Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Passion and the Privilege

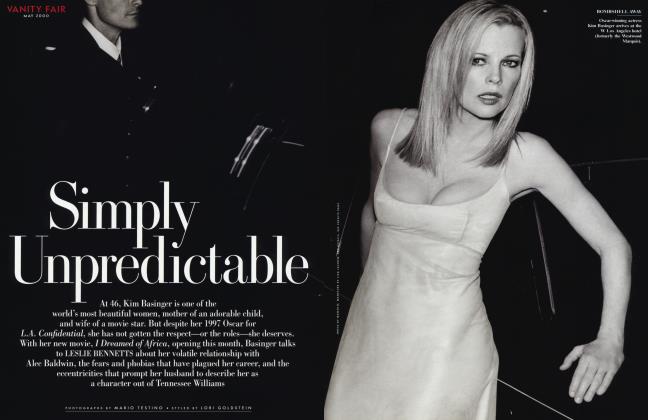

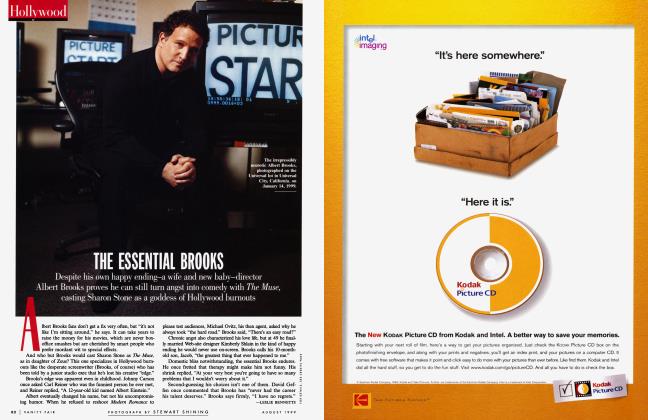

The whirlwind romance between Jemima Goldsmith, flaxen-haired daughter of the late Anglo-French billionaire Sir James Goldsmith, and Pakistan's dashing cricket hero Imran Khan has turned into trial by marriage. The once pampered Jemima is raising two young sons amid dirt, disease, power failures, and water cutoffs while her increasingly dogmatic Islamic husband conducts a dangerous crusade to become his country's prime minister. Visiting the couple at their cramped flat in Lahore. LESLIE BENNETTS asks the question that obsesses jet-set Londoners and Islamabad taxi drivers alike: Is this mix of sex, religion, race, and politics too explosive to last?

LESLIE BENNETTS

"I went into this marriage wholeheartedly, and my hope is that it will work" Jemima says.

Jemima and Imran Khan are already late for Sunday lunch at a friend's horse farm an hour outside of town, but Jemima can't get dressed. Her long honey-colored hair is greasy and tangled, and although it's past noon she's still in a bathrobe. "I don't have any conditioner, so I put coconut oil on my hair before I wash it, but I can't have a bath, because there's been no water all morning," she says. The children have both been ill; the three-year-old has diarrhea, and the baby is wailing in the next room. She can't feed him, because there's no electricity to puree his food. Her husband is so exasperated he looks as if he were about to implode. "Go without me," Jemima urges. "I'll come along as soon as the water goes back on."

And so Imran leaves without her for the long, dusty drive out of Lahore, through streets teeming with motorized rickshaws and ancient, rusted cars, cattle and goats, donkey carts laden with bananas, limbless beggars beseeching passersby, and robed women kneeling beside roadside canals to wash their clothes in the filthy, muddy water. (The morning paper contained the usual news of dead bodies found floating in the canals.)

Out in the countryside, the farm is a beautiful estate where friends are already lounging on a manicured lawn, awaiting the Khans. Although the group includes several past and present cricket stars, along with the scions of various wealthy families, as always Imran—the legendary captain of the Pakistani cricket team who led his side to victory in the 1992 World Cup—is the tallest, the handsomest, the most charismatic. Proud and erect, he seems a natural aristocrat even among his peers in Pakistan's ruling elite.

Mollified by a leisurely lunch proffered by silent servants at a long table set with immaculate linens, crystal, and silver, Imran relaxes slightly, although even in a relaxed state he seems coiled tight as a spring. When Jemima calls at four o'clock to say she's on her way, he tells her curtly not to bother. By the time we get back into the city, it's dark and Jemima is waiting with freshly washed hair, her elegant body swathed in a shalwar kameez, the long Pakistani tunic and pants that cover a woman's arms and legs as prescribed by Islamic law.

She looks ravishing, of course. Tall, fine-boned, and slender as a greyhound, Jemima Khan would look exquisite in a gunnysack. But everything about her circumstances seems impossibly incongruous, starting with the fact that she lives in Lahore. "The city from hell," as one of her closest British friends describes it, Lahore is a Third World nightmare of overpopulation, desperate poverty, and a choking haze of air pollution that hangs so heavy you feel as if you were breathing pea soup. Jemima doesn't even live in the kind of insulated luxury enjoyed by her friends on the horse farm. Her own apartment consists of three small, dilapidated rooms in her elderly father-in-law's modest red-brick house, which is also occupied by one of Imran's sisters, her husband, and their three children, along with a rotating assortment of other family members. Traffic rumbles ceaselessly outside, spewing exhaust fumes to a constant chorus of beeping motorbikes; chickens scratch in the dirt yard; laundry hangs forlornly on a clothesline in front of the living-room window. Jemima doesn't even have a washing machine to clean her children's soiled clothes.

None of this would be noteworthy if Jemima were someone else. But as the daughter of Sir James Goldsmith, the late British billionaire, and his wife, Lady Annabel, who comes from one of England's most august aristocratic families, Jemima is an extraordinarily privileged young woman. When she fell in love with Imran Khan and dropped out of Bristol University to marry him, it seemed like a fairy tale. With her masses of tawny hair and amber-colored eyes, Jemima was the ultimate golden girl, and Imran—an Oxford-educated sports hero and a notorious international playboy who had left a trail of broken hearts on several continents—appeared to be the quintessentially dashing Prince Charming, even if he was twice her age and she had to convert to Islam in order to live happily ever after.

In June of 1995, her parents gave them a lavish wedding reception at Ormeley Lodge, their 18th-century Queen Anne-style mansion outside London. The celebration was attended by luminaries who ranged from Henry Kissinger, Sir David Frost, Princess Michael of Kent, Elle Macpherson, and Jerry Hall to Claus von Biilow, with Mark Shand, Camilla Parker Bowles's brother, serving as Imran's best man. As the newlyweds took off for a honeymoon at the Goldsmith estate in the mountains outside Marbella, they seemed a dazzling match. (This impression was only enhanced by the subsequent paparazzi photographs taken with a telephoto lens of their nude lovemaking on a sundrenched terrace. "The most amazingly sexy pictures," says one unrepentant voyeur who saw the shots, which were widely circulated in London. "A disgraceful intrusion, but you thought, Oh, what a beautiful couple!")

But the story of Jemima and Imran had only just begun, and five years later much has changed. Their marriage has already survived the arrival of their own two children as well as an explosive paternity suit brought by the mother of Imran's highly inconvenient love child, along with criminal charges filed against Jemima for smuggling, the relentless hounding of England's tabloid press, and the ongoing turmoil in Pakistan, where a military coup overthrew the democratically elected government last fall. The already heady mix of sex, scandal, religion, race, and fabulous wealth has been spiked with a growing portion of politics, and it's high-stakes politics indeed.

Imran would like to be Pakistan's next prime minister, and he has formed a political party that consumes an increasing amount of his time and attention. As Jemima points out, the South Asian subcontinent is a place where political leaders tend to meet untimely ends, and the risk of assassination can't be dismissed in a country where the last prime minister has been accused of trying to kill off the army chief now in charge by denying his plane permission to land, even though it was running out of fuel. (General Pervez Musharraf, who is currently in control of Pakistan and its 140 million people, managed to land the plane and overthrow the prime minister instead.) The country's nuclear standoff with India, the constant hostilities generated by the ongoing dispute over Kashmir, and the spillover of terrorist elements from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan were among many reasons Time magazine recently declared the region "one of the most dangerous places on earth."

Imran, who says his phones have been bugged for years, has already been the target of political enemies who bombed the cancer hospital he founded, even though the hospital provides free care to destitute patients who would otherwise be unable to obtain such specialized treatment. The blast killed 8 people and injured 30, but Imran, who was supposed to be touring wards at the time, hadn't arrived and wasn't hurt.

Jemima was the ultimate golden girl, and Imran appeared to be the quintessential^ dashing Prince Charming.

He has long been a national hero, and his commitment to charitable care has only burnished the movie-star luster of his reputation at home. But whether Imran's already strained marriage will survive the rigors of a political career and his simplistic espousal of Islamic dogma is a question that has generated much speculation at elegant dinner tables. (As Imran's friends have pointed out, fathering an illegitimate child in Pakistan, an Islamic state, not only disqualifies a man from public office but can be punished with death by stoning, as can adultery.) From Islamabad to London to Beverly Hills, an eclectic crowd of riveted observers—from international diplomats to titled aristocrats, British tycoons to Pakistani taxi drivers—follows the saga of Imran and Jemima as if it were a juicy soap opera.

No one who knows them would be foolish enough to put money on how it will turn out.

hen Imran Khan strides into Lahore's Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, which he named after his mother, it is as if an electric current had surged through the crowd of people waiting patiently to be seen. Even wearing sweatpants, running shoes, and a green polo shirt with the shirttails out, he looks regal, towering over the rest of the men. The marble-floored lobby is filled with bald, sad-eyed children and people in wheelchairs. Veiled and shrouded, the women never take their eyes off Imran; the men reach out to touch him as reverently as if he were a god. Eyes filled with tears, they tell him how grateful they are for what he has done. Imran nods and moves on. Despite his characteristic aloof detachment, he understands all too well what it's like to stand by helplessly while a loved one dies an excruciating death, as his mother did from colon cancer in 1985 at the age of 63. The experience galvanized him.

"I didn't know what a cancer hospital was," Imran says in his cultivated baritone. "I just jumped into the deep. The idea came from an incident that happened while my mother was in a lot of pain. I was waiting to see a doctor, and this man came in, disheveled, and asked, 'Have I got these medicines?' They said, 'No, you still have to buy this one.' He just broke down. He didn't have the money. His brother was dying of cancer; he had brought him from a village 100 miles away. He was just lying in the corridor."

Imran has already described to me in hideous detail what the existing Pakistani hospitals he had seen were like: rats running around the wards, four or five people to one bed, sheets black with filth, cats prowling the intensive-care unit—a stark contrast to the clean, modern hospital he was inspired to build. "When you grow up in this part of the world, you see so much misery you develop an immunity, but being very vulnerable myself at that moment, I thought, I must do something," Imran explains. "From then on it was in my mind all the time. Whoever I asked said, 'You can't build a cancer hospital. The equipment is very expensive, the running costs are so high, and your idea of treating poor patients for free—it's impossible, the drugs are too expensive.' All the educated classes kept saying, 'You're just a dreamer, it's not going to happen.'"

But Imran refused to give up, and in 1991 he broke ground for the hospital, which opened in 1994 after a last-minute popular appeal. "We were short $4 million, so I got in an open van with a big box and went around Pakistan to 30 cities, collecting money," says Imran, who was the largest single donor until recently. "I'd start at seven in the morning, and at midnight people would still be giving me money. When it opened, that was the greatest feeling of satisfaction and happiness I'd ever known. God was kind to me in cricket, but nothing came close to this."

CONTINUED ON PAGE 218

Imrans commitment to charitable care has only burnished the movie-star luster of his reputation at home.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 190

At 47, Imran has been retired from sports for 8 years, but he enjoyed one of the longest professional careers in cricket history, playing from the age of 18 to 39. He was renowned as an all-rounder, a fast bowler who was also proficient at bat, and as an inspirational captain who took on a Pakistani cricket system mired in nepotism and corruption and engineered Pakistan's emergence as a force in world cricket.

But because of his personal attributes, Imran's fame transcended the sports world and elevated him into international society at its most rarefied levels. "He wasn't like a Wayne Gretzky with broken teeth; the thing about Imran was that he was just so fucking beautiful," says one Oxford schoolmate. "There's no real equivalent in American sports, although Michael Jordan might come close in some ways. Imran had natural class; people would defer to him. He was so arrogant and beautiful that even arrogant and beautiful people could not cope with him; you look at him and you feel inadequate." Indeed, cricket insiders tell stories about how Imran's physique was so astounding that when Pakistan was playing its arch-rival, India, Imran had only to walk through the locker room naked to intimidate the other team.

Even now his taut body betrays not an ounce of flab, and with his chiseled features, bronze skin, and tousled black hair, Imran cut quite a swath through London social circles during his years as a player. "He was very glamorous," says Lady Cosima Somerset, Jemima's cousin. "Lots of women were in love with him."

"I think I was one of the few upper-class English girls he hadn't got in bed," jokes Jemima's older half-sister India Jane Birley, a painter. Imran's lady friends included Goldie Hawn, the artist Emma Sergeant, actress Stephanie Beacham, heiress Susannah Constantine, Lady Liza Campbell (daughter of the Thane of Cawdor), and German MTV presenter Kristiane Backer, along with many others (one of whom described him as "sex on a stick"). Certainly his exoticism lent him an aura that palefaced Englishmen found it difficult to compete with. "Women flung themselves at him like lemmings going off a cliff," observes his friend Jonathan Mermagen, a sports marketing consultant. "Young titled women from good English families—they behaved like 15-year-olds around David Bowie."

But Imran was always more than an athlete. He has written five books, including Warrior Race, a lavishly illustrated volume about the Pathan tribes of Pakistan's North-West Frontier province, and Indus Journey, which traces the great Indus River from its delta on the Arabian Sea to the headwaters in the Himalayas. An autobiography called Imran Khan: A Political and Spiritual Memoir is being published by Macmillan in England next year.

Pakistan is a country of tribes, and Imran, the son of an engineer, is a descendant of the infamous Pathan warriors from the wild, remote region called the Tribal Areas. The Khans were the landowning tribal chieftains; "Khan" means prince. Proud and fiercely independent, the Pathans have long been renowned as men who cannot be tamed. "No one has ever managed to subdue them," notes one Pakistan guidebook. "The Mughals, Afghans, Sikhs, British and Russians have suffered defeat at their hands."

Like his ancestors, Imran has always been a man who refuses to give up, and he has an impressive track record of triumphing over impossible odds. When he became captain of the Pakistani cricket team, he was recognized as a lethal player. But few anticipated the remarkable leadership ability that would allow him to drive a less-than-stellar group of men to the most unlikely victories. Imran doesn't play to lose.

These days his foray into politics is eliciting similar predictions of failure from the powers that be. One night Imran, Jemima, and I go to a dinner in Lahore for William Milam, the American ambassador to Pakistan, a jovial man with shrewd eyes. When I ask Ambassador Milam how much chance he thinks Imran has of becoming prime minister, he laughs heartily. "Zero," he says.

Meanwhile, Imran has taken one look at the crowd and regrets having come. The party is thronged with the Pakistani ruling elite, notably supporters of the last two democratically elected governments, those of Benazir Bhutto (a schoolmate of Imran's at Oxford) and the recently deposed Nawaz Sharif—both of whom have been accused of corruption on a staggering scale. If Imran were a different kind of man, he might circulate and schmooze, cultivating support even among those he holds in contempt. Instead he wolfs down a plate of lamb, rice, and chicken curry at the buffet and signals to Jemima that he wants to leave immediately. "There were so many crooks there," he says in a loud voice as we depart.

Since Pakistan is ranked one of the most corrupt states in the world by international risk-assessment experts, a candidate offering probity has his work cut out for him. Although Imran's detractors suggest that he simply can't stand being out of the limelight and sees politics as a way back in, his determination to help his country seems motivated largely by altruism, since it's obvious that he could have a much more pleasant life as the husband of an heiress in England. "I'm basically an idealist," he says. "I've never been a realist in my life. It was like that in cricket. I never thought I could fail."

He is also too proud to be supported by his wife. "He would rather die," Jemima says. "He believes in a man being able to support his family. But he gave most of the money he'd made in cricket to the hospital. He has given everything that meant anything to him, including his Mercedes, his World Cup, and his cricket bat. He was practically penniless when I met him—still is."

Four years ago Imran launched his political party, Tehrik-i-Insaf (the Movement for Justice), which apparently triggered the bombing of his hospital by entrenched interests threatened by his potential popularity as a national leader. "I did say I would take them on," he admits. "I decided this country was going to become unlivable. Pakistan is considered a basket case, a failed state. Politics takes me away from everything I would like to do, but if I want my children to grow up in Pakistan ..." He sighs. "Anyone who can afford to is leaving the country. It's very difficult to hire people; people don't see any future for their kids. Either you go abroad or you join one of these Mafias—or you fight them and try to change the system. I'm considered a very naive politician because of my refusal to compromise. But I am trying to fight the status quo. How can you join the status quo and fight them? I know it's a huge thing to try and make this a livable society, but I think I should try. All my life, my training is the ability to keep picking yourself up and keep fighting. The successful sportsman is the one who never gives up."

He stares off into the distance, scowling. "So I guess I'll try."

But Imran's commitment to politics has required some major adjustments for his fragile young wife. Her French-born father, who had dual citizenship in France and England, maintained homes outside London and in Paris as well as a 17th-century chateau in Burgundy and a family compound in Mexico called Cuixmala, an estate so large that Jemima estimates there are 40 children living in the servants' quarters alone. But Imran's decision to become a Pakistani politician leaves his own family little choice but to live in Pakistan, a challenge even when the water and the electricity are on. (They were off the last time Princess Diana came to visit them, but Jemima, who has often been compared to Diana, says she was a good sport about it.)

In a country where disease is rampant, hygienic standards are abysmal, and even drinking the water can be deadly, Jemima and her children have been chronically ill—a manifestation of frailty that annoys Imran no end. When a friend of Jemima's visited Pakistan and landed in the hospital with a particularly virulent strain of salmonella, Imran said contemptuously, "He's weak!" Imran has no sympathy for complaints about the physical difficulties of life in his native land. "These are things that make you stronger," he insists. "Struggle is good for you. If people avoid struggle, they decay. Life has been very easy for Jemima." He grins. "Maybe I'm a godsend to make her struggle."

Tied down with her babies—three-yearold Sulaiman and one-year-old Kasim— Jemima waits endlessly at home for her elusive husband to return from his rounds of political meetings, hospital-related activities, and of course the obligatory daily workout at his gym. (Imran rhapsodizes about how wonderful it is to have children, but he appears to do virtually none of the actual child care himself.) Much of the time Jemima doesn't know where her husband is; when he doesn't show up, she is often reduced to calling around to the gym or the hospital to try to locate him. "When I'm not here, I never ever get him on the phone before two o'clock in the morning," she says disconsolately.

Curled up on her living-room sofa, Jemima looks pale and ethereal. She is nibbling Cadbury's chocolate brought from England and sipping fresh pomegranate juice squeezed by a servant; after countless bouts of gastrointestinal illness, she has developed such an aversion to curries and other local fare that she appears to subsist largely on chocolate and pomegranate juice. The intensely romantic whirlwind of her early days with Imran seems like another lifetime.

"So much has happened since then, it feels like such a long time ago," she says. "He talked about marriage by our third meeting, maybe even the second. He wasn't interested in having an affair with someone at that stage in his life. He wanted to get married."

They were introduced by Jemima's sister India Jane. "It was quite old-fashioned," Jemima says. "My sister almost made it like a traditional arranged marriage. Imran had said he wanted to have an arranged marriage to a Pakistani girl, because that's what everyone in his family does."

Instead, he set British society agog by sweeping Jemima off her feet. Her mother was sympathetic, but her father was appalled. "Jimmy obviously blew a gasket," confirms Lady Annabel when I visit her later in London. "But he developed the same love for Imran that I did." Family members insist that Goldsmith and Imran had great respect for each other, but what hit the rumor mill was Goldsmith's alleged comment that Imran would make "a wonderful first husband" for Jemima.

India Jane Birley saw deeper. "Imran offered her some sort of moral certainty. That was the one thing Jemima hadn't grown up with," she says. "Besides, what Jimmy inculcated in us was that English men are so incredibly dreary—the most drippy, ghastly people, and the aristocracy are the most decadent and useless in the world. I think Jimmy took an enormous pride in being an outsider."

In choosing Imran, Jemima picked the ultimate outsider, trumping even her renegade father. When the glamorous couple wed, she was 21 and Imran was 42. First they married in a secret Muslim ceremony in Paris. "The only person who knew was my mother," says Jemima. That was followed by the big society wedding staged by her parents and then by a traditional Pakistani ceremony in Lahore. The Khans were just as shocked as the Goldsmiths; when the bride was introduced to Imran's aunt, a relative told Jemima, "She's still recovering from the shock." Imran's aunt glared at them. "Who says I'm recovered?" she said.

Jemima, who has learned Urdu well enough to converse fluently, puts on a brave face about the accommodations she has made since her move. "I was always quite adaptable," she says. "The health problems are the most difficult for me, the fact that I'm quite often sick and the children are sick. But as far as adapting to the culture is concerned, I never had problems with that." She pauses, and then adds, "It may be that my upbringing was so unconventional it prepared me."

'Unconventional" doesn't begin to cover it. Jemima's father was a half-Jewish, half-Roman Catholic financier who began his own infamous romantic career at 20 by running off with an 18-year-old Bolivian tin heiress, much to the horror of her family. Isabel Patino, the granddaughter of a man known as the Bolivian Tin King, died tragically only a year later, suffering a cerebral hemorrhage shortly before giving birth to a daughter, also named Isabel. Her family sued to obtain custody of the baby, and at one point the infant's maternal grandmother, the Duchess of Durcal, kidnapped her. But Goldsmith finally prevailed after a bitter court fight. Although he wept with joy when he won, Isabel has accused him of being "a terrible father, but a fascinating man."

In his grief over the loss of his young bride, Goldsmith turned for solace to his French secretary, Ginette Lery, who eventually became his second wife, bearing him two more children. But then he fell in love with the luscious Lady Annabel, the daughter of the Marquess of Londonderry. She was married to nightclub entrepreneur Mark Birley, who had named his exclusive Berkeley Square club, Annabel's, after her. Although they had three children, Lady Annabel embarked on a scandalous affair with Goldsmith that endured for 10 years before she gave birth to Jemima. Annabel and Jimmy had two more children together, finally marrying when Jemima was three.

But no sooner had Goldsmith married Lady Annabel than he commenced an affair with a 26-year-old reporter for Paris Match, a pretty blonde named Laure Boulay de la Meurthe, the niece of the Comte de Paris, the pretender to the French throne. The arrangement was immortalized by Goldsmith's most widely quoted remark: "When a man marries his mistress, he creates a job vacancy." Goldsmith, whose own brother once described him as "a natural tribal polygamist," proceeded to have two children with Laure. He also purchased Point de Vue—a weekly magazine "so snobbish that its subjects' coats of arms are reproduced at the head of any article about them," as one London newspaper put it—and installed Laure as publication director.

Jemima remains discreet about her mother's reaction, acknowledging only that "there was a lot of hurt." Lady Annabel's heartaches also included the death of her eldest son, Rupert Birley, who drowned off the coast of Africa, and the disfigurement of her second son, Robin, who was attacked at his godfather's wildlife preserve by a tiger, which mauled his face.

Through it all, Goldsmith continued to dominate the lives of all of his wives and mistresses, along with their eight children. "Jimmy was the puppet master," says Lady Annabel. At six-foot-four, he was charming and seductive and seemed a larger-than-life figure to those in his orbit—the ultimate alpha male, according to Francis Pike, India Jane's husband. "He just walked into a room and he was it," says Pike, the chairman of Rothschild Ventures. "He had a very powerful effect."

In Goldsmith's later years he maintained one household with Lady Annabel and their three children at the £7 million Ormeley Lodge, and another in a house once owned by Cole Porter on the Left Bank in Paris, where Laure and her two children were ensconced on one side of the house and Ginette on the other. By this time he had been knighted, and when he died in 1997 at the age of 64, Sir James left an estate valued at a couple of billion dollars and was one of Britain's richest men.

Jemima admits that her father was "quite often absent," but insists she had "a great childhood. My father was very devoted." Many observers believe Jemima was his favorite child. When she turned 20, he flew 100 of her friends to Paris for dinner at Laurent, a restaurant he owned on the Champs-Elysees, and hired a jazz band from New Orleans—a birthday party that reportedly cost £250,000.

Jemima doesn't condemn him for his philandering ways, focusing instead on the positive. "He didn't believe in abandoning a wife when you got divorced," she explains. "With my father, marriage was a piece of paper. Whether he married them or not, he was committed to all those women for life."

But the domestic turmoil he left in his wake inspired a different vision for Jemima. "I always thought I wanted a marriage to work," she says, as if this were a novel idea. "I wanted to make it a lifetime achievement, only to be married once. I went into this marriage wholeheartedly, and my hope is that it will work."

When she met Imran, she adds, "I felt like I'd met a soul mate. He had all the qualities I respected and wanted in a husband. I was just surprised by how early I'd met that person. I would not have expected to get married until my late 20s. But you know that saying about how to make God laugh—tell him your plans." She smiles wanly. "I strongly believe things happen because they're meant to happen. There wasn't even a second I doubted I was going to marry him, or thought it was the wrong thing to do. I didn't have any selfdoubt at all."

But marrying Imran also meant taking on a foreign country and an alien religion. Jemima has tried to embrace Pakistani culture by founding a small clothing business, designing silk-georgette dresses that are hand-embroidered by Pakistani women before being sold at upscale stores such as New York's Henri Bendel. All the proceeds go to Imran's hospital. She is popular enough in Pakistan that a range of sauces has been named after her, including Jemima's Tangy Ketchup.

The religious issues have been exacerbated by the sensationalistic scrutiny of the British and the Pakistani press. Fleet Street has been particularly vicious about the metamorphosis of the gorgeous young heiress into a dutiful Islamic wife: '"Sleepwalking into slavery' was one quote I remember," Jemima says. She prefers to downplay the rigors imposed by Islam. "Wearing the clothes, covering my hair—I have no problem with these things. Some people see them as such a symbol of subservience, but Imran and I have a balanced relationship," she says. "I cover my hair more for cultural reasons, for my own comfort; hair is perceived here as a sexual adornment, and I don't like having men staring at me. I'm careful to be respectful of the culture. Everything is likely to be exploited. Things are used politically, and I'm judged."

Jemima glosses over the fact that Islam permits men to take more than one wife. "I think Imran's got his hands full with one," she says, a touch of acid in her voice. But her husband's friends have long raised their eyebrows at his increasingly rigid adherence to Islam, a marked change from earlier years. The man who once dazzled the smart set in his Armani suits is now more likely to be found in a shalwar kameez and the leather sandals favored by his tribal brethren. Even fellow Pakistanis are taken aback by his impassioned religious absolutism. "I love Imran as a person," said one Lahore socialite. "But I still have this nagging worry that, if he gets into power, he might have me stoned to death for adultery or cut off my head for drinking."

The dictates of Islam are undeniably harsh, especially as interpreted by Muslim hard-liners; asked what would happen if Jemima and Imran divorced, a spokesman for Osama Bin Laden cautioned, "If she renounced Islam, she would become apostate. The penalty is death."

Jemima claims to be unfazed. "I think the older Imran gets the more Pakistani he becomes," she says. "He's moving closer to his roots. It doesn't dismay me."

More pressing are the quotidian difficulties of life in Lahore. Both children sleep with Imran and Jemima. "There isn't room for Sulaiman to have his own room, and he's so attached to me he has to go to sleep holding my hair," Jemima says. "I have bald patches from him tugging on it."

In their living room, the beige wall-towall carpet is stained; the sofas are grimy and sagging; the pillows are ripped. Paint peels off the walls. There is a constant stream of people—servants, visitors, family members—in and out, so Jemima has virtually no privacy. When the telephone is working, which is only intermittently, it rings constantly; everyone ignores it.

"I haven't done anything to this place to make it my home," Jemima admits. "I don't feel it's my place to come in and start changing everything. It's half that, and half that I'm exceptionally lazy about these things. Besides, Imran's plan is to move to Islamabad—that's where all the diplomats and politicians live. It's cleaner air, and it's close to his beloved mountains. But his family's here, and he wants the children to be brought up with all their cousins. Imran's incredibly busy, and it would have been quite difficult and lonely for me not to have had the help and support of his family."

The combination of conflicting goals and inertia has produced a stalemate. In the meantime, the Khan children camp out in a bewildering array of residences. In December of 1998, Jemima bought some tiles at an Islamabad bazaar to ship to her mother for her half-brother Robin Birley's sandwich bars in London. To her amazement, she was charged with smuggling stolen antiquities. In England to await the birth of her second child at the time, Jemima quickly obtained statements from specialists who had been affiliated with the British Museum, Sotheby's, and Oxford University certifying that the tiles in question were modern, made in Iran, and of no archaeological value, contrary to the assertions of the Pakistani government. But the charges stood, and Jemima—fearful of imprisonment without bail by a regime intent on intimidating her husbandended up staying in England for nearly a year, mostly with her mother, although she has also bought her own £1 million house in Fulham (generating another furor in the British press, which trumpeted its conclusion that Jemima's marriage was over). She returned to Pakistan only after Sharif was deposed last fall. After a few weeks of shuttling between Lahore and Islamabad, the Khans then traveled to London for Christmas and on to the Goldsmith retreat in Mexico, where Sulaiman went crocodile hunting with Imran every day on a boat in the lagoon.

"Sulaiman said to me the other day, 'Where's our home?'" Jemima says. "I really didn't know what to say. For him, home is where I am. For me, I suppose home really is my mother's house." For a moment she looks like the little girl who led such a sheltered, comfortable life back in England, where she was an accomplished equestrienne and her greatest worries involved dressage and show jumping.

But in some ways her current life with Imran is oddly familiar. Near the end of her father's life, he formed a political movement called the Referendum Party to advocate a popular vote on whether England should join the European Union, a move that the ferociously right-wing Sir James opposed. His family supported him wholeheartedly, and these days Jemima seems equally respectful of her husband's determination to assume a public role in Pakistan.

"I know he would rather spend time doing the things he enjoys—traveling into the mountains, shooting partridge, being with his family—but he's very patriotic," she says. "He loves this country, and feels he has to do something to help it. He feels it's his duty, and I admire that."

But Imran's quest was difficult even before Sita White entered the fray. He already had a host of political enemies. Now he has to contend with a more personal—and potentially more destructivefoe.

In sunny Beverly Hills, a six-foot-tall blonde is living in Andy Williams's old house just off Sunset Boulevard with her dark-haired, dark-eyed daughter, who turns eight in June. An English heiress like Jemima, Sita White is the daughter of the late Lord White of Hull, a British tycoon. Sita met Imran Khan in London in the early 1980s and plunged into an affair. "I was rebelling against my father," she says ruefully. "He was totally against my going out with Imran; he said, 'You're just another girl in line.' Imran never told me he would be loyal; he always said there would be other women."

Despite Imran's insistence that he would only marry another Pakistani, they saw each other on and off for years. Finally, in 1991, Sita asked Imran to make her pregnant. "I wanted a child from him no matter what the consequences were," she says. "I understood that Imran would never be with me, but I thought it would be O.K. as long as we kept in contact."

After she got pregnant, Sita says, Imran was very concerned about what gender their child would be. "When I told him it was a girl, he said, 'Oh, no—she's not going to be able to play cricket! You should get rid of it!'" But Sita refused to have an abortion, and Imran stayed in touch throughout her pregnancy. "I called him from the hospital," Sita says. "He heard Tyrian cry on the phone as she was being born. He said, 'Who does she look like?' I said, 'She's a replica of you.'"

Sita, who is now 39, wasn't surprised when Imran married Jemima. "He couldn't be with a Pakistani woman—he didn't like them at all," she says. "He wanted a white woman, a blonde woman. Most of his girlfriends are blonde. Jemima stands out like a sore thumb in Pakistan; he wanted that."

But Sita kept quiet about their child until Imran was asked about Tyrian at a press conference—whereupon he made the fatal mistake of publicly denying not only paternity but even his relationship with Sita. "I have never been involved in any affair of any sort with this lady," he said with Clintonesque grandiosity.

"That was the day I said, 'This is it,'" says Sita, who is still enraged. She filed paternity suits in Los Angeles and London, subsequently withdrawing the one in England only after Imran begged her, fearful that he would be slapped with an embarrassing subpoena upon leaving the memorial service for Sir James. Despite Imran's refusal to provide a blood sample for a DNA test, a California judge declared him Tyrian's father by default.

'When I told Imran he should have admitted it, he said, 'You don't understand—you get stoned to death here for having a child out of wedlock,'" Sita explains. "So he lied. He thought I was just going to walk away from it and say, Oh, who cares. But it was the principle of the thing—the fact that he denied it. It really hit me in the heart. I thought, My God, this man is nothing of who he said he was! Whether I've marred his career, I don't really care. It's about a child. I've never asked him to pay any child support. When I got pregnant I said, 'All I want from you is just to be there; call when you can.' That's all I asked, and he still couldn't do it. Now he's got to take the consequences."

Little Tyrian Jade bears an uncanny likeness to her father, but he has tried his best to pretend she doesn't exist. He had never even met her until October of 1998, when Sita ambushed him at a hotel in Los Angeles where he was giving a speech and forced a meeting upon him. Tyrian was so excited she wore a white flowered dress and carried two handbags. But since then there has been only silence. Recently, Tyrian made a drawing festooned with hearts that shows her holding hands with her father. "Dear Daddy I love you!" she wrote. "I am in L.A. I want you to come to my birthday, remember 6/15/2000 my birthday." Tyrian asked her mother to have the drawing published in a newspaper so her father might see it and get in touch with her.

Imran Khan is a man who believes in destiny, and his wife says he has no fears. "Because of his faith in God, he's not afraid of dying," Jemima says. "He's really not afraid of anything." ("Except your driving," Imran interjects.) Little Sulaiman claims that his father is "strong as an elephant, brave as a lion, clever as a wolf." ("That's what Imran has told him," Jemima explains.) But Imran would do well to fear Sita White.

"I don't believe he'll be able to run for prime minister—not while I'm around," she says. "If he aggravates me enough, I will sink his ship. It would take me two seconds to put that paternity suit back on him, and the one in London is the one he fears most. All I'm asking is that he communicate with his daughter; he can do that privately, and I will never say anything again. But he doesn't call her— nothing."

In public, Imran refuses to comment on the situation, which he sees as a private matter that has been unjustly exploited by his political enemies. Jemima tries hard to remain philosophical. "Imran has never said he was any kind of angel in his past life," she points out.

But his fellow Pakistanis are having a difficult time reconciling the old Imran of the playboy glamour and the illegitimate child with the present-day Islamic zealot who makes increasingly strident statements about moral values—notably his attacks on what he calls Pakistan's pampered "brown sahibs" and his declaration that corrupt politicians should be hanged.

"Before he married Jemima, he made a series of pronouncements in which he slammed the Westernized elites of Pakistan and said we were aping the West," explains Jugnu Mohsin, the publisher of The Friday Times, an independent weekly in Lahore. "He is very dismissive of the 'decadent' ruling elite. He advocated a return to tribal family values—and in the next minute he went and married Jemima. Because of his wife, he is seen to have one foot in London and one foot in Pakistan."

Mohsin sighs. "He's so valuable to us because of his integrity; all the other politicians are rogues and brigands and thieves," she says. "I believe he's better than the rest of them. I think he's genuine; I think he's clean as a whistle. I like him— but I don't necessarily think he's statesman material, because I think he's confused. He has too many contradictions in his worldview. You can't have that and appear to be a messiah. He's chosen a modem Western woman for a wife, but he's essentially an agent of the past, because of his policies—and if he's an agent of the past, he's not a man of the future. You either have to integrate Pakistan into the world and understand what globalization means and make the best of it, or go the isolationist route—but you can't defy the world on the one hand and beg for the loans and handouts on the other hand. Imran has to resolve those contradictions. And perhaps he will—but in the absence of a coherence which he seems to lack, people will vote for those who will get their children jobs and get them electricity. In the absence of inspiration, they will opt for survival."

At fashionable parties of late, acquaintances whisper that Jemima has told intimates that if she had known five years ago what she knows now, she would never have chosen this life. So far, however, she is standing by Imran and his political goals. "It's so rare to find someone who has that kind of passion in his life—such a strong belief that it completely fires them," Jemima says. "There are times when I wish, 'Why don't you just give up politics and be with your family?' But his selflessness is quite humbling. It's tough having a husband in politics, but I'm not going to leave him for that reason. I either accept it or I bail out, and I'm not going to bail out. And he's not going to bail out of politics either."

Imran certainly doesn't sound like a man who's prepared to give up. "I have a certain vision," he says. "You can compromise for the sake of the vision."

He glares at me, his hawk-nosed face devoid of any hint of a smile. "But you cannot compromise on the vision."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now