont, improbably for a former disciple of Showgirls director Paul Verhoeven, is emerging as a champion of women. "I had to fight with the studio to get Sandra, and 1 had to do the same for Helen," he says. "I like strong women, and I like to work with actors who don't feel like they have to be the same person in every movie."

Hunt fulfills the order—and does it with passion. As the "Hers"-column episode suggests, she is interested primarily in stories where, as the Times Magazine might put it, gender is the fulcrum. "I have a 17year-old cousin I'm very close to," she offers, "and I'm gonna give the speech at graduation. An all-girls school—I like that it's all women. Somehow the fact that it's women makes me feel like I've walked in those shoes, so maybe there's something I can say that's inspiring or comforting or confusing or something."

Over and over again, she brings up her desire to tell women's stories. Example: last year, by virtue of her immense popularity on Mad About You, Hunt was offered several book deals, among them one of those face-on-the-cover jobs that get synopsized in the best-seller charts as "Anecdotes, observations, and meditations from the television actor." Given the current book market, taking on such a project can be as lucrative as getting a movie lead: Reiser's first book, Couplehood, was a No. 1 best-seller in both hardcover and paperback, and the rights to his second book, about his new parenthood, recently fetched a reported $5 million advance from William Morrow. Hunt asked one of the editors she met if, in the event she consented to do a book, she could do something different, maybe 15 essays about her experiences as a woman. Like 15 "Hers" columns? "I can tell you for sure it wouldn't have to do with me being an actress or famous, but more to do with the women who came before me, like my grandmother and her mother, and my 17-year-old cousin, and why Meryl Streep is called 'over 40' instead of 'an actress.'" (The editor was receptive, but Hunt has decided to postpone the literary career.)

At 32, Hunt is representative of a generation of moderately famous actors who have been in the business for at least half their lifetimes, registering success in steady dividends rather than mammoth payoffs. Tim Robbins, Eric Stoltz, Anthony Edwards, Mare Winningham, Helen Slater: they're neither besieged superstars nor used-up John Hughes refugees. "I'm a slow-and-steady-wins-the-race sort of person," Hunt says, "and I get nervous when anything moves too quickly."

"People don't realize that Helen's the hardest-working gal in showbiz," says Stoltz, who first teamed up with Hunt in 1989, in a Lincoln Center production of Thornton Wilder's Our Town, and has since made guest appearances on Mad About You. "She's been working nonstop since she was a kid, and kept her head above the madness."

Indeed, given Hunt's curriculum vitae, her unshakable sanity practically warrants inclusion in Ripley's. Her father, Gordon Hunt, is a director and acting coach whose work kept the family toggling back and forth between the East and West Coasts throughout Helen's childhood. She began acting professionally at age nine, first playing the she-towhead in things like Swiss Family Robinson and The Mary Tyler Moore Show (in the latter she was Murray's daughter), then moving on to movie-of-the-week piffle ("I was a princess from outer space once [in a 1976 episode of The Bionic Woman]. I had these square-toed silver boots and a little lame outfit, and I gave this deep, like, Sophie's Choice monologue about my people back home"), then spending a lonely lateteens sojourn in New York taking dance lessons, then returning to L.A. for further adventures on the soundstages, then back to New York in her early 20s, then back to L.A. yet again. She could easily be an awful, jaded, seen-it-all showbiz casualty in thrall to firearms, rhinoplasty, and Lady Blow. Why isn't she?

"She's always had this remarkable sense of balance," says her father. "She had a savvy about her as a teen that you would equate with that of someone in the business 20 years," says Anthony Edwards, who first met Hunt in 1981, when they were cast as brother and sister in a failed sitcom called It Takes Two. "I remember meeting her and thinking, She looks like she's 17, but she's going to take care of me."

Indeed, talking to her actor friends, you get the sense that Hunt is the rock of her group, the stalwart who keeps it all together, socially and mentally, for everyone else. Edwards says their Thanksgiving tradition arose 14 years ago when his parents had just divorced and she thought to invite him along to her friends' house in Connecticut. Slater, Hunt's best friend, tells of meeting her husband at an improv class to which Hunt had dragged her, and of going once a year with Hunt to Hawaii, where, sans their men, they "live like nuns, not talking to each other all day, just reading books and meditating." Stoltz is positively rapturous as he recalls the moment Hunt first cast her spell on him. He'd known her fleetingly, having been Edwards's college roommate at the time of It Takes Two. One night, "as I was driving home on the freeway she pulled up next to me, and we locked eyes and drove side by side and flirted for quite some time. For some reason, that moment always stayed with me—it sounds ridiculous, but some strange, hopeful connection happened that day."

Hunt has kept her head about her, it seems, by being a PBS-tote-bag kind of girl, immersed in literature, high culture, and worthy causes. Her house, in the unglamorous Valley, is the occasional converging site for a group of actors— Azaria, Slater, and Mad About You's John Pankow among them—who devote their Sunday nights to the most earnest of exercises in actorly betterment, the informal Shakespeare workshop, wherein plays are spiritedly read aloud and BBC videotapes of the Royal Shakespeare Company are dutifully scrutinized. Her musical tastes run to opera, James Taylor, Joan Osborne, and "the earlier, totally earthycrunchy" Joni Mitchell. Her nightstand is stacked high with chunky, interesting books that, because she can talk the talk, you can tell she's actually read: Wallace Stegner's Angle of Repose, Gabriel Garcia Marquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude, Anne Lamott's Operating Instructions. "There's a whole group of Northern California writers—Annie Lamott, Armistead Maupin, Ethan Canin—who I love," she says. "They all mention each other in their books. I just want to fly up there and go 'Can I be in your club?' "

But before you assign her too many Berkeley-Berkshire correctness points, before you get her completely stuffed into that tote bag, she pre-empts any presumptions of sanctimony with that same endearing wryness she's assigned Jamie. O.K., she's pulling for Clinton this year, she's all for Ted Danson's save-the-oceans campaign, so what does she think of Joan Didion's line from The White Album about liberal Hollywood's being "a dictatorship of good intentions . . . devoid of irony"?

"'Devoid of irony'? Jesus, she's so brutal! [Expansive laugh.] All right, we'll all just go . . . fuck ourselves!"

This talent for nimble self-effacement has helped turn her into a relaxed, confident actress with a particular gift for nuance. There's a wonderful offhandedness to the way Jamie Buchman bustles half dressed through her apartment as she prepares for work, countervailing her husband's assertion that khakis are the same thing as chinos by muttering, "Myth, myth, myth: one is a color, one is a style"—all the while never bothering to break her stride, or even lift up her head. She's so real you can touch her. Even Reiser gets caught up in the cognitive confusion. "We have that shorthand way of speaking that real married couples have," he says. "Some days we'll be between scenes in rehearsal and I'll say, 'Can I get you a cup of coffee, honey— er, uh, I mean, Helen?' "

With Hunt, this kind of confusion is quite easy to understand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now