Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

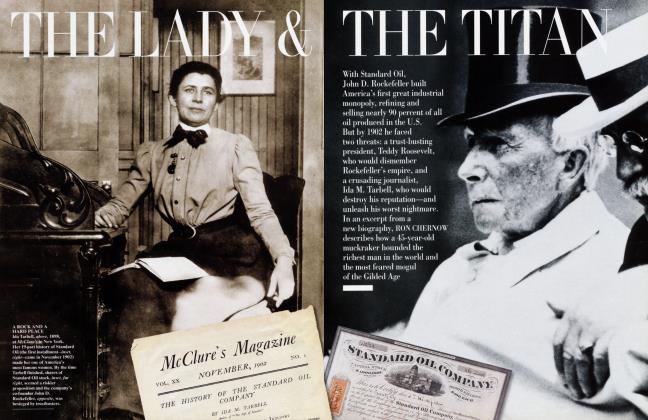

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SHOCK HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

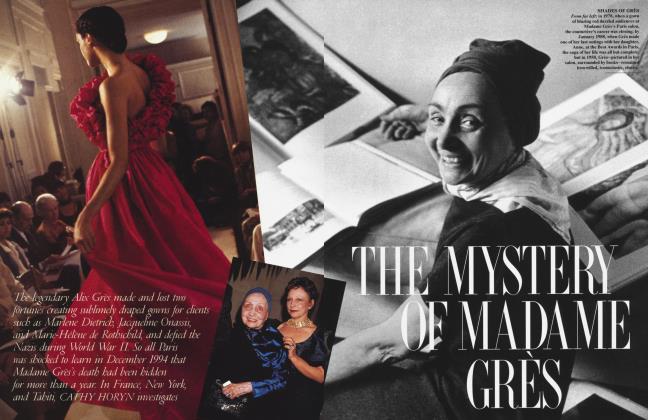

Fashion

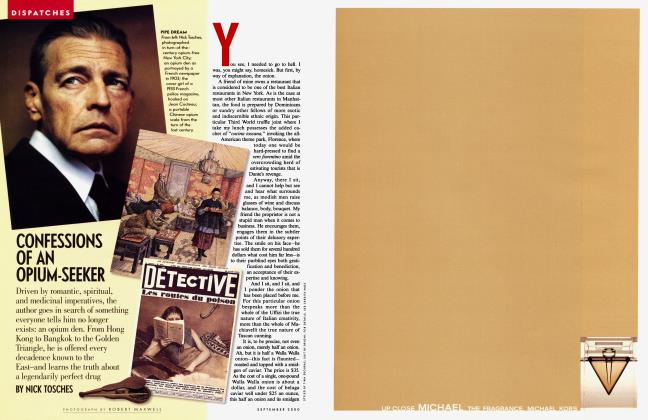

Thirty years ago, fashion rebel Rudi Gernreich outraged a more innocent America with his topless bathing suit, unisex jumpsuits, thongs, and see-through tops and bras. Today he's being honored as a pioneer by the Metropolitan Museum's Costume Institute and echoed by top designers from Tom Ford and Isaac Mizrahi to Donna Karan

CATHY HORYN

In the early spring of 1985, like a ghost from the grave, Rudi Gernreich, the sly genius behind the H topless bathing suit, commandeered the spotlight one last time.

Two decades earlier, this serene and soft-spoken man of 42, a Viennese Jew who favored silk cravats and toupees that looked blown on by Chester Gould, had been the first bona fide fashion guru to come out of the California youth culture of the 60s. To imagine the uproar that his most notorious innovation produced, you have only to think of the headlines, the moral indignation, all those censor-barred photos of giddy young women being escorted from public beaches by grim-faced policemen. Everyone wanted to crucify Gernreich. The Vatican, the Kremlin, the governments of Denmark and Greece—not to mention the Carroll Avenue Baptist Mission of Dallas—all denounced him.

Yet no designer came closer to evoking the era's new freedoms, or to ventilating high fashion with more pure fun. Gernreich was one of a kind, a singular cross between an old-world radical and a space-age aesthete, with a dash of Barnum thrown in. Not for nothing was his daring black brief, with its straps rising graphically, but superfluously, through the cleavage, eventually enclosed in an Italian time capsule between the Bible and the pill.

By 1985, however, the old rebel was in the last stages of lung cancer. There was nothing doctors could do for a man of 62 who had smoked his first cigarette at age 6, and who was known as much for his inexpensive Sherman Cigarettellos as for his polished American voice. (Everyone mentions the smoothness of that voice, which rarely betrayed his Continental birth.)

CONTINUED ON PAGE 125

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 122

Gernreich—who pronounced it rick, not rike—always swung without a net. He had arrived in this country in 1938, six months after the German occupation of Vienna, with nothing going for him but his uninhibited imagination. By the early 50s he had laid out an almost perfect vision of the future: sex, style, fun, color, freedom. Gernreich's farsighted clothes—ultralight tube dresses, unlined bathing suits, the screaming three-tone checkerboard pants that Lauren Bacall wore for Life magazine in 1953—summed up everything that was about to become exciting. It was like looking through the pinhole of one of those scenic souvenir charms and seeing the entire Manhattan skyline spread out before you. Except that it was the 60s and the little guy in the center, the ringleader, was wearing trousers of wild houndstooth. And that cravat.

He was a sartorial advance man with clairvoyant tendencies. And guts: no fashion innovator ever put himself so willingly on the road to ruin to liberate a few square inches of flesh. In 1967, at the peak of his cockeyed career, when he had dressed no less than Barbra Streisand and was on the cover of Time, Gernreich's business, including knitwear and other products, was grossing around $1 million. But by 1970, when he had embarked on a new concept called unisex—featuring, in the scheme, a couple both fully nude and freshly shaved—his numbers had plummeted to $67,000. They would never rise.

Today, no disasters stem from showing a model in a see-through top, but that is largely because Rudi Gernreich had the nerve to do it first. Despite that, there are those who regard his contributions as nothing more than the gross antics of a born huckster. Yet there is probably not a garment of the last 35 years which has meant more to women than Gernreich's 1965 invention, the first completely soft, "no bra" bra. It literally changed fashion's shape.

Gernreich himself was nothing like his swingy clothes. The great irony of his life was that, for all his outrageousness as a designer, he lived for more than 30 years in the same house, with the same man, Oreste Pucciani, a distinguished U.C.L.A. professor of French. Their cozy-eccentric cottage in Laurel Canyon mixed modern art, leather Eames and Breuer chairs, and, most curious of all, an elevated reflecting pool designed by the Russian photographer George Hoyningen-Huene to take your mind off the vertiginous view. Every night after work Gernreich would climb into his 1964 white Bentley and drive back up the hill to the Eameses and the Breuers and the reflected California sky. His was a mind that needed no distraction at all.

Rudi Gernreich began his final design project in the spring of 1985. Though he was sick and broke and had spent the previous few years making soups (he thought there was a future in prepared gourmet foods), he completely immersed himself in the work. In March he announced to his old friend photographer Helmut Newton that, with his newest design— the so-called pubikini—he had succeeded in "totally freeing the human body." You had to see the pubikini to believe it. The thing was nothing more than a couple of thin strips of black stretch fabric sewn together—a lewd thong, if that's possible. Layne Nielson, who worked with Gernreich in the 60s, remembers that unless the tiny triangle was pulled and pinned in a particular way it looked "just like a pair of Lili St. Cyr underwear."

"Rudi was a bullyboy with the press," says model Leon Bing, "in the same category as Capote and Warhol."

The pubikini, with its naughty peek of pubic hair, was plainly for publicity, but with Gernreich nothing was ever that simple. On the day that Newton came to the house in Laurel Canyon to photograph the creation, Gernreich took a grease pencil and outlined a triangle on the model's exposed patch of hair. Then he had the spot dyed a sinful shade of green. It was his final act of subversion.

A month later, on April 21, the last American fashion rebel of the 20th century was dead and gone.

Thirty years after his impudent heyday, Gernreich belongs more than ever to contemporary fashion. Although he himself is practically forgotten, his influence is everywhere—from see-through clothes and clashing colors to porthole cutouts and hard-edged minimalism. Even those Yfront briefs that women like so much:

Gernreich. He did them seven years before Calvin Klein, as former Los Angeles Times fashion editor Marylou Luther has pointed out. (Luther's interviews with Gernreich remain a primary source for his public utterances.) To the new generation, Gernreich is the undisputed soothsayer.

"He's an unsung hero of the avant-garde. Rudi was always ahead of his time."

"He's an unsung hero of the avantgarde," says Jeremy Scott, a rising star in Paris, who recently turned down a top design job at Versace. "Rudi was always ahead of his time." For those who need

more positive proof of Gernreich's enduring influence, Layne Nielson keeps a file of current clippings that show, line for unmistakable line, the designers—Isaac Mizrahi, Tom Ford, Donna Karan— who have dipped into Rudi's well. It's a thick file.

Gernreich—who will receive his due this month, when the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York features his work in a retrospective called "American Ingenuity"—was not the only provocateur in American fashion. But he was the first to see the big picture, to triangulate fashion, culture, and politics and use clothing as a kind of exquisite sociological message board of the here and now. As Gernreich pointed out in 1971, "It's important to say something that is not confined to its medium."

In a way, Gernreich was too bright for a calling as strewn with sacred relics as dressmaking. He didn't know the first thing about setting a sleeve, and the times he offended some Seventh Avenue panjandrum with his unconventional methods are legion. (Norman Norell got his Indiana knickers in a famous twist when Gernreich won the Coty Award in 1963. After returning his Hall of Fame Coty in protest, Norell told Women's Wear Daily, "I saw a photograph of a suit of Rudi's and one lapel of the jacket was a shawl and the other was notched -Welir)

But we know which way things went. Says Vidal Sassoon, the London hairdresser who matched Gernreich cut for cloth all during the 60s, "In retrospect, if you look at what was happening then, it was really like being involved with a metamorphosis, a total breakthrough. In essence, the cut of cloth and hair was developed in the 60s and has remained standard for many young designers. Rudi had so much to do with that from an influential point of view."

Gernreich would have been tickled to see his ideas running around again on fresh legs. He loved being the center of attention, and had, it appeared, an unlimited capacity to absorb the coos and contretemps of a notorious public life. "He basked in it," says Nielson, who remembers times in the designer's Los Angeles studio—at 8460 Santa Monica Boulevard—when all hell would be breaking loose and Gernreich, under a cloud of Cigarettello smoke, would be calmly expounding his theories on nudity to a reporter 3,000 miles away. "He was a bullyboy with the press," says Leon Bing, a star Gernreich model, "in the same category as Capote and Warhol. He used the shit out of something that would eat you alive."

In another sense, however, Gernreich would have been horrified at becoming an inspiration for copycats. His mind was set awhir by the new, his imagination spiked with wit. (Example: when June Newton, the photographer known as Alice Springs, was looking for a nom de lens with an Australian ring, Gernreich suggested "Dawn Under.") "Rudi really wanted to be avant-garde," says Peggy Moffitt, his most sensationallooking model who still, at age 60, is a visual jolt of white Pan-Cake and 60s gear. "That was all he cared about . . . being first."

"I felt I had to be experimental at any cost," said Gernreich, "and that meant always being on the verge of a success or a flop."

Gernreich surrounded himself with l-a progressive young California artists, 11 such as Ed Ruscha and Larry Bell, with whom he made a 1970 underground movie called Crackers (Gernreich played a night porter in the sexy farce), and an eclectic crowd that included Carol Channing as well as Brooke Hayward and her then-husband, Dennis Hopper. He supported causes— without showy, red-ribboned pretension—and in the early 50s helped found the first radical gay-rights organization, the Mattachine Society.

"I think that he lived in an eternal present," says Oreste Pucciani, Gernreich's companion of 31 years, as we sit one day in the walled garden of their Laurel Canyon home. Perhaps because Pucciani is of two minds about the value of vintage Breuer chairs versus the comfort of his five beloved dogs, the modern hillside house isn't the showplace it was when water hyacinths floated in Gernreich's cosmic, superfantastic reflecting pool.

But this does not mean that Pucciani has forgotten anything. At 82, he is not only that most improbable of figures, the Sexy Older Gentleman—with a full head of hair, a film star's visage, and most of his marbles—but also a reporter's dream. Laying out the details of his extraordinary life with Gernreich, beginning with the night they first met, Pucciani omits none of the exciting parts. ("I put my hands around him and kissed him on the mouth . . . ")

"Well," the old don says with a merry skip in his voice, "it was love at first sight. Bang-bang7" up to a lot of heavy weather. He dwelled neither on his father's suicide in 1930 nor on the Nazi occupation in 1938, which forced him and his mother to ernreich, who was s I-born in 1922, didn't £ U put a lot of emphasis on his Vienna childhood, probably because the facts added leave their books and seaside trips to become y refugees in a shabby little L.A. apartment. Still, Vienna influenced Gernreich's avant-garde style. For one thing, his family was socialist, and—as Stuart Timmons, who catalogued Gernreich's papers for U.C.L.A., points out—socialism teaches you to think in terms of historical patterns; in other words, the big picture. Second, Gernreich was constantly drawing as a kid, street scenes and so forth, images he would later use. For example, Bacall's three-tone checkerboard pants were almost certainly inspired by the grid-like cubes of the Bauhaus. And the topless swimsuit was similar to a children's bathing brief worn on Danube beaches in the 30s. Even the bare-bottomed thong of 1974 came from a Vienna image. Gernreich told Leon Bing that this daring apparatus was based on his seeing, at the age of four or five, workmen in tight leather chaps with straps running straight up their backsides.

So Gernreich arrived in California with a mind open like a big rolling lawn. But nothing came easy. His first job, in the morgue at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, was preparing cadavers for autopsy. His real love was modern dance, and by the mid-40s he was training with choreographer Lester Horton and supplementing that career with income from fabric design.

One cannot overstate just how handsome he was, especially in those days. "Beautiful," says Pucciani. And not only did he possess full lips, high cheekbones, and a lithe, muscular body, he had an allure that was specifically sexual. "He was one of those people you look at and know they like to do it," says Bing.

What tends to deflate all this is that for years, beginning in the 40s, Gernreich wore a toupee. One just doesn't associate a guy like Gernreich with a piece of goods as flagrantly unhip as a rug. Yet the need for this conventional cover-up reveals "a delicious chink in the armor," as Bing says. There was a sensitivity to Gernreich and maybe a little insecurity. He used to tell model Jimmy Mitchell, when she'd drive up in her Ferrari, "Let's go in my car. I don't want to blow my hair."

By 1950 he had taken a job in New York with George Carmel, a coatand-suit firm. Gernreich's ideal was Claire McCardell, the Seventh Avenue design maverick who had eliminated linings and darts and whose models looked naturally sexy, as if they had just come from tennis at Vassar. Gernreich wanted to make the same sort of waves. But bigger. And higher. Yet, after six months of having most of his designs rejected because they didn't fit into the French mode, he was dismissed. Back in California, he joined an outfit called Morris Nagel Versatogs ("a schlock house with a name to match," he was fond of saying), and generated novel ideas until he felt he had to leave that job as well.

"I knew it could ruin my career," said Gernreich of the topless suit. "Fear of being pre-empted led me to say okay."

What finally put Gernreich's designs over was Jax, a store in Beverly Hills. Jax was a mecca of inspired retailing, a total scene, and when Gernreich began selling clothes there, in 1952, it was as if some giant fissure had opened up and all the conventional types, all the Georges and Morrises of the worldwell, who cared about them? Gernreich's simple cotton dresses sold out in about an hour.

The clothes—loose and comfortable, with pockets for keys and lipstick— weren't actually all that shocking. But by the late 50s, when Gernreich started hiking hemlines before anyone else and introducing colors that looked wildhues such as magenta and orange—you could see where he was going. Says Brooke Hayward, daughter of producer Leland Hayward and actress Margaret Sullavan, "My father used to say it was really unattractive to see a woman's knees, and in a way he was right. But Rudi went right along because he was interested in youth."

What Gernreich seemed to comprehend was something that almost nobody in a business obsessed with "the right sleeve" could have possibly been alert to. Namely, that for every dame who bought the line about "the glories of the French couture," there were probably 50 California teenagers running around in stretch pants, listening to Elvis Presley records.

Gernreich wasn't the only designer to see what millions of postwar teenagers would mean to fashion. Emilio Pucci in Italy and Mary Quant in London were also on the ball. But none of them, no matter how far you stretch the lines, could match Gernreich for sheer audacity. The man was not just brilliant, he was utterly unfazed by the terror that causes so many designers to compromise and hand over the reins to marketeers and assistants. Gernreich always designed alone. The one backer he had, Walter Bass, who had financed his rise, was, by 1960, a former associate. On his own, Gernreich would build an enormous business, with every kind of product deal—about 15 in all—from bodywear to bedspreads. And he would lose them all; he would sacrifice the financial security he'd gained, as well as his notoriety, because he would never make the slightest artistic compromise.

It was insane, even tragic. But don't think that Rudi Gernreich ever saw it that way. As he said in 1968, when he left his business at the height of his fame to go sit in a castle in Morocco, "I felt I had to be experimental at any cost, and that meant always being on the verge of a success or a flop."

The risks Gernreich took at work were supported by a rich private life, which rose up around him like a garden wall. Before Pucciani, he had had several romantic unions, including a reported affair with James Whale, the British-born director of Frankenstein. In 1950 he had become infatuated with Harry Hay, a left-wing activist who drafted a kind of manifesto for gay rights. "It's the most dangerous thing I've ever read," the designer told Hay, "and I'm with you 100 percent." The lovers formed the Mattachine Society, with Gernreich enlisting support from friends in the film colony, including Katharine Hepburn's favorite director, George Cukor.

Gernreich's relationship with Pucciani, which began in 1954, was more complex. "Their mutual attraction was palpable on all levels," says Bing. "They were so wonderfully paired—intellectually, emotionally, and sexually. They were hot for each other."

The two met at a party at the Laurel Canyon house, with Pucciani immediately taking the younger man aside and inviting him back for supper the next evening. "And that started it all," says Pucciani. "It was a perfect marriage, I would say."

Pucciani was a brilliant academic who, in addition to advancing a standard method of teaching French, had a long friendship with Simone de Beauvoir. "There are very few people who can pull the whole thing together intellectually, and Oreste could do that," says Patricia Faure, an L.A. art dealer. The couple's home, with its cerebral blend of books and Bauhaus furnishings, was the scene of many lively dinners—"the most interesting in Los Angeles," says Sassoon—yet it was clear who ruled the roost. "Oreste was very much the last word in this," says Bing. "If he didn't like someone, they weren't welcomed." Another friend adds, "It was a gay relationship, and a modern one. They had an emotional fidelity that wasn't always a physical one."

The two never discussed money. According to Bing, Pucciani didn't even carry it with him. "We never had any discussion of that sort," he tells me with a shrug. "We just never had it. We could afford this house and this type of living. We were both very independent people."

In the 60s, Gernreich's career exploded. He was doing things so far ahead of everyone else, like inserting clear vinyl panels in swimsuits and extending the graphic pattern on clothes to matching shoes and tights—what he called the Total Look—that he seemed in a class by himself. "You have to realize nobody was doing stuff like that," says journalist Priscilla Tucker.

"Rudi had to capture everyone he came into contact with."

Carol Channing had begun to wear his clothes—causing a huge flap in 1967 when the chiffon puffball dress Gernreich gave her for Lynda Johnson's White House wedding accidentally rode above her thighs while she was foxtrotting with the secretary of state. Despite the hullabaloo ("Lady Bird was on my side"), Channing remained devoted to Gernreich. "The reason I wore his clothes—and that was all I wore—was that he had a sense of humor," she says.

Curiously, except for Channing and a few other stars, such as Barbara Bain, Gernreich didn't pursue the Hollywood crowd. "Rudi couldn't have cared less about that," says Hayward. "He was interested in dressing people like Peggy Moffitt, who had a certain attitude." Both Hayward and Channing, who were frequent guests at Gernreich's, noticed the contrast between his exuberant clothes and his low-key lifestyle. "It was interesting, truly," observes Hayward. "He lived up there on that hill and it was a very genteel life."

Because of his attention-getting clothes and outgoing charm, Gernreich became a personality. "He always knew the right things to say," remembers Luther. "He had to capture everyone he came into contact with," says Nielson. He did this with editors by filling their ears with an edifying mix of prediction and pop sociology. You can imagine the effect this had on reporters who had literally spent careers waiting for dressmakers such as Madame Gres to utter so much as a usable sentence. "Eugenia Sheppard [of the New York Herald Tribune] made very, very sure that Rudi got a lot of ink," says Tucker. So, when the man in the spotlight predicted, in 1962, that "bosoms will be uncovered in five years," the press was all for it. And the fact that Emilio Pucci had made a similar prediction only fed their sense of journalistic thrill. Suddenly it was like the moon race, except with boobs.

After the topless came out, in June 1964, and Gernreich's name was all over the papers, Pucciani made the comment that once a garment becomes front-page news it ceases to be about fashion. Gernreich must have decided he liked being a pundit, because after that he started pouring on his hip theories. "He was on the phone most of the day," says Nielson. It was ironic, though. Until Look magazine approached him in 1963 about doing a topless bathing suit for an article about futuristic fashion, Gernreich wasn't thinking seriously about sexual taboos. He didn't even approve of public nudity, not at that point, and would have happily never sold one suit (much less 3,000) if Vogue's Diana Vreeland hadn't talked him into producing it. Because the only reason Gernreich did the damn thing was ... to beat Pucci.

"I knew it could ruin my career," he admitted later, "but my conviction that it was right and my fear of being preempted by someone else led me to say okay."

As Gernreich knew, there were no grown-up words that could have soothed that childish ego. At any cost, he said. Though he was hailed by Time in 1967 as America's most influential designer, it was another story behind the scenes. "Rudi refused to face the reality of the manufacturing business," says Nielson, recalling creative piques that ended in broken contracts.

Gernreich believed that his final design-the pubikini —had succeeded in "totally freeing the human body."

"Even with his own line, it was like pulling teeth. The woman who ran the workroom would scream at him, 'Rudi, you have to give me something to produce!' " It was almost as if he was too busy predicting the future to design clothes. On top of that, he started telling people that fashion was dead. Today that would be no big deal, but in 1968, it was like spitting in church—the church being Women's Wear Daily, which snubbed Gernreich. "All he achieved by that," says Nielson, "was making sure his own fashion was dead."

After taking a year off, Gernreich returned to fashion, but somehow the momentum wasn't there. He was productive, still farsighted, but he was preaching a gospel of comfort and anonymity to a world that wasn't yet converted. A man who always gave more than he received, who never let his thinking get fenced in by convention, Gernreich spent his last years making soups, delivering them in his Bentley. He kept his disillusionments to himself, spoke often of Vienna, and died like an artist, owing money to at least one friend—the $1,000 he needed to complete his final design statement, the pubikini.

All his life Gernreich looked to the future. In the early 70s, when the rest of the fashion set was obsessed with hemlines, he was trying to create a dress without using a needle or thread—a new garment molded entirely from synthetics. It was a flop, but he had this nutty idea that there was a future in high-tech fabrics. If he didn't have anything leftno empire, no pot of gold—it is simply because his mind was too expansive for those things. As Pucciani told me, "I don't think he worried about what would remain after he went."

So it was surprising to learn while I was in California that Peggy Moffitt (the model most associated with Gernreich and the topless design) and her husband, photographer William Claxton, had acquired, unbeknownst to Pucciani, the trademark to Gernreich's name. Moffitt told me their plan was to find investors and reproduce Gernreich's designs under a label that would include her name. "Very few people really know him now, but they do know me," she explained. "They know my name and they know my visage ... In fact, I said to the trademark office that my physical ity is representative of Rudi in the way that Mickey Mouse represents Walt Disney."

The whole thing struck me as utterly preposterous, and when I brought it up with Pucciani, he replied by saying something in French that roughly means "Up yours" and calling an attorney.

Better as a final memory is the story that Jimmy Mitchell tells. It was 1948 or '49, and the lanky blonde was in a department store in Los Angeles when this young man zigzagged up to her and said, in a perfectly dreamy American voice, "Pardon me, but I'm going to be a designer and I want to build all my clothes around you. You're exactly the vision I have in mind." But exactly. The guy had some nerve, didn't he?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now