Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

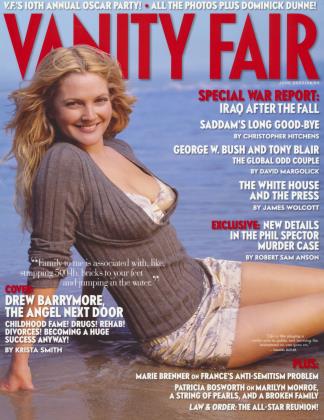

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAgainst a wartime backdrop, Hollywood's Oscarfest had a surreal edge. The author couldn't help enjoying it, though, whether he was getting Barbra Streisand's political views, cheering the winners at the V.F. party with pregnant Wendi Deng (Mrs. Rupert Murdoch), or patching things up with Liz Taylor

June 2003 Dominick Dunne Mark SeligerAgainst a wartime backdrop, Hollywood's Oscarfest had a surreal edge. The author couldn't help enjoying it, though, whether he was getting Barbra Streisand's political views, cheering the winners at the V.F. party with pregnant Wendi Deng (Mrs. Rupert Murdoch), or patching things up with Liz Taylor

June 2003 Dominick Dunne Mark SeligerIt seemed almost obscene, on the second day of the war with Iraq, to be flying to Los Angeles for five days of nonstop festivities having to do with the Academy Awards and the Vanity Fair Oscar party, which for years has been the place to be seen on that night of Hollywood nights. I arrived at J.F.K. two hours ahead of time to deal with the crowds of people I expected to find fleeing New York and the threat of terrorist attacks. No such thing. The airport was virtually empty, although there were a lot of soldiers in camouflage uniforms carrying guns. I did not have to wait in line at the screening machines or have a body search, and my flight was half empty. It left New York and arrived at LAX exactly on schedule, and there was a car and driver to take me to the Beverly Hills Hotel, which I think of as my home away from home when I'm on the West Coast.

Let me say right up at the top that I felt slightly guilty all the while I was there having a good time. It was a peculiar mix of emotions to be watching the war on CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News while changing clothes to go on to the next party. At one point I got so upset with myself that I took off my black tie and dinner jacket and put on a long tie and dark suit, as if that might help the war effort in some small way. As every Hollywood person knows, Academy Awards week is the biggest week of the year, more festive than any holiday season. Right up until airtime this year, the awards ceremony was in danger of being canceled, but somehow that gave an exciting edge to the proceedings—like dancing on the Titanic. I'm sure the whole crowd at the ceremony felt the strangeness in the air, but they all managed to look wonderful at the same time.

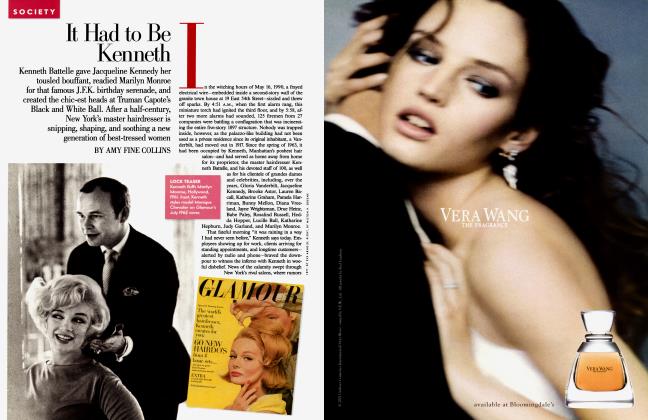

This diary is going to be one long name-drop, but namedropping is in my blood, and I'm not the least bit embarrassed about it. The restaurants were packed to the rafters. Spago and Mr. Chow were as glamorous as ever, and the Polo Lounge is hot again. The best place to stare at famous people, however, is the coffee-shop counter at the Beverly Hills Hotel, where Ruth Silungan, who knows everybody in town, runs the show, making juice, pouring coffee, taking orders, and still finding time to chat. "That's Dylan Douglas, Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones's two-and-a-half-year-old son," she said, pointing to a cute little guy sitting on a stool eating a waffle and talking a mile a minute to his nanny. Wherever you were, whether it was in Betsy Bloomingdale's beautiful dining room, with all that silver and crystal and candlelight, or at superagent Ed Limato's yearly celebrity-filled party at his Beverly Hills mansion, where George Raft and Betty Grable carried on their famous affair back in the 40s, people were talking movies only about half of the time. One minute Barbra Streisand was telling me that Halliburton, the firm of which Vice President Richard Cheney used to be chief executive, must not be allowed to get the contract to rebuild Baghdad. The next, Ben Affleck was introducing me to Jennifer Lopez, both of them looking so comfortable in their extraordinary fame that even other famous people were staring at them. At a small lunch that Nancy Reagan gave at the Hotel Bel-Air, I met Rob Marshall, who had directed Chicago, his first movie, so terrifically. When he left, he said he was going to rehearse Catherine Zeta-Jones and Queen Latifah for the number they would sing together at the awards ceremony.

Barry Diller and Diane Von Furstenberg gave an elegant picnic lunch at their house, with Oriental rugs strewn all over the enormous lawn and beautiful people of all ages moving about, drinking, gossiping, hugging, kissing, talking war, talking movies. One of the most beautiful women in Hollywood asked me if I would introduce her to detective Mark Fuhrman sometime, and I said sure. Warren Beatty looked great. I talked to Michael Eisner, the head of Disney, about Barbara Walters's insightful interview with Robert Blake, which had gotten me interested in covering the star's trial. When it was time to eat lunch, Wendy Stark and I sat with Barry Humphries, who is better known as Dame Edna, and his wife, my friend Lizzie Spender, the daughter of the late British poet Stephen Spender. One of the prettiest women in the large crowd that day was my ex-daughter-in-law, the actress-model Carey Lowell, who is now Mrs. Richard Gere. Carey was there with my granddaughter Hannah Dunne, who at 13 looked right at home in that fancy international setting. I could go on and on. Anyway, it was like that for several days.

I haven't seen anyone get a drink in the face for a long time.

As a voting member of the Academy, I'm happy to say that I voted for all four of the actors who won: Nicole Kidman, Adrien Brody, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Chris Cooper. Minus the red carpet and the fashion-and-jewelry show that has dominated the awards for years, the program went on in a dignified style under the capable aegis of host Steve Martin, who has class, wit, and brains. After Michael Moore, who won for best documentary, turned his acceptance speech into an anti-war rant—"Shame on you, Mr. Bush," he said to cheers and boos—Martin came up with the funniest line of the night, which had to be an ad-lib since it could not have been scripted: "It is so lovely backstage. The Teamsters are helping Michael Moore into the trunk of his limo." I watched the ceremony at the Vanity Fair dinner preceding the Oscar party, in a dramatically decorated Mortons restaurant, seated between Mrs. Rupert Murdoch, the wife of the media baron, who goes by her maiden name, Wendi Deng, and is pregnant with their second child, and Mrs. Ahmet Ertegun, the wife of the record czar, who is prominently known in decorating circles as Mica Ertegun. Like me, the two women are both ardent movie fans, and they followed the awards closely on the big TV screens mounted all around the room. There were so many wonderful moments this year, among them Sean Connery saying simply "Catherine," in a tender voice, when he announced Catherine Zeta-Jones as the winner for best supporting actress; the elegant speech Peter O'Toole made accepting an honorary Oscar for an outstanding career in movies; and father and son Kirk and Michael Douglas simultaneously announcing Chicago as best picture. I was delighted by the sheer elegance of Olivia de Havilland, who lives in Paris. She brought to mind an era when she was one of Hollywood's greatest actresses. Her Academy Award-winning sister, Joan Fontaine, with whom she has maintained a lifelong rivalry, did not attend.

For me, the high point of the evening was the surprise win in the best-actor category of the relatively unknown Adrien Brody for The Pianist, presented by last year's best actress, Halle Berry. It is rare, in our sophisticated world, to witness total, utter, unfalsified joy, as we did watching the young actor experience what must have been the greatest moment of his life. I loved it when he took the gorgeous Halle Berry in his arms and gave her a Rudolph Valentino-style, bend-over-backward kiss. I thought Berry was a very good sport about his unexpected show of passion, but I later read in the tabloids that she wasn't thrilled with the tongue job and said Brody wouldn't have done it if Meryl Streep had been the one handing him his Oscar. No matter: it was a wonderful moment, which will undoubtedly be replayed in Oscar ceremonies for years to come.

I was quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying that everyone ends up at the Vanity Fair party, and indeed they do. When Nicole Kidman, with her best-actress Oscar in hand, walked into the party, looking exactly the way a great star should look, the crowd cheered her. Edward Norton came up and introduced me to Salma Hayek, who was nominated for her performance in Frida, which she fought to get made. I had a great time with Megan Mullally of Will & Grace, who is my candidate for funniest woman on television. I see her only once a year, at the Vanity Fair party, but we pick right up from the year before. I met Buzz Aldrin, the astronaut, and his wife, Lois, who said she would like me to write a book about the late Ricky and Sandra Portanova, of Houston and Acapulco, which is a fascinating story, with their almost simultaneous deaths three years ago, but I told her I was already overcommitted. In one corner of the party, Robert Evans and Jeff Berg, the best friend and longtime agent, respectively, of Roman Polanski, tried to get through to him in Paris to congratulate him on his win as best director, but Polanski was not in his apartment. He had taken a suite at the Plaza Athénée, across the street, in order to watch the show with his wife and friends.

No party, regardless of how many stars there are to stare at, is memorable without an incident that becomes the talk of the town the next day. Such an incident occurred at our party, when Ed Limato threw a drink in the face of Richard Johnson, the gossip columnist for "Page She" in the New York Post, which is occasionally mean-spirited, especially about Hollywood people. Johnson had written that Limato's annual Oscar party, to which the columnist had not been invited, would be boycotted because of the movie Limato's client Mel Gibson was producing, a film called The Passion, about the role the Jews played in the Crucifixion of Jesus. A powerhouse Hollywood agent and a powerhouse New York gossip columnist venting their mutual hatred at a dressy party was a sight I hate to have missed, but I happened to be looking in another direction at that moment. I haven't seen anyone get a drink in the face for a long time. It must have been humiliating. It reminds me of the time back in the 60s when Frank Sinatra paid a waiter to slug me in a nightclub called the Daisy. I remember that everyone was looking, and that I wanted to die, I was so embarrassed. At least it wasn't red wine that Limato threw at Johnson; it was a martini, and observers said that the olive bounced off Johnson's nose. I was surprised that Johnson made no mention of the incident the following day on "Page Six," where there was lengthy coverage of the night's festivities. It was definitely the top gossip item among people I talked to, and Johnson certainly would have written about it if it had happened to anyone but him.

I had brunch the day of the awards with three reporter friends from the Menendez and Simpson trials: Linda Deutsch, the doyenne of the Associated Press; Mary Jane Stevenson, of Court TV; and Shoreen Maghame, who at the time of the trials was reporting for ABC. We had a grand reunion. My Hollywood experience ended with a very welcome reconciliation telephone call with Elizabeth Taylor. We've been sort of on the outs since she turned down an introduction she had asked me to write for her recent book about her jewel collection. She told me that she hadn't actually read my introduction, which I had thought was great and assumed she would love. I once spent the better part of a year with Elizabeth, when she was married to Richard Burton and we were shooting a film called Ash Wednesday in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy. She said that her publicist had rejected my introduction because there was a story about dog shit in it. I told her that that was true, but that the story was teasing and loving. It was about being as famous as she and Richard then were, like royalty. Maybe I'll use it sometime in the future. We ended up saying that we would get together when I return to L.A. to cover the Robert Blake trial.

Brokaw said David was the Ernie Pyle of his generation.

My five days in Hollywood were a blissful recess from my lawsuit with former congressman Gary Condit and the efforts of Robert Kennedy Jr. to convince the world that I was responsible for the trial and imprisonment of Michael Skakel. There was a long piece in The New York Observer about Kennedy's fight to undo the injustice suffered by his cousin; in the last paragraph the author of the article, Philip Weiss, said that Kennedy was a friend of the editor of the paper. On April 16, both NBC's Dateline and CBS's 48 Hours took up the Skakel case, with the latter devoting a full hour to it.

Robert Kennedy Jr. appeared on both to dispute the guilty verdict. (I was mentioned briefly on the CBS show.) I'm ready to call this overkill, the Kennedy machine at work. Some nice younger brothers of Michael Skakel participated, but Stephen was only nine at the time of the murder, and it's just not enough for any of them to say, "I know my brother didn't do it." The two Skakels who really count in this case did not appear on either show: neither Julie, the older sister, who was very much a part of the events of the night Martha Moxley was killed, as well as a witness at the trial, nor Tommy, the longtime prime suspect, who changed the story he had told to the police right after the murder when he spoke to the private detective agency his father hired to try to shift the blame to Ken Littleton, the tutor in the house on the night of the murder. Tommy Skakel, who was not called as a witness in the trial although he was the last person to be seen with Martha Moxley, is the brother to whom Kennedy has said I owe an apology. If you change your story during a murder investigation, it means either that you lied in the first interview or you lied in the later one. I don't think people who lie in a murder investigation deserve an apology. What would have been interesting in these TV shows would have been to hear what the jurors had to say about the verdict they delivered and how they arrived at it, but no jurors were interviewed.

Shortly after I got back to New York, I was walking into the premiere of Phone Booth, which stars Colin Farrell and was directed by my friend Joel Schumacher, when a television reporter asked me on-camera to make a comment about the embedded journalists covering the war in Iraq. I said how much I admired those journalists, several of whom I know. I singled out David Bloom's incredible you-are-there coverage for NBC. David was always a great reporter. We became friends during the O. J. Simpson civil trial. He was great fun to hang out with, and he kept a group of us in constant hysterics. He loved his NBC cohorts Tom Brokaw and Brian Williams and told wonderful stories about them. He used to show me pictures of his twin daughters, and after our time in L.A. he and his wife, Melanie, had another daughter. He went on to become a White House correspondent, the host of the weekend Today show, and a star embedded journalist on the front lines in the Middle East. I love watching young reporters I meet at trials go up the ladder. The last time I saw David was at a White House Correspondents' Dinner, where we had an O.J. chuckle together. I cried when I heard on the Sunday-morning news on April 6 that he had died the night before in Iraq of an embolism. He was 39. That's young to me, but when you're keeping up with 18- and 20-year-old soldiers and Marines, it's not so young.

David had a magnificent funeral at St. Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in New York. A head of state couldn't have gotten a better send-off. I never saw so many priests on one altar. Being a Catholic, I can say that the service was as High Church as you could get, starting with Cardinal Edward Egan himself saying the Mass, in the presence of Governor George Pataki and former mayor Rudolph Giuliani, as well as every face you've ever seen on NBC News, including Brian Williams, Andrea Mitchell, Katie Couric, Matt Lauer, Tim Russert, Lisa Myers, Jane Pauley, Chris Matthews, and Chip Reid, who was himself just back from the front in Iraq. Incense filled the air. The all-white flowers were perfect, the music triumphant. When David's widow, Melanie, with her three little girls, twins Nicole and Christine, nine, and Ava, three, clinging to her, walked up the aisle, it was a heartbreaking sight. I had never known that David was deeply spiritual, but the service made clear that God was very much a presence in his life. Born a Methodist, he had converted to Catholicism at the time of his marriage. Tom Brokaw said in his eulogy that David was the Ernie Pyle of his generation, that he transformed television war reporting. I wouldn't be surprised if David doesn't become a broadcasting legend. I'll always remember him riding on that tank—the Bloommobile, Brokaw called it—and reporting the war for the liberation of Iraq. He'll always be a hero to me.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now