Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

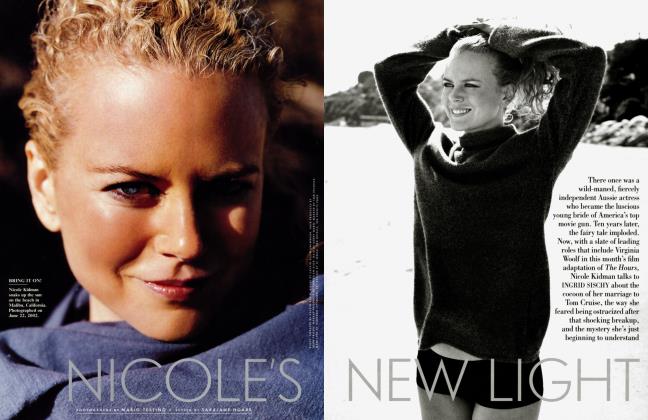

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDE PALMA AND THE WOMEN

JAMES WOLCOTT

Brian De Palma may be America's greatest living director, yet he gets almost none of the tributes accorded such peers as Scorsese and Spielberg. Semi-exiled in Paris, he's giving his critics another chance to see what they've missed, with Femme Fatale, a brilliantly noir European chick flick

A case could be made—so why not make it?—that Brian De Palma is the apex predator of American directors, perhaps our greatest living filmmaker. He is undoubtedly the least appreciated. Born in 1940, raised in Philadelphia, De Palma had a ringside seat at the operations performed by his father, an orthopedic surgeon. It was in these tender, formative moments that he developed his keen interest in the fine art of human-parts removal. Majoring in physics at Columbia University, he got the theater bug and took up drama, shooting 16-mm. film shorts. Since the release of his first feature, Murder a la Mod, in 1967 (he did an earlier film which surfaced later), De Palma has nosed through our dampest secrets and nightmares, his camera devouring everything before it, digesting on the run. In a telephone interview, De Palma describes himself as someone who "grew up in an era of stunning visual stylists" and now finds himself wondering where everybody went. "Few directors are practicing this," he says, "this" being "pure visual storytelling." Utilizing split screens, instant replay, rhapsodic slo-mo, multiple points of view, and the hovercraft abilities of the Steadicam (a camera that floats and sharks through the air, pursuing figures who themselves seem composed of air), De Palma demonstrates in film after film that reality is simply a rough draft, subject to tricky memories, evidence tampering, drastic re-editing. His prodigious output of 25 features in 33 years is a virtuoso gloss on the old punch line "Who are you gonna believe, me or your lying eyes?" (Snake Eyes deconstructs the footage of a televised assassination to crack open an act of mass deception, a cunning pantomime.) Like his favorite ghost, Alfred Hitchcock, he enjoys playing pranks on the audience that deliver the sting of mortality. Moments of beauty reveal blight at the full arousal of their bloom. Lyrical interludes end with a sprung-trap snap—the hand grabbing from the grave to uncork one last scream in Carrie.

Yet nothing he's done previously prepares us for the voluptuous epiphany in his new movie, Femme Fatale, when Rebecca Romijn-Stamos plunges daggerlike into water and her clothes magically vanish, her nude body embroiled in blue bubbles. Arms outstretched, feet pointed, her aquatic pose suggests a sexy pinup takeoff on Andres Serrano's Piss Christ, crystallizing the movie's sacred and profane intersection of baptism, crucifixion, and resurrection. Full of amazing plenty, De Palma's amoral morality tale is a study of redemption photographed like a Victoria's Secret catalogue, blood drops providing the cherry topping on creamy-vanilla skin trimmed with lace. It's the work of a cheerful, horny man. An anomaly these days.

Which may help explain why De Palma has never earned the honors accorded his peers—his snarky cynicism, hedonism, and jack-in-the-box humor make him seem unserious, lacking in the gravitas that is supposed to go with gray hair. Joker that he is, it's a bad rap. When De Palma has bared the passion of his convictions—in the grief-choked denouement of the conspiracy melodrama Blow' Out, his darkest exploration of the politics of perception, and the vale-oftears Vietnam drama Casualties of War— he has been rejected at the box office and snubbed by the tooth fairies who dole out prizes. Like Hitchcock, he has never won an Academy Award for best direction. Of all the 70s directors to storm the pantheon, De Palma is the one most lacking in name-drop cachet, official stature, even minor-celebrity recognition (this, despite wearing a trademark safari jacket for decades: Call me bwana). Martin Scorsese, capable of doing an encyclopedic speed-rap on any director past or present, has become cinema's chief curator through his tireless dedication to film preservation; Steven Spielberg and George Lucas reign as cinema's technocrat aristocrats and visionary entrepreneurs, wedding multiplex franchises to mass merchandise (Spielberg is also becoming fit for a pedestal as a philanthropist); Francis Ford Coppola, tending to his vineyards, is the proud paterfamilias, casting a bulky shadow over a directorial dynasty that includes daughter Sofia (The Virgin Suicides) and son Roman (CQ); Robert Altman is the grumpy maverick, granted old-master status after putting a pedigree cast through their paces in Gosford Park; and Peter Bogdanovich, beating out stiff competition as the most pompous fathead in Peter Biskind's 70s film history, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, received a fond pat from the film community for The Cat's Meow, a valentine to pretalkies Hollywood. Only De Palma has been dumped into the laundry hamper. As he noted in a recent interview, his films have toured the festival circuit worldwide yet never made the slate of the New York Film Festival. "Now there's the irony, that I've never been invited to premiere one of my movies in my hometown festival."

For reasons he can't fathom ("I don't know what I'm doing that's making them so mad," he told me), Brian De Palma is the only artist in his field still being penalized—stigmatized—for the violence of his work. It's as if he's inherited the late Sam Peckinpah's Devil's horns. No denying he's spilled more than his quota of red quarts over the course of his career. The pig's blood dumped on Carrie at the prom; John Cassavetes detonating like a human grenade in the climax of The Fury, turning the screen into a splatter canvas; the chain-saw amputation that opens Scarface and the baroque massacre that ends it (a Verdi opera performed with assault weapons); and the razor-slashing in Dressed to Kill, to name just a few hearty moments, have all helped groom the plausible impression of De Palma as de Sade's darling boy. But if devising ingenious methods of drilling for gore damned a director, he'd have a lot of company on the elevator down. Instead, he rides alone. Scorsese managed to redecorate the wallpaper with ketchup in Taxi Driver, squash a head like a melon in Casino, and dial up a world of pain in his lurid remake of Cape Fear without permanently spotting his nice suits. Critics continue to avert their notepads from the cruel stratagems in Spielberg's work, how he puts the sick squeeze on us for our own good. No one crosses the street when they see carnage specialists John Woo, Robert Rodriguez, or David Fincher approaching (and Fincher's Seven was as gruesome as a botched operation). The DVD release commemorating the 10th anniversary of Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs, with its infamous torture-interrogation van Gogh ear slice, was a downright jolly occasion. So what gives?

The difference is that these mayhem artists primarily purvey the violence of men against men locked in mortal combat over money, broads, bragging rights, and local turf—the never-ending battle for numskull supremacy. In De Palma's thrillers, women are the targeted victims. His camera teases, caresses, and prolongs the foreplay leading to the coup de grace, creating complicity between viewer and on-screen stalker, violating the no-fly zone of aesthetic distance. By following the Hitchcockian strategy of shooting his murders as seductions and his seductions as murders, De Palma stands accused of uniting violence and voyeurism, converting pulp into porn, porn into pulp. Some were especially creeped out by how he served up his then wife, Nancy Allen, as a tasty morsel in Blow Out and Dressed to Kill, as if putting on his own marital peep show (others of us thought it was nice of him to share). The critic Veronica Geng dissented from the consensus, contending that he decoupled sex and violence in Dressed to Kill, depicting violence as a shocking, unnatural invasion of the erotic sphere. But the prevailing opinion was that De Palma objectifies women in order to undress and stick pins in his Barbie dolls.

Big pins. Images of impalement recur in De Palma's films. Impalement can be interpreted as a phallic thrust of aggression, a symbolic rape resulting in fatal penetration. I was at the catastrophic public screening of Body Double where the audience hissed the notorious low-angle shot of a power drill pointed at a supine woman's body like a steel penis. The image was such a blunt provocation that one suspected De Palma might have been baiting the feminist activists who had urged a boycott of Dressed to Kill by upping the ante, saying, in effect, "You thought that was bad?—this'll really get you hopping." If so, it was a foolish miscalculation on his part (he later admitted as much). The hisses switched to boos as the drill bored a hole into the victim and through the floor below, and the drubbing De Palma later took in the press sealed his reputation as "the most vicious womanhater in Hollywood today" (Ms.). It's an ogre image that dogs him still, despite Pauline Kael's championing of Casualties of War, with its unflinching depiction of a Vietnamese captive's rape ordeal, as a feminist statement—an anguished cry for mercy and justice. Audiences avoided Casualties of War—\l was perceived as too much of a downer—and De Palma failed to clear his name with those who had mounted his moose head next to Norman Mailer's in the macho Hall of Shame.

De Palma demonstrates in film after film that reality is simply a rough draft.

The movie he directed after Casualties of War nearly wiped him off the map. In 1990, De Palma began filming The Bonfire of the Vanities, based on Tom Wolfe's best-selling novel, which trained a warped monocle on the greed, social climbing, tabloid hysteria, and race-card opportunism of Manhattan in the decade of AIDS, Donald Trump, and taffeta poof skirts. Having made his hoofprint in Hollywood as a horrormeister, De Palma was a curious, controversial choice to direct Wolfe's Hogarthian extravaganza. True, two of his early films, Greetings and Hi, Mom!, were shaggy, countercultural satires ("Greetings must be one of the first movies to take the graffiti generation for granted," Wilfrid Sheed noted in Esquire)', Phantom of the Paradise swung crazily from the rafters; and most of his whiteknucklers unsheathed feline moments of sardonic humor. However, "straight" comedy tended to lock De Palma into literalmindedness. His is a visual, not worldly, sophistication. He had never ungloved the Lubitsch touch required to steer Wolfe's sugar pops and "social X-rays" across a crowded room where the slightest faux pas could trigger a ripple effect, setting off landslides among the face-lifts. The casting also raised caution flags. Tom Hanks seemed too affably normal to play Sherman McCoy, crafty Wall Street bond trader and "Master of the Universe," and rewriting the British hack-journalist character into a role for Bruce Willis and his smirk smacked of idiot expediency. To dampen racial friction, the producers also performed an identity transplant on the crusty Jewish judge in Wolfe's novel, changing him into a black Solomon worthy of Morgan Freeman's noble enunciation. This wasn't enough to placate those who believed that Wolfe, a southern dandy in plantation white, peddled cartoon stereotypes, depicting a wrong turn onto the Bronx's mean streets as a detour into darkest Africa. The production became a battle zone of picket signs and location scrambling. It was also an expensive production: one of the movie's most spectacular shots—the Concorde hazily materializing in an orange sky like a glider mailed from the future—cost more than De Palma's first three films combined.

History shows that a great movie can emerge from the volatile mixture of egos on a troubled set (prime example: Sweet Smell of Success, where clashes by day produced a jazzy classic by night). This, however, would not be a triumph of alchemy. A mighty egg was laid. The Bonfire of the Vanities turned out to be one of those fiascoes at which even the prophets of doom did a double take. "Bombfire of the Vanities," the film was christened. Ishtar was invoked. The almost universally scornful reviews left whip marks on the director's hide. Even De Palma loyalists such as Kael handled the film with tongs, setting it aside as a regrettable lapse. The movie was D.O.A. at the box office. As Julie Salamon writes in The Devil's Candy, an inside account of the making of the mess, The Bonfire of the Vanities wasn't the only chariot to crash that Christmas season. "Clint Eastwood didn't bring audiences to The Rookie, nor did Sean Connery and Michelle Pfeiffer to The Russia House, nor did Robert Redford to Havana. Indeed, in box office terms, Havana was a bigger disaster than Bonfire. " Yet De Palma's crash site was the one circled by buzzards. And although the director himself is drawn sympathetically in Salamon's book, its publication completed the double whammy to his morale and standing, reminding everyone all over again of how he had fumbled the ball, putting his humiliating setback on permanent record.

He enjoys playing pranks on the audience that deliver the sting of mortality.

"You can't imagine what a disaster that was," De Palma told Le Monde earlier this year. "I'd adapted a sacrosanct bestseller, a monument of American literature, and it bombed at the box office. I remained the guy who had made Tom Wolfe look ridiculous, and the critical establishment never forgave me for that." Although De Palma would go on to immortalize Tom Cruise doing heroic jawclenching calisthenics in Mission: Impossible (a movie I persist in loving, the courtly presences of Kristin Scott Thomas and Vanessa Redgrave bestowing grace notes absent from the Woo-directed sequel), his studio address was still the doghouse. The crushing derision that greeted his space odyssey, Mission to Mars—in Afterglow: A Last Conversation with Pauline Kael, the retired critic expressed bafflement over how blindly the movie was received ("About half of it is superb, and I can't understand why more people didn't recognize that")—revived the embers of Bonfire's, debacle. He awoke from the expensive demise of Mission to Mars to find the scarlet letter L—for Loser—sewn onto the pocket of his safari jacket.

Two years ago, De Palma beat a tactical retreat to Paris, that refugee camp for orphaned artists, where he needn't fear schoolchildren taunting him on the streets for lousy Variety grosses. Unlike most American critics, ingrates too busy eavesdropping on one another in the lobby to formulate their own responses, French film nuts appreciate personalized tapestries. A retrospective of his films attracted full houses at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and French rappers sample Scarface for street cred. Meanwhile, back home he couldn't be more passe. "In the United States, I'm washed up," he informed Le Monde. "I'm the biggest subject of ridicule after Jerry Lewis."

'Washed up" isn't a throwaway phrase. It's a Freudian clue. Femme Fatale, his first film since making the partial break from America (he divides his time between Paris and his apartment in New York), is drenched in water imagery: a gothic rainstorm, a long bathtub soak, an overflowing aquarium, a dive into the river Styx. The movie is a platform leap into Brian De Palma's state of mind, an allegory for an artist's sinking, near drowning, and splashy resurfacing. Opening with a nude odalisque reflected on a hotel-room TV screen showing Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, their images overlapping (the first of many doppelganger ploys), Femme Fatale announces its creator's intentions when a hood named Black Tie (Eriq Ebouaney) whips open the curtains and spread out below is the red carpet for a gala screening at the Cannes Film Festival. Superimposed on this flashbulb-popping parade of French celebrity is the credit DIRECTED BY BRIAN DE PALMA, De Palma's way of declaring, "Take a look—this is my new playground."

The odalisque dragging herself off the bed is a jewel thief named Laure Ash (Romijn-Stamos, who also plays Lily, the suicidal woman whose identity Laure later assumes). She's part of a crew planning to steal a $10 million diamond-studded solidgold serpent wrapped as body jewelry around the date accompanying the director of the Cannes entry. As the date, Veronica (model Rie Rasmussen) is the strutting embodiment of forbidden desire, an R-rated Eve entwined by the Garden of Eden's snake, and the movie takes its rhythm from the high-heeled click of these two lithe beauties treating the corridors of the cinema as converging catwalks. A Camille Paglia ode to pussy power made flesh, one deity is blonde, the other brunette; nature dictates that they mate. Laure lures Veronica into the ladies' room of the cinema, separating her from her male bodyguards, and without so much as a bonjour the two of them proceed to glue their bodies together as if someone rang a bell.

As the notables (among them actress Sandrine Bonnaire) settle into their seats for the screening of East/West, whose stark opening shot is a witty distillation of typical festival fare, the two hotties engage in a fast and furious long-limbed lambada. (According to Romijn-Stamos, De Palma lightened her concerns about doing the scene by "casting a friend of mine as per my request." That's one of the upsides of being a supermodel, knowing you can count on a supermodel pal to assist in an on-screen lesbian scorcher.) A panting Laure strips the body jewelry from a panting Veronica piece by piece, each segment replaced with a replica slipped under the stall by Black Tie. The absurd impracticality of this larcenous tryst doesn't slacken its excitement (De Palma demonstrated in Body Double that simulated sex has a disco beat that bypasses the brain), pleasure and tension building to a mutual crescendo as the movie intercuts to activity in every corner of the theater, which is beginning to arrow in on that steamy bathroom stall. Scored to a toned-down variation of Ravel's "Bolero," the tempo of the action racing as if too antsy to wait for the soundtrack to achieve rapture, Femme Fatale's 15-minute multicomponent set piece, with its seduction, heist, double cross, and narrow escape, will send cinephiles into categorical bliss. A minimasterpiece, it's so meticulously crazed that you want to pause the film, rewind, and watch it again.

Femme Fatale is the work of a cheerful, horny man. An anomaly these days.

Like Hitchcock in North by Northwest, Howard Hawks in The Big Sleep, and Pedro Almodovar in his early sex farces, De Palma plays loose and fancy with plot logic in order to follow the wicked bounce of his own inclinations, twirling up each scene into a goody bag of eye candy. "A noir story bracketed in a dream," in De Palma's words, Femme Fatale seems to have a homing device planted on its cool blonde, tailing her in long, seamless, wordless sequences through the streets and interiors of a Paris that looks airbrushed of tourists and nonessentials, an abstraction of itself, like Woody Allen's Manhattan. Instead of the usual international clamor of ads and logos, the posters pasted on walls and kiosks are figments of that dream, mind tricks. The whole movie is an elaborate, playful trompe l'oeil. Antonio Banderas plays a repentant paparazzo who's assembling a Hockneyesque collage of the view from his balcony—utilizing a split-screen scene, De Palma sets the collage and the real view flush against each other to give the illusion of Laure stepping out of her own zoom shot. What keeps Femme Fatale from being a clinical game board of optical gimmicks is the pallor of Eurotrash glamour that Romijn-Stamos flaunts, commanding every scene as if it were a private suite. Her no-nonsense, nicotine line delivery is very noir, very funny, and, despite the bitch of a character she plays, strangely likable. When Banderas's photographer pours tender nothings into her ear as he's servicing her from behind over a pool table, she responds, "That's so sweet .. . that's so romantic," in the toneless voice of a call girl counting down the seconds until liftoff. Like Stanwyck's two-timer in Double Indemnity, Laure is a cold user—bad, real bad, rotten bad—but Romijn-Stamos imparts an extra Karma-chameleon quality to her sullen poses that gives her character a shiny patina. The most iconographically charged moment in the movie comes when Laure appears with her head wrapped in a silk scarf, wearing sunglasses to cover a bruised eye, looking like Grace Kelly, Jackie O., Audrey Hepburn, and Princess Diana fused into a supercomposite sacrificialgoddess cover girl. But the bruise is fake, the badge of victimhood a ruse, and Woman the ultimate winner in Femme Fatale, the first chick flick for continentals.

I still have the file folder Pauline Kael once sent me containing the original reviews of Carrie. Rereading them was a revelation, one reputable critic after another (Kael herself and Frank Rich being exceptions) snidely dumping on a film recognized today as a pop classic and the sister source of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, their eyes shut to its humor, incendiary force, formal design, and teenage-angst pathos. The yellowed clippings are punctuated with Pauline's exclamation marks in the margin, her silent yelps of disbelief. Prediction: in years to come, Brian De Palma's most beautiful unfoldings on film (Blow Out, Casualties of War, Femme Fatale, the best moments of The Fury, The Untouchables, Carlito's Way, Snake Eyes) will be as esteemed as Carrie. The French aren't always wrong. Jerry Lewis is a genius. So is the guy in the safari jacket.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now