Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

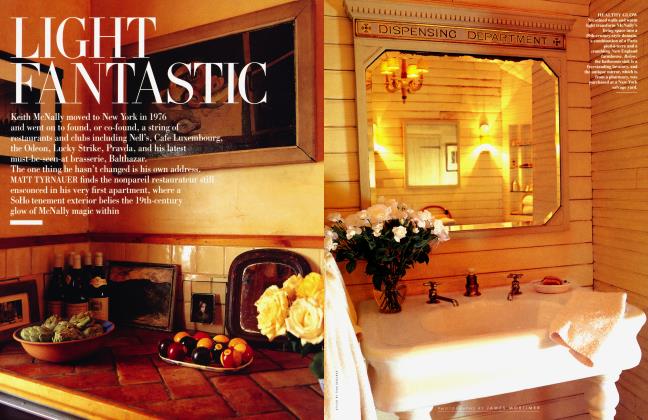

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMODERN LIVING April 2000

In L.A.'s Los Feliz hills, screenwriter Mitch Glazer and actress Kelly Lynch found their dream house, John Lautner's forgotten California modernist classic known as the Harvey Aluminum House. Against all commonsense advice—and after almost losing the place to Leonardo DiCaprio—they spent 13 grueling months searching for 50s-era fixtures and undoing the damage of time, weather, and previous owners. TODD EBERLE captured the striking results, while MATT TYRNAUER reported on how an architectural landmark was brought back to life

MATT TYRNAUER

"We treated the house as a piece of SCULPTURE, because Lautner designed houses as works of art."

It was a Sunday in 1998. The screenwriter Mitch Glazer, whose credits include Great Expectations, starring Gwyneth Paltrow, and Serooged, starring Bill Murray, was ritually thumbing through the Los Angeles Times real-estate section. "Every week Mitch would flip through the paper, and after every page I'd hear him say, 'Garbage.' Next page, 'Garbage. Garbage,' " recalls actress Kelly Lynch, who has been married to Glazer since 1992 and has been his companion since 1989, the year of her breakthrough performance as a strung-out junkie in Drugstore Cowboy. She is currently preparing for a role in the movie version of Charlie's Angels, and Glazer is finishing a production rewrite of the script. "Then, finally, one day—after almost 10 years, I'll never forget it—Mitch came across a small ad that made him stop," says Lynch. It read:

Bit by John Lautner, 1950. Gated + pvt. flat promontory w/300 deg vus, impressive circ entr to grand LR, lg kit, fam/ofc w/blt-ins.

A few hours later, Lynch and Glazer were in his black 1969 Pontiac GTO, traveling up a steep and narrow street in the Los Leliz section of Los Angeles—an old movie-star enclave dotted with Spanish haciendas and modern pavilions near the entrance to Griffith Park. "We were anxious to see this place," Glazer says, "but our expectations were not high, because we had been looking for years for the right kind of midcentury house in L.A. and we hadn't found it."

As soon as the couple started up the long concrete driveway, Glazer says, "we both gasped." They were looking at the massive, gracefully curved roofline and tall windows of the Harvey Aluminum House, a bold, circular structure built of wood and concrete, the work of one of California's great practitioners, John Lautner.

The Harvey Aluminum House—it's always called that—got its name from the man who commissioned it, Leo Harvey, an industrialist and real-estate tycoon who was the founder of Harvey Aluminum Corporation and, according to the contractors who originally built the house, styled himself as the "pop-top king" of the United States. He had, according to Glazer, something of "a Reynolds [Aluminum] complex," and needed an impressive house to compensate for it.

Glazer and Lynch knew at once that they had stumbled on a very rare thing: a forgotten, though unfortunately neglected, modern masterpiece in the Los Angeles hills. "I had never before seen anything like this building," Glazer says. "The places where the metal, stone, and glass meet in the structure were incredible to me. I loved the machine-age quality of the materials and the wonderful way the house engaged the landscape—and also, from certain angles, seemed to even hover above it."

"The places where the METAL, STONE, and

GLASS meet were incredible to me," says Glazer.

"This house was obviously built for—and by—a man who wanted to be in TOTAL COMMAND."

It was like tripping over Sleeping Beauty," says Lynch. "We had no doubt about what it was. But almost everyone who saw it—including our broker—didn't think it could be brought back to life." By the time Glazer and Lynch walked to the rear of the 1.3-acre property and saw the panoramic view—with the Griffith Park Observatory on one side and the HOLLYWOOD sign on the other, and stretching to downtown L. A., the Pacific Ocean, and Santa Monica—"we were vibrating," says Glazer. "I knew it was meant to be. It needed us and we needed it. We are both very good at looking at a place and seeing what it was or what it could be again. Our only fear was that some movie star would come along and buy the property for the view and either tear the building down or make it into Swingpad 2000—you could easily go that direction with this house."

Their fear proved legitimate. A month after they submitted a bid, they were informed that they had a rival—"a Hollywood big shot with deep pockets."

When they found out it was Leonardo DiCaprio, Lynch burst into tears. To make matters worse, it was Leo post-Titanic. This was more than likely going to be his King of the World house.

"I had already begun making lists of what I needed for the restoration," Lynch says. "I had it worked out in my head." It was a dark few days, but DiCaprio eventually dropped out and later bought a house in the Hollywood Hills that had once belonged to Madonna.

As soon as escrow closed, a grueling 13-month restoration project began. "The house was in overwhelmingly bad shape," says Glazer.

The pink Arizona-flagstone walls were caked with dirt, the mahogany parquet floor in the living room was rotted, the satinwood and padauk and bleached-mahogany walls were discolored by seepage stains, the green and pink marble fireplaces were almost black, and the custom aluminum fittings made specially for the house by the Harvey company were pitted and blackened. A wrongheaded 70s addition had to be torn down; the moldering lap pool needed to be replaced; the massive round roof had to be refinished in copper. "All of Lautner's modernist intentions had been thwarted over the years," says Glazer. "It was a house that was way ahead of its time technologically and formally, and the previous owners had tried to 'normalize' it," with disastrous results. Even the spectacular glass-enclosed round forecourt of the house, with its crystal starburst chandeliers and ceiling that looks like the turbofan of a jet engine, had been chopped up with drywall.

"I literally took a year off as an actor and made this restoration my job," says Lynch. "I would be at Home Depot 10 times a day or going around to weird electronic stores and asking for obsolete fixtures. I'd say, 1 need dicky light switches, the kind from the 50s.' They'd say, 'Those aren't made anymore.' I'd say, 'Find them.' Eventually they did. It was like restoring a work of art, unraveling a mystery and being on an archaeology dig."

Besides acting and writing and our daughter, Shane, architecture is the most important thing in our lives," Lynch says as she and Glazer take in the view from their living room, which looks out over Hollywood. Lynch is still in her workout gear, fresh from martialarts practice for her Charlie's Angels part. Glazer is wearing the screenwriter's uniform: a plaid shirt and blue jeans. Shane, 14, is in her bedroom doing homework. It is sunset. In the distance, jumbo jets glide toward Los Angeles International Airport. A localnews helicopter zips by in the foreground. Like the aircraft, the Harvey Aluminum House seems to levitate above the L.A. basin. When it was newly built, neighborhood kids used to refer to it as "the flyingsaucer house" because of its dramatic, round roof, which is 100 feet in diameter. "There is a kind of welcome-to-the-future feeling in this house," says Glazer as he throws a switch which raises two wall panels to reveal a wet bar and an elaborate stainless-steel soda fountain.

"This house puts on a show for you," says Lynch. "People walk in and just lose their minds. When Anjelica Huston came here for the first time, she said, 'This is the house my father would have loved to live in.' What she meant was that it is unfussy. It's a manly house. It has big broad windows and mahogany paneling. John Lautner was apparently very manly—a Gary Cooper figure. Women were very attracted to him, and this house was obviously built for—and by—a man who wanted to be in total command."

Lautner, who died at 83 in 1994, was a star pupil of Lrank Lloyd Wright's, and though he is an important figure in the history of modernism, his reputation has faded in the past several decades, while the reputation of his rival, Richard Neutra, has risen to lofty heights. Among architecture aficionados, there seem to be two camps: Neutra people, who like the elegant boxy look (Gucci's Tom Lord and Newport Beach financial executive Brent Harris are among them), and Lautner people, who go in for organic curves and, in some of the houses, Jet-sons-like gadgetry (German publisher Benedikt Taschen and Bob and Dolores Hope).

As it turns out, Glazer and Lynch are among the very few who can claim real devotion to both men. In 1991 they purchased and restored Neutra's 1959 Oyler House, a small gem set among 95-foot-tall rock formations in Lone Pine, California, near Mount Whitney. "The work on that property is what primed us for the much more complex undertaking of renewing the Harvey Aluminum House," says Glazer, who notes that the Neutra structure was "preserved by the desert air," while the Lautner house had suffered from L.A.'s rainy seasons, especially that caused by El Nino in 1997.

Often mistaken for a "period architect" or a playful futurist, Lautner could very well be the most famous unknown architect in the world. He made a big impression on Hollywood art directors, and they have done much to keep his aesthetic alive. His Elrod House (1968 ) is featured in Guy Hamilton's Diamonds Are Forever, the iconic Chemosphere (1961) is the star of Brian De Palma's Body Double, the rainbow-shaped Garcia House (1962) is the villain's home in Richard Donner's Lethal Weapon 2. At first glance these structures look like fugitives from Tomorrowland. Upon closer inspection, they reveal themselves to be works of profound sensitivity and extraordinary craftsmanship, with a progressive, Utopian edge. They are the work of a serious idealist, whom Wright called "the second-best architect in the world."

"We treated the house as a large piece of sculpture, because Lautner designed houses as works of art," says Lynch, pointing to construction details in the round forecourt, or "lobby," as they jokingly refer to the 2,800-square-foot room, which is almost devoid of objects except for a grouping of six pieces of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe furniture. "We want your eye to keep moving in this house."

That is why the couple has furnished the seven major rooms so sparingly. "It's a Zen palace," Lynch continues. "We could fill it with furniture, but we won't... because this whole trip is really about honoring John Lautner." Given the rich materials Lautner used for the house (it cost a steep $2 million to build) and the exquisite built-in vitrines, credenzas, and cabinets, non-Lautner furniture seems irrelevant in the space anyway. The cantilevered desk and golden padauk walls in Glazer's study—originally Harvey's home office—are fit for a modern captain of industry. "Someone who clearly wanted to feel like he was on top of the world," says Lynch. Glazer calls the room "the Howard Roark" office, a reference to the architect hero of Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead.

Lynch and Glazer have done everything they could to bring the house back to its original condition. Lor the black-and-green marble bathroom off of the office, which was built to Harvey's specifications, they tracked down the exact yellow linoleum that Lautner used for the ceiling. Lynch supervised the stripping and replating of every vintage Kurt Versen bullet lamp in the house. Even the diffusing rings for the recessed lights—which mimic the support structure for the circular core of the building—were meticulously restored. In cases where Lautner-approved elements could not be documented, Lynch and Glazer improvised. "I went to the Beverly Hills Hotel to get the proper nonoffensive pink for the outside walls," says Lynch, holding up a chip of the hotel's plaster. "Pink is difficult. You don't want it too fleshy or too bubblegum-y, and I always thought the Beverly Hills Hotel got it right."

One rare change from Lautner's plan was made at Lynch's insistence: she had a large picture window cut into her bathroom wall, transforming what had been a grim pink marble tomb into a shimmering glass cube. Now all of downtown L.A. is visible from the tiny room. "This is the best seat in the house—no offense, but look where I'm sitting," says Lynch, positioning herself atop the vintage 50s toilet. "There's no doubt about it, great architecture improves your life."

Just then Glazer walks into the room, and the sky above Los Angeles starts to turn a fiery red. Lrom the Harvey Aluminum House, the city's skyscrapers look like an MGM Emerald City backdrop. "This house elevates you," says Glazer. "Every night we feel peaceful here, and every morning we leave with a spring in our step. The house is simply empowering."

Mitch Glazer and Kelly Lynch still live in John Lautner's Harvey Aluminum House.

"THIS HOUSE ON A SHOW FOR YOU. People walk in and just lose their minds."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now