Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

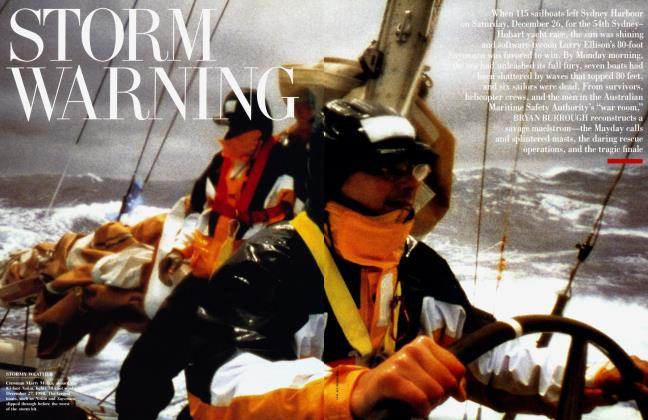

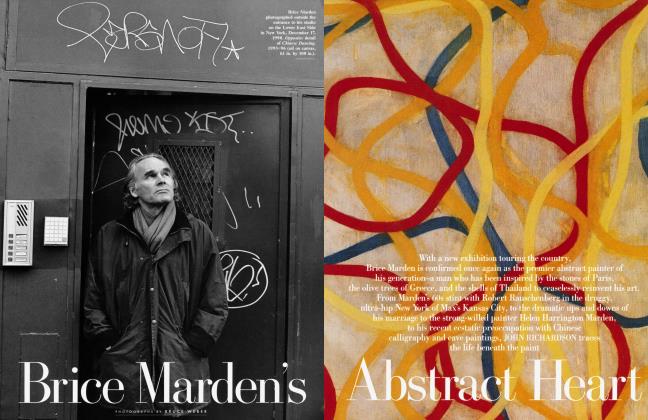

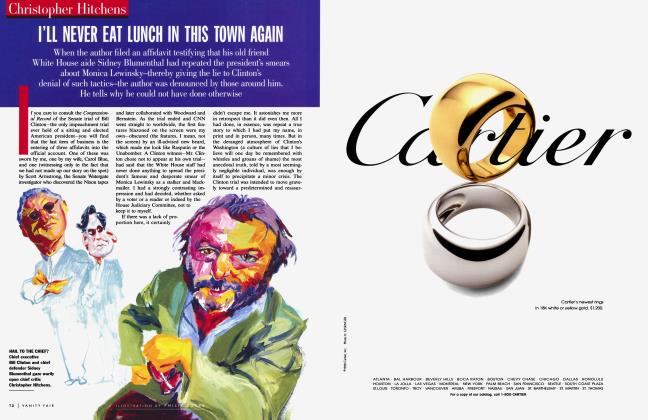

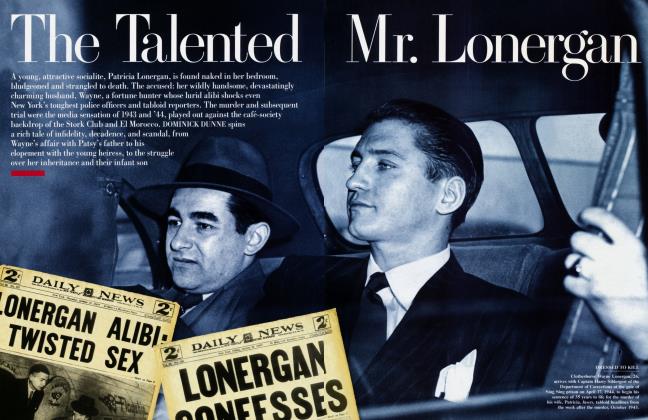

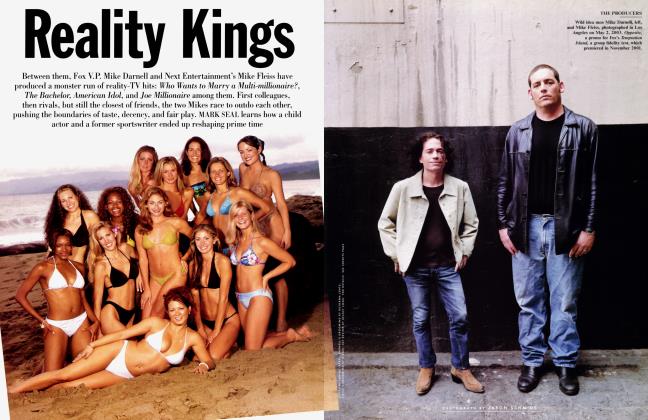

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWashington was not a city DOMINICK DUNNE knew well, but in covering President Clinton's impeachment trial he stepped into a drama worthy of his own fiction. From the end of his friendship with Lucianne Goldberg—who in 1997 had told him the first stories about a White House intern—through a round of Georgetown dinner parties, to the gallery of the U.S. Senate, Dunne finds echoes of scandals past (Martha Moxley, William Kennedy Smith, O. J. Simpson) in the scandal that trumped them all, and finally loses his faith in the president he once idealized

May 1999 Dominick Dunne RiskoWashington was not a city DOMINICK DUNNE knew well, but in covering President Clinton's impeachment trial he stepped into a drama worthy of his own fiction. From the end of his friendship with Lucianne Goldberg—who in 1997 had told him the first stories about a White House intern—through a round of Georgetown dinner parties, to the gallery of the U.S. Senate, Dunne finds echoes of scandals past (Martha Moxley, William Kennedy Smith, O. J. Simpson) in the scandal that trumped them all, and finally loses his faith in the president he once idealized

May 1999 Dominick Dunne RiskoPolitics has never been my main topic of conversation, and Washington was a city I scarcely knew when I arrived there in early January to attend the impeachment trial of President William Jefferson Clinton. I was seated in the periodical gallery of the United States Senate, looking down on 100 senators as the House managers, led by Henry Hyde, presented their case against the president. Heady stuff, watching history. My feelings were passionate, at that point, and my devotion to Bill Clinton was absolute. Unlike Christopher Hitchens, another writer for this magazine, who publicly despises Clinton, I was an ardent admirer of both the president and the First Lady. I felt a personal dedication to them that I refused to allow anyone to tamper with.

I admit that a lot of my ardor had to do with star power, a subject that has always fascinated me. Although I have never had a conversation with the president, I have several times been up close at hotel-ballroom events where he was an electrifying presence, the greatest I've ever seen, and I have been in rooms where Jack Kennedy electrified. I started to like him on the 60 Minutes segment where he denied that he had had an affair with Gennifer Flowers. I was impressed that he could withstand that kind of personal exposure on TV and not fall apart. I was at the Democratic convention in Madison Square Garden in 1992, waving a flag and cheering during his acceptance speech. I was in a hotel room in Berlin when I watched Clinton's oration at the funeral of Yitzhak Rabin in Israel, and I wept at the beauty of it. I was in a hotel room in St. Petersburg last June when he gave his first great speech in China, and he filled me with feelings of patriotism, which happens to be a great feeling that we don't get often enough. As for Mrs. Clinton, I've had two conversations with her. The first was in 1992, at a dinner party in the apartment of Alice Mason, a noted New York hostess, where Norman Mailer sat next to her for the first two courses and I got moved into the chair for dessert. We talked the whole time about Chelsea, who was then 12, and I could feel the love she had for her daughter. The other time was in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York two years ago. I was stunned that she remembered me and the conversation we had had. She complimented me on the articles I had written about the O. J. Simpson trial. Let me tell you, getting a compliment from the First Lady also happens to be a great feeling. I have always looked on the Clintons as two larger-than-life characters in a novel that I would just love to write.

Over the past year, when people who had felt as I did about the president began to lose faith in him, I remained stalwart. I knew, but I didn't want to know. Moreover, my dislike of Linda Tripp and Ken Starr was so extreme that it increased my loyalty to him. I also came to dislike Henry Hyde and his dour, rightwing band of House managers, and the idea that any of them could bring him down filled me with loathing.

The sex scandal had held me captive from the beginning—even before the beginning, as a matter of fact, for I had had an insider's access all during the initial stages, when I was privy on a daily basis to the latest steps in the manipulation and betrayal of Monica Lewinsky by Linda Tripp, as stage-managed by Lucianne Goldberg, who used to be a friend of mine. But I'll get to that.

A large portion of the Democratic establishment in Washington had lost all respect for the president.

For the first few days in Washington, until I got my bearings, I was steered around by Dee Dee Myers, a Vanity Fair associate, who had been a White House press secretary under Clinton. She left in 1994, torn between affection and disappointment regarding the man she had served, and she was currently a regular television commentator on the Lewinsky affair, primarily for Larry King Live. Dee Dee knew everyone and saw to it that I met the people I needed to get to know in the capital. "This is Gwen Ifill of NBC News," she'd say. Or "The blonde woman at that table is Senate minority leader Tom Daschle's wife. She's a lobbyist." Or "This is John Czwartacki. He's Trent Lott's press secretary, and he gives a briefing for the media nearly every day." Out of Czwartacki's hearing, she said, "The girls call him Dreamboat."

Dee Dee arranged for us to have lunch with California Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein in a Senate dining room. Feinstein felt strongly that the president should be punished but not removed from office. In the weeks to come, she would sponsor a resolution to censure the president, but it would be derailed by Republican senator Phil Gramm.

"Would you like to have dinner with Jamie Rubin of the State Department?" Dee Dee asked. "He's Madeleine Albright's assistant, and he's married to Christiane Amanpour of CNN." Sure, I said. We ordered ostrich, at Jamie's suggestion. Right from the start, I had a good time.

During the day, there was always someone to look at in the visitors' gallery, and I was pretty good at pointing them out: There are Whoopi Goldberg and Frank Langella ... There are the Kennedy sisters, and the one with them in red is Teddy's wife, Victoria ... That's Senator Byrd's grandson ... That pretty blonde lady is Patricia Duff, who was recently divorced from Ronald Perelman and is going out with Senator Torricelli of New Jersey.

After two days, Dee Dee went back to California, where she lives, and I was on my own.

Being at the State of the Union speech was a thrilling experience. The spectacle of the justices of the Supreme Court walking in, followed the Cabinet, led by Madeleine Albright in turquoise and Janet Reno in purple, was American pageantry at its best. Usually, for the State of the Union speech, First Ladies wear bright colors for the television cameras, but this year Mrs. Clinton appeared in black, which I thought made a statement about her mood. All that day her husband's impeachment trial had been going on in the Senate, and it would be going on again the next day. As she acknowledged the thunderous standing ovation she received when she entered the gallery, her demeanor was that of a gracious lady whose husband was in big trouble. She sat with civil-rights legend Rosa Parks and baseball hero Sammy Sosa, and before the speech started she chatted and laughed and appeared to be having a wonderful time, but I felt restraint rather than joy coming from her.

The president's entrance—greeting this one, reaching out, laughing, giving a special hello to Democratic representative Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas, who had been so loyal to him in the House hearings—was great theater. He was his usual electrifying self, as if he didn't have a care in the world, although he knew perfectly well that there were many in that chamber who hated his guts and wanted to remove him from office. The president's speech was great, and he delivered it wonderfully, never mentioning his personal crisis. No one enjoyed the speech more than Representative Patrick Kennedy of Rhode Island, Senator Ted Kennedy's son, who was time and again the first person on his feet to lead the standing ovations, like an old-time politician.

It was commendable of the president to acknowledge Hillary's accomplishments, but he should have stopped his tribute there. Instead he went on and mouthed "I love you" to her for the camera, which, considering that his adultery had brought on his trial, came out as spin rather than homage or love. Nevertheless, that evening of January 19 was a triumphant one for the Clintons.

I was struck by the courtesy of the majority of Republican senators and House members, who had the manners to stand and applaud the presidency, even though they thoroughly disapproved of the president. There were exceptions, the prime one being Majority Whip Tom DeLay of Texas, who had steered the House away from voting on censure, as the Democrats wanted. Avoiding rising, looking like the C.E.O. of a small-time pest-control company, which he used to be, he smirked and appeared supercilious throughout the speech. One week later, The New Republic resurrected allegations that he had lied under oath concerning his role and responsibility when he was still at the pest-control company.

If you have a proclivity for going out every night, as I have, a cocktail party hosted by Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn to launch Erik Tarloff's entertaining book, FaceTime, about a presidential speechwriter who finds out that his girlfriend is having an affair with the president, was the ideal place to be the night after the State of the Union speech. Ben Bradlee is the retired executive editor of The Washington Post, and his wife is a writer, hostess, and social force in the city. I've known Sally Quinn since the 70s, before she married Bradlee. It's interesting to watch someone you knew early on become a person of consequence, and Sally was one of those people you could always tell were going to be somebody. Never leaving the center of the hallway, she greeted guests as they arrived, introduced those who didn't know one another, and said good-bye to people as they left, often with a knowing laugh or a confidential whisper or a proposal to get together, as only an expert hostess knows how to do. In November 1998, she had written a very controversial article in The Washington Post about the relationship between the Washington establishment and President Clinton, and she had taken a lot of heat for it. What I was to find out during the five weeks of the trial was that her article was very accurate. A large portion of the Democratic establishment had lost all respect for the president. Its members did not want to see Clinton removed from office. They wanted him to resign and turn the office over to Vice President Gore, who is part of the Washington establishment and always has been.

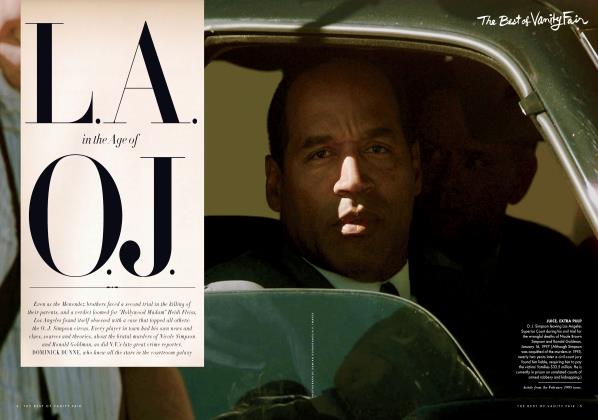

Luckily I was acquainted with a number of the players on the D.C. scene, and most nights there were interesting dinners in Georgetown houses and restaurants. The conversation never wandered far from the impeachment trial. I was reminded of Bel Air dinner parties during the O. J. Simpson trial, when people talked of nothing but that trial for the better part of two years. Out there I had been a participant in the conversation, because I was familiar with the terrain, but in Georgetown I just listened, because it was all new to me. A couple of nights I found myself at the same party with one or two of the three witnesses whose depositions were about to be shown on videotape at the trial, both of whom I knew. "I can't talk about it," they would say, but then we'd talk around it. Sidney Blumenthal invited me to the White House for a peek at the Oval Office when the president wasn't going to be there. Vernon Jordan seemed unconcerned with the ordeal ahead of him, even though his appearance before the House managers was only a week away. "We're not going to talk about it," he said, setting the rules for the evening's conversation, and we didn't, but he joked about wearing a white suit and spats to the deposition.

From the beginning, there was virtually no chance that the president would be removed from office. People said that if there had been a secret ballot—as there used to be at the Doges' Palace in Venice—the outcome might have been different. Certainly there were Democratic senators who wanted the president to remove himself from office and make way for the vice president, but nothing in the House managers' arguments was ever likely to change a single Democrat's vote. Except for Asa Hutchinson, the Republican from Arkansas—who shares a Virginia apartment with his brother, Senator Tim Hutchinson of Arkansas—the managers turned out to be not a very effective team, and certainly no match for the superb team of lawyers representing the president. A reporter I know, who had turned against Clinton, whispered to me in the gallery one day, "The guy doesn't deserve such good lawyers as these."

The House managers kept trying to shock the Senate with the constant repetition of a story that had long since lost its shock value. The TV-talk-show hosts and comedians had seen to that. Most of the managers couldn't keep their self-righteous hatred of the president from showing, and hatred is never a good look. Henry Hyde tried to evoke the cheapest kind of patriotism by bringing up the dead soldiers beneath the white crosses in the American cemetery in Normandy, suggesting that the circumstances behind the impeachment trial were not what they had fought for. As a veteran of that war and a friend of a couple of the soldiers under those white crosses, I was offended by that reference and glad when White House counsel Charles Ruff said in reply that his father had fought in that war, but not for either side in this case. I couldn't stand Lindsey Graham's folksy, down-home, I'm-just-a-southern-boy speechifying. He said "ain't" a lot. I'd seen his mean streak show on his face on television during the House Judiciary hearings, when he spoke about the president's planting the stalker story, his voice dripping with disgust. Even a public outing of handholding on a cozy banquette at the Palm restaurant with Laura Ingraham, the right-wing blonde pundit of MSNBC, which was widely reported in the gossip columns, didn't change his image. Bob Barr was another one I had trouble with. It's probably unfair to say this, but I couldn't look at him without thinking of Hustler publisher Larry Flynt's accusation concerning his second wife's abortion, which she says he paid for while wooing wife No. 3. In my notes of January 26, made during a speech by House manager Bill McCollum, I wrote, "Hardly any of the Democratic senators are really listening to him. Senators Kennedy and Biden, sitting next to each other, are carrying on a conversation. Some are reading, some writing. They've heard it all before, over and over."

You know you're at the A-list party in town whenever Katharine Graham, former publisher of The Washington Post, walks into someone's living room, exuding her special aura of class and power. "Hi, Kay," everyone says, "Hi, Kay," as she heads for a sofa or her place at the table. Seated next to her one night at a dinner in the home of Margaret Carlson, a columnist for Time magazine, who was also covering the impeachment trial, I got shy and could think of nothing interesting to say, but Mrs. Graham—I didn't dare call her Kay—immediately started raving about the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, whose concert she had attended that afternoon at the Kennedy Center. The guests were all so in that they seemed to know everything before it happened. Andrea Mitchell, the chief foreign-affairs correspondent for NBC News, was on my other side. She repeated a joke that Democratic senator John Breaux of Louisiana had told at the Alfalfa Club dinner, an annual Washington roast: What did President Clinton and the Pope talk about in St. Louis? The Nine Commandments. Andrea is married to Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, who was seated at the other end of the table, between Ann Jordan, Vernon Jordan's wife, and the hostess. Vernon was on the other side of Margaret Carlson. Elsewhere at the table were Jim Lehrer of PBS's NewsHour and his novelist wife, Kate, and my old friend George Stevens Jr., the son of the great film director George Stevens, who had left Hollywood in 1962 to work at the United States Information Agency under President Kennedy. He stayed on in Washington and married Elizabeth Guest, and he now runs the Kennedy Center Honors program, plays golf with Vernon Jordan, and is close to the First Family. The Stevenses had had the Clintons to early dinner at their house the previous night and then gone on to the Kennedy Center to see Bernadette Peters in Annie Get Your Gun, which was trying out in Washington before moving to Broadway. Ann Jordan had been in the party, as had Peter Stone, who had revised the book for the current revival of the musical, and his wife, Mary. Their arrival at the theater was unannounced, but George said that in all his years at the Kennedy Center he had never heard an ovation as loud or as long as the one the Clintons received when the audience became aware of their presence in the presidential box.

For some reason the name of the lawyer John Dean, long associated with the Nixon Watergate scandal, came up. It provided me with the chance to make my single contribution to the dinner-table conversation. Dean was currently back in the public eye as an expert witness on impeachment on MSNBC. I remembered that his wife's name was Maureen, or Mo. I asked Andrea Mitchell if she knew who had been the ghostwriter of Maureen Dean's trashy novel Washington Wives. "No," replied Andrea. "Lucianne Goldberg," I said. She promptly called for silence at the table. "Tell them what you just told me," she said. I repeated my nugget.

The day of the election, Lucianne said, "You mark my words, he'll never finish out this term."

My long friendship with Lucianne Goldberg came to an end—not without regret—over Linda Tripp's surreptitious taping of Monica Lewinsky. I found it abhorrent that someone like Tripp—"that paragon of faithful friendship," as David Kendall, Bill Clinton's personal lawyer, called her—could destroy the president of the United States. Lucianne and I met in 1985, during the second Claus von Bülow trial for the attempted murder of his wife. Lucianne was the literary agent for a mysterious young man named David Marriott, who was variously described by the press as an undertaker, a male prostitute, and a drug dealer. He was also a sort of forerunner of Linda Tripp. In the August 1985 issue of this magazine, I wrote, "Marriott further revealed that he had secreted a tape recorder in his Jockey shorts and taped von Bülow, [von Büllow's mistress Andrea] Reynolds, [local priest] Father Magaldi, and [lawyer] Alan Dershowitz in compromising conversations." For nearly a week Marriott held sway in Providence—where the trial took place—granting interviews, riding around in limousines, being famous. There was going to be a book. I remember hearing the tapes, whose sound quality was what you would expect, given the location of the recorder. The voices were distinguishable, but the content of the conversations, while suspicious in nature, was not incriminating. There was never a book. Marriott dropped out of sight, but Lucianne and I hit it off and became friends. We enjoyed each other's company. In my 1997 novel, Another City, Not My Own, in which I based the character Gus Bailey on myself, I wrote on page 12:

Gus had a friend named Lucianne Goldberg, whom he referred to as his "telephone friend." They saw each other only a couple of times a year, but they talked every day, usually after they had read all the morning papers, and hashed over the news. Like Gus, Lucianne was a newspaper junkie. Like Gus, she had contacts in high places. Like Gus, she was a font of daily information They saw things the same way, although she had considerably less tolerance for President Clinton than Gus did.

Lucianne's feelings about Bill Clinton didn't bother me, since all my Republican friends disliked him, but I remained steadfast in my own convictions. On the day of his second election—a cause of rejoicing for me—Lucianne said, "You mark my words, he'll never finish out this term."

In May 1996, nearly three years after Vincent Foster's suicide, she told me about a government employee named Linda Tripp, who had come to her to suggest a book about Foster's death, as well as about goings-on in the Clinton White House. Tripp had served Vince Foster his last hamburger, and she is thought to be one of the last people to have seen him alive. Lucianne assigned a ghostwriter to prepare a book proposal, but then Tripp backed away from the project, fearful of losing her job. More than a year later, Lucianne asked me, "Do you remember a woman I told you about called Linda Tripp?" I remembered only that she had served Vince Foster his last hamburger. She was back with a new story, concerning a very young intern in the White House who was having an affair with the president. Although I have subsequently heard Goldberg deny this on television, it was my understanding that Tripp's second visit was about another book. For some reason, I never reacted to the story as I probably should have, thinking that this was going to be just another book like Gary Aldrich's, about the president's sexual escapades, gossip with no proof, the kind of cheesy book that makes a splash and is quickly forgotten. I remember saying something totally inadequate, like "Wouldn't you think he'd be more careful, with Paula Jones breathing down his neck?" I never really believed the story. That it might lead to the impeachment of the president never occurred to me.

I began to get almost daily bulletins about the affair. I learned how brokenhearted the young woman was. I heard about the semen stain on the dress. It was such a tawdry story that it seemed too improbable to credit. Then I heard that Linda Tripp was taping her telephone calls with the young woman, without her knowledge. That was the first time I reacted. "Isn't that illegal?" I asked. I began to listen to Goldberg's retelling of Tripp's stories in a different way, but I did not keep records, still not picking up on the fact that a historic moment was happening in front of me. Lucianne had bought her son Jonah an apartment in Washington, and it was there, she would tell me, that she met with Linda Tripp and Mike Isikoff of Newsweek magazine.

In November 1997, I was having lunch at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York. Across the room I saw Vernon Jordan, with whom I was acquainted. As he left the restaurant, he stopped by my table. Knowing of his closeness with Clinton, I decided to warn him that an intern of the president's was being taped. I didn't feel that I needed to go into sordid details; I would just tell him the basic facts. But the story suddenly seemed so utterly absurd that I choked. I thought that no one could be such a goddamned fool as to have an affair with a twenty-something intern in the Oval Office and ejaculate on her dress while being investigated by Judge Starr, so I simply mumbled, "Give my best to the president."

At one point Lucianne told me, "Ken Starr has put a wire on Linda." By then I was deeply bothered by the story, but I didn't know what to do with the information. I knew of three other people who were hearing these same things from Lucianne. Because of my friendship with her, this was not a story I could run with. However, since I move in media circles, I began to tell it at parties in the hope that someone would pick up on it. I was chastised by Ahmet Ertegun for using the word "cum" instead of "semen" when I told the story at a dinner at Henry and Louise Grunwald's apartment in New York, and I remember calling the next morning to apologize to Louise for my trashy mouth—but that's the kind of story this is.

On January 21, 1998, the Monica Lewinsky story broke. I was in Paris working on an article, and I watched Lucianne on television talking to reporters in front of her West Side apartment building, saying that she had told Tripp how to tape Lewinsky's calls, and that the resulting tapes had been given to Ken Starr. I kicked myself around the block. Lucianne became a national celebrity. The New York Times reported that I was her friend, and I was asked to go on chat shows to discuss her, but I declined. Our phone conversations became stilted.

I had another connection with her: Mark Fuhrman, the controversial detective from the O. J. Simpson trial, who had written a best-seller about that case called Murder in Brentwood. Lucianne Goldberg was his literary agent. She was looking for an unsolved murder for Fuhrman to write about. I had received relevant information about the 1975 murder of Martha Moxley in Greenwich, Connecticut, in which Tommy and Michael Skakel, nephews of Ethel Skakel Kennedy's, would become the main suspects. Since I had already written about that case in my novel A Season in Purgatory, I gave the information to Lucianne, who gave it to Fuhrman, who developed it into a successful book, Murder in Greenwich.

In August 1998, I gave a lecture at the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton, Long Island, in which I tied the two stories— Monica Lewinsky and the Skakels—together, with Lucianne being the link to both. A few days later, an item about my lecture appeared in Neal Travis's column in the New York Post, saying how I had almost told Vernon Jordan the story. Soon after that, I received identical handwritten faxes at my New York apartment and my Connecticut home, saying, "You are playing with fire, Nick. I am going to have to answer this very publically. Lucianne." I faxed back that I hadn't dissed her in my Bridgehampton lecture. I said that I had merely told about what was happening in my life, and that Linda Tripp and the Moxley murder were both connected to her. We have not spoken since. I have watched her on television, with Larry King, Chris Matthews, or John Hockenberry, and I heard her tell the Today show's Matt Lauer that Linda Tripp was a patriot. She was unrecognizable to me as the friend I used to know. We used to laugh about Marv Albert's toupee and the lady in the hotel room who pulled it off. We used to do numbers on Johnnie Cochran and Bob Shapiro during the O. J. Simpson trial. But I didn't know her anymore.

You can't touch me. You don't know who the fuck I am.

—Ryan Michael Tripp, 23-year-old son of Linda Tripp, to a police officer outside the Santa Fe Cafe in College Park, Maryland, before being arrested and charged with disorderly conduct, disturbing the peace, and obstructing and hindering justice.

'Oh, here comes your friend Eunice Shriver," said Maureen Orth, my fellow writer on this magazine, as we stood in the elegant drawing room of Smith and Elizabeth Bagley's house in Georgetown and watched the other guests arrive for dinner. There's Senator Barbara Boxer of California ... There's Congressman Dingell of Michigan ... There's Congresswoman Loretta Sanchez, who just defeated Bob Dornan in California ... You must see the indoor swimming pool—it's divine. That night I was standing in for Maureen's husband, Tim Russert, who was on NBC talking about the impeachment and Monica, which is what we were all going to be talking about at dinner. Smith Bagley, an heir to the Reynolds tobacco fortune, is a major contributor to the Democratic Party. The occasion was a dinner for former ambassador to the United Nations Bill Richardson and his wife, Barbara. Richardson is now secretary of energy in Clinton's Cabinet, and is being talked of as a possible running mate with Al Gore in the 2000 presidential race.

"Why? Is there a problem?" asked our hostess, the Honorable Elizabeth Bagley, President Clinton's ambassador to Portugal for three years. Maureen's tone had suggested that there might be.

The Kennedys always seem to bristle when I come within their sight lines, ever since I covered the William Kennedy Smith rape trial in West Palm Beach for Vanity Fair and then wrote A Season in Purgatory, based on the murder of Martha Moxley, a case that has been before a grand jury in Connecticut this year, owing in some measure to my efforts. The day before, Senator Kennedy had huffed by me in a hall in the Capitol. They do not hold me in high esteem, even Pat, with whom I used to be friends years ago, when she was married to Peter Lawford and we were neighbors on the beach in Santa Monica.

I had seen Pat with Eunice Shriver in the gallery of the Senate the day before. They were fascinating to observe as they watched and listened intently to House manager Lindsey Graham, sometimes leaning forward, sometimes whispering to each other, their faces etched with the sorrows they have borne. I was struck by the American history bound up in these two ladies—sisters of an assassinated president, sisters of an assassinated presidential candidate, sisters of a senator sitting below them as a participant in the impeachment. Awesome, really.

I've been to enough dinner parties in my day to recognize the flurry of covert activity involved in the switching of place cards at the last minute, and I was quite aware of it that evening. "Thank God I didn't ask Ethel," I heard the hostess say in passing as she re-entered the living room to greet Sarge and Eunice Shriver.

Hi, Max. It's a little heavy going, isn't it? I had to have two cups of coffee.

—Senator Ted Kennedy, overheard talking to Georgia Democratic senator Max Cleland after one lengthy session of speeches.

It was interesting to watch it all from above. During breaks, you could hear senatorial conversations wafting up. Democratic senator Bob Kerrey of Nebraska took the most copious notes. He had an 8-by-10-inch notebook, and he wrote on both sides of the paper in complete sentences. After observing him for weeks, I began to wonder if maybe he was using the time to write a book. Republican senator Bill Roth of Delaware has the worst toupee. House manager Steve Chabot of Ohio has the worst comb-over; it comes from two directions. The most attentive individual was 96-year-old Strom Thurmond, Republican from South Carolina, who sat up rigidly listening to every word and never once nodded off. He went over to presidential counsel Cheryl Mills after she delivered her speech and gallantly congratulated her on it, even though he was going to vote to remove the president from office. Jesse Helms did nod off, fairly often in fact, with his head down on his chest. Colorado senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, who used to be a Democrat and changed to a Republican, wears the only ponytail in the Senate. Without any sort of fanfare, he would pay for coffee for the tourists waiting in line outside the Capitol to get in to watch the trial. During breaks, Judge Rehnquist had tea and Edy's ice cream served to him by Senate doorkeepers.

I went to a Super Bowl Sunday party at the Georgetown home of Lloyd Cutler, former White House counsel for President Clinton, and his wife, the artist Polly Kraft. Polly's another one of the social forces in Washington. That was where I got to meet presidential special counsel Gregory Craig, one of the very classy members of the president's legal team, who had given a great speech early in the trial. He couldn't talk about the trial, being part of it, but he talked about his regular Sunday-morning football games with Stuart Taylor of The National Journal and Evan Thomas of Newsweek, two of President Clinton's severest critics. That's Washington, people said. Evan Thomas asked me if I knew Warren Beatty's phone number. He's writing a book about Bobby Kennedy and needed some information. Three of the couples I knew at the party had just come back from a large and very successful house party at Camp David, given by Bill and Hillary, as they all called the First Couple. They didn't want to be identified, but I found out from one of the group that Harvey Weinstein, the co-chairman of Miramax, and his wife had been there. Weinstein took along a print of Shakespeare in Love, but Hillary had already seen it at the premiere in New York. Carly Simon and her husband, James Hart, were also at Camp David, and a couple of Wall Street billionaires. Everyone spoke about the tenderness that had existed between Bill and Hillary throughout the weekend. "There was enormous affection," one said. "We took wonderful walks," said another. "The president was fascinating." All their memories were of a tranquil nature. I had to remind myself that that tranquillity existed in the midst of an impeachment trial, which was to pick up again the following morning. People said that the president thrives in chaos.

Linda Tripp told the grand jury that one of her jobs at the Pentagon was to sort out photographs of the president. In her office she had jumbo shots of Clinton with members of different branches of the military and the government, which are mounted on pressboard and hung in the White House in a constantly changing exhibition to depict the president's activities. When Monica Lewinsky met Tripp in her office she saw the jumbo shots, asked for one, and received it, and so the unlikely and fateful friendship between the two women began. That such a relationship should have been brought about by a chance encounter over a photo blowup of Bill Clinton—whom one woman loathed and the other woman loved—is better than any novelist could make up. It's just too far-fetched. If I were to write the story as a novel, I'd play into the right-wing conspiracy theory and have the jumbo shots of Clinton in Tripp's office be a setup to lure the lovesick former intern into the older woman's lair for the nefarious business of bringing down the president.

I wonder what kind of life Linda Tripp will have ahead of her. Friendless, I would think, although her Pentagon job is probably secure for life. In March of this year I heard her on television with Cokie Roberts and Sam Donaldson, calling Roberts Cokie and Donaldson Sam—like the star she has become with her new look—and telling them that if she were to write a book, Monica Lewinsky would be only a chapter. The majority of the book, she said, would deal with what she knows about the Clinton White House, including Hillary Clinton, and the implication was that she knows plenty. It's not a book I would ever read, but at least she has a famous agent.

In the novel, I'd probably have to have a murder too, or it wouldn't seem like one of my books. There was obviously no murder in the impeachment story, or so I thought, but then the darndest thing happened: one fell right into my lap. Difficulties with a new computer led me to an expert who not only solved my technical problems but also flashed a badge and revealed to me that he was a Washington, D.C., cop. He asked if I had ever heard of a girl named Mary Caitrin Mahoney, a former White House intern. I hadn't. Known as Caity, she had worked on Bill Clinton's campaign in 1992. Following his victory, she obtained a job as a White House intern, giving tours. She left the White House to get a degree in women's studies at Towson State University, near Baltimore. Then she returned to Washington and took a job as the night manager of a Starbucks coffee shop on the edge of Georgetown. There she and two fellow employees were murdered gangland-style on July 6, 1997, as they were cleaning up after closing time.

Ten shots from two different guns were fired, at least three of them into Caity Mahoney. The fact that the gunfire was not heard by neighbors on a quiet Sunday night led some to speculate that silencers had been used. Nearly unrecognizable, Caity Mahoney had been shot first in the chest, police believed. She must have raised her hands to shield herself, because one bullet had pierced her hands and hit her face. Then she was shot in the back of the head. Although there were no signs of forced entry, and nothing was taken from the cash register, and the safe, which had more than $10,000 in it, was not opened, the police categorized the triple murder as an attempted robbery. On March 6 of this year, Carl Cooper, a 29-year-old man with a criminal record, was charged with the murders.

During this period of humiliation for the First Couple, former senator Bob Dole, whom Clinton had defeated in 1996 for the highest office in the land, was a constant presence in television commercials, discussing erectile dysfunction for Viagra, while his wife, Elizabeth, looking fit and satisfied, flirted with throwing her hat into the ring for the presidency.

Elsewhere in the city, in certain posh houses where ambassadors come to dinner instead of politicians, the impeachment and the president were tut-tutted over in short order, and conversation quickly moved on to other things, such as the funeral in Upperville, Virginia, of the nonagenarian billionaire Paul Mellon, who died on February 1, leaving much of his fortune to the National Gallery in Washington. Bunny Mellon, his widow, who had been such a great friend of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis's, was to receive $110 million outright. Hubert de Givenchy, the retired couturier who had dressed Bunny Mellon for years, arrived from Paris with the hat she was to wear at the funeral. There was consternation over whether the woman well known for many years as Mellon's mistress, old now and ill, would attend. She didn't, but there was a place for her. Nothing trashy about that.

One night Jeffrey Toobin and I went to the Palm for dinner. Jeffrey is writing a book about the impeachment. That day in the gallery he had passed me a note about Cheryl Mills during her brilliant speech: "Don't you love her?" I did. The Palm, which is the most fun place in town, was jumping with the media crowd. There's Roger Cossack of Burden of Proof... There's Georgette Mosbacher. She's here for the Republican National Committee annual meeting. Jeffrey and I had been together at the O. J. Simpson trial. We saw things the same way. He referred to one of the House managers as "the Pervert" because of his obsessive interest in the particulars of the sexual behavior of Monica and Bill, as detailed in the Starr report. Later, we joined P. J. O'Rourke's table for coffee. P.J. hates the president, but his diatribe was hilarious. An attractive lady who had worked at one of the networks told a story of being sent out to a golf course to tell the president that his interview with an important newsperson would begin in the clubhouse in 20 minutes. She said the president turned to his companion in the golf cart and said about her, "Nice ass." Although she was a Democrat, she said, her admiration for him evaporated on the spot.

"Yeah, but what are we gonna do when I'm seventy-five and I have to pee thirty times a day?"

—President Clinton to Monica Lewinsky, discussing their possible togetherness after his term in office, from Monica's Story, by Andrew Morton.

'I'm beginning to change my feelings about the president," I said on the telephone to a friend in New York.

"You're just being influenced by Sally Quinn," she replied, for she had shared my admiration for Clinton.

"No, no. I got there myself," I protested.

After two weeks in town, I had stopped saying, "It's only about a blow job." It didn't sound convincing anymore. The Willard hotel, where I was staying, was separated from the White House by only the Treasury building. On my walks, I always went by the White House and stopped to stare in. One night, during my fourth week in Washington, I was looking in at the Oval Office from behind the fence when a really cheap thought popped into my head. I wondered if any of the president's semen had missed Monica's dress and splattered onto the carpet. It was that thought that did it for me. Recriminations, long harbored, erupted. He had trashed that office the way some rock stars trash hotel rooms. However you look at it, there was never any beauty or dignity in the Clinton-Lewinsky romance. This was no Edward VIII and Mrs. Simpson. From the beginning it was a lurid arrangement, about getting off, or getting to the point of getting off and then holding it back—as if that were not violating the sanctity of the marriage upstairs—except for that one time when he stained her dress and launched the words "semen" and "blow job" into everyday conversations all across America.

At a Lincoln's-birthday party given by Washington Post writer Walter Pincus and his wife, Ann, the star of the night was presidential aide Sidney Blumenthal, who was very much in the news after his former friend Christopher Hitchens signed an affidavit casting doubt on the truth of his statement-made under oath in his videotaped deposition shown in the Senate—that he had not spread the word that Monica Lewinsky was a stalker. It was the talk of the town for several days and much written about in The Washington Post and The New York Times. It had been the lead story that week on Tim Russert's Meet the Press. I was speaking to Jackie Blumenthal, Sidney's wife, whom I had never met. We were talking about her position as head of the White House fellows program. Suddenly she said, "Oh, dear." I said, "What?" She said, "Someone just came in who I assured Sidney wouldn't be here." I turned and saw Vernon and Ann Jordan coming into the room. Vernon was making his usual massive entrance, wonderfully dressed as always, and people were greeting him. I saw that Sidney saw Vernon coming toward us. Vernon spoke to Jackie. To me he said, "What's the first line of your article going to be?" Then he turned and stood face-to-face with Sidney. Vernon said, "I kept the chair warm for you." He was referring to the red leather chair on which they had both sat during the videotaping of their depositions. Then both of them smiled, and they shook hands. I don't know what that moment meant, but if I ever use that scene in a novel, I expect to find out.

There was a bomb scare in the Senate within a half-hour of the president's being acquitted. Police and sniffing dogs were everywhere. People poured down the stairways to evacuate the building. Merri Baker, from the Senate Press Gallery, introduced me to Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, who was ahead of me on the stairs, leaving the building with his staff. The senator, still dapper at 81, wears bow ties and colorful vests. I had heard him give an interview to Lisa Myers of NBC in which he said that he was troubled by the arrogance of the president when he had his victory rally with House Democrats right after being impeached. Nevertheless, Byrd had voted to acquit. "I wrote my speech 15 times," he told me, "and I was only halfway through when the chief justice told me that I'd spoken for 22 minutes." His retinue continued to hurry him along. Just then, Eunice Shriver and Patricia Lawford rushed past in another direction, behind Senator Kennedy, who was being pursued by a television crew.

"Hi, Dominick," Pat said. "Hi, Pat," I replied. It was the first time we had spoken in years.

Both Barbara Walters and Sally Quinn had told me in advance that I'd be surprised by Monica Lewinsky. She's not at all the Valley Girl you think she's going to be, each of them said in a different way. Barbara was preparing to interview her, and she was having trouble with Ken Starr over Monica's release. Sally had met her the year before at a book party for Larry King in Washington, and they had talked for 15 minutes. "She's very smart, dresses well," said Sally. "She had on a black Chanel suit with the white gardenia on the shoulder, and she's very funny."

I was quite taken with Monica Lewinsky on video when sections of her deposition were played in the Senate one Saturday morning. Watching a hundred senators watch her on the monitors was quite a sight. There had been times in the preceding weeks when some senators had been openly bored with the proceedings, but Monica brought them all back to full attention. She was different from what I had expected. One of the Republican senators had described her as "heartbreakingly young." She wasn't heartbreakingly young at all. She was poised, smart, funny, and, seemingly at least, assured. I liked her, although I hadn't wanted to like her, and I enjoyed watching her outmaneuver House manager Ed Bryant. The House managers didn't change one senator's vote for impeachment with Monica's testimony. She had become a pro at testifying, and was way ahead of them. I wrote her a letter. I said that she had emerged as the class act of the trial, though no one would have thought that a year ago. I asked her if she would talk with me after her interview with Barbara and her interview for Britain's Channel 4, for which she was getting paid a reported $650,000. I heard back from John Scanlon, who was handling her public relations, and whom I happen to know, that it was not impossible. He even set a tentative lunch date for two days after Lewinsky's interview with Barbara Walters.

I watched that interview in Barbara Walters's apartment in New York, along with a small group of people who had worked on the program and some close friends of Barbara's, including David Frost, another of the great interviewers. Outside on Fifth Avenue, there was no traffic. Seventy million people were home watching Monica and Barbara. I was mesmerized by the interview. I kept thinking, This is American history we're watching. Actresses will play this scene in movies and plays and mini-series in the new century ahead of us. Barbara moved about, sitting on the arm of one person's chair, then moving on to another, never taking her eyes off the screen. During the commercials, everyone talked about Monica. Her hair. Her lipstick. Her laughter. Her tears. "I don't think the president is coming off too well," I whispered to my friend Casey Ribicoff, widow of the late senator Abraham Ribicoff, and then the commercial was over. Midway or so in the interview, the local ABC feed began flashing a storm warning across the bottom of the screen below their faces, which was very distracting. David Westin, the president of ABC News, was present. He made a call to the station, and the distraction stopped. It's called Hanging Out with the Brass.

At times Monica reminded me of the obsessed women in Francois Truffaut's The Story of Adele H. and Stephen Sondheim's Passion. I can't remember exactly when it happened—and I think maybe it wouldn't have happened if the show hadn't lasted two hours—but after about an hour and a half I began to lose patience with her. Perhaps it was her saying, "I don't think that my relationship hurt the job he was doing. It didn't hurt the job I was doing"—as if you could equate their careers. Perhaps it was the newly revealed abortion, resulting from her affair with the other guy, Thomas Longstreth, whom she had taken up with after her affair with the president ended and before it started up again. The next day I bought Andrew Morton's book Monica's Story and read straight through it. Having lived in Beverly Hills for many years, I have known my share of Monica Lewinskys, and she was true to form. I found her exasperating, self-indulgent, spoiled, unrealistic, and nice. I felt sorry for her that she was the only girl in her class who didn't get invited to Tori Spelling's birthday party when they were kids, but the story also made me roar with laughter, so Beverly Hills was it. The book is incredibly revealing about the president. The affair was so utterly tacky, and his behavior was so low-rent. The episode in Room 1012 of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, where Ken Starr's thugs terrify Monica as the hideous Linda Tripp watches, was chilling, but I admired Monica for not caving in.

As for our lunch date, it was canceled that morning. She had just flown in from Los Angeles the night before, and she was leaving for London the next day, and she wasn't feeling well. It was not a great disappointment. By that time, I knew everything I needed to know about Monica Lewinsky.

Yes, the president was acquitted, as he should have been. There was none of the drama the O. J. Simpson acquittal had. There was no surprise element. Everyone but the House managers knew from the beginning that it was going to end up as it did. Senator Dianne Feinstein's censure proposal was dismissed, and consequently a lot of people felt that the president got off easy, considering what he had put the country through. I don't think he got off easy. The president's close friend former senator Dale Bumpers laid it out pretty well when he said on the floor of the Senate that the Clintons had been "about as decimated as a family can get. The relationship between husband and wife, father and child, has been incredibly strained, if not destroyed." I often wonder what it must feel like to have one of your lies— which the whole country knows is a lie—played over and over and over again on television, as it will be played for the rest of Bill Clinton's life: "I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky," he says each time, with a forceful hand gesture to emphasize his conviction in the lie. Any father who has ever let down one of his children knows what a terrible feeling that is, and the president has let his daughter down in the most painful and public way. How he must suffer for that. How shaming it must be for him to have raised Monica Lewinsky to a historical status nearly equal to the historical status of his distinguished wife. No matter what good he may do in recompense in the months of his presidency left to him, the names Monica Lewinsky, Paula Jones, Gennifer Flowers, Kathleen Willey, and Juanita Broaddrick will always be hurled in his face by someone in the crowd, as Sam Donaldson demonstrated at the president's first press conference in nearly a year, when he was talking about Kosovo and Donaldson asked him about Juanita Broaddrick and used the word "rape." Those are moments that must hurt, especially with everyone staring at him. "Well, he brought it on himself," people say to me, which is true. But I have to admit something: I want to see the guy get up again. I want him to do something wonderful in the months ahead, before he walks across the White House lawn for the last time and waves good-bye as he gets into the helicopter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now