Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

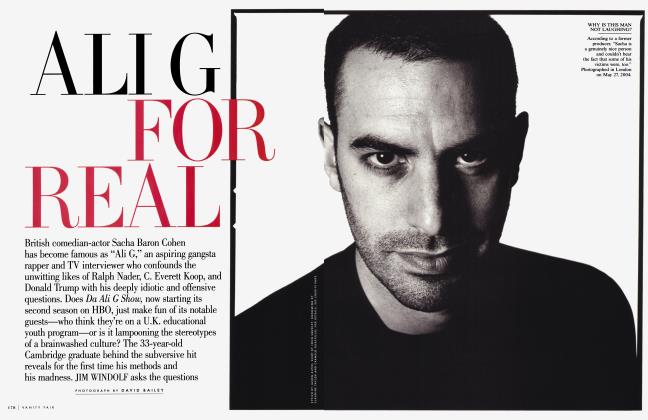

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter becoming C.E.O. of General Electric in 1981, Jack Welch was ranked as one of America’s toughest bosses for the layoffs and “Fix, Sell, or Close" strategy by which he revolutionized the company. Two decades later, he had made G.E. the most valuable corporation on the planet—and himself the most admired C.E.O. of his era. Now, with Welch’s retirement and memoir arriving, DAVID MARGOLICK finds him on Nantucket, to talk about how he wrestled with the recent Honeywell-merger and Hudson River-PCB controversies, why he’ll never again drink inexpensive wine, and what he left out of his book

October 2001 David Margolick Annie LeibovitzAfter becoming C.E.O. of General Electric in 1981, Jack Welch was ranked as one of America’s toughest bosses for the layoffs and “Fix, Sell, or Close" strategy by which he revolutionized the company. Two decades later, he had made G.E. the most valuable corporation on the planet—and himself the most admired C.E.O. of his era. Now, with Welch’s retirement and memoir arriving, DAVID MARGOLICK finds him on Nantucket, to talk about how he wrestled with the recent Honeywell-merger and Hudson River-PCB controversies, why he’ll never again drink inexpensive wine, and what he left out of his book

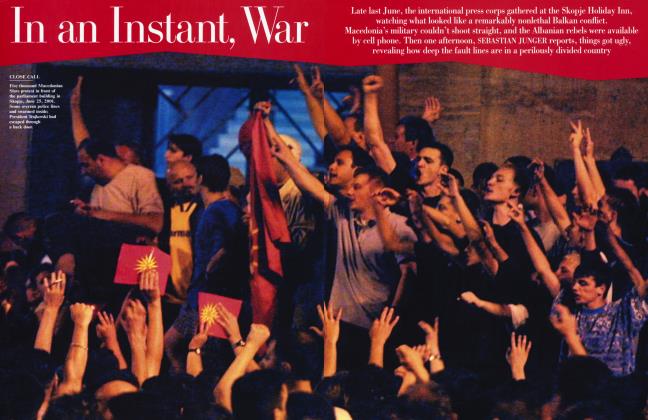

October 2001 David Margolick Annie LeibovitzIt was nearly eight one morning in early August, and Jack Welch, like half of Nantucket, it seemed, was waiting for the Siasconset Market to open. Unlike the children in their sandals and swimsuits, he was not there for the hot blueberry muffins, and it was too early for a fat-free Fudgesicle, one of his few postcoronary-bypass indulgences. Instead, he went directly to the pile of newspapers by the door. He already knew what The New York Times would say: that Christie Whitman of the Environmental Protection Agency was ordering General Electric to clean up the toxic chemicals it had poured into the Hudson River from the mid-1940s to 1977. He’d been called about the decision last night at his country club, and had since read the Times piece on-line. But now, here it was on old-fashioned newsprint, a stark two-column headline draped over the right-hand side of the front page—WHITMAN TO ISSUE ORDER TO DREDGE HUDSON FOR PCB’s—and it disgusted him anew.

He pointed to the subheadline—BIG DEFEAT FOR GE—and snorted. Then he read aloud two quotes attributed to an unnamed “senior official” at the E.P.A. ‘“It’s time to move on, and we’re committed to cleaning up the river,’” Welch huffed. “I love it. That’s thoughtful.” He resumed reading: “‘The agency believes it’s time to move forward, and our own scientists have said we won’t learn everything until we do some of this stuff.’ Imagine,” he said, now resorting to paraphrase. “‘We’ll find out as it goes along. We don’t know where it’s going, but we’ll take a survey.”’

Those pesky PCBs beneath the Hudson have framed Jack Welch’s 20 years atop G.E. “I came in and the PCBs were there; I’m leaving and the PCBs are there,” he has noted matter-of-factly. Sure, he could have just caved in long ago and coughed up the roughly $500 million it will take to remove them, and he could easily do so now; there is no statute of limitations on largesse. That was precisely what everyone—Howell Raines at The New York Times and John Huey at Fortune, to name just two—had been urging him to do. For G.E., the cost is a pittance. But Welch has always gone with his gut, and his gut had told him it’s wrong: bad law, bad policy, bad science. His friend in the White House had obviously capitulated, but he would not budge. With legal appeals, the war will last another 30 years, he predicted, destined to bounce around long enough to land on the desk of his successor’s successor.

Welch didn’t dip deeper into the paper, at least at the store. Had he, he would have found the latest in the other ongoing Jack Welch saga, concerning the move he once predicted would be “the cleanest deal you’ll ever see”: G.E.’s bid to buy the electronics conglomerate Honeywell. The word today was that G.E. would appeal the European Commission’s rejection of the deal—not for another crack at Honeywell, which was hopeless, but to make sure that when G.E. seeks to swallow up yet another company it won’t be hamstrung by the precedent.

For the 65-year-old Welch, the Honeywell and Hudson River fiascoes threaten to snap one of those unbreakable streaks of triumph or endurance that Americans so cherish, like Joe DiMaggio’s or Cal Ripken Jr.’s. In the two decades he has run G.E., he became the Sultan of Superlatives. The business press has christened him “the manager of the century,” “the most admired, studied, and imitated C.E.O. of his time,” “the central figure in the consciousness of the world’s business community.” Welch fixed a company that no one else ever knew was broken, turning a venerable industrial colossus into a manufacturing and financial-services conglomerate. He made G.E. the most valuable corporation on the planet and turned thousands of G.E. stockholders, including anyone who’d bought $17,000 in stock when he took over in 1981, into millionaires.

Welch’s methods became a model throughout the world. Executives everywhere emulated him. G.E. became the farm system for Corporate America, and Welch disciples are now sprinkled throughout the Fortune 500. Sure, he’d upset people, laying off thousands, closing down or selling off huge and beloved pieces of the company. “Neutron Jack,” they’d called him, vaporizing people while leaving buildings intact. But his modus operandi had long since become standard business-school doctrine, and as it did, Welch had gone from hatchet man to seer. For four years running now, G.E. has been named the most admired corporation in America by Fortune magazine. Jurgen Schrempp, the head of DaimlerChrysler, actually likes being called “Neutron Jurgen.” Even Naderites conceded his importance, if negatively. “GE under Welch has indeed been a leader; it has set the tone for the hard-edged, stock price-obsessed, anational, ruthless and cut-throat orientation that is now accepted as the norm,” stated a recent issue of Multinational Monitor, a Nader magazine.

Welch retires this month, and while his list of accomplishments is lengthy, his legacy remains malleable, at least a bit. In the inevitable postmortems and career retrospectives to come, how high up will Honeywell and the PCBs go? It is hard to say. But Welch himself will soon weigh in, and he will be difficult to ignore. His new book, Jack: Straight from the Gut, appears on September 11. Four days after he vanishes from G.E., Jack Welch will appear just about everywhere else.

Four publishers vied for Welch’s book, with bids beginning at $4 million. At one point Rupert Murdoch, whose News Corporation owns HarperCollins, tried to pre-empt the process by calling Welch directly. “Name your number,” he told Welch. Welch nonetheless stuck with the auction and went with Warner Books, for $7.1 million. Had he not stopped the process—“I felt somewhat dirty. . . . I couldn’t stand the embarrassment”—the price might have gone even higher. With the sale of foreign rights, Welch’s agent, Mark Reiter, says the take should eventually exceed $10 million, more than Hillary Clinton got for her memoirs, and almost as much as Bill did. That’s chump change to someone who made nearly $70 million last year and hundreds of millions overall; he’s donating the royalties to charity.

Jack will have the might of two media giants behind it: G.E. (which owns NBC) and AOL Time Warner (which owns Warner Books). The Today show is featuring Welch two days running; various tentacles of AOL Time Warner will offer Jack chat rooms and publish Jack excerpts and put Jack on Larry King Live. Meanwhile, there are the Jack blurbs—from, among others, Michael Eisner, Warren Buffett, and Nobuyuki Idei of Sony, who all laud Welch for his brilliance; Idei all but thanks Welch for sharing it with the rest of us.

Warner has to sell a million copies to break even, and a million and a half to be happy. That won’t be easy, given the staggering array of Welch books—all purporting to bare his secrets for success—already out there, several of which will be rereleased to piggyback on Jack. Welch himself calls the Welch books “a cottage industry.” Then there is the question of whether Welch has already peaked. A Republican president he supports could not help him with Honeywell, then betrayed him on PCBs. The New Republic, noting that G.E. had been doing well before Welch and had been outperformed by other companies (with less flamboyant C.E.O.’s) during his tenure, recently labeled Welch “America’s Most Overrated CEO” (and the editor of Business Week is said to have ordered all his top editors to read the piece). Then the Times called the Honeywell deal “a case study in miscalculations,” in that G.E. failed to anticipate the anti-trust concerns of the Europeans. When Jack falls into its hands, the formerly sycophantic press could pounce.

“There ain’t that much agony! It’s wild, it’s fun, it’s great wine, you see great people. This job is all the nuts. This job is not agony. You get to play great golf courses.”

To Welch, neither setback is a personal rebuke; in each, he suggests, he simply got caught up in political forces larger even than himself. His publisher, Laurence Kirshbaum, is equally unconcerned. “I don’t want to say, ‘Fuck you,’ but the so-called critics will not matter on this book,” he predicts. “There are millions of executives out there who, like myself, believe that Jack Welch is the most important business mind of our time, and they will respond accordingly. In the end it’s not what you or I or Fortune or Time or any magazine thinks, but what middle managers in Wichita, Kansas, will think.... And I’m willing to abide by their verdict.”

Then again, the ebullient Kirshbaum— who won over Welch by reading G.E.’s annual report before they met, then grilling him on why “the appliance division has been flat,” precisely the kind of discussion that Welch most relishes—has seriously drunk the Kool-Aid, or the Welch’s: he says that Welch’s account of visiting the two also-rans for his job, and telling them that they had been passed over, drove him to tears. “I literally broke down,” Kirshbaum says. “My wife came into the room and thought something was wrong.... I haven’t cried that hard since my father died.”

While it now has its Gospel According to Saint Jack, the church of Welch already had some sacred texts: Welch’s notes, diagrams, and graphs, many reproduced in the new book. (Cocktail napkins, not parchment, are the usual medium.) It also has its high priests—“A” players, “Type 1 ” managers—who have imbibed Welch’s teachings. It has its holy land: Crotonville, the G.E. study center 40 miles north of New York City where Welch regularly lectures. It has its apostles: those editors of Fortune, Forbes, and Business Week who have regularly placed Welch on their covers and canonized him in their pages. “If leadership is an art, then surely Welch has proved himself a master painter,” John A. Byrne of Business Week wrote in one representative story, from 1998. (Welch subsequently hired Byrne to co-write his book, for which he received an estimated $800,000 fee.)

The church of Welch has at least seven deadly sins: pomposity, closed-mindedness, bureaucratic thinking, sentimentality, loyalty, hubris, and indifference. Welch has faced his doubting Thomases—orthodox G.E. types who considered him a heretic and tried to hold him back—and experienced his fair share of revelations: for instance, he first hatched the idea of “boundarylessness”—his vision of a creatively permeable organization through which ideas flow unimpeded by walls or hierarchies or borders—on a beach in Barbados. And while there is no Kyrie or Agnus Dei, there is the Welch Credo: the “G.E. Values” printed on laminated cards that all employees, Welch among them, carry around in their wallets.

For all his modesty, Welch can sound almost divine. “Every day, I tried to get into the skin of every person in the place,” he writes of G.E. “I wanted them to feel my presence.” (That may now be more difficult for him, but to G.E. employees, at least God isn’t dead; he’s merely going into retirement.) He certainly sounds righteous. “I stuck to some pretty basic ideas that worked for me, integrity being the biggest one,” he writes. “There was only one way—the straight way.”

Welch regularly, almost eagerly admits he’s fallible, and ticks off his mistakes: managing a factory that blew up, buying the scandal-plagued brokerage house of Kidder, Peabody, backing the XFL. But never, ever, he claims, has he acted improperly or unethically or inhumanely. Of the tens of thousands he fired, for instance, only one appears to gnaw at him—the man whose young son took a swing at Welch’s boy on the school bus the next day—and there only because young Welch was so traumatized by the event. That anyone could consider him unscrupulous absolutely dumbfounds him. “Do you for a minute believe that if we thought PCBs were harming anyone I or my associates would be taking these positions?” he writes. “There’s just no way!”

From a distance, maybe from the banks of the Hudson or alongside a padlocked plant, Welch is easy to demonize. But down-to-earth, unstuffy, a famously regular guy, he is hard to dislike up close. “You sort of hate to like the guy,” says Helen Quirini, an 81-year-old G.E. retiree and union activist who has clashed with him over the company’s measly pensions. “I think he’s a classy man, to be honest with you,” adds Pat Daly, a Dominican nun active with the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, whom Welch once lectured—“You owe it to God to be on the side of truth here”—about PCBs. The two runners-up in the race to succeed him, James McNerney and Robert Nardelli, now heading 3M and Home Depot, respectively, remain so devoted to Welch that when he told them the bad news last Thanksgiving they felt sorry for him. As for the man Welch selected, Jeffrey Immelt, consider what he told Welch and 550 other top G.E. executives in Boca Raton last January, shortly before a farewell champagne toast to the departing chief: “Only time will tell if Jack Welch is the best business leader ever, but I know he is one of the greatest human beings I have ever met.”

So, I understand you’re going to give my book a shitty review?” Jack Welch, to whom I had never previously spoken, had just walked into the conference room off his office at General Electric headquarters in Fairfield, Connecticut. A slight man who speaks with a heavy Boston accent— Wee ah not smahtah than everyone else; we just wuhrk haahdah—he seemed very ordinary, at least here. The elements of his incontrovertible genius—his abilities to spot deals, to crunch numbers, to move decisively, to deal with other executives, to ax without angst, to teach and inspire his troops—would not necessarily be evident sitting around eating frozen yogurt with him in his office. He was dressed casually, part of his crusade against formality: no necktie, a blue striped Ralph Lauren shirt. (“We have a joint venture [selling clothing on-line] with him,” he said. “It hasn’t done that well.”) His very ordinariness puts people at ease, leaving them ripe either for persuasion or for the plucking. Once, when a meddlesome Labour government left G.E.’s turbine business in Great Britain nearly aground, Welch visited Tony Blair. It was their first encounter too. “Mr. Prime Minister, I’m in deep shit,” Welch began.

I had in fact read an advance copy of his book, and had voiced my reservations to John Byrne, who had promptly conveyed them to Welch. To me—admittedly I’m no businessman—there is too much management talk and too many General Electric names dropped in too casually, like one of those center-field scoreboards that list people attending a ball game. (One of Welch’s tenets is differentiation—the ability to separate people according to their talents—but I had trouble differentiating Ted LeVino from “Lofie” LoFrisco from Paolo Fresco.)

Mostly, though, there is not enough Jack Welch. By all accounts Welch can be blunt, crude, coarse, profane, funny. It is, as he might say, paht of his chahm, at least if you’re in his good graces. He’s a man’s man, circa 1955. While watching a game show during his first trip to NBC’s Burbank studios, a Vanna White type on the set prompted Welch to grab the arms of his tour guide and remark, “Look at the tits on that one.” But in Jack his jagged edges have been sanded down; the crooked has been made straight and the rough places plain. I felt the book lacked introspection. That word—introspection—had gotten back to Welch, and gotten under his skin. Repeatedly over that day and the next two, both in his office and at his summer home on Nantucket, Welch kept coming back to it, kept lording it over me, in a tone that betrayed hurt feelings, resentment, condescension, machismo, ridicule. It was his way of mocking what he considered to be my highfalutin, touchy-feely, pretentious, overly cerebral, effete ways.

Welch is a philistine, or likes to portray himself as one. The first paper he picks up each morning is the New York Post. He went to the opera only when his new wife forced him to; “husband duty,” he called it. He can’t name the last book he read. He is the type either to disdain foreign words or to misuse them, maybe even deliberately, e.g., “There was a part of his bon vivant and creativity that I liked.” Welch is a man of strong but few passions. They seem to number just about three: G.E., golf, and the Boston Red Sox. One colleague recalls seeing him in a particularly euphoric state. He thought Welch, the father of four grown children, had had a new baby. In fact, G.E. stock had hit a new high. Introspective, then, is something that Jack Welch never has been, nor ever wanted to be. In fact, introspection would probably have kept him from accomplishing much of what he did.

Welch says his book was never supposed to be an autobiography. “I see it more as a series of business experiences that I thought were very personal,” he says. “No one is really interested in my life.” And what there is, is all there is: “I dug as deep as I knew how to. . . . It’s everything I know about everything.” Another time, he puts it to me slightly differently: “Just remember: this is not Katharine Graham,” he says, referring to the late Washington Post publisher’s intimate 1997 autobiography, Personal History. How about the agony of running one of the world’s mightiest entities? “There ain’t that much agony! ... It’s wild, it’s fun, it’s great wine, you see great people. I mean, this job is all the nuts. This job is not agony. You get to play great golf courses. I mean, this job is not some laborious agony job. . . .We have fun.”

Welch abhors pomposity, and his book features regular spasms of self-deprecation. “I might not be the brightest bulb in the chandelier,” he writes. And: “I hate having to use the first person. Nearly everything I’ve done in my life has been accomplished with other people.” Occasionally, the modesty seems forced. More often, he succumbs to the swagger of “I Gotta Be Me” or “My Way,” and that’s probably a good thing, for it is what his readers want.

Go by your gut, Welch says: “More often than not, business is smell, feel, and touch as much as or more than numbers.” Avoid “superficial congeniality” and “false kindness”: tell people precisely where they stand. Loathe formality and never stop “kicking bureaucracy’s butt.” “Kick ass and break glass,” but if you kick, you must also sometimes hug. Keep things lean and nimble: “I tried to create the informality of a corner neighborhood grocery store in the soul of a big company.” Celebrate the small victories, and even some defeats. Favor passion over intellect or credentials.

Welch has introduced a whole vocabulary of slogans and neologisms into the workplace language. There are his Four E’s of leadership: high Energy, the ability to Energize others, the Edge to make tough decisions, the ability to Execute them. There is Work-Out, a program modeled after New England town meetings, in which employees vent freely, without regard to rules or hierarchy. There’s “runway,” a person’s capacity to grow, and “stretch,” formulating goals beyond his wildest dreams. There’s “wallowing,” Welchspeak for brainstorming uninhibitedly. And there’s the Vitality Curve, a hump on a piece of graph paper dividing the “top 20” from the “vital 70” from the “bottom 10” percent of a workforce, the first to be cherished, the second to be taught, the third—after appropriate warnings and second chances—to be lopped off without mercy.

Welch’s G.E. devotes enormous energy to spotting, evaluating, training, inspiring, and—incessantly, compulsively—grading and classifying its talent. The very variance Welch labored to stamp out in his products and services, most notably through the Six Sigma program, he cherished in his employees—dividing them into “A,” “B,” or “C” players, or “Type 1,” “Type 2,” “Type 3,” or “Type 4” managers. At times it seems that G.E. executives and managers would be too busy sizing one another up ever to produce a single lightbulb. But Wall Street felt, and knew, quite differently.

Welch grew up in Salem, Massachusetts, the only child of what were, at least by the standards of the time, aged parents. He scarcely mentions his father, a conductor on the Boston & Maine railroad. His mother—blunt and utterly devoted, convinced her little boy stuttered because his tongue couldn’t keep up with his quicksilver brain —gets most of his love. It is she who gave him his self-confidence and his pragmatism—“Don’t kid yourself, that’s the way it is,” she liked to say—and he has still not forgiven God for her death 36 years ago. Small and not a star, either athletically or academically, young Jack got by on spunk. “My parents made me feel so good about myself, but always in a way that never made me, I don’t think, a punk, a shithead,” he says.

While two of his friends got to go to fancy colleges on navy scholarships, he was turned down. He went to the University of Massachusetts, then studied chemical engineering at the University of Illinois. (His doctoral thesis was on “condensation in steam-supply systems.”) Caught in flagrante delicto with a “pretty girl” in his car shortly after he got there, Welch was bailed out by his departmental chairman, one of the many mentors and protectors he collected throughout his career. He joined G.E. in 1960—his base was Pittsfield, Massachusetts; his salary, $10,500—and, anticipating Dustin Hoffman by nearly a decade, he went into plastics.

Deftly playing both the iconoclast and the company man, he rose quickly. By 1979 he had moved to headquarters—which he had always done his best to avoid—in Connecticut. A G.E. executive who worked with him at the time recalls, “Did you ever read What Makes Sammy Run? That kind of personified Jack.” Welch conceded in a 1973 self-appraisal that he needed to improve his “ability to handle socio-political relationships.”

Welch sized up people quickly and harshly: according to the only critical biography of him, Thomas F. O’Boyle’s At Any Cost: Jack Welch, General Electric, and the Pursuit of Profit (1998), he was so down on fat employees—he thought they were, according to one former colleague, “undisciplined slobs”—that in one instance underlings hid their heavyset co-workers before Welch was due to arrive. (Not so, Welch insists: his friend Lofie LoFrisco is “very fat,” as were a number of G.E. colleagues. “The guy in tubes was huge,” he recalls. “Actually died of obesity. Great guy”)

Some of Welch’s superiors were skeptical. “Johnson thought I was too young and too brash and didn’t have the G.E. monogram stamped on my forehead,” Welch writes of one. “He thought I drove too hard for the results I got and had little respect for the company’s rituals and traditions.” But in 1980, Welch was tapped for the top job. “I’ll give him two years—then it’s Bellevue,” one G.E. executive was heard to say. His first marriage collapsed in 1987. Of the divorce, he writes simply that it was “difficult and painful.” As for child rearing, Welch writes only that he was “the ultimate workaholic.”

To all outward appearances, G.E. was in good shape. But Welch set out to revolutionize the place, and, as he says, “there are no modest revolutions.” He decreed that G.E. would stay in only those businesses in which it was either No. 1 or 2. “Fix, Sell, or Close” became his motto. Out went items forever associated with G.E.: irons, toasters, hair dryers, blenders, vacuum cleaners, television sets. It was a sea change in American culture, but with cheap imports looming, Welch had no qualms. “Never touched me,” he says. “I am sentimental. I am sentimental about the Red Sox, I am sentimental about friends in high school. . .I am sentimental about friends today. But I’m not about a business that’s going out of business. And a lousy business ends up hurting everybody.”

Along with the divestitures (which lopped 37,000 off the payroll) came the layoffs: 81,000 in his first five years on the job. Fortune put him at the top of its list of “The Toughest Bosses in America,” describing him “criticizing, demeaning, ridiculing, humiliating” his employees. 60 Minutes accused him of putting profits ahead of people. And Newsweek branded him “Neutron Jack,” which stuck, and stuck in his craw. Looking back, he says that his only regret was that he didn’t do more and fire people more quickly. “We had 425,000 people and $25 billion worth of business” when he took over G.E., he tells me. “Today we have 300,000 people, and $135 billion worth of business. Now, either we had too many people or I was Neutron Jack.”

Having gotten G.E. out of penny-ante appliances, he pushed its bigger, more profitable lines: power turbines, jet engines, medical equipment. He moved aggressively into financial services, which now account for 40 percent of G.E.’s revenues. And he began looking “for a hideaway from foreign competition.” That, and not a great love for broadcasting or journalism, accounts for G.E.’s 1985 purchase of RCA, which owned NBC. His hubris from that deal, he admits, led him to buy Kidder, Peabody, the Wall Street securities firm that was soon awash in a fraud scandal. From that moment on, he remained wary of trying to meld different corporate cultures, which explains why the company passed on several Silicon Valley opportunities.

Welch learned of Honeywell’s impending deal with G.E.’s major competitor in jet engines, United Technologies, last October, only moments before it was to close. Within minutes he faxed to Honeywell what turned out to be the prevailing bid, for $45 billion. Welch predicted the deal would sail through, and put off his planned retirement—set for April 30, 2001, five months after his 65th birthday—until everything was buttoned down. American anti-trust regulators signed off; in Washington, one G.E. rival complained, no one wanted to take on Jack Welch. But his name—and his charm—helped little in Europe; the European Commission’s chief antitrust official, Mario Monti, even refused to call him “Jack.”

In a last-ditch effort to save the deal, Welch met with Monti in Brussels last June. But to Welch, Monti’s final offer, requiring G.E. to sell off huge chunks of Honeywell, was like buying a beautiful golf course minus several key holes. “Mr. Monti, I’m shocked and stunned by these demands,” Welch told him. “If that’s your position, I’ll go home tonight. I’ve got a book to write.” At that point, he recalled, “a heavyset, round-faced German” official sitting across the table broke out laughing. “That can be your last chapter, Mr. Welch,” the man declared. “ ‘Go Home, Mr. Welch’ is a perfect title.” (And it is, in fact, the title for that chapter in Welch’s book.) Ultimately, Welch writes, he was done in by his perpetual enemies: “bureaucrats.” But to him Honeywell was “just another deal,” one he could have pulled off if he’d been concerned only about his image; real leadership lay in walking away. “Let’s get it straight, there is no law” in Brussels, he tells me. “They make it up as they go along.” (Monti declined to comment.)

In his book Welch mentions encounters with Michael Eisner, Jerry Seinfeld, Warren Buffett, Jay Leno, and Bill Clinton, but just barely. He doesn’t mention Ronald Reagan at all, even though he met him, and Reagan was a longtime spokesman for G.E. Jack, then, raises two interesting questions: What is the opposite of name-dropping? And why is there so little settling of scores? “I didn’t do a Redstone,” Welch explains, referring to the attacks—often on his “friends”—that Viacom chief Sumner Redstone indulges in in his new book, A Passion to Win. Surely, Welch must have been tempted? “That’s not true,” he says. “People dealt with me pretty straight up. I felt I always got a fair shake.”

In most cases, one has to extrapolate. “Gary Wendt was quirky, to say the least,” he writes of the former head of G.E. Capital Services. And “the least” is precisely what he says about Wendt, with whom he is known to have butted heads. Welch attacks almost no one by name, making the few instances in which he does especially jarring, and revealing.

Welch clashed repeatedly with Lawrence Grossman, who was running NBC News when G.E. took over. He does not mention how, during the stock-market crash of 1987, he asked Grossman to ban the term “Black Monday” from all broadcasts because it was depressing the value of blue-chip stocks, G.E.’s included. (Grossman says he refused.) But he writes disapprovingly that Grossman “operated under the theory that networks should lose money while covering news in the name of journalistic integrity”; that Grossman once cut short a crucial budget meeting to go see Chief Justice Warren Burger, of all people; and that he persisted with plans to hold a dinner party—with the Tom Brokaws, Bryant Gumbels, and Jane Pauleys attending, along with the Welches—during the fateful Game Six of the 1986 World Series, when the Red Sox were playing the New York Mets. “I was shocked by Larry’s insensitivity to the game’s importance,” he writes.

Welch soon concluded that he and Grossman “were on different planets,” adding, “We put up with Larry for 18 months.” As for Grossman, he agrees about the different values and the dinner party. But he insists that the financial pressures Welch imposed on NBC News soon produced “very serious trouble”—a veiled reference, presumably, to the staged gastank explosions on Dateline a few years later.

More recently, NBC News has been accused of playing down stories about which G.E. might be sensitive, most notably the one about the PCBs that G.E. poured into the Hudson River for 30 years, though at a time when it was still legal to do so. (In the mid-1970s, New York State nonetheless charged G.E. with violating state water standards, a case the company settled for $3 million. A young Jack Welch signed off on the deal.) According to Jeff Cohen of Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting, anyone watching NBC would know little about PCBs. “Whenever it involves G.E., almost no one there sticks his neck out,” he says. “The Hudson River story is made for prime time; it has visuals, victims, and a villain. It’s because of who the villain is that Dateline hasn’t gone to town on it.” An NBC report on the E.P.A.’s recent decision noted how a congressman from upstate New York, John Sweeney, was highly critical of the order to dredge. It did not note that G.E. was one of Sweeney’s largest contributors.

Andrew Lack, who led NBC News for nearly a decade until Welch tapped him recently to head the entire network, says that NBC Nightly News has done at least three pieces on the PCBs. “I’m not sure our competitors have done as much, though I’m not sure they’d be honest about it,” he says. Still, when Frederic Dicker of the New York Post railed against the E.P.A. recently on the Don Imus Show (broadcast on MSNBC), calling its ruling “a viciously anti-business decision” against “one of the greatest companies in the world,” the “I Man” was uncharacteristically mute.

Not surprisingly, no NBC news program ever booked O’Boyle, author of the critical Welch biography. Nor, for that matter, did any other network. Nor did The Wall Street Journal ever review it, even though O’Boyle had once worked there. “The publicist told me, ‘Forget it. Nobody wants to piss off Jack,’” recalls O’Boyle, now assistant managing editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. (That still seems true: recent Welch segments on Charlie Rose and 60 Minutes were very soft.) Stock analysts and business-school professors, too, are loath to criticize Welch, says O’Boyle, either because they need access to him or receive G.E. funding. Though he spent six years on his book, O’Boyle acknowledged difficulties uncovering the inner Welch, despite pressure from his editor to delve deeper. “I told him, ‘I don’t think a shark thinks too much about what it eats. It just eats,’” he recalls.

G.E. threatened to sue O’Boyle based solely on his book proposal, which it had somehow managed to obtain. Clearly concerned, O’Boyle’s publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, had three separate sets of lawyers vet the book. One person who didn’t read At Any Cost, which is to be re-released on the same day as Jack, was Welch himself, even though he writes in Jack that “self-confident people aren’t afraid to have their views challenged.” “I knew it was nasty. And I knew it was crazy. Why would I want to read that?” he remarks to me.

Welch describes himself as “socially a Democrat, fiscally Republican,” but says he hasn’t voted for a Democratic presidential candidate since Lyndon Johnson. He says he liked Clinton even though, after appearing to listen to him closely and actually taking notes as Welch talked, the then president ignored all his advice. But Welch positively loathes Al Gore, perhaps because Gore embodies the elitist, intellectual environmentalists he detests. At a New York dinner party earlier this year, Welch shocked his fellow guests (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts chief Henry Kravis, Quadrangle Group founder Steven Rattner, and former U.N. ambassador Richard Holbrooke among them) by describing Gore as “evil, evil, evil.” “It was like for a minute the veil was ripped, then he got himself under control and resumed the charm offensive,” one guest recalls. Does he really consider Gore “evil”? “I don’t think he’s evil,” Welch tells me. “He seems to have a charming wife and family.” But had he said it? “I’d prefer not to comment.”

Shortly after last fall’s vote, rumors began circulating that Welch, hanging out in NBC’s control room on Election Night, had cheered as states were called for Bush, hissed when they went to Gore, and asked the men supervising computer projections, “What would I have to give you to call the race for Bush?” In hearings held last February, Representative Henry Waxman of California asked Lack whether Welch had interfered. “It’s just a rumor, a dopey rumor,” testified Lack, who promised that if a tape had in fact been made by NBC’s promotional team, as Waxman had suggested, he would provide it. Lack has since backed off that pledge—the First Amendment, you know—and Waxman is threatening a subpoena.

“This is such a crazy story. To think you could ever influence two old pros who wouldn’t call an election for anyone if their life depended on it ... it’s just silliness,” Welch laments. “The facts are there was a room there of young kids all cheering for Gore, and two or three of us cheering for George Bush. That’s all that happened.”

'Think of yourself as a great brand,” Robert Rubin, the former secretary of the Treasury, recently advised Jack Welch. “Don’t do anything to hurt it.” And Welch isn’t. He plans to spend most of his time quietly offering business advice to a handful of clients, whom he has already selected but won’t identify. How completely will he butt out of G.E.? “One hundred and one percent,” he says. Another thing he says he will not do is buy a piece of the Red Sox, as had been reported. Handling salary caps, negotiating contracts, dealing with the press: all, he says, would take the romance out of the team, which he has been following since Ted Williams roamed Fenway Park’s left field.

The Welches are now building a newer, smaller house in Connecticut. But when the weather turns warm they will still go to Nantucket, a 25-minute flight from Bridgeport. The salt air, the accents, the lobster rolls, the Globe on the newsstands, the Red Sox on the radio: all are part of Welch’s childhood. He describes his home on the island, a handsome, multi-angled Colonial-style structure with the usual weather-beaten cedar shingles, as “the house I built when I had no money.” Twenty-five years ago, he paid $70,000 for the five-acre spread. Nantucket is now officially “hot,” and when he added six adjacent acres recently, they cost him $4 million more.

From the front yard he can see them hitting. The golf players, that is. If he has a religion, it’s golf. (Though he is friendly with New York’s Edward Cardinal Egan, aiding his charities and attending his investiture in Rome, Welch, the former altar boy, is no longer observant.) He learned the game as a caddy back in Salem, earning $1.50 for every 18 holes. He is good—he once beat Greg Norman—and compulsive: while the rest of the world tuned in to hear the verdict in the O. J. Simpson trial, Welch was intrepidly leading 170 G.E. executives out for 18 holes at Blind Brook Club in Purchase, New York. The golf course is where Welch formed some of his most enduring friendships. It is also where, he says, he learned some important lessons about life. “I got a very early look at how attractive or how big a jackass someone can be by watching their behavior on a golf course,” he writes.

Welch is a two-time course champion at Sankaty Head Golf Club on Nantucket; he says his game improved while he was teaching it to his second wife, Jane, a spirited Alabama-born lawyer 17 years his junior. (The two were fixed up by Walter Wriston, the former head of Citibank and then a member of G.E.’s board, and his wife, Kathy.) Now she’s a club champion, too.

Welch is a social creature. He says he did not choose oceanfront property here because he prefers seeing twinkling lights at night to staring out into the void. But he and his wife don’t go out much on Nantucket. “Look how alone we are here,” he says contentedly, standing on the porch, the waters of Sesachacha Pond and the Atlantic Ocean beyond. “You don’t get to feel this way in a lot of places.” Evenings are for watching movies, largely videos from Sumner Redstone’s greatest hits: the American Film Institute’s top 100 films of the 20th century, which Redstone’s Blockbuster has packaged and Redstone gives as gifts. The fare is simple: Orville Redenbacher Lite popcorn and a good bottle of Bordeaux—a Lafite or Margaux or Haut-Brion, from ’82 or ’86 or ’89. “It sounds pompous, but I vowed after my surgery that I’d never drink another inexpensive bottle of wine,” Welch explains.

One night in late July over dinner at the Nantucket Golf Club—Sankaty Head’s newer, posher counterpart—Welch got the urgent call about the E.P.A. ruling. He disappeared for a while, long enough for his tomato-basil soup to grow cold. When he came back, having heard that G.E. had lost, he seemed oddly unperturbed. “This has been a lot of years,” he said to me wearily. “If you were surprised by this, you should be arrested.” He said G.E. is “paying the price for Kyoto and arsenic,” referring to much-criticized Bush-administration decisions to oppose the treaty on global warming and approve higher levels of arsenic in drinking water.

Welch likes the president—“Dubya is a good shit,” he says—and admires his family; not surprisingly, he has played golf at Kennebunkport. But “the politics of the current administration are now going to make it tough to make a logical decision,” he says. With George Bush suddenly going green, even G.E.’s formidable array of Washington lobbyists, including former Maine senator George Mitchell and Robert Livingston, former chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, proved powerless. It is also clear, though he didn’t quite say so, that Welch feels Whitman and New York governor George Pataki, who also supports the dredging, are pandering for votes rather than acting out of any convictions. A spokesman for Pataki, however, insists that a full and comprehensive cleanup is “sound science ... based on any number of studies and reviews.” He also notes that the governor grew up along the banks of the Hudson.

Welch maintains that PCBs don’t cause cancer but, in any case, should be left where they are, buried under layers of sediment. Dredging them, he argues, will only repollute the river. “I think it’s a disaster,” he says of the ruling. “I mean, the money, we can donate it to schools. As a matter of fact, if they want to punish us, they can come up with a thousand things to do. But not dredge the river the way they want to.” Many local residents agree, albeit only after G.E. spent tens of millions of dollars to convince them. Welch felt trapped while recording Jack on tape, but is said to have gotten all revved up reading his chapter on PCBs. Proponents of dredging see G.E.’s position a bit differently. They say the company is digging in its heels not out of principle but because acknowledging its responsibility for the Hudson will subject it to billions of dollars in cleanup costs for toxic sites elsewhere. In fact, the company has gone to the U.S. Supreme Court to challenge the Superfund law under which the E.P.A. is acting, hiring Harvard law professor—and former Al Gore lawyer— Laurence Tribe to argue its case.

Had Welch needed any shoulders to cry on that night at the country club, he was in the right place. G.E. types tend to stick together, whether in Fairfield or Palm Beach or Nantucket, and the dining room was crawling with current and former G.E. brass. Welch introduced me to Larry Bossidy, who now heads Honeywell. “He’s writing about introspective things,” Welch said, pointing to me. “Well, if you find anyone who’s introspective, it will be the first time,” Bossidy wisecracked. Later, Art Puccini, the G.E. executive who negotiated the original deal with New York State over PCBs 25 years ago, came over. He put his arm around Welch, congratulated him on his retirement, and then, after a moment’s hesitation, leaned over and kissed him on the cheek. “Isn’t it nice?” Welch said. “We’re all like family.”

At the risk of demanding excess introspection, I ask Welch whether, if he could live his life all over again, he would do it all the same. He says he would. “Whether right or wrong, I made a lot of people reach beyond what they thought their capacities would be, to find themselves, to do more,” he says. But when all is said and done, does he like himself? “I’m kinda pleased,” he says. “I think I’m a pretty good guy.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now