Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE FILM SNOB'S DICTIONARY VOL. 2

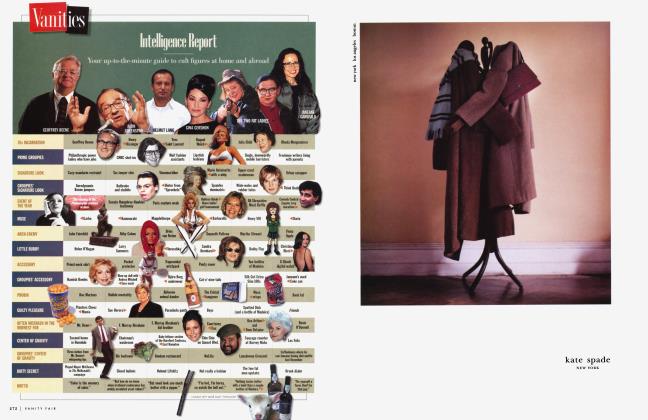

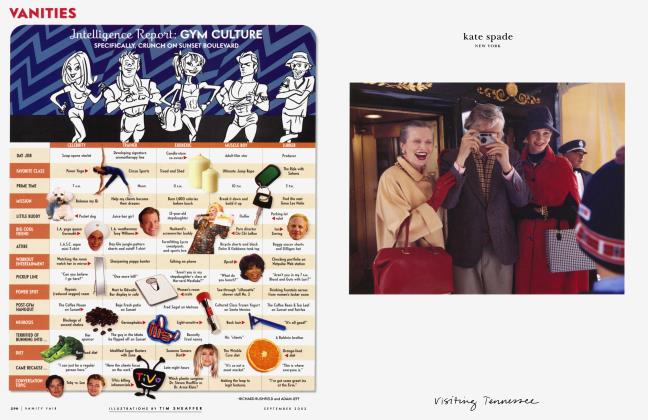

VANITIES

(NOTE: As in the previous edition of this dictionary, cross-references to other entries are spelled out in CAPITAL LETTERS. Crossreferences to items in last year's edition appear in RED CAPITAL LETTERS.)

Are you the odd man out in your friends’ bull sessions about Dolemite and Mexican wrestling pictures? Are you unable to keep the Kuchar brothers straight from the Shaw brothers? Are you baffled by your cinéaste pal’s assertion that the real star of Apocalypse Now is neither Martin Sheen nor Marlon Brando but someone named Walter Murch? Well, whoa there, don’t go all John Milius-just keep your cool and read...

STEVEN DALY

DAVID KAMP

Ai No Corrida. High-toned Japanese skin flick from 1976, featuring actual intercourse, that dragged pornography from the GRINDHOUSE to the art house. Putatively the story of a 1930s brothel servant’s affair with the madam’s husband, the film legitimized the Snob’s furtive desire for smut by allowing him to watch coitus out in the open under the guise of taking in “a study of desire.” In the U.S., the film carried the repertory-cinema-friendly title In the Realm of the Senses, rather than the direct translation, Bullfight of Love.

AIP. Commonly used shorthand for American International Pictures, a crank’em-out production company, founded in 1954, that was among the first institutions to be exalted as a font of Important Kitsch; as far back as 1979, AIP was the subject of an adoring retrospective at the Museum of Modem Art. Unabashedly chasing the whims of fickle teens, AIP’s mandate switched from Westerns (Roger Corman’s Apache Woman) to “teen horror” (I Was a Teenage Werewolf) to Vincent Price’s “Poe” movies {House of Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum) to the Annette-and-Frankie “Beach Party” movies—though, in later years, AIP’s output skewed ever more exploitatively toward GRINDHOUSE fare (e.g., Pam Grier in Black Mama, White Mama). Kutcher exudes the bland hunkiness of a juvenile lead in an old AIP feature.

Altering Eye, The. Must-have Snob book, first published in 1983, that offers a cogent but sawdust-dry analysis of the modernist film movements in Europe and Latin America from ITALIAN NEO-REALISM onward. Long a knapsack staple, the book has now been posted on the Web in its entirety by its author, Robert Kolker, a professor of film studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Anger, Kenneth. Hollywood-reared child actor, ne Kenneth Anglemyer, turned trashcinema auteur. Falling under the spell of Aleister Crowley, the suave English occultist, Anger, upon reaching young adulthood, took to making homoerotic, crypto-Fascist shorts such as Fireworks (1947) and Scorpio Rising (1964)—the latter a locus classicus of gay-biker chic, and a harbinger of Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino in its juxtaposition of jukebox pop and ultraviolence. Still, Anger is best known as the author of Hollywood Babylon, his over-amped 1960 compendium of scabrous Tinseltown gossip.

Cinefile. The premier Film Snob video shop in Los Angeles (located on Santa Monica Boulevard off Sawtelle), specializing in obscure DVDs and outof-print videos; where embittered would-be Quentins go to rent extremely rare super-8 kung fu pix and old DOLEMITE movies.

Doc Films. The film society of the University of Chicago, founded in 1932 as the Documentary Film Group. Hard-core beyond words and lay comprehension, the society is populated by 19-year-olds who have already seen every film ever made, and boasts its own Dolby Digital-equipped cinema and an impressive roster of alumni that includes Snob-revered critic

Dolemite. Cinematic alter ego of Rudy Ray Moore, a pudgy, vainglorious stand-up comic who established his own subgenre within the 1970s blaxploitation movement. The title character of his “Dolemite” films was a foulmouthed, cunnilingus-obsessed lady-killer in pimp attire who annihilated his nemeses with kung fu moves and withering jive and compulsorily revealed his large buttocks in sex scenes. An unusual crossover figure, Moore is hailed by both melanin-deficient trashfilm geeks and hip-hoppers such as Ice-T and Snoop Dogg, who consider him an influence on gangsta rap.

Downey Sr., Robert. Hippie-cinema stalwart and father of likable, albeit frequently indisposed, namesake actor. The senior Downey specialized in whacked-out sociopolitical satires suffused with stoner mischievism—Putney Swope (1969) depicted a black militant’s accidental appointment as head of a Madison Avenue ad agency, while Greaser’s Palace (1972) was a Christ parable centered on a Wild West songand-dance man. Though these films, like so much cinema of lysergic vintage, are now borderline unwatchable, they remain viable as Snob name-drops.

Ealing Studios. English film company best known for its clipped, clever-clever comedies of the late 40s and early 50s, many of which (Kind Hearts and Coronets, The Lavender Hill Mob, The Ladykillers) starred Alec Guinness. In their drollery and amphetamine-quick pacing and dialogue, Ealing comedies prefigured and directly influenced the Beatles and Monty Python. In 1988, an indebted John Cleese exhumed the elderly Ealing director Charles Crichton to direct A Fish Called Wanda.

Farber, Manny. Beloved alter kocker film critic emeritus, now working as a painter in Southern California. Preceding his friend PALI IM K by more than a decade as a nonconformist thinker about movies, Farber got his start writing reviews for The New Republic in the 1940s and proved as comfortable deconstructing Tex Avery cartoons and DON SIEGEL genre exercises as he was evaluating the French New Wave and Rainer Werner Fassbinder—in effect, inventing the prevailing critical vogue for high thought on low entertainment. A big influence on Snob-revered critic JONATHAN ROSENBAUM, Farber, more than Kael or Andrew Sarris, is the name to drop for instant Crit Snob credibility.

Freaks. Genuinely aberrant studio film from 1932, directed by Tod Browning for MGM, that featured malformed sideshow folk (including pinheads, Siamese twins, and an armless, legless man known as “the Living Torso”) as the cast in a plotline about a traveling circus whose comely trapeze artist meanly manipulates an amorous midget, only to get her gruesome comeuppance. Renowned among cultural-studies dorks for the number of “pop” references it produced, including the Ramones’ “Gabba gabba hey!” cry (an approximation of the affronted freaks’ chant) and Bill Griffith’s Zippy the Pinhead cartoon character (based in part on Schlitze, the male pinhead who padded around in a housedress).

German Expressionism. Multi-media post-World War I artistic movement whose film arm specialized in spooky, histrionic, atmospheric horror flicks— such as Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, Fritz Lang’s M, and F. W. Mumau’s Nosferatu—that, despite the heavy sanctity with which they’re treated by Snobs, are actually entertaining. German Expressionism was a huge influence on film noir in its use of shadow and light, and on Tim Burton in its grotesquerie, revelry in artifice, and general MOVIENESS.

Grindhouse. Posthumously coined genre term for the tawdry scuzzploitation films that flourished in sticky-floored adults-only movie houses before the advent of videos and the tidying up of Times Square. Though some film theorists extend grindhouse’s reign back to the anti-syphilis scare films of the 1930s (and even lump Tod Browning’s FREAKS into the category), slumming Snobs associate grindhouse with the late 60s, early 70s golden era of w.i.p. (women-in-prison) films and the deathless “classics” I Dismember Mama, Gutter Trash, and lisa, She Wolf of the SS.

Howard, Clint. Cult actor with squeaky voice and enormous cranium, best known for his brief appearances in the movies of A-list older brother Ron, though more regularly employed in TV shows and B pictures, often as a Deliveranc-esque hillbilly threat. Like Ron, Clint acted as a child, notoriously starring, at age seven, in one of the oddest Star Trek episodes ever, “The Corbomite Maneuver,” in which he played a babylike alien, mouthing words spoken by an adult actor.

Italian neo-realism. A movement that emerged at the tail end of World War II that was characterized by realistic portrayals of the lives of the lower classes and the use of non-actors and authentic locations. Though its touchstone texts, Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief and Roberto Rossellini’s Open City, are moving, their spareness makes them tough going to sit through, and the movement was quickly eclipsed, in the estimates of Snobs and ordinary Italians, by the emergence of CTNECTIT\-STYLE extravagance and decadence.

Jackson, Peter. New Zealand-born director whose stewardship of the Lord of the Rings trilogy has eclipsed his true Snob credentials as the gonzo creatordirector of Bad Taste (1987), his micro-budget splatter-comedy debut, which unexpectedly made a splash at Cannes, and its two follow-ups, Meet the Feebles (a 1989 satire of show business enacted entirely by filthy-talking, drug-taking puppets) and Braindead (an ultra-violent 1992 zombie flick, released in America as Dead Alive).

Kuchar brothers. Twin filmmakers (Mike and George, bom in 1942 of Bronxtenement pedigree) whose low-budget, high-camp films pre-dated John Waters’s and were more nai'fish and insouciant than those of their contemporaries, Andy Warhol and KENNETH ANGER, making them the semi-unwitting darlings of the 60s New York underground. The brothers are still active today, though more on solo projects than joint ones. I can’t decide if I should go to the Kuchar brothers retrospective or the Lisa Cholodenko double feature at the Queer Arts Festival.

Langdon, Harry. Baby-faced star of 1920s TWO-REELERS who briefly ranked among the comic greats (alongside Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton) but died in 1944, semi-forgotten and in reduced circumstances, thereby setting himself up to be posthumously rehabilitated by taking proto-Snob college students during the silent-comedy revival of the 1960s. Langdon earns further Snob points for having been Frank Capra’s conduit to the big time, starring in Capra’s first two features, The Strong Man (1926) and Long Pants (1927), before getting a swelled head, dismissing Capra as his collaborator, and proceeding to flounder as his own writer-director.

Luddy, Tom. Extremely socially active film archivist, producer, and festival organizer, based in Berkeley, California. Having run the Pacific Film Archive, worked at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope, and produced such off-center 80s films as Barfly and PAUL SCHRADER’S Mishima, Luddy is known for being awesomely well connected in the art-house world, and for facilitating connections among film people, art people, critics, and leftist culturati the world over. / was introduced to Fassbinder by Tom Luddy at a party at Francis’s.

Meditation on. Stock hack-crit phrase used to bestow an air of erudition and gravitas on both the critic and the film he is reviewing. Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation is an affecting meditation on cultural and temporal dislocation; the Matrix series is the Wachowski brothers’ meditation on the intersection of technology and spirituality.

Mexican wrestling pictures. Bizarre trash genre of the 1960s in which masked Mexican wrestlers—the most popular of whom was called El Santo—did battle with zombies, robots, mummies, and evil scientists in schlock-horror films whose rock-bottom production values made Ed Wood look like James Cameron. The U.S. versions, horrifically dubbed and translated (and in which El Santo was called Samson), were even worse and have come to be fetishized by aficionados, one of whom publishes a zine, Santo Street, devoted to the genre. My wife’s mad at me; I passed out on the couch watching Mexican wrestling pictures on the USA Network again.

Milius, John. Hyperbolically martial screenwriter-director and iconoclastic Hollywood far-righty; the most raging and bullish member of the ScorseseCoppola-Spielberg-etc. generation. Deemed unfit for military service in Vietnam on account of his asthma, Milius channeled his virility and bloodlust into writing or co-writing the first two Dirty Harry movies, Apocalypse Now, Conan the Barbarian, and Red Dawn, the latter two of which he also directed. Per Snob lore, Milius was the inspiration for John Goodman’s Nam-obsessed character in the Coen brothers’ The Big Lebowski.

Mondo Cane. Nominal documentary that prefigured the Fox Network-style “shockumentary” by some decades. Made in 1962 by two Italian filmmakers, Mondo Cane became a midnight-movie staple by placing pseudo-serious commentary over disturbing pseudo-anthropological footage of rich and poor societies (e.g., grotesque California housewives burying their dogs at a pet cemetery, Chinese eating dogs) and scenes of National Geographic-style frontal nudity. In the pre-video age, the word mondo (which means, simply, “world”) came to signify cinematic transgression, as evidenced by the rash of crapola imitators {Mondo Bizarro, Mondo Teeno, etc.) it inspired.

M.O.S. In-joke filmmaking term, written on a slate or in a screenplay to denote a scene filmed without audio. The etymology is a subject of hot debate, some saying the abbreviation stands for “mute on sound” or “mike offstage,” but most taking the prevailing Snob line that the term originated with such transplanted Austrian directors as Erich von Stroheim and Josef von Sternberg, who would call for scenes to be shot “mit out sound.”

Movieness. Stock hack-crit term used, like a more fun version of postmodern, to denote a director’s or viewer’s hyperawareness of filmic conventions and techniques. Watching Kill Bill’.v gory, kinetic fight scenes, you can sense Tarantino exulting in the sheer movieness of moviemaking.

Murch, Walter. Exacting, innovative sound designer who was cultivated by Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas early in their careers; for Snobs, the genius of film sound. An eccentric, intelligent polymath, Murch dabbles in the other aspects of filmmaking—he co-wrote the screenplay to Lucas’s THX 1138 and edited The English Patient and Cold Mountain—as well as beekeeping. I’m not easily impressed, but Murch’s work on the opening sequence of Apocalypse Now was next-level shit.

Schrader, Paul. Whiz screenwriter and occasional director beloved by Snobs for his facility with brutal, sordid subject matter. Raised in a severe Calvinist household in Michigan—he never even saw a film until he was 18 years old—Schrader first emerged in the early 70s as a heavy-duty film critic and PAULINE KAI i protege before selling his screenplay for The Yakuza (1975), a story about an American (Robert Mitchum) who gets mixed up with the Japanese Mob. Since, he has written Martin Scorsese’s two most inflammatory films {Taxi Driver, The Last Temptation of Christ) and directed a sequence of fraught, atmospheric dramas redolent of crime, scuzz, and sexual perversion, including Hardcore, American Gigolo, The Comfort of Strangers, and Auto Focus— as well as the uncharacteristic Michael J. Fox mullet-musical Light of Day. His little-seen 1985 film, Mishima, about the great Japanese novelist who committed suicide, is a Snob cause celebre.

ShoWest. Trade convention put on in Las Vegas every March by the National Association of Theater Owners; renowned for being the first place that the major studios show trailers for their upcoming features, and, therefore, for being much less of an endurance test than Sundance. Dude, the new John Woo got tons of buzz at ShoWest; were so there on opening day.

Suzuki, Seijun. Japanese B-picture director of the 1960s whose violent Cinemascope action pictures grew increasingly eccentric as time went on, culminating in 1967’s Branded to Kill, about a yakuza hit man with a fetish for sniffing freshly steamed rice. Fired by his studio, Nikkatsu, for making “incomprehensible films” (a not entirely unfair charge), Suzuki spent years in the wilderness before being lionized by his burgeoning Snob constituency (which includes Quentin Tarantino and Jim Jarmusch); Branded to Kill has received the RITERION COLLECTION treatment, and in 2001, Suzuki finally managed to shoot its sequel, whose title, Pistol Opera, aptly encapsulates the outlook of violence-loving Asian-cinema enthusiasts.

Two-reeler. A comic film short from Hollywood’s “Golden Age.” (Most shorts ran about 20 minutes, or about two reels’ worth of celluloid.) Though virtually all the great early film comics performed in two-reelers, the Snob generally uses the term to denote the low-humor slapstick shorts churned out in the 1930s and 40s by such acts as the Three Stooges and, even more credenhancingly, the forgotten two-reeler stalwarts Leon Errol and Edgar Kennedy. Damon and Kinnear perform with the slapstick aplomb of an old two-reeler team.

Vidor, King. Sentimentalist American director of the 1920s-40s whose maudlin, often messagey films (especially the Depression-era homage to communal farming, Our Daily Bread) have been hailed by Snobs as masterpieces on account of their authentically audacious camera technique and technological innovation. Frequently confused by novice Snobs with the Hungarian-born director Charles Vidor {Gilda), who was no relation.

Zahn, Steve. Smallish, affable actor of regular-guy mien, exalted in Snob circles for his comedic performances in underperforming movies that only Snobs “got,” such as Safe Men (1998), Chain of Fools (2000), and Saving Silverman (2001). Usually matched with a similarly game young actor in a “buddy” scenario. Sam Rockwell was awesome in Safe Men, but I was really groovin’ on the Zahn!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now