Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

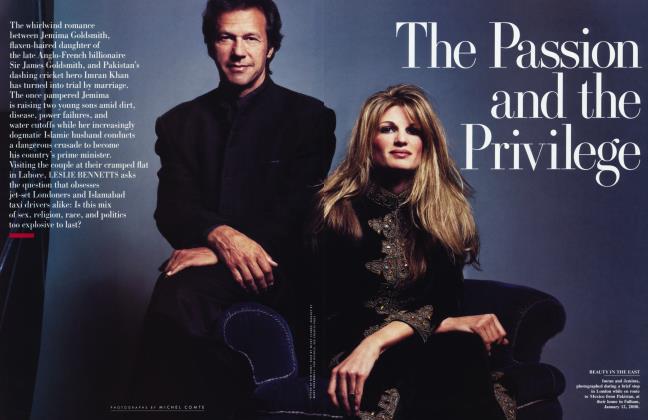

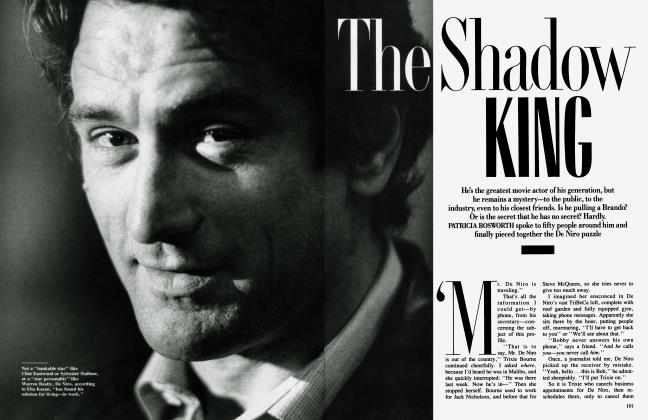

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAt 46, Kim Basinger is one of the world's most beautiful women, mother of an adorable child, and wife of a movie star. But despite her 1997 Oscar for L.A. Confidential, she has not gotten the respect—or the roles—she deserves. With her new movie, I Dreamed of Africa, opening this month, Basinger talks to LESLIE BENNETTS about her volatile relationship with Alec Baldwin, the fears and phobias that have plagued her career, and the eccentricities that prompt her husband to describe her as a character out of Tennessee Williams

May 2000 Leslie BennettsAt 46, Kim Basinger is one of the world's most beautiful women, mother of an adorable child, and wife of a movie star. But despite her 1997 Oscar for L.A. Confidential, she has not gotten the respect—or the roles—she deserves. With her new movie, I Dreamed of Africa, opening this month, Basinger talks to LESLIE BENNETTS about her volatile relationship with Alec Baldwin, the fears and phobias that have plagued her career, and the eccentricities that prompt her husband to describe her as a character out of Tennessee Williams

May 2000 Leslie Bennetts

On a freezing morning at the tail end of winter, with dirty snow still coating the streets, Kim Basinger—a southern girl no matter how many decades she's lived up North—orders iced tea as her breakfast. She has sidled into the coffee shop bundled in her usual disguise—dark coat, hat jammed down over hair yanked back in a ponytail. But when she lets it down and that thick yellow mane swirls across her shoulders, the waiters seem to go into a trance. Iced tea? As she beseeches them with those delphinium-blue eyes, you suspect they would bring her a glass of rubies if that was what the lady wanted.

She is, as usual, about to run for a plane. She has, as usual, been packing. She is, as usual, worried, unsettled, hasn't slept well. She always presents such facts as if they were an anomaly, but the longer you know her, the more you realize they are the constants in her nomadic life. As usual, it has been hellish setting up a time to get together-scheduling a meeting with Basinger is like trying to nail mercury to the wall—but once arrived, she acts as if she has all the time in the world. Hours later, we're still talking languorously when Alec Baldwin, her husband, appears to remind her of her impending flight to Los Angeles. Basinger is supposed to return in a few days with Ireland, their four-year-old daughter. "Did Kim tell you when she's coming back?" demands Baldwin, who clearly finds his quicksilver wife as elusive as everyone else does. "She said Wednesday? Write that down. You're my witness: she's committed to coming back Wednesday. Got that?" He looks sternly at his wife, who smiles vaguely and gazes off into the distance, a dreamy look on her face. You get the feeling that Baldwin had best not spend Wednesday holding his breath.

Basinger has flown into New York to meet Kuki Gallmann, the author of I Dreamed of Africa, an international bestseller about her harrowing experiences in Kenya. Published in 1991, the book has sold two million copies in 15 languages, but for years Gallmann turned down movie proposals because the events she related in her story were so tragic she couldn't bear to relive them. When Gallmann finally agreed to a film directed by Hugh Hudson, Basinger was cast in the starring role, opposite Vincent Perez. Now Gallmann has finally seen the film—"I cried for two hours," she admits—and bestowed her approval on the actress who worked so hard to portray her authentically. "Kim was very genuine," says Gallmann, a handsome silver-haired 56-year-old. "She put her heart into it. She's so beautiful and glamorous, but she opted for truth. She had to be so disheveled and tired, with puffy eyes all red. She didn't hold anything back."

The rigors of the role were daunting indeed. Exhilarated by passion and the sense of unlimited possibilities, Gallmann and her husband moved from Venice to Kenya in 1972 to establish a farm, but paradise exacted an unbearable price. The author eventually lost her mate to a car crash and her son to the lethal bite of a puff adder. From the euphoria of love and lust to the ultimate tragedies of grief and senseless loss, Gallmann's story ran the gamut. "There's not an emotion I didn't get to play in this movie," says Basinger. "This was the biggest challenge I've ever had in my life, as an actress. I've never really gotten an opportunity like this, to be handed this much responsibility. You sink or swim in this one."

Her admirers believe this will be a breakthrough film for Basinger, even more than L.A. Confidential, for which she won an Academy Award as best supporting actress. Basinger's acting career has already spanned nearly 30 years, and her leading men have included Sean Connery in Never Say Never Again, Richard Gere in No Mercy and Final Analysis, Robert Redford in The Natural, Jeff Bridges in Nadine, Burt Reynolds in The Man Who Loved Women, Mickey Rourke in Nine 1/2 Weeks, Sam Shepard in Fool for Love, Michael Keaton and Jack Nicholson in Batman, Val Kilmer in The Real McCoy, Bruce Willis in Blind Date, and Alec Baldwin in The Marrying Man and The Getaway—not a bad lineup by any measure.

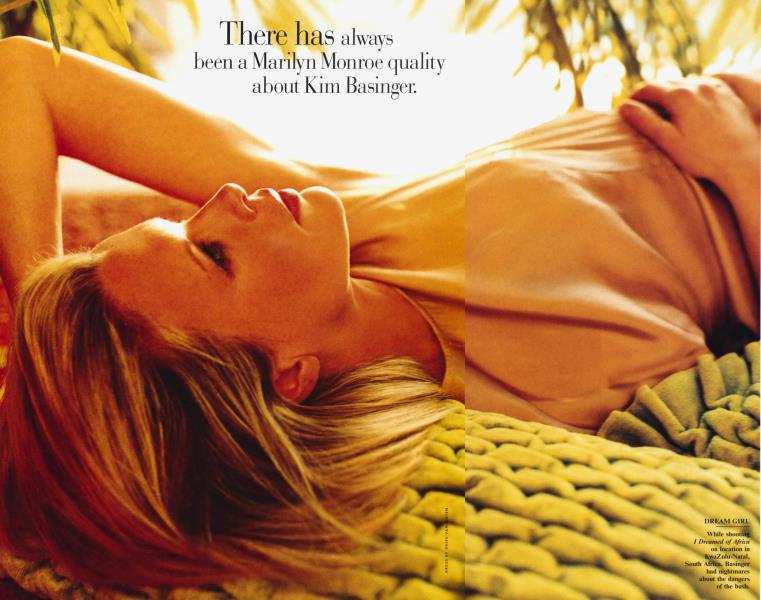

There has always been a Marilyn Monroe quality about Kim Basinger.

But her career has also been punctuated by more than her share of bizarre missteps and bad word of mouth, and some observers feel Basinger—despite the fact that she makes $5 million per picture—has never enjoyed the stature she deserves. I Dreamed of Africa may change all that. "I think you'll be surprised," says Hudson, who also directed Chariots of Fire and Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes. "You are going to see a different Kim. You don't expect her to play this kind of role with such strength and fortitude and passion, and to hold a film like this together. But she was obviously ripe and ready for a central role. They're very rare for women, and in this one she's literally on-screen in every single scene. And she moves you. She completely succeeded. She'll be put up in the category of those great screen actresses, the three or four of them. Nobody would have expected her to be categorized with Glenn and Meryl, but I think she will after this. She's become a great actress."

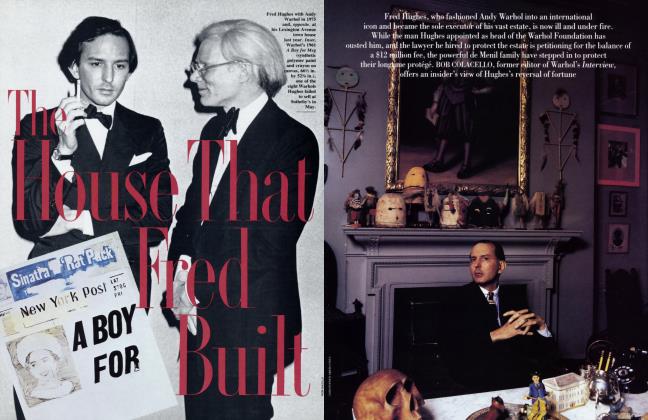

DREAM GIRL While shooting I Dreamed of Africa on location in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Basinger had nightmares about the dangers of the bush.

DREAM GIRL While shooting I Dreamed of Africa on location in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, Basinger had nightmares about the dangers of the bush.

At 46, Basinger also remains a great beauty. Her luminous face is as fresh as a baby's; nary a wrinkle mars that alabaster skin, an eloquent testimonial to the wisdom of avoiding the sun, which she does with fanatical determination. But in Africa the brutal sun was only one of many problems. For Basinger, making a movie in South Africa's remote KwaZulu-Natal, where the film was shot, meant conquering stark terror. Overwhelming fears have ruled her life ever since she was a child, when her mother had to ask the teacher not to call on her: "She'll faint!" (The only time a teacher did call on Kim, she got dizzy, blanked out, was jeered by her classmates, and ran from the room in a panic.) Nor did her demons subside with adulthood; a longtime agoraphobic, Basinger was once housebound for six months. But for a mother whose child was still a toddler when the movie was filmed, spending three months in Africa meant scaling the Mount Everest of fear.

"I knew I had to do this," Basinger says. "Kuki Gallmann is a conservationist, heavy into the environment and animal protection, which is a huge subject of mine. Here was a woman who faced her fears. But there I was, rolling over at 2:30 in the morning, breaking out in tears. Alec would say, 'It's O.K.; you have to do this.' But I didn't know a thing about going into the bush. Here I am, taking my three-year-old to an area with the highest rate of AIDS in the world, where there's all this disease and political instability, where even the bare necessities like clean water are questionable. There's the tick fever the crew came down with, where you have sores this big ..." She spreads her hands wide. "And everything in Africa has teeth: the trees, the bushes—everything is a potential danger for a three-year-old child. There are puff adders, spitting cobras, pythons the size you wouldn't believe, poisonous frogs— you have no idea the dreams I had at night. So vivid and terrifying!"

She closes her eyes and shudders. "Alec and I love adventure; I'm not afraid of a little rain, a little mud, wearing the same clothes for a couple of weeks. But taking my child to Africa—that was my horror. I didn't know whether I'd get through it emotionally."

But she did, triumphantly. The movie is lush and gorgeous, portraying an Africa so ravishing it's easy to understand why both Kuki Gallmann and, many years later, Basinger herself fell in love with it. Africa turned out to be one of the best experiences she's ever had.

It's real life that's hard.

Last spring, on a brilliant June day, Basinger and I had lounged on the screened-in porch of her vast country house in Amagansett, discussing the perennial topic of where she should live. (We had been discussing it for six months already, but I hadn't yet figured out that this uncertainty was a permanent condition rather than a transitional problem.) The setting was idyllic. As sun-dappled shadows rippled across the emerald lawn, a balmy breeze rustled ceaselessly through the treetops, which sighed and tossed in constant motion. Thoroughbred horses grazed in the meadows around us, and just visible through the leaves was the gabled roof of the house where Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller retreated during their brief, tortured marriage. Suddenly, Basinger leapt to her feet, squealing and hyperventilating.

A deer had emerged from the bushes and was trotting calmly around the swimming pool. Basinger watched, transfixed, as the doe peered quizzically at us and then darted through an opening in the hedge. "Ohhhh!" She sank back into her wicker chair, her face suffused with bliss, and exhaled slowly. For a moment the only sound was the twittering of birds. "Maybe we can make it work here," she said. "I'm willing to give it a try."

"Kim is extremely uncomfortable in the spotlight," says director Curtis Hanson. "And she's mercurial. She's kind of like quicksilver."

For months Basinger and Baldwin had been fighting about where to live now that their daughter was ready to start school. They had always shuttled back and forth between Basinger's small bachelor-girl house in Los Angeles, the Manhattan apartment they share on Central Park West, and this palatial spread in the Hamptons. Baldwin wanted to make the country their primary residence, but Basinger had agonized endlessly. Would it be too isolating? Could she be happy here? Would she turn into a suburban housewife? After Ireland was born, Basinger sank deep into what she now refers to as her "June Cleaver phase" ("Say bye-bye to Daddy!" she coos, mocking herself in a baby voice), devoting all her attention to the child who seemed such a miracle to her 41-year-old mother. Even when Basinger was offered the irresistible part of Lynn Bracken, the sultry call girl who epitomizes old-fashioned Hollywood glamour in L.A. Confidential, she turned it down twice ("I should have my butt kicked," she says now) before reluctantly accepting the role that would win her a Golden Globe and a Screen Actors Guild Award along with her Oscar.

But as her career heated up again, so did the attendant complications. By last spring Basinger had agreed to enroll Ireland in school in the Hamptons, but when September arrived they were stuck in Toronto, where Basinger was filming a thriller called Bless the Child, to be released this fall. The new year brought a new round of promises to get Ireland into school. "Next week," Kim said in February. "Or the week after ..."

They have owned the Amagansett place for nearly four years, but it still looks as if they moved in a few days ago; the whole house is piled to the rafters with packing crates and furniture shrouded in bubble wrap and quilted moving pads. There are spiderwebs everywhere; not one room is usable, so when they come out here they stay at a nearby inn or in a rented house instead of their own spectacular estate. The idea of actually making this place into a home seems to overwhelm Basinger. She keeps coming to the house and sitting on the porch, contemplating the enormity of the task before her—and leaving it exactly as it is. (She now claims that Alec hired the deer that appeared before us so enticingly on that long-ago day last spring, just to seduce his animal-loving wife into settling down there.)

"Alec is someone who longs for normality," Basinger says with a sigh. "But I'm a gypsy at heart. I'd take off in a minute and go live in France for a year. I'd go live in Africa. But Alec is obstinate. He's got his mind set on living this life out on Long Island. He wants geese overhead. He wants what he perceives as a fairy tale. But it's a two-and-a-half-hour drive to New York City to have a meeting, and that's the reality. I love the fairy-tale magic of it all, but I'm going to see ... "

Then she smiles, her face lighting up with a new thought. "I'm not going to worry about this, because this is just a onetime thing," she says. "I can always change it. There's tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow to worry about."

Scarlett O'Hara may be the first character who comes to mind, but Basinger's husband says the reality is more like something out of Tennessee Williams. "The reason I fell in love with Kim is that she's so odd," Baldwin says. "With that kind of beauty, this is a woman who could have married the head of a studio or a big director or a movie star who gets $20 million a movie. She could have everyone shining her ass 24 hours a day. She could have played ball. But she's a very odd woman. I've done plays by Tennessee Williams; he was really able to enunciate certain southern characters. I'm from Long Island—I never really knew they existed. But my wife is one of those people—an absolutely maddeningly peculiar, exotic, lovely person."

Indeed, spending time with Kim can reveal an unpredictable cast of characters. One day she seems quite straightforward; the conversation is logical and linear. Another day she seems to be on another planet; every question sends her off on long digressions and mystifying free associations filled with sentence fragments that trail off into vapor. On one particular afternoon, she is distracted and short of sleep; she and Alec had a fight the night before and she's still fuming. We are hanging out in a small office Alec keeps on the ground floor of their Manhattan apartment building, filled with massive masculine furniture and free weights lined up in a perfect row in front of a huge bank of television and stereo equipment. (Kim refers to this room as "the dungeon") When Alec walks in, Kim lets him have it, immediately picking up their argument where they left off. (Alec broke his promise not to make business calls while driving the family in from Long Island; when he lost his temper on the phone, the car swerved dangerously.) "Why did you break your promise?" Kim demands, as furious as if Baldwin had abandoned her for another woman.

Volatile as their relationship is, it has clearly provided a crucial anchor for her. "Kim has changed a lot," says her youngest sister, Ashley Brewer, whom Basinger considers her best friend. "She is so much happier now. She absolutely adores being a mother, and she's real safe and secure in her marriage. She and Alec just constantly disagree ... but they love each other very much, and they'll be together forever."

Fighting all the way, no doubt. "He'll look at me and say, 'I hate you, you know,"' Basinger reports with a mischievous grin. "I'll say, 'I hate you back.'"

If anything, Basinger has often seemed even more eccentric in public than she does in private. There was her unfathomable decision to buy the town of Braselton, Georgia, a business venture that involved her brother and became such a fiasco that it caused a major rupture in her family. (Basinger didn't speak to her mother, whom she once worshiped but who sided with her brother, for nine years.) There was her romance with Prince (Prince!), who seemed an exceedingly unlikely choice for the ultimate prom queen. There was her catastrophic commitment to star in Boxing Helena, a repellent movie in which Basinger would have played a woman whose arms and legs are cut off by a former lover who keeps her in a box. When she backed out of the project, the production company sued her. Basinger lost the court fight and was forced into bankruptcy.

The periodic eruptions of bizarreness also included Basinger's disastrous 1990 appearance as an Academy Award presenter, specifically the grotesque gown she designed herself, to universal ridicule, and the impromptu outburst that stunned the most important show-business audience in the world. (As Baldwin describes it, "There's Kim standing up there saying, 'You idiots should have given an Oscar to Spike Lee—shame on you!'")

"She really stuck her foot in her mouth that time," says Brewer. "But she has a huge heart, and she just says what she believes."

When I ask Basinger about the weirdness factor, she throws her head back and whoops with laughter. She laughs for a long, long time—and doesn't explain it at all.

"There are a number of things she's done that flout expectations," Baldwin tells me later. "She doesn't care. There's this innocent foundation that's always linked to passion: 'I loved it when my mother made me dresses, so I'm going to make my own dress for the Oscars.' 'I love music, so I'm going to date Prince.' It's completely fueled by emotion. Kim is an extraordinarily instinctual person."

Baldwin does his best to accommodate her capriciousness, although it can be exasperating. She refused to deal with furnishing their New York apartment, so he hired a decorator and got it done. "She said the whole thing looked like Nancy Reagan's bedroom," reports Brewer. Basinger never bothered with pool furniture, so Baldwin bought some—only to be greeted by shrieks of "I hate it! Take it back!"

He should have known. Basinger, who has enough dogs to open her own pound and feeds every stray cat for miles, fell in love with Baldwin the morning they were driving down the Hollywood Freeway to the set of The Marrying Man and saw a dog get hit by a car and run off, injured. To Baldwin's astonishment, she insisted he chase the dog so they could take it to the vet— which he did, risking his life and causing them both to be extremely late to work.

But he got the dog—and the girl.

"She wants you to get out of the car and get the dog on the Hollywood Freeway, so you jump out of the car and get the dog," he says. "You carry 16 bags to the airport because she wants chopped almonds on the plane. She doesn't want diamonds and furs and penthouses; she wants chopped almonds. It's 20 degrees below zero, but if Kim wants vegetable soup from the blah-blah diner, I put on my boots and go get it, because I love Kim. Kim's tastes are very simple, but she doesn't want any of the things anybody else wants."

Her emotions are endlessly volatile. Baldwin will be awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of his wife weeping; when he asks her what's wrong, she sobs that she wishes she had finished college. He arises in the morning to find her sitting with a fist in her mouth and a look of horror on her face, tears streaming down her cheeks as she watches the television news: "Alec, we've just got to do something about the Albanian refugees!"

There seems to be a bottomless reservoir of empathy and grief inside her. Almost anything can elicit the pain, which easily overwhelms her. It is doubtless the source of her longtime commitment as an animal-rights activist; Basinger, who has few friends and rarely goes out, identifies far more easily with animals than with people. She will always give her heart to the wounded rather than the whole. "If you walk into a field of perfect pumpkins, she walks over to the hideously deformed pumpkin and takes that one," reports Baldwin. "She says, 'You know I'm always going to pick the ugly one no one else is going to want.'"

There has always been a Marilyn Monroe quality about Basinger; one gets the sense of someone permanently bruised, profoundly damaged—but by what? Like Basinger herself, the answer is peculiarly elusive. She grew up in Athens, Georgia, as the middle child of five. She adores her father and says she'll love her mother "forever," despite their rift, which they have recently begun to mend. Her parents eventually separated, but they have never divorced. "Southern people don't get divorced; they just separate for 20 years," Basinger says. "They live about two miles from each other."

Kim was a shy, introverted girl who was often "flat-out paralyzed by fear and selfconsciousness," she says. But she is vague about the underlying reason for her fears. "Parents can be very influential in designing those little creepy-crawlers that jump around in your mind for the rest of your life," she says darkly. "It's the fear of not being good enough. Someone somewhere along the way has given you the idea that maybe you might not be."

In retrospect, she feels her mother's attempts to shield her—by calling the teacher, for example—were misguided. "She was a mother tiger; she thought she was protecting me, whereas in reality I needed help," Basinger says. "That was a sign of something that was definitely wrong."

But even then she was strong-willed. "Kim refused to eat meat," says Brewer, who still lives in Athens, as do their parents. "My mother would send her to her room. That was a war right there." As stubbornly devoted to her principles then as she is today, Basinger never gave in. She still doesn't eat meat.

Her beauty was another cause for inner turmoil. Her peers failed to recognize it, tormenting her about her height and the voluptuous lips that would later make men weak-kneed. In the Deep South of the 1950s, she was taunted with names such as "Nigger Lips" and "Tall Tree." When she was only four or five, Basinger told her father she wanted an operation on her mouth. "My father would say, 'Someday you're going to make money with those lips,'" she recalls. But by high school she had become a varsity cheerleader and "the kind of girl that 15 guys asked to the prom," as Brewer puts it. "There were too many girls who were jealous of her, who hated her."

The Athens Junior Miss pageant was Basinger's ticket out of Georgia, but despite considerable success she loathed being a model. "I was so insecure I was out of my mind," she says. "You're just criticized all the time. O.K., so that fried me. And I was fighting my own image tooth and nail every day. I rebelled against it. I don't consider myself sexy. I have to act to be sexy. I'm not very good at being a 'girl,' for the type of man who loves that kind of thing. I'm a clean person; I'll put on a little makeup, but I'm basically not a very feminine girl."

Her habitual uniform is what her husband calls the "Chairman Mao outfit"—white T-shirt, black pants, black socks, no frills—hardly a getup for the kind of sex symbol she has generally played. Mustering that inner femme fatale has always required an enormous effort. When she first came to New York, the venerable Eileen Ford even let Basinger stay in her house for a while, but the fledgling model spent most of her time locked in her room reading the Bible. "I was so scared of my own shadow that it was difficult for me to cross the street at all, my heart was beating so badly," Basinger says. "I felt like 'Whatever you do, please don't look at me!' All these eyes are on you, and I don't want 'em on me." She rolls her eyes. "Am I in the wrong business or what?"

Seeking some form of protection, she married Ron Britton, a makeup artist 16 years her senior, whom she describes as "a father figure." They divorced after eight years, and Basinger spent the next eight years paying him alimony.

Nor did her career provide much of an anchor. "People are so fickle," Basinger says wearily. "This business is so fickle. I know what it feels like to be on the absolute bottom—emotionally, spiritually, professionally—to be absolutely naked down there, and then to get up and start rising, one step at a time. I've learned a lot of things the hard way. God knows I've done things I wish I'd never done. But I've been very lucky to learn those lessons. A lot of this has strengthened me, freed me. There's always something to learn. Everyone loves a winner; it validates you to a society that gives you all those ribbons and awards. But success is like wildfire: they throw a little of it your way ..." She sighs.

Basinger knows all too well what it's like when "they" stamp out the fire. After meeting Baldwin a decade ago on The Marrying Man, she and her husband-to-be had a horrendous time making the movie; the stars ended up virtually at war with the Disney executives overseeing the film. Basinger became the target of venomous rumormongering that charged her with being chronically late, with demanding tanks of Evian water for her shampoos (completely untrue, she insists), with vanishing into her trailer for torrid sessions with Baldwin. She was also excoriated for asking that some of Neil Simon's lines be rewritten; she believed they were misogynistic and unfunny. Although critics have had the same problem with Simon's female characters for years, the male studio executives on The Marrying Man were as outraged as if a bimbo had had the temerity to question God. (Basinger's instincts were later confirmed by the critical pounding the film received—and by its failure at the box office.)

Although the experience put a serious dent in Basinger's professional reputation, intrepid directors have not been deterred. "I heard stories about her and Alec going a bit wild back then, but they had just met each other—why wouldn't they go a bit berserk?" Hugh Hudson says. "Having read the things people had said about her, I expected it to be more difficult, but I enjoyed working with her very much. I did not at any moment find her a prima donna."

Curtis Hanson, the director and co-scriptwriter of L.A. Confidential, was equally pleased. "I've always felt Kim has been underappreciated, that she was a better actress than the material she was in," he says. "Kim is candid: that's the good news, and that's the bad news. I don't think she's good at being politic. But once we got past the questioning, she gave herself over to trusting me, and the result was an apparently effortless performance and a complete lack of self-consciousness. Even though she is not on-screen that much, she is so emotionally true that she dominates the movie.

"But Kim is eccentric, and she's mercurial. She is just such a contradiction. She's beautiful, and yet she does her best to reject it. She's tomboyish. She's funny; she made me laugh a lot. Most actors crave the spotlight; they love the attention. Kim is extremely uncomfortable in the spotlight. She genuinely hates it."

Indeed, Basinger's peak moment in the spotlight turned out to be so stressful it completely short-circuited her wiring. When she was nominated for an Academy Award for L A. Confidential, she expected to lose to Gloria Stuart. "Everyone said Titanic would take everything," she explains. "I never imagined I would get it. The Academy Award is out there in space—Cinderella and the pumpkin and the whole nine yards. When my hairdresser asked me if I'd prepared a speech, I told her, 'I don't have anything. You know and I know it's Gloria.' I was all ready to stand up for Gloria—and then Cuba Gooding turned to me and said my name, and everything went silent. Everything was in slow motion. My whole brain switched off. Alec was mouthing, 'Get up! Get up!' But I had no thought process. I know God helped me out of that chair."

She made her way to the stage in a daze. "My dress had this pain-in-the-ass train, and the cameras are up your nose," she says. "I don't remember anything. I just remember holding up the Oscar and saying, 'This is for you, Daddy!' The Oscar was wet and it was slipping out of my hand; and I remember looking down all of a sudden and I saw the actual thing in my hand and I thought, 'Uh—did I steal this from the bathroom?' I'm still in shock to this day."

But if the spotlight remains torture for her, the experience of submerging herself in motherhood has taught Basinger a lesson about the dangers of retreating. "I don't want to be dependent on my daughter emotionally," she says. "That's not a good thing for your child to see. You have to be content in your own accomplishments and live life in a balanced emotional state, rather than living as someone who's indecisive, who's needy, who's emotionally all over the place."

Basinger has always believed that separation issues were part of the problem with her own mother, and the complexities of their relationship provide a cautionary example in charting her own course. "Kim has vowed not to do what her mother did," Baldwin explains. "She keeps reminding herself that your child is going to grow up and leave you, so you have to make sure you have a life for yourself."

Where that life will be is anybody's guess, but it's likely that Baldwin's attempts to turn a Tennessee Williams character into a soccer mom will be thwarted, one way or another. Basinger has more pressing matters on her mind than decorating a big house. In the past, she has often compared her life to a battered old trunk: everywhere it's traveled, someone has slapped a sticker on it, and now it's covered with other people's labels. She sees her personal goal as stripping off all those old labels and discovering what's underneath.

"I still haven't gotten to the core of who I am and what I want to do in my life," she says. "It's like I've got a garden, and it's got a lot of weeds; things need to be done to it, but it has a lot of potential to be reborn. As much as I've loved doing for my child, I need to get back there."

There is a faraway look on her face as she gazes off into the distance. "Becoming the person I'm meant to become," she says softly. "That's all I want."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now