Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

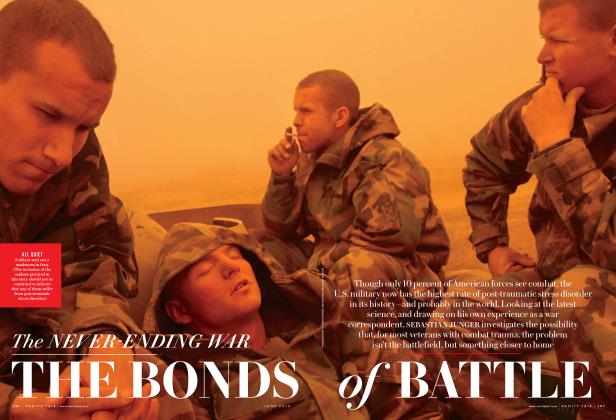

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn an Instant, War

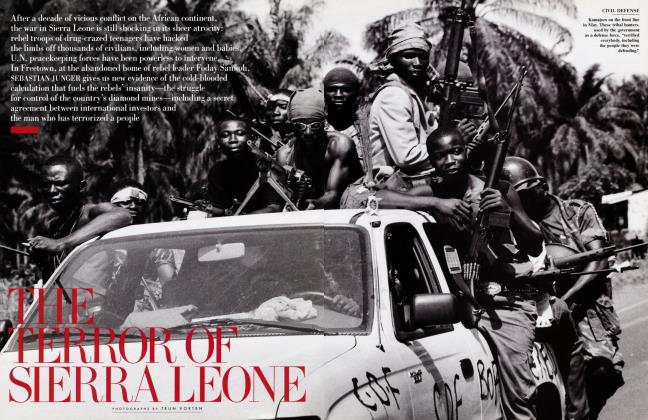

Late last June, the international press corps gathered at the Skopje Holiday Inn, watching what looked like a remarkably nonlethal Balkan conflict. Macedonia’s military couldn’t shoot straight, and the Albanian rebels were available by cell phone. Then one afternoon, SEBASTIAN JUNGER reports, things got ugly, revealing how deep the fault lines are in a perilously divided country

My hotel pulled open the window and leaned out. I heard the sound of 5,000 people screaming for war.

room faced west, which was the wrong direction; if I wanted to see anything at all, I had to walk out into the hallway. From there, while waiting for the elevator, I could lean out the eastward-facing windows and look across an ugly jumble of concrete buildings toward the Crna Gora— the Black Mountains—which were now

filled with ethnic Albanian rebels. The mountains were low and lifeless in the summer heat, one long, brush-choked ridge that extended to the Kosovo border, 15 miles away. A few weeks earlier the National Liberation Army, as the rebels called themselves, had picked their way along the flanks of those mountains to a suburb of Skopje called Aracinovo, where they quietly began digging trenches and building bunkers. When they were done they put up a roadblock at one end of town and made it clear to the authorities that they could no longer enter.

What one could see—out of the eastwardfacing windows of the Skopje Holiday Inn late last June—was the Macedonian government’s response. Tank rounds flashed against the hillsides six miles from the center of the capital, and attack helicopters pounded overhead, spewing heat chaff into the watery summer sky while they dumped their missiles. Government tanks left huge, strange tracks in the wheat fields along the national highway as they maneuvered for better shots. There was a rest area and gas station that offered a good view of the events down the road, and it was filled with journalists and TV crews and families with children. In 1861, high-society Washingtonians picnicked on the hilltops during the First Battle of Bull Run to watch the Union and Confederate armies try to annihilate each other, and this wasn’t much different. Both made for good theater, and watching didn’t seem wrong or dangerous, because no one had really begun dying yet.

There were about 200 rebels in Aracinovo, under a commander named Hoxha (pronounced “Hoja”). They were part of a force of several thousand who had occupied the mountainous strip along the border with Kosovo earlier in the year. The rebels were demanding, very broadly, equal rights for Macedonian Albanians, who represent 30 percent of the population. More specifically, they were demanding that Albanian be acknowledged as a second official language, that more Albanians be included in the national police force, and that changes be made to the Macedonian constitution that would reconfigure the country as a federation composed of separate Slavic and Albanian entities. Few reasonable people, it seems, would take up arms over such subtleties, and fewer still would take up arms to prevent others from attaining them, but this was not reasonable. This was the Balkans.

Hoxha and his men waited in their bunkers while the politicians argued. President Boris Trajkovski, a moderate Slav who had come to power in 1999 on the Albanian swing vote, was caught between hard-liners in the military, who hardly conceded citizenship to the Albanians, and Albanian extremists, who were trying to forge a Greater Albania in the Balkans. The main sticking point was the constitution: if it was changed so that the Republic of Macedonia became a federation, then the Albanians would have veto power in the parliament, which would give them the ability to tear the country apart. Without the veto, however, they would always be subject to the whims and insults of the Slavic majority.

Negotiations lurched along for 11 days, until the strain of keeping the peace became too much, and on June 22 the Macedonian military launched a fullscale attack on Aracinovo. Commander Hoxha—who has a cell phone—called the authorities from his bunker and threatened to drop mortar shells into Skopje if they didn’t call it off, but the army’s response was to bomb Aracinovo even more fiercely. A fault line had developed in the Macedonian government between those who were willing to negotiate with

the rebels and those who wanted to kill them. The latter group—Socialist-era generals and other rabid nationalists—had started to take matters into their own hands.

A s it happened, the Macedonian government had / taken delivery earlier in / the week of four Mi-24 r-attack helicopters and / four Su-25 fighters from —1— —A_Ukraine. It was rumored

that a local pilot had flown one of the new helicopters into a utility pole; in any case the government hired half a dozen Ukrainian pilots. Early in the morning of June 22, they climbed into their aircraft and started making runs at the rebel positions. Tanks hammered Aracinovo’s cheap cinder-block houses from below, and artillery in the Crna Gora range dropped shells from above. They allegedly went through a million dollars’ worth of ammunition a day; they bombed until Aracinovo was nothing but rubble, and then they bombed some more. They bombed until it seemed there couldn’t have been one living thing left alive in the town, and then they sent in their Special Forces.

When I flew into Skopje, the attack helicopters were back on the tarmac—my plane taxied right past them—but the battle was still going on; I could hear the bump and thud of artillery in the distance. Macedonian officials weren’t talking much about what was happening to the Special Forces, but it couldn’t have been good. According to a NATO intelligence officer I spoke with, the rebels just waited out the bombardments in their bunkers and then popped up whenever there was a lull. It’s hard to shell and attack at the same time without killing your own men; invariably a lull meant the army was about to launch a ground attack. The rebels simply picked off the soldiers as they came up | the street. 5

By five o’clock that afternoon, the lob2 by of the Holiday CONTINUED ON PAGE 362 with journalists who had just come back from a long, hot day at the highway rest area. They clustered around a television above the bar, smoking furiously and watching their own footage of the attack helicopters rocketing Aracinovo. At one point a tank fired at two distant figures—rebels— who were sprinting for cover at a roadblock; they were enveloped in a cloud of smoke and then re-emerged a moment later, unscathed. Off in one corner, a BBC reporter in a pink shirt and new Timberland boots was pacing back and forth with a cell phone, telling someone he’d just interviewed, “You’re going to be on TV in 10 minutes. You know, that part where you say, ‘People don’t make war, politicians do.’”

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 324 Inn WaS filled

No one could get inside Aracinovo, but an Agence France-Presse reporter spoke with Hoxha on his cell phone, and Hoxha said that his men had easily repulsed the army’s attack. “They got a little way in but ran into a trap we had set,” he said. “We burned four or five of them, and they ran away.”

The fighting, such as it was, had become hard to take seriously. Most of the journalists at the bar had covered wars where people died by the tens of thousands and being anywhere near the Fighting was extremely dangerous. In the early 1990s in Sarajevo, you couldn’t walk down the street for fear of getting shot at by snipers. Now, in Tetovo— a predominantly Albanian city in northwestern Macedonia—you could sit at a cafe in the town square and watch the army shell rebel positions a few hundred yards away on a hillside. The rebels shot only at policemen and soldiers—no one I talked to could think of a single civilian death on the

Slavic side—while the Macedonian Army gunners were so wildly inaccurate that, when they shelled a village, all they usually managed to kill was the local livestock. Occasionally, Albanian civilians died in a cross fire, but that was blessedly rare. And the fighters themselves almost never died. At one point I asked my translator, Erol, how many soldiers had been killed in four months of war.

“I don’t know exactly,” he said. “But let me see ...”

To my amazement Erol labored over the numbers month by month—three here, four there—until he’d added it all up. “I think,” he announced proudly, “that maybe it is about 30 or 40.”

T n a war where almost no one was dying A and you could call rebels up on their cell phones to ask how the battle was going, it was tempting to dismiss the whole thing as some kind of son et lumiere extravaganza projected onto a hillside outside town. What journalists were missing—what I was missing, at any rate—was the fact that underneath it all the society’s temperature was fast approaching the boiling point. The Albanians had been grumbling about their rights ever since Macedonia split off from the Yugoslav Republic in 1991, but it was all pretty much cafe chatter until last February, when a few dozen rebels took over a village called Tanusevci, near the Kosovo border. The government quickly denounced them as terrorists and dispatched the army and police to deal with the problem, but to its immense embarrassment they made no headway. The rebels were battle-hardened by three years of war in Kosovo, while the national police and army were mostly young recruits who had zero interest in dying to retake some Albanian village in the mountains.

Valley by valley, ridge by ridge, the rebels took over the rugged border area between Kosovo and Macedonia. Occasionally they ambushed police convoys or attacked army posts, but for the most part they just walked into Albanian villages and set up checkpoints. Their weapons came across the border from Kosovo, mostly on horseback, and their money came from a 3 percent “war tax” levied on Albanians working in Europe and America. In addition, a network of Albanian strongmen who had run weapons and contraband into Kosovo during the war against the Serbs were now engaged in arms trafficking, prostitution, and gunrunning in Macedonia. The rebel army and the Albanian Mafia—while not quite the same thing—were closely linked. The chaos of war helped the Mafia thrive, and a thriving Mafia helped pay for the war.

Some Slavic nationalists seized upon the organized crime as an excuse to dismiss the perfectly legitimate demands of Albanian political leaders. Their solution—bomb the rebels into nonexistence and threaten everyone else into good behavior—would have worked in, say, Serbia or Russia, but this was not Serbia or Russia. This was Macedonia, a country where the police couldn’t shoot straight and air-force pilots weren’t allowed to fly their own planes. Every time the Macedonians tried to dislodge even a handful of rebels from a town, the rebels either melted back into the mountains or fought the security forces to a standstill. When they resorted to artillery to do their work for them, civilians died and the world grew more sympathetic to the rebels’ cause. In early May, a high-ranking NATO official referred to the rebels as “murderous thugs” who could not be negotiated with. By June the rebels had graduated to “armed elements,” and were in direct contact with NATO officials. A backlash against the Albanians was inevitable. Several months into the war, the ultra-nationalist minister for internal affairs, Ljube Boskovski, 40, distributed 15,000 Kalashnikovs to hastily deputized civilians. They became the core of a highly nationalistic force of reservists who were under his command. He followed that with his opinion that all Albanians who had become citizens since 1994—Kosovo refugees, in other words—should be expelled from the country.

It didn’t take long for the young hoodlums in town to get the hint. On Saturday, June 23, an Albanian newspaper in Skopje reprinted a note that had started appearing on the windows of Albanian-owned shops. It was from a Slavic group called Macedonia Paramilitary 2000, and it began, “All Albanians who own stores have three days to move out.... Otherwise, the stores will be burnt. If any Albanians try to defend their stores, they will be killed.” The note went on to threaten to kill 100 Albanians for every policeman or soldier who died in the fighting. As for Albanians who had become citizens after 1994, they had until June 25 to leave the country or they would be ethnically cleansed in “Operation Longest Night.”

O till, things seemed so normal—cafes in Otown full of pretty girls, old men still fishing the shallows of the Vardar River— that no one realized it was a country teetering on the edge.

The same day that Macedonia Paramilitary 2000’s decree appeared in the press, the European Union’s foreign-policy chief, Javier Solana, 59, flew into the Skopje airport to try to salvage the peace process. His exit from the plane was delayed several minutes by a Ukrainian pilot who roared 100 feet over his head in one of the new Su-25s. That prompted Solana to remark that the Macedonian military “doesn’t need to send messages like that. I have a mobile telephone.”

Within a day, Solana had negotiated a cease-fire, but it quickly broke down when the rebels changed their mind and refused to pull out of Aracinovo. Apparently they had waved white flags to indicate they were prepared to leave their positions, but the local press had seized upon this as proof of defeat. Another round of fighting, and another round of threats and pleas by Solana, resulted in another deal: The rebels would leave town as long as they could keep their guns, and they would be replaced by international monitors who would make sure that no one resumed fighting. The Macedonian government, for its part, would call off all attacks and return to the negotiating table in good faith.

Immediately there was another snag. The rebels were to be moved by bus, but the drivers of the local bus company—who were Slavs—refused to venture into Aracinovo, even with a NATO escort. An Albanian-run bus company was found in Tetovo, but it didn’t own enough buses to move everyone. Only at Camp Able Sentry, a logistical-support base for American troops in Kosovo, were there willing drivers and enough buses to move the nearly 400 rebels and civilians out of Aracinovo. With its flair for getting things done quickly, the U.S. Army dispatched a 42-vehicle convoy. The town stank of dead cattle, and most of the houses had been destroyed, but the defensive works—the trenches and bunkers—were still intact. The Macedonian assault, in other words, hadn’t come close to working.

“The rebels were extremely well disciplined; some wore bandannas around their heads, but they were not Che Guevaras at all,” a NATO official who went into Aracinovo told me. “I would say it would have taken a force of at least 2,000 men to get them out of that village, and there would have been 200 casualties. Look at Chechnya—70,000 Russian soldiers couldn’t defeat 3,000 rebels.”

TVT aturally this was not the story told by 1 I the Macedonian military, and it was not the story that the Macedonian public wanted to hear. A young police officer who had arrived in Aracinovo on the second day of the assault told me that the rebels—he called them terrorists—had suffered 1,000 killed and 500 wounded. By the time the armed forces called off the attack, he said, the rebels had been penned up in 10 houses on the outskirts of town and were on the verge of being wiped out. NATO had essentially gone in and saved them. Without NATO interference, he said, the Macedonian military would have finished the job within days.

In fact, the military had been completely humiliated. In an effort to escape the understandable wrath of the public, the more anti-Albanian elements of the government and military were explaining the evacuation as a massive NATO betrayal. On the afternoon of Monday, June 25, a crowd of several thousand protesters gathered in front of the parliament building to protest the deal President Trajkovski had made with the rebels. As the sun set there were fewer and fewer families in front of the parliament, and more and more belligerent young men in fashionably militaristic haircuts. The handful of police who were there to protect the building stood aside as the crowd started to destroy government cars parked in the area. Michael Pohl, a BBC cameraman, was caught by the crowd and badly beaten. Even most Macedonian journalists—Slavs—didn’t dare take photographs for fear of being attacked. The crowd was demanding that NATO leave Macedonia. They were demanding that Trajkovski resign. They were demanding that the Albanians be gassed to death.

T missed all of this. I had driven to Tetovo _L because heavy fighting had broken out there, and I got back to Skopje in the middle of the evening, tired and hungry. I turned on the television to check the 10-o’clock news before going to bed, and there was footage of a crowd rioting in front of their own parliament building. The building was oddly familiar, and as I stared at the screen, I realized that this was Skopje. It was happening two blocks away. I pulled open the window and leaned out, and heard something I never thought I’d hear in my life. I heard the sound of 5,000 people screaming for war.

Things happened quickly after that. Down on the street, double rows of armed men in camouflage—army reservists—were marching toward the parliament singing the national anthem. Someone unleashed a burst of gunfire into the air, and the crowd roared. More people started shooting, and the crowd grew wilder. The head of the national police, Risto Galevski, grabbed a bullhorn and exhorted the crowd, “If you want to fight, you can come down to the police station. We will give you uniforms and guns so you can fight the terrorists.”

The reservists joined the crowd and together they overran the police lines in front of the parliament. They swarmed inside and started throwing furniture out of the windows and searching room to room for the president. Five minutes earlier, supposedly, Trajkovski’s bodyguards had rushed him out the back door and into an armored car.

The machine-gun fire was very heavy now, and—crouching on my balcony with the lights off—I could hear the crowd starting to smash storefront windows, coming closer and closer to the Holiday Inn. A rumor had swept the hotel earlier that after they were done with the parliament they would come for the foreign press, and almost every international journalist was locked in his room, waiting to see what would happen. I went out to check on the other journalists: the New York Times correspondent had been in his bathroom, writing an article by headlamp; the BBC cameraman had just returned from the hospital and was sitting in the lobby, his face strapped with bandages.

I packed a small bag and hid my press pass and waited. The crowd reached the hotel and started destroying cars that had “TV” or “Press” taped to their windshields.

After a while I couldn’t take it anymore, and I called my editor in New York, who called the State Department. Twenty minutes later my phone rang, and an official from the American Embassy was on the line. I asked him if we should try to get to the embassy.

“No,” he said, “you’d never make it.”

“What do we do if the crowd comes into the hotel?”

“Call me and tell me.”

“The hotel is filled with foreign journalists,” I said. “Do you have any kind of contingency plan for getting us out of here?”

“No,” he said, “not really.”

The crowd was making its way toward the American Embassy and toward the Albanian part of town as well. The police managed to head them off. Shooting started on the other side of town, by the army barracks, and was answered by reservists in front of the parliament. It was two in the morning by now, I’d been up 20 hours. I left the window open so I could hear what was going on down on the street, and then I tried to get some sleep. From time to time a burst of gunfire would jolt me awake, but the energy of the protest had clearly dissipated. People were tired, they were going home. The disturbances grew fewer and fewer until it was completely quiet, and the city finally put itself to sleep.

IVT hat I’d seen had all the makings of a W coup. Miraculously, no one was killed, and Trajkovski was still in power the next day, but the country had come close to complete dissolution. A night of running amok in the Albanian quarter, a shoot-out between reservists and police loyal to the president—almost anything could have precipitated a horrific bloodletting. At a press conference the next day, NATO’s political director, Daniel Speckhard, was peppered with

questions from irate Macedonian journalists, who demanded to know why NATO had helped the rebels “escape” from Aracinovo. Speckhard displayed an almost superhuman patience.

“Our efforts came at the request of your government to help remove armed elements from Aracinovo,” he said. “The idea that a military success was near ... is totally false. You are doing a disservice to your readers if you perpetuate that myth.”

A local journalist, clearly puzzled by the gap between what Speckhard was saying and what he’d been hearing from his government, finally stood up. “This will be a short question, and I want a short answer,” he said. “Did the stopping of the offensive mean we could not take the village militarily?”

Speckhard paused. The question was almost poignant. One journalist—if not a roomful of them—was about to learn that his government had been duping him for months.

“There is no indication that the Macedonian security forces had been able to proceed very far, if at all, into Aracinovo,” Speckhard said slowly. “To answer your question: Yes, capturing Aracinovo house by house would have cost many, many lives.”

Tleft Macedonia a few days later. Fighting X flared and then died and then flared again. Rebels came down out of the hills around Tetovo and attacked government forces in the streets of the city. The army responded by shelling, which killed seven civilians. The rebels ambushed an army convoy, killing 10 soldiers, and then mined a road outside Skopje, which killed eight more. Back and forth it went, all through July and early August, until on August 13, President Trajkovski announced that a tentative agreement

had been reached. It was called a “framework document,” and it offered almost everything that the rebels were asking for: Albanian would become an official language, Albanians would make up one-sixth of the national police force, and certain sensitive majority decisions in parliament would have to include a majority of the Albanian vote. Just hours after the document was signed, however, artillery was rumbling in the Crna Gora. Clearly, the peace—the entire society— could break down over almost anything, and there are extremists on both sides who would probably prefer that to happen. A few weeks after the crisis in Aracinovo, it came out in the press that the American soldiers who escorted the rebels out of town had come perilously close to getting into a firefight themselves. Outside a small town called Umin Dol, they had run into a mob of angry Macedonians mixed with police and armed reservists. The crowd blocked the convoy, tempers escalated, and at one point a police officer ran forward and started shooting his pistol in the air.

The man was eventually led away, but it was a precarious moment. The American commanding officer would certainly have defended the convoy if it had been attacked; a shoot-out between American soldiers and Macedonian reservists would have been an unimaginable disaster. Any number of things could have happened—angry reservists could have besieged NATO troops, nationalistic thugs could have started killing Albanians, Hoxha could have come down out of the Crna Gora and infiltrated Skopje. Umin Dol could have become one of those little places in the world—like Mogadishu or Khe Sanh or Sainte-Mere-Eglise—known to almost every person in America, at least for a little while. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now